‘Mundian To Bach Ke’ was first released to limited fanfare in 1998 by a young British-Indian producer and DJ based in Coventry, who called himself Panjabi MC and liked to mix bhangra songs with hip-hop.

It has a shrieking single-string melody to start off—that infectious ting-titing-titing-titing tune that carves itself into the brain. The singer Labh Janjua then launches into the high-pitched vocals that transport the listener from the club to the pind, the Punjabi countryside. He’s warning young women to beware of the boys—mundian to bach ke rahi. An ecstatic dhol rhythm joins the party. So does a sample of the bouncy bass-line from the opening theme of Knight Rider. [1]

At the time, it was so new and electric. In its early days, the track did the rounds of the underground bhangra scene in the UK. Gradually, it made its way to the club circuits in Italy, Turkey and Germany. As it picked up steam, the song was re-released in Germany in November 2002. It exploded soon after. In January 2003, it climbed to No. 5 on the UK Top 40; [2] Jay-Z rapped on a version that dropped in April 2003; it made it to the soundtrack of the oddball Hindi-English movie Boom. [3] It is estimated to have sold around 10 million copies, making it one of the highest-selling singles of all time.

The song is a timeless classic now, an evergreen banger. I’ve never been to a wedding party [4] where people haven’t gotten slightly deranged whenever it plays—and it plays, without fail, near the end [5] once everyone is sufficiently blitzed. All manner of DJs swear by it. Outside India, it’s come to symbolise the country in a sort of essential way that few pieces of popular culture have managed to do.

Much in its backstory remains unacknowledged and unheralded. There’s the player of that iconic tumbi line that makes the song instantly recognisable; the rights dispute that derailed the relationship between producer and publisher; the singer who was denied a visa to perform in the UK; the manner in which it touched young artists and music lovers, and changed trajectories for good.

Here’s a brief history of ‘Mundian To Bach Ke,’ from the point of view of those who made, lived, and experienced it.

Starring:

Panjabi MC: producer and writer

KS Bhamrah: singer and multi-instrumentalist

Ninder Johal DL: owner, Nachural Records

Amit Trivedi: music composer

Prabh Deep: Punjabi rapper and producer

Sonya Khanna: Delhi-based hip-hop and UK Punjabi music DJ

Anushree Majumdar: writer-editor; wrote master’s thesis on Islamic punk at Western University, Canada

Sankhayan Ghosh: film critic, Film Companion

Uday Bhatia: film critic, Mint Lounge

(Interviews have been edited for the sake of length and clarity.)

The Making

y the late 1990s, Birmingham in the West Midlands was a hub for bhangra music, a sound inextricably tied to the South Asian diaspora’s search for identity. Bhangra was a connection to the past in a Britain not entirely free from the spectre of Margaret “there’s no such thing as society” Thatcher.

The scene had fans in Indian diasporas around the world, particularly the US and Canada. Artists such as Bally Sagoo were all the rage. Sagoo’s version of the Punjabi folk song ‘Mera Laung Gawacha’ crystallised motherland nostalgia for a generation of British Asians.

The six-member Apna Sangeet was one of the great acts of this scene. They were a “superband,” as the cult arts newspaper The Stage described them in 1995, “virtually unknown to non-Asians.” By 1994, they’d already put out nine albums. Metropolitan audiences in India had started to take notice, helped along by cable channels like MTV and Channel V. But the one true crossover success hadn’t arrived yet.

That was about to change. Rajinder Rai aka Panjabi MC was a young producer in his twenties from neighbouring Coventry. In 1998, he released an album called Legalised which merged hip-hop and electronic elements with bhangra and traditional Punjabi singing. It did well on the UK Asian scene, but didn’t get any traction in the mainstream market.

