There is a unique kind of chair, made of Burma teak and cane mesh. It has a slightly tilted back, and its legs meet to form a V-shape at the apex. Popularly called the “Chandigarh Chair,” created in tandem with the city that shares its name, it is now a collector’s item, fetching several times its original amount in auctions.

Most know the creator of the Chandigarh Chair as Pierre Jeanneret, one of the city’s chief architects. But like the city itself, the furniture was a product of several minds. In this instance, one of the chair’s co-creators was Jeanneret’s long-time collaborator, Urmila Eulie Chowdhury. She was also one of India’s first qualified woman architects.

In 1951, Eulie, the name she used more often, was part of a team of young Indians involved with building the new capital city for Punjab. Eulie was 28 that year. With short exceptions, she was to live the rest of her life in the city she helped build.

She is fondly remembered within architecture circles, and by those who knew her. But she remains an obscure figure outside these groups, in the way that her male peers aren’t. In histories of Chandigarh, she sometimes appears as a footnote and sometimes not at all, as in an ongoing exhibition in New York’s Museum of Modern Art that makes no mention of her contributions while spotlighting the work of her peers. [1]

The Chandigarh Project

ulie was one of the founding members of a unique project, one that, even in India, is rarely remembered as the work of the Indians who helped its world-famous chief architects. One of several possible sites in east Punjab, a province divided after Partition, Chandigarh was on the sloping foothills of the Shivaliks. It was then made up of scattered villages, set amidst banyans, peepal trees and mango groves. The location seemed ideal: Christopher Rand, in an article about the new town for the New Yorker in 1955, titled it “the city on the tilting plain.”

The new city was to uphold the ideals of a new nation, one that was forward-looking and freed from the weight of old traditions, healing from the trauma of Partition. The initial moves to settle on Chandigarh, and then select an architect for it, came down to two committed civil servants: Parmeshwari Lal Varma, an engineer by training; and Prem Nath Thapar.

Their first choice was the American architect Albert Mayer, who’d worked on village redevelopment projects in Etawah, Uttar Pradesh, and was known to Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru, who took no small interest in the development of Chandigarh. But plans changed after Mayer’s colleague Matthew Nowicki died tragically in an air crash over Cairo in 1950.

Thapar and Varma then reached out to Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, a pair of British architects then engaged in building the Ibadan University campus in Nigeria. Working in tropical climates, they had learnt to take advantage of natural conditions like wind flow. They’d also come to prefer the use of reinforced concrete, a durable, change-resistant material, over wood. [2]

To lead the project Fry and Drew suggested the name of one of the most famous living architects of his time, a man who had worked on projects in Soviet Russia, helped rebuild France after the Second World War, co-designed the United Nations building and had some claim to being the most influential modernist architect in the world: Charles-Édouard Jeanneret, better known as Le Corbusier.

Corbusier and Pierre Jeanneret, who were cousins, had had their disagreements. But for Chandigarh, they came together in an amicable partnership with Drew and Fry, characterised by camaraderie and only occasional fractiousness. [3] Le Corbusier was “architectural adviser” and the other three, “senior architects.”

A young team of Indian architects came on board in the initial months, the government having made their involvement a prerequisite for the project. These young architects would become the torchbearers of “a school of Indian modernism,” as historian Vikramaditya Prakash called it. They included men such as Aditya Prakash, Manmohan Nath Sharma, Piloo Mody, Jeet Malhotra, Narinder Singh Lamba, J.S. Dethe, A.R. Prabhawalkar and Bhanu Pratap Mathur.

A young Balkrishna Doshi, who’d been an associate of Le Corbusier in Paris, was involved in the drawings that would soon bring the buildings of Chandigarh’s Capitol complex, and Corbusier’s dreams, to life. In 1954, led by the civil servant and writer M.S. Randhawa, the planners also devised a horticultural project, to put in place a unique tree cover that would meld with the city’s topography and environs. For India, for the sleepy villages on the slope of that hill in eastern Punjab, for the architects, and for Eulie Chowdhury, the only woman in this group, Chandigarh was a project that afforded new beginnings.

Home and Away

rmila Saksena was born on 4 October 1923 in Shahjahanpur, then in the United Provinces. She was the oldest of five sisters. Shanta Das, her mother, had grown up in Gwalior in the Central Provinces. Just the previous year, Eulie’s father Ramji Ram Saksena, a professor of economics at the University of Allahabad, had been one of two Indians who cleared the exams for the Imperial Customs service, part of the Imperial Civil Service.

