“Dusre ko dekhte thhe choote usko, aur phir hum soche ki hum bhi choo le,” Chandmuni Kerketta said with a pause and a wide smile. “Lekin chue, toh kuch samajh nahin aaya.” I saw others touch it and I thought I should, too. But when I touched it, I didn’t understand anything.

A 24-year-old from Mandar block in Ranchi district, Chandmuni had started learning to use a computer in 2016. She set something in stone for herself: she was never going to choose a career that didn’t involve this machine. Ranchi, Jharkhand’s capital city, was only 30km away but still a world apart for Chandmuni, one of seven siblings in an Oraon tribal family. Her parents had already disallowed two daughters from working, but Chandmuni, who never left a task unfinished even on their 15-acre farm land, would find a way out. No one in the family had a non-farming job. The computer was her ticket.

When I visited Chandmuni’s ancestral home in Pungi, the evening glow lit up the faded blue walls of her room. Outside, a clothesline of pink and orange popped against trees made bright green by a recent drizzle. Smoke from a recently opened brick factory curled above the family’s cauliflower and watermelon field. Her desktop computer hummed on a low desk next to the bed.

In 2018, when she was still in college, Chandmuni was hired as housekeeping staff at an IT company called iMerit in Ranchi. She served tea and biscuits to those typing away. “Don’t turn it off when you leave,” she used to joke with the staff. “Go use the washroom na, let me use it now.”

“Sometimes, I really did get to touch it!” she recalled.