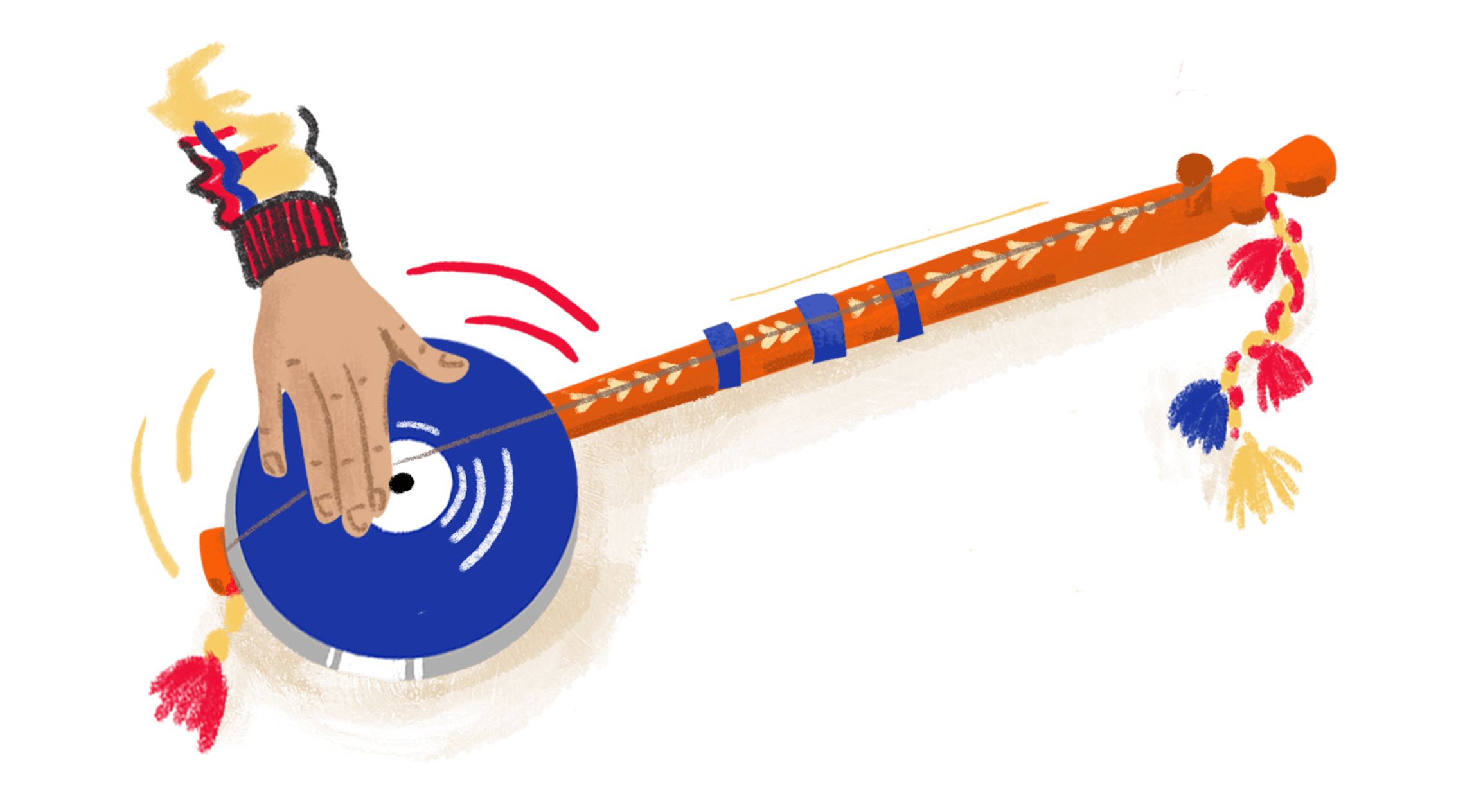

The album was released on Nachural Records, established by a former marketing consultant named Ninder Johal DL, who played tabla for a band he managed, called Achanak. Johal wanted to make bhangra go global. KS Bhamrah was a singer and multi-instrumentalist with Apna Sangeet. Legalised had a track that opened with Bhamrah playing a line on the tumbi, a single-string lute that may be a spiritual cousin of the iktara.

That track was ‘Mundian.’

Panjabi MC, writer and producer, ‘Mundian To Bach Ke Rahi’: My parents came to England from India, so there was obviously a lot of influence from there. In the house, we always spoke Punjabi; outside, it was only English. I used to listen to a lot of Punjabi music and watch Indian films.

When I first started music, I used to write raps; I was more an MC. At the time, I couldn’t really find any beats with Indian samples. And I couldn’t find any Indian producers who were doing hip-hop beats.

So I started sampling some music. I bought studio equipment, some samplers. I wanted to make, like, hip-hop beats with an Indian feel, you know? And I couldn’t find it. I mean, nobody was doing it. So I started producing the music myself. I sampled some desi music—old Muhammad Sadiq [6] songs, that kind of stuff.