It was the beginning of a life of travel, first to Calcutta and Delhi, and then across the world, where Saksena combined his role of trade commissioner with diplomacy. This was an especially significant role in the 1940s, when India’s emergence as an independent nation shaped a new era of international relations in a postcolonial world.

Eulie’s schools included St. Joseph’s in Karachi, and later, the prestigious Loreto Convent, Tara Hall in Shimla. In 1937, Ramji Saksena moved to Kobe, Japan, as India’s first trade commissioner, and took Shanta and his daughters with him. Kobe was where the Indian trading community had established itself in the early twentieth century. They had interests in silk textiles and raw cotton.

“Architecture was directly concerned with real problems and people. In painting, the artist had contact only with himself.”

In Kobe, the Saksena girls were enrolled at the Windsor House School, from where Eulie and Malti appeared for the Senior Cambridge examination. As a teenager, Eulie developed an interest in painting, which soon transformed into a fascination with architecture. Many years later, speaking to All India Radio in 1963, she remembered her friends showing her books that depicted the exciting new architecture that had sprung up in France, and in her own country, India.

She’d been born in the heyday of the Art Deco craze, which was giving way to the aesthetic we now know as mid-century modern. It was an era in which functionality was increasingly matched to aesthetics. Glass and steel were coming to be employed extensively in construction. The science of making buildings seemed captivating to Eulie. “Architecture,” she said in the radio interview, “was directly concerned with real problems and people. In painting, the artist had contact only with himself.”

In Australia, where her father moved next, Eulie enrolled in art school for a year, and then went to the University of Sydney for a degree in architecture. There, she earned distinctions in theoretical subjects like the history of sculpture and painting as well as practical ones like freehand drawing. Her sisters were equally talented in the arts. Malti, who studied at Sydney’s Conservatorium of Music, later went on to work as a journalist, becoming the Bombay-based Onlooker magazine’s correspondent in New York. [4]

Bina studied at Barnard College in New York and wrote plays and books that were later published by Calcutta’s Writers Workshop. Eulie’s two younger sisters were born while the family lived in Sydney. Nita Saksena, and the youngest sibling Rita, are now in their seventies. Nita is an accomplished artist, who has held public exhibitions of her paintings in Delhi.

The earliest photos I’ve seen of Eulie are from her time in Australia. In those grainy black and white photos, she is in her early twenties, appearing at society dos, and at her graduation, in Malti’s company. She is a slight, bespectacled figure with short wavy hair. She is already wearing the knee-length or long skirts that she later said were better suited to a life spent tramping over construction sites.

After her degree, Eulie came to a newly independent India to gain some training experience. She recalled in the 1963 AIR interview that she worked for the Military Engineering Service for some months. The Saksena family had by this time moved to Englewood, a suburb in Bergen County, New Jersey, just across the Hudson river from New York. They lived in a red-brick Georgian mansion on Walnut Street, a house built in 1907 that I’ve discovered is still standing.

When Eulie rejoined her family here, she began to study for a diploma in ceramics. She then went to work in the office of the architect and town planner, Robert J.L. Cadien, who was associated with school and low-cost housing projects in Englewood. The work was to hold her in good stead on the Chandigarh project. It was also around this time that she met an architect and construction engineer named Jugal Kishore Chowdhury.

JKC

ugal Kishore Chowdhury, often called “JKC,” was born in 1918, in Assam’s Goalpara district. He, too, came to architecture in an unusual way. His nephew Ranjit Chowdhury, now a retired professor of English based in Guwahati, told me that his uncle was fascinated by cricket as a schoolboy. It upset JKC’s father, who, after a family conference, dispatched him to the Dacca School for an Overseer’s course. [5]

The story goes that JKC ran away from Dacca and made his way to Bombay, where he found menial jobs and worked as a deckhand. He enrolled in evening classes at the JJ School of Art, which had begun offering a full five-year course in architecture in 1936. [6] When he returned to his home state of Assam, he impressed chief minister Gopinath Bordoloi, who arranged for him to travel to London on a scholarship for more specialised training.

The scholarship journey took him further afield, to southern United States. He spent three months working with the Tennessee State Planning Commission in Knoxville, before he came to the offices of the architect Antoine Raymond on Park Avenue in New York, and met Eulie.