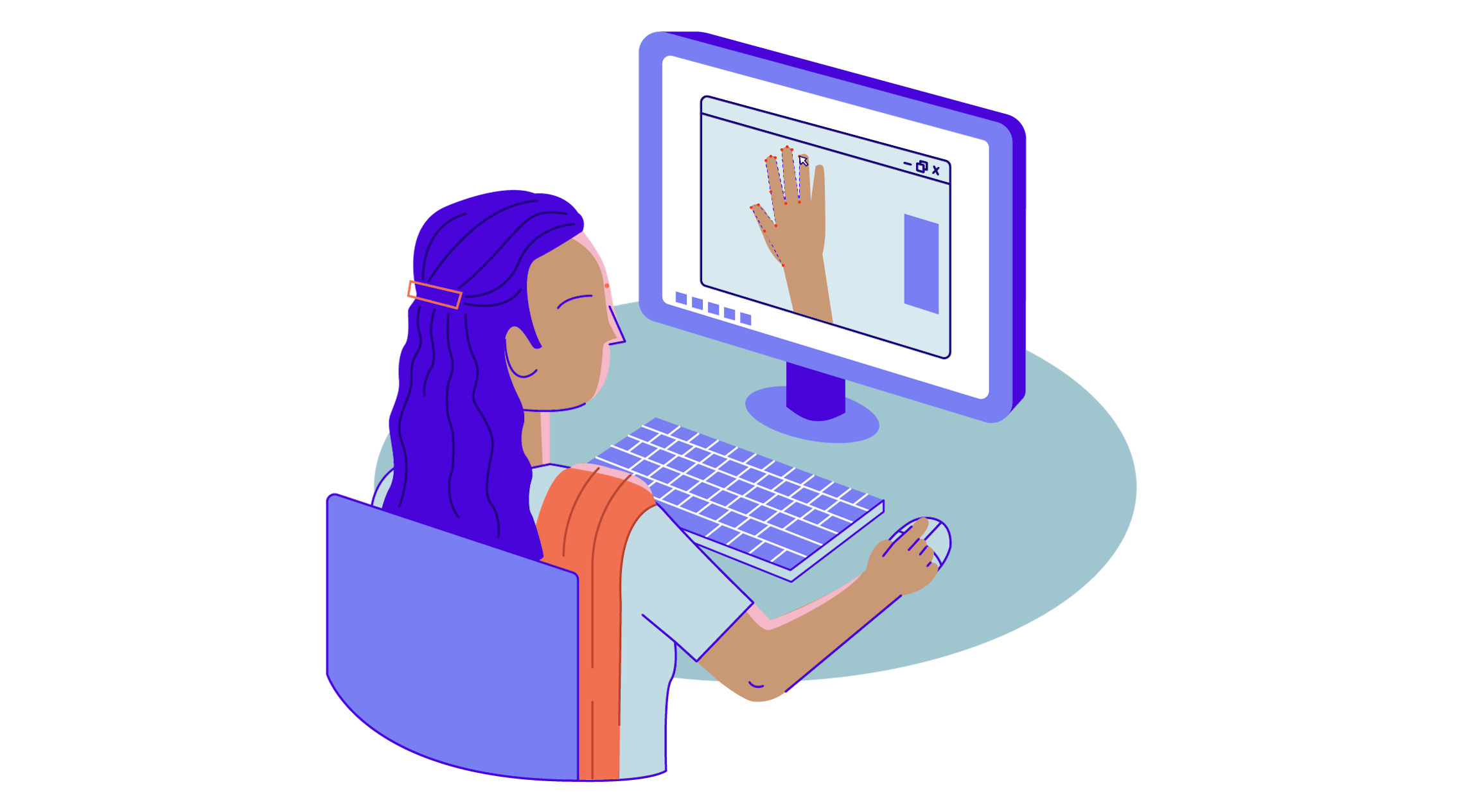

Within nine months, Chandmuni was a data operator at iMerit. When the company expanded into data annotation, Chandmuni started doing that, too. Now, from 6am to 2pm, she sits at the machine in her house. Her job is to mark the joints of a hand: 20 in a hand, four per finger. After the end of the work day, she focuses on housework and studying for a Master’s degree in history.

Her dotted images, along with a mass of others, funnel to a US-based company that uses the data to train its artificial intelligence models. When the algorithms are shown a hand, they will have enough past inputs to know what they are looking at. Eventually, they may be ready to conduct robotic surgeries.

Shifting the Centre

handmuni is among a growing number of women who are tasked with perhaps the most pressing, albeit unglamorous, work of the AI pipeline: data annotation, or labelling. Most of them are based in small towns and villages in India.

The “data problem” is central to machine learning architectures, which, in the last few years, have revolutionised AI. The more data you have—images, videos, text—and the more precisely it is labelled, the more sophisticated the algorithm is likely to be. In fact, you’re likely to have done some basic data labelling yourself: when Google’s CAPTCHA technology asks you to mark all the boxes in a grid that contain a traffic light, you are adding to the mass of labelled information. You can see how this would be useful for companies that are trying to build driverless cars.

India is one of the world’s largest markets for data annotation labour. As of 2021, there were roughly 70,000 people working in the field, which had a market size of an estimated $250 million, according to the IT industry body NASSCOM. Around 60 percent of the revenues came from the United States, while only 10 percent of the demand came from India. [1]

India is no stranger to back-end work for technology companies in the West. But unlike the call centre era of the 1990s, which was centred around cities like Gurgaon, Mumbai and Chennai, the labelling wave has moved away from the metro cities. Smaller cities and towns now have the digital infrastructure and literacy to host companies. Additionally, labelling images often doesn’t require proficiency in spoken English.

“India has a number of Tier II and III towns that have experienced mass urbanisation over the past three decades,” said Jai Natarajan, a vice president at iMerit, from his home near San Jose, California. “The second generation of those who came from the villages, they have had their faces pressed up to the window shop their whole lives. They are essentially urban, but not quite.” His company, now a decade old, has a strength of 5500, employing data annotators in India, Bhutan and the US. The company is even eyeing expansion to Ghana and Nigeria, according to Jai.

The NASSCOM report found that over 80 percent of data annotation employees are from rural, semi-rural and underserved backgrounds. Over 90 percent of the industry’s players are based in Tier