“Labh Janjua was not so famous at that time. But when I heard his voice, it was 10 times better than anything I’d ever heard.”

Ninder Johal DL, owner, Nachural Records: I started Nachural in 1990. During that time, UK artists were fusing bhangra sounds with all other kinds of music. It was an exciting time. But we weren’t a global phenomenon. The problem was that we were only selling to people that looked like us—in mostly America, Canada, UK, India and Malaysia. They weren’t Portuguese, Greek, German, Italian. That was the market I was aiming for.

Panjabi MC came out of the blue and said, ‘I’d like to play you some stuff.’ He obviously had a really good talent. So I said, ‘Well, here’s some tracks. Can you remix them for me?’ He did, and they worked well. He wanted to do some stuff of his own. ‘Can I bring it back to you?’ And he came up with the concept of Legalised. [7]

KS Bhamrah, singer and multi-instrumentalist: In those days, in the 1990s, Panjabi MC used to come to me to get some samples, because I used to play the tumbi, the harmonium, the banjo, a couple of other instruments. [8] Before ‘Mundian,’ I worked on his album Souled Out, or something like that. [9] Around 1998, he came to me again and said he’d done a full album. So he wanted me to play tumbi for him.

Panjabi MC: I came to India to record, paying for the trips with my own money, with the likes of Kuldeep Manak, Surinder Shinda, Muhammad Sadiq, these legends of Punjabi music. I wanted to capture the original vibe of the singers. I didn’t want them to sing on a hip-hop beat, because I thought they might change their style then. [10] I was looking for traditional, old, desi-style singing. And Labh Janjua was not so famous at that time. But when I heard his voice, it was 10 times better than anything I’d ever heard. We ended up recording about 20 songs on my first session. His voice just fit in perfectly into the whole vibe I was doing. The vocals were recorded at Inderlok Studio [11] in Ludhiana. The tumbi player was KS Bhamrah, and the dhol player was Sunil Kalyan from London.

KS Bhamrah: He just brought the vocals and a simple beat to my studio, and asked me to play the tumbi on it. After that, he added some other rhythms and beats.

Top of the Pops

Panjabi MC left Nachural Records in 1999, but he continued to push the song in the underground club circuit. Meanwhile, Ninder Johal travelled far to spread the gospel of bhangra. Panjabi MC and Johal fell out over a dispute about the rights to the song. It’s something that ends up happening often in the music business, especially in the face of unexpected success. Later, there was a misunderstanding between Panjabi MC and Janjua. None of this got in the way of the rise and rise of ‘Mundian.’

Panjabi MC: I put the song on vinyls, and I sent it to many, many DJs. I was one of those DJs who was a “bhangra DJ,” but I used to play to non-bhangra people. I did a show with Tim Westwood, who was probably the biggest DJ in England at the time for hip-hop. And then we did a show in Leicester. It was quite crazy because this was the first time these DJs were playing an Indian song. And then we started getting on to compilations.

I got it distributed through one of the underground vinyl distribution guys. Some DJs got their hands on it. You know, in Berlin, Knight Rider, the actor who played the Knight Rider, David Hasselhoff, he’s German [12] —he’s quite big there, and so is the show. That’s why they recognised the song and sample more, I think.

Ninder Johal DL: It was difficult to convince the mainstream or non-Asians that this track, or any bhangra track, would work. I set on a journey of about 10 years, trying to persuade the mainstream music industry to take bhangra seriously.

Every year, I would go to these trade fairs, WOMEX and Midem. [13] At these places, everybody tries to explain to other companies what music they have, and would they like to licence it. I did this for about 10 years and nobody would licence the music. They said they don’t understand the melodies, they don’t understand the lyrics. I took all my CDs and went to Germany, France, Switzerland.

And I remember on the tenth trip to Midem, my wife said to me on the phone, ‘Listen, I think maybe you ought to give this dream a conclusion now. You’ve been at it; maybe you should go and do something else.’

Eventually, in 2001, I managed to convince a small Italian label [14] to sign the Nachural Records catalogue. They said we can’t give you any advances but we’ll give you royalties. Then, about six months later, I managed to convince a little Turkish label to sign the Nachural catalogue including Panjabi MC’s track. Now, this is where we struck lucky. The Turkish DJs also travelled a lot to Germany, and would play dance music in the German clubs. In 2002, I took a call in the summer from Universal in Germany, who said we want this track for Europe. [15] They said we don’t understand it, but everybody will be playing it.