JKC and Eulie married on 6 August 1949, in what local newspapers called the first big Hindu wedding in quite some time. The civil ceremony was officiated by a Bergen county judge, in the presence of a swami from the New York Ramakrishna Mission. Soon after, the newlyweds decided to return to India, a country that needed architects, but had no technical specifications or formal registrations for their young profession yet. (The Architects Act was passed only in 1972.) They were the perfect candidates for what Chandigarh was going to represent: familiar with modern methods because of their work abroad, but also possessing a keen sense of the local.

Jeanneret’s Protégés

he new state capital was planned in a meticulous grid, with residential sectors set amidst streets arranged in a vector-like hierarchy. Le Corbusier focused on the monumental buildings of the Capitol complex that would come to define the city and new India. But he was a visitor, spending not more than four months a year in the country. So the team of young architects gravitated around Pierre Jeanneret, who remained in Chandigarh.

The residential sectors, with their different housing categories, were mostly the preserve of Jeanneret, Fry and Drew. The senior architects came to rely on their young Indian assistants who, Fry wrote, threw themselves heart and soul into the project. Aditya Prakash, for instance, worked on housing projects with Drew and on Neelam theatre with Jeanneret; Manmohan Nath Sharma, who later became Chandigarh’s first chief architect, worked with Corbusier and Fry. [7]

Eulie came on board the Chandigarh project in September 1951, and JKC began working on a project to build a new campus for the Punjab Engineering College. [8] Eulie, Mathur and Malhotra, Jeanneret’s close associates, were charged with designing different housing types and the colleges that came up in Sector 14. They also supervised the High Court building, one of the crown jewels in the Capitol complex.

Eulie found herself awed and inspired by her senior colleagues, especially Jane Drew. In a tribute, Eulie described her as generous and “amazing in her capacity for work.” Drew and Fry were a fetching couple, Eulie wrote: “Max with his ready wit and Jane with her desire to shock.”

“The picnics usually involved long drives in Piloo Mody’s car, and the architects were accompanied by Mody’s fleet of dogs.”

They brought life and verve to a place that was then a cultural desert. To entertain themselves, the architects passed their evenings in long conversations over drinks. The writer Nayantara Sahgal wrote to me in an email that Eulie “loved her whisky no more than the others did.”

Roopinder Singh, Eulie’s friend and former editor at Chandigarh’s The Tribune, heard stories about the picnics that the senior and junior architects went on. “They usually involved long drives in Piloo Mody’s car,” Singh told me, recalling what Eulie had told him. “And the architects were accompanied by Mody’s fleet of dogs.”

Even the reserved Jeanneret came to enjoy the company of his younger colleagues, with whom he went on walks to the villages that abutted Chandigarh. The inspiration for some of the furniture he designed with Eulie, JKC, Malhotra and Prabhawalkar was derived from how locals imaginatively used readily available material such as bamboo, wood, and coir.

For Jeanneret, Eulie soon became indispensable, particularly because she had learnt French in school and served as his translator on many occasions. She assisted with his correspondence with officials and bureaucrats, especially in Delhi. Shivdatt Sharma, an architect who joined the team later, told me that Eulie often served as mediator in difficult situations, and intervened on occasions when her colleagues felt aggrieved over work-related issues.

On 7 October 1953, the capital she helped build was inaugurated by then president Rajendra Prasad. In 1954, Drew and Fry left India, though Jeanneret stayed back. He called his most proficient woman student “la petite Eulie,” an affectionate allusion to her slight build. Over the years, as she assumed leadership roles and became a devoted champion of several causes related to Chandigarh, she came to belie the nickname.

As her colleagues became trailblazing architects in their own right, Eulie helped fashion the cultural life of Chandigarh. It was a purpose that went beyond devising physical spaces. By the 1960s, as the former principal of the Chandigarh College of Architecture Rajnish Wattas described her, she was already the “Grande Dame of Indian architecture.”

Bricks in the Wall

n their collaborations, Eulie and Jeanneret developed houses across sectors, ranging from the detached residences of judges and senior officials to the apartments of middle- and lower-income groups. The sectors formed self-sufficient neighbourhoods, with schools, common markets, and community centres.

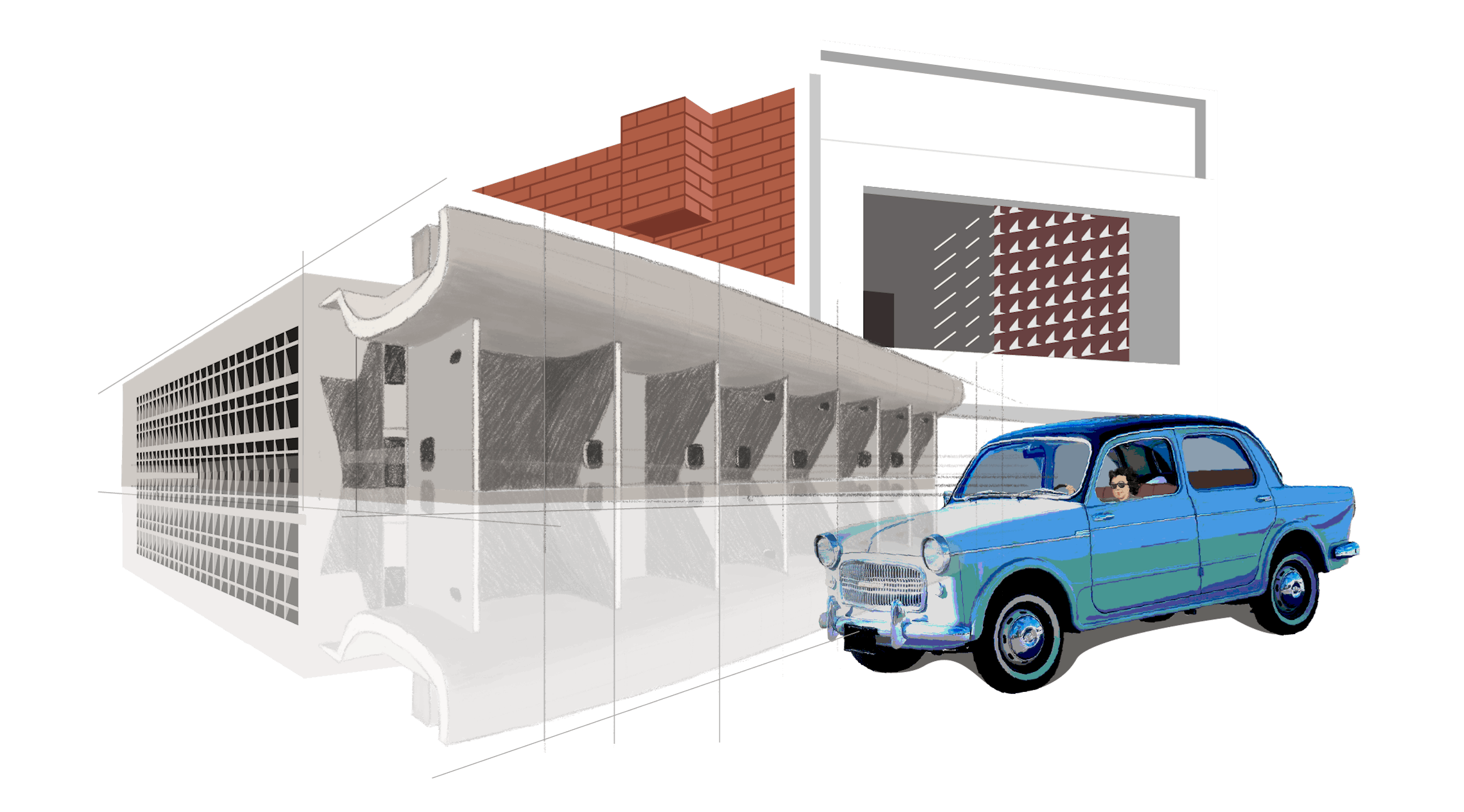

Corbusier preferred to work with reinforced concrete, but Jeanneret had a special liking for burnt brick, a material that was widely available locally. The architects used them as sun-breakers or “brise soleil”—to beat back the heat, and channel it during winter months. They also found varied design functions for the bricks: as wall patterns; as breaks in small windows or openings; as overhanging square boxes to create recessed windows for shade. The bricks were put to use in “shadow” walls and overhead canopies, too.

Eulie’s design inclination owed much to Jeanneret’s philosophies, the scholar Deepika Gandhi observed. “However, in the projects that she worked on there is evidence of further evolution—an exploration of plan, form, and detailing,” Gandhi wrote. “Her works are refined examples of modern architecture in their own right.” They show remarkable attention to detail, “and a sensitivity derived from her being an artist with an evolved personal aesthetic.” [9]

In her design projects, Eulie was concerned with moulding each building to its environment, fulfilling the needs of its users, and managing costs. She kept a tireless eye on air circulation and heat management. Living areas of larger spaces had their own enclosed verandas that faced northeast or northwest. Main rooms in low-cost houses had small openings that kept out the heat but allowed cross ventilation.