Panjabi MC: Ninder was taking all the rights, all the money. I was young then. He wasn’t telling me that the song was a hit. I had paid him to clear the copyrights (of the samples used on Legalised), and when Tim Westwood and big DJs…like, in America, Fatman Scoop, all these big DJs of the time were playing it, I was telling Ninder that this song is going to the mainstream, so are you sure you cleared it?

When the labels [16] applied for the rights, Ninder said he doesn’t want me involved in the song anymore; that he’s going to do a deal with the label. And then they made this video for it in Malaysia, which I only saw when it was on TV! That’s when I went a bit crazy. I told the guys, ‘You wanna take the song, take it, it has nothing to do with me.’ The Americans, the Germans, they said, ‘Look, we can’t take the song without you, you know?’ That’s when Ninder finally turned around and said, ‘OK, you know what, we can go 50-50 on it.’ Finally, we sued him and got the rights (to ‘Mundian’) back after 20 years. [17] And it wasn’t easy, because he was adamant. It’s almost like I’d done something to him.

Ninder Johal DL: The sample that was used was owned by Universal Music, so we had to pay them for the publishing rights. If you use someone’s sample, you have to pay.

About the other thing, a dispute is a dispute; he’s got his side, I’ve got mine. My end of the story is quite simple: He left once we put out Legalised. He thought nothing of it, he found another label. Which is fine, he’s entitled to do that. And it was interesting that he only raised the issue of ownership once we started to chart.

But remember, it took a full five years after the first release for it to go mainstream. It became an issue in 2002, because I think maybe he thought, ‘Hold on, what’s happening here?’

He made music that became global, and I can’t take that away from him. He’s a talented guy, I’m not going to suggest otherwise. But we just have different perspectives of that time.

We managed to sign the song on to Sony in the UK. We started to get BBC Radio 1 airplay. We had nine number ones, including in Italy, where we knocked off Ronan Keating. In January 2003, I think around the 23rd, it went to number five in the UK. And then I went to Midem that weekend, and everybody wanted to sign the track. By 2004, we’d sold in every territory except China.

KS Bhamrah: One day, Panjabi MC came to me, he said, ‘Praaji—brother—congratulations! Our song is number five in the mainstream charts, in the UK Top Of The Pops.’ I said, ‘No, you’re joking!’

“As soon as the beat drop, we got the streets locked”

In April 2003, a remixed version of the song, called ‘Beware Of The Boys,’ or just ‘Beware,’ came out in the United States. It featured American rap superstar Jay-Z rapping on top of ‘Mundian.’

Prabh Deep, rapper: I was heavily into that scene when I was growing up—you know, Panjabi MC, Bally Sagoo, all those guys. I think that was the first Punjabi song I’d heard which had a western influence. See, back then I used to listen to fucked up Bollywood shit. Those sad songs, repetitive chords, repetitive lyrics. Then I figured the UK and US Punjabi scenes, and it personally changed my whole perspective. I moved on to Panjabi MC, Dr. Dre. And it wasn’t just ‘Mundian,’ he actually dropped a bunch of albums which are not mainstream; I’m talking about the fucking 1990s. And we bump that shit today as well.

Panjabi MC: When Jay-Z first came out with Big Pimpin, I thought this was one of the first songs where hip-hop was mixed with Indian music. [18] And I was like, ‘Has he heard my song?’ [19] I met him at a club, and he wanted to jump on the song, and obviously that was big news for me.

Ninder Johal DL: We signed one deal with an American company, [20] and then Jay-Z came on board. He approached the company in America and said he wanted to feature on this track, so we did a deal between Nachural and the American company, and we got on the American charts as well. Job done.

DJ Sonya, Delhi-based DJ: I played with Panjabi MC when I was first starting off, opening for him. I remember him telling me how he was inspired by underground hip-hop culture.

People who listened to Jay-Z got to know who Panjabi MC was. But in India, everybody already knew who he was. People didn’t expect Panjabi MC and Jay-Z to collaborate; it came out of nowhere. And you know, because Jay-Z did it, a lot of the Indian audiences got to know who Jay-Z was; it wasn’t just the other way around.

Till today, if you play at any expat party, or at a club outside India, ‘Mundian’ is still the most popular song ever! And the thing about it is, you can play it at any gig with any crowd, and it really doesn’t matter. I did a gig in Hyderabad for Ivanka Trump three years ago. [21] Sixty percent of the crowd was expats. I was mostly playing hip-hop but I wanted to play something for the Indians, so I played ‘Mundian.’ And not just the Indians…everyone, they all knew the song.

Anushree Majumdar, writer-editor: When I was studying pop music in Canada, in 2010, every single white person there knew this song. They didn’t care what the lyrics were. This was their introduction to Punjabi. Everyone knew it the way everyone knows ‘Tunak Tunak Tun’ [22] now. And the thing is, the song had travelled to them not through social media but through nightclubs.

“It’s the combination of a high-end tumbi and the low-end bassline; when you combine the two together, that’s when you get chart success.”

Prabh Deep: We went to Chandigarh, I think it was probably 2019. My DJ was playing there, and I was like, ‘Play “Mundian,”’ and I dropped the fader down without thinking twice, and the whole crowd was singing it.

See, I don’t give a fuck about Bollywood. Like, personally, I’m good with everyone, but their music sucks. And I say that to their face. But there are a few people where respect is due. And PMC, this guy, he’s one of the guys I truly respect. That body of work when he was at his prime, like, it’s still banging.

Ninder Johal DL: I’ll tell you exactly why this track did well. The first reason people got into this was when the bass kicks in—the Knight Rider bass. But if you ask people today, 20 years later, they’ll hum you the tumbi sound. That was the real reason it blew up. Of course, ultimately from a human perspective, it’s the combination of a high-end tumbi and the low-end bassline; when you combine the two together, that’s when you get chart success. It was lethal and unique in the way it came together.

After the song charted at No. 5 in the UK, they were invited to perform at the iconic BBC show, Top of the Pops. Labh Janjua was supposed to fly down from India for it, but it didn’t quite work out.

Labh Janjua (1957-2015)

Labh Janjua died in Mumbai in 2015 at the age of 58. ‘Mundian’ was his breakout song—it established him as an exciting young voice that the industry sat up and took notice of. He went on to sing for a number of hit Hindi films. [23] The Punjabi track was already a component of the standard Bollywood album smorgasbord, but Janjua’s delivery felt unique and startling. He had the gift of being able to dominate a song at high register. In his voice lay imminent danger.

Panjabi MC: When the song went mainstream, all the big channels here and in America—Top Of The Pops, MTV in NY—they all wanted to take me and Labh Janjua around to tour. When we applied for his visa, I had sponsorship from the biggest record labels in the world. Labh Janjua, he went to the visa office in Delhi but he did not get a visa.

KS Bhamrah: Because Labh Janjua couldn’t come to England that time, Panjabi MC asked me to mime on the song. I was well-known in the UK and Europe with my band, so I said no. People won’t like it because it’s somebody else’s song. So he said, ‘OK, then you come with me and bring your tumbi along,’ and he asked someone else to mime. We performed on BBC. [24] It played all over the world.

Panjabi MC: In England, the national programmes were asking, ‘Where’s the singer?’ So we said the singer has not got a visa!

Uday Bhatia, journalist: Punjabi as a language has always been there in Bollywood, but it grew in the 1990s because of these Punjabi NRI films which did so well, like DDLJ, Kuch Kuch Hota Hai, so they’d have two or three Punjabi-lyric songs.

Labh Janjua’s was a slightly different Punjabi voice. I mean, we were used to Mika and Daler Mehndi but this was a kind of raw folk voice that stood out.

You know it’s him, like, three seconds into any song he’s singing. I think it might have opened up Bollywood to all kinds of Punjabi sounds. Not only the more slick-sounding stuff like Daler used to do, but slightly more pind-sounding stuff. You can place him in the village, the pind, you can hear it.

Amit Trivedi, music composer, texting me: ‘Mundian’ was one of those songs which became an international sensation, and he was a global star. It was an honour to collaborate with him. I worked with him for films like Dev D, Luv Shuv Tey Chicken Khurana, Queen. He had a very rustic and desi Punjabi texture to his voice, of which I was a huge fan.

Panjabi MC: Labh Janjua was a very straight-up person, very humble. Like myself, just straight to the point, yeah? And the thing is, we were good friends for a few years, because I used to go to India every year and I used to record with him.

After he didn’t get his visa, he was so angry with me. A lot of people back in India were probably telling him stuff that wasn’t true when the song went mainstream. I don’t know what he felt. At the end of the day, I sent him a lot of money. I obviously paid him for the original recording. Then when the song went big, I sent him more money from the sponsorship. He had an amazing voice. And I’m so happy for everything he went on to achieve.

Ninder Johal DL: The high-end and the low-end—he was the thing in the middle that tightened it all together.

Anushree Majumdar: One of the joys of the song is obviously the singing. The voice modulation; the song starts off at a really high pitch, and if you just listen to the vocals, it’s a ridiculously hard song. And this is something that a lot of Punjabi singers can do—one of the reasons why Sukhwinder Singh [25] got so big at one point was his ability to ride octaves effortlessly, seamlessly.

Janjua doesn’t have Sukhwinder’s full-throatedness. Instead, he has this robust energy. For me, he took a song that is fairly sexist in its lyrics, at the same time acknowledging its sexism within the lyrics, and he made it fun for everyone. I don’t know him, but I want to listen to what he’s telling me. There’s a charming intimacy in his voice.

Amit Trivedi: He was a lovely human being and a very easy person to work with, very cooperative and sharp. I wish he was with us, I would have been still working with him a lot. I miss him.

Ticket to Bollywood

‘Mundian’ was on the soundtrack of Boom (2003) directed by Kaizad Gustad. It starred Amitabh Bachchan and was Katrina Kaif’s debut. More recently, an authorised remake called ‘Mundiyan Song,’ a pallid half-hit, appeared on the soundtrack of Baaghi 2 (2018).

Panjabi MC: I went to India when Boom released. I came down to do some shows, and we had a deal with a label, I think Sony. That’s when I saw the reaction it had had from around the world. And I saw all these other artists who were kind of leaning on this song.

Ninder Johal DL: In 2003, Sony India came and they signed it for the Indian territories. What was interesting is that in all those years, no one (major labels everywhere) would listen to me when I would give them the track. But now suddenly everybody was interested. Those Italian and Turkish companies that took it on first were absolutely tiny. The Italian one, CNI, may not even be around now—I mean, they were really small, one- or two-man outfits.

“For me, the song is all about identity. It’s all these guys from the UK, first-gen or second-gen immigrants, looking to meld their two realities.”

Sankhayan Ghosh, journalist: The song is so catchy, it gets stuck in your system. And your memories tend to be audio-visual. I’m the kind of Bollywood music buff who has found a lot of music because it became part of a film. For me—unfortunately maybe—my association will always be that clip from Boom, with Katrina Kaif in a bikini and Gulshan Grover. It’s an infamous scene from the film. [26]

It was a slightly more international and snazzy sound, decidedly different from the sound of the 1990s. There was the Monsoon Wedding song which had a similar style of singing, ‘Ajj Mera Jee Karda.’ [27] People like Jay Sean [28] would do one or two tracks in a film. Bollywood albums have this kind of thali system, you know, where you have everything: the dance track, the sad song, the shaadi number, and so on. It was part of the assortment.

Anushree Majumdar: I wouldn’t call ‘Mundian’ an Indian song at all. It’s a British-Asian song. It is very tempting to want to appropriate stuff like this. There’s this whole ‘Oh, I could have done that.’ But did you? Did you think of doing it?

Panjabi MC had the audacity to put Knight Rider on this song telling women, ‘Yaar, thoda bach ke.’ It feels like all of these references were boiling to a point up to ‘Mundian.’ For me, the song is all about identity. It’s all these guys from the UK, first-gen or second-gen immigrants, looking for a way to make their two realities meld.

The reason why this stuff doesn’t have an impact on Bollywood is because Bollywood is not about identity. Bollywood is about a song having a mood: Ye gaane ka mood kya hai? [29] What happened before this song? What happens after it ends?

Uday Bhatia: I’m not exactly sure this song was a huge deal for Bollywood. The correct parallel for this, in my mind, would be how Bollywood just picks up stuff that’s popular in the pop world and makes songs out of them. ‘Angreji Weed’ was one of Yo Yo Honey Singh’s first hits. That became a hit in the film Cocktail. They barely changed it, but they took out “weed” and made it “beat.” It happens now, when a Punjabi pop hit becomes so big that they just take it out and they tweak it. That’s probably a reliable strategy now but it wasn’t back then.

Fame and Beyond

DJ Sonya: I used to be a resident DJ when I started, 13 years ago. There was a place in Noida, which was like a pre-party place before people used to head to Elevate. Elevate [30] was the thing back then, so people would come here first to drink.

And because this was one of the biggest hits in UK Punjabi music, that opened the door to a lot of people like Jay Sean, Juggy D, Rishi Rich. Listen to their music: you take out the Punjabi lyrics or sample—maybe a dhol—and you wouldn’t be able to tell if it’s Punjabi music or hip-hop. That’s why it’s popular more now: people want to listen to hip-hop now that it’s back after the whole EDM thing. [31] But the Punjabi part makes it more familiar to Indian crowds.

When Social [32] opened in Chandigarh, they didn’t play regional or Indian music. But they started doing Wednesday nights with me, and the theme would always be UK Punjabi music, Punjabi rap and hip-hop. It became a thing in Chandigarh, and soon everybody else started doing it too.

KS Bhamrah: I’m a singer myself, but after ‘Mundian’ went mainstream, a lot of other producers asked me to perform the tumbi. You can play only three or four notes on it, maximum.

I performed with PMC in Italy. And after that, because he was so well-known, people would call me because he couldn’t go as he was so busy.

I got a call from Istanbul in 2003. There was a promoter who asked me to bring Apna Sangeet over there. I said to him, ‘Look, this is not my song. It’s somebody else’s; I’m just playing tumbi on it.’ He said, don’t worry, you bring your band. Normally, I don’t play the tumbi on stage; it’s a very small instrument so it can be difficult to handle. But I took it and played it there. You can’t have any track like this; it’s been 20 years and it’s still going strong. You can’t have any party without this song! [33]

Panjabi MC: There were so many territories that it was going into. India, Germany, then America, then Mexico, Australia. It was huge in Russia. So what happened was, one minute it’s blowing up in one place, then a year later in another. One year I’m doing 20 shows in, like, Romania, the next year I’m doing 20 shows in Russia. For 15 years, I had to go to Russia every New Year’s Eve (to perform).

And you have these Holi parties. Not exactly like in India—these are events where they have the colour and everything, but they don’t know anything about it. But they have the festival, with Indian music and 15,000-20,000 kids, colour in the sky. I did, like, thousands and thousands of those throughout the world. I was doing too many, I never came home. Now you’re doing an interview with me about that song. It’s still going, you know.

Ninder Johal DL: It was like a domino effect. It just kept going, going, going. And the thing is, I wasn’t going into this blindly. There was an element of rationality. I’d seen it with my own eyes between 1997 and 2000. We played with Fatboy Slim, Tom Jones, Prodigy at festivals. I knew the way people received the sound live. The challenge always was, how do you translate that live sound on to the record? And ‘Mundian’ did that.

After ‘Mundian,’ we got the music of Achanak placed on a Microsoft Xbox video game, Project Gotham Racing 3. While playing the game, as you’re driving around, you can hear a track from my catalogue!

I remember when the deals started to come, I still thought: It’s looking good. But I didn’t think it’s going to blow up. The only time I started to think something could happen here was on a summer day in Central London in 2002. I turned around when I heard the music, and it was a car with the roof off. But for the first time, it wasn’t Asian people in the car dancing, it was young white people. [34]

KS Bhamrah: I worked with PMC after ‘Mundian’ a couple of times, but nothing recently. Because he takes too long to produce things! He’s a fantastic boy; he speaks more English than Punjabi. He’s cool and calm, very reserved. Always just thinking about the music. He respects me a lot, I’m older than him—I’m 65! But the one thing about him is that he never shows off, he was never too proud.

Panjabi MC: I think with the internet now, anybody who’s searching for Panjabi MC will obviously find this one song, but they do find my other music too. I know what you mean, it’s always kind of the same vibe. I have over 200 songs, but they always remember this one! I can’t argue with that or complain.

I mean, a lot of the kids now are into lo-fi music, and I’ve always done my music lo-fi anyway. I’ve always used my bedroom studio, and recorded my own vocals. And my process: I have my laptop, I have a song loaded up, and I wait for the right inspiration or something. I don’t rush it. But I’m not interested in promotions and all that, never have been. I enjoy what I do—it keeps me sane, it keeps me happy. That’s why I do it.

Akhil Sood is a music and culture writer from the badlands of New Delhi. His selected works are available at www.porterfolio.net/akhilsood. He tweets @akhilsoodsood