Architects who worked with her, like S.L. Kaushal and Sarbjit Bahga, pointed out that ventilation and privacy were abiding concerns for Eulie. Smaller houses had roof terraces designed with reinforced concrete, which helped manage the hot season but also allowed outdoor sleeping towards the evening. This design element was similar to that of traditional village homes, built with clay walls and straw roofs. Another feature of Eulie’s terraces was a brick screen with lattice work patterns, again to ensure both privacy and ventilation. [10]

To ease the visual monotony, the façade was developed imaginatively using exposed brick, lime-washed surfaces and stone. In some cases, as in Jeanneret’s own house in Sector 5, the square windows were used alone or in a “combination of two or four openings with a whitened concrete band around them.” Other houses used strategically placed vertical slit windows. The simple open staircase, set against the stone wall, also became a defining element: Eulie used it repeatedly in her later designs, including for the Government Women’s Polytechnic and for a hostel at the Home Science College.

“A Pace Exuding Efficiency”

t didn’t take long for Eulie to become a familiar figure in Chandigarh. Roopinder Singh and the lawyer and activist Manmohan Lal “Mac” Sarin recalled her driving around the city. She was barely visible as she sat behind the wheel of her blue Fiat. The joke as far back as the 1960s, Sarin remembered, was of Chandigarh’s streets having a “driverless car.” When she walked, her old friend Sharda Dutt wrote, it was never at anything but a “pace exuding efficiency.”

Eulie was to live in Chandigarh for most of her life, apart from a two-year stint as principal of the School of Planning and Architecture in Delhi. From 1970 to 1971, she was chief architect of Haryana; between 1971 and 1976, she was Chandigarh’s chief architect; and when she retired, it was at the end of an appointment as chief architect of the state of Punjab, from 1976 to 1981.

Eulie taught at Chandigarh’s College of Architecture, hopeful that her field would draw in more women, for whom she was a constant advocate.

During this time, she was involved in the second phase of Chandigarh’s development. Eulie designed the St. John’s School building, houses for deputy ministers, fire stations, cotton mills, schools and colleges. She supervised the Talwara township that housed workers and officers working on the Pong dam and the Bhakra-Nangal project. She also built the city centres of Amritsar and Mohali. [11]

She taught at Chandigarh’s College of Architecture, hopeful that her field would draw in more women, for whom she was a constant advocate. In the 1963 radio interview, she said that women were more suited to architecture than men. “Architecture requires creative ability and imagination as well as passion,” she said, “I have found many students choose this profession mostly as a means of earning a living whereas women choose it because they have a real interest in its creative aspect. Women are more conscientious in their work and, therefore, produce better results.”

Her own work ethic was by all accounts rigorous. Sarbjit Bahga has written of the time when he ran into her as she drove into a petrol pump. Ever the boss, she looked pointedly at her watch and reprimanded him for being late to office. [12]

Floors, Stages and Columns

s the 1970s wore on, Chandigarh, for all its meticulous planning, was hardly immune to the issues that marked major Indian cities: slums, squatter colonies, and transit settlements in which marginalised residents were squeezed. Eulie’s long years of residence in the city gave her a keen sense of its problems, both of the present and future.

She drafted a regional plan for Chandigarh, on the lines of the 1962 master plan for Delhi. Unless the region around the city—urban, industrial, and rural—was planned commensurately, she argued, the problems of Chandigarh would become unmanageable. [13] Her proposed scheme suggested the creation of new towns and villages around the region that would offer economic and social services, and therefore relieve the pressure on Chandigarh. She was agitated when construction by-laws were flouted, and kept meticulous records of all her city-related correspondence.

Chandigarh was also the heart of Eulie’s thriving social life. Much of it came to revolve around House Number 12, Sector 5, where she lived. Eulie was a fine hostess, neither obtrusive nor snobbish. Nayantara Sahgal told me that Eulie was never lonely. [14]

The house was plush and well-appointed, though Rajnish Wattas remembers seeing a Dettol bottle always at hand. Eulie never stinted on her smoking, and she used to say that the bottle helped hold the ash in.

Roopinder Singh recalled the space as simple, elegant and unusual. “The furniture stood out,” he told me, “and reflected in the shiny black flooring that had to be carefully maintained; something Eulie was meticulous about. It needed just the right amount of water, and never too much.” Wattas also recalled an uncommon design for the driveway, which took one right around to the back of the house.

Eulie was, among other things, involved in Chandigarh’s fledgling theatre scene, and helped set up the Chandigarh Amateur Dramatic Society, which produced and performed avant-garde plays. Her humour and sense of the quirky sprang to life on stage. Ranjit Chowdhury, her nephew-in-law, recalled how she helped stage The Bathroom Door, a one-act farce written by Gertrude Jennings. It was a send-up of class tensions in which various people speculate in front of a closed bathroom door. Mac Sarin and his wife, Niti, acted together in another production Eulie was involved in, Agatha Christie’s Murder on the Nile, staged in 1973.

Rehearsals were usually held in her house. Sharda Dutt writes of a bell Eulie devised to alert actors that the audience was expected to laugh at a particular juncture: they had to pause for a few seconds when it was rung. The young student in Japan who’d fallen in love with painting also returned to it later in life, and eventually showed her work at one or two exhibitions in the city.

Unless the region around Chandigarh—urban, industrial, and rural—was planned commensurately, Eulie argued, the problems of Chandigarh would become unmanageable.

One city institution, in particular, had a special place in Eulie’s heart. This was the Alliance Francaise de Chandigarh, which she was instrumental in setting up, and for whose gatherings she offered up her own home in the 1980s. For the Indian architects, the space was a reminder of their teachers, Corbusier and Jeanneret.

There was inevitably some complexity in her life, and this included her marriage with Jugal Kishore Chowdhury. He had little in common with his wife, despite their common profession. Friends who knew Eulie say they were incompatible, though they never formally separated. They had no children, and Ranjit Chowdhury suggested that this might have caused contention between them. Yet, Eulie was supportive of JKC in public. “She stood up for him,” Roopinder Singh told me, “especially when he was teased for his penchant for curved walls.”

In the early 1990s, Eulie started writing for The Tribune. The publication’s editors encouraged her to write on things that caught her eye for a weekly series called “Sinners and Winners.” Roopinder got to know her when he joined the paper in 1991. He told me he was intrigued by one of Eulie’s first pieces for the paper. Its title was “Why I Hate Children.”

Provenance

ometime in the mid-1980s, Eulie became involved with the Voluntary Euthanasia Society. She roped in some of the city’s eminences, as well as younger people like Mac Sarin, as members. Euthanasia was and remains a controversial subject in India, but the Society advocated that it was humane not to prolong human suffering. Piloo Mody, Eulie’s friend and colleague, had spoken up for voluntary euthanasia as a member of the Rajya Sabha. He had twice moved a private members’ bill, but it had found few takers. [15]

In mid-1995, Eulie was told by doctors that she only had a little time left, and she decided to return home. The Euthanasia Society’s belief, that it was vital to add life to one’s years rather than years to one’s life, may have influenced her decision. Eulie passed away on 20 September 1995, six days after coming home from the hospital. She was 71.

In 2009, House Number 12 in Sector 5 was demolished. This was nothing short of a tragedy, Roopinder Singh wrote later, [16] for Eulie had been a leading figure of the Save Chandigarh Movement. Mac Sarin told me that a “monstrosity” with high grey walls and security presence came up in its place. In 2017, Pierre Jeanneret’s house met the opposite fate. It was made a museum following the declaration of the Chandigarh Capitol project as a UNESCO Heritage Site.

he Chandigarh Chair is now a collector’s item. In a 2013 video installation titled Provenance, the American visual artist Amie Siegel documented its journey. Before the chairs began fetching record prices at international art auctions, they lay forgotten in warehouses: stacked one on top of the other and packed away in storage containers. When they became coveted objets d’art, their value was entirely attributed to the genius of Corbusier and Jeanneret. The woman who’d played a part, often a leading one, in creating them, had been all but forgotten.

This is of a piece with the forgetting of many unconventional women from the history of the arts, and the history of independent India: women who were brilliant, unapologetic, defiant, generous, hopeful. But it seems especially unfair that Eulie has disappeared from Chandigarh, to which she’d dedicated her life’s work—one that saw a new Indian city as a place that could be joyously liveable and modern.

Anuradha Kumar's nonfiction pieces have appeared in Scroll.in, thejuggernaut.com, The India Forum, and other places. She lives in New Jersey, and has degrees in history, management and creative writing. This is her first piece for fiftytwo.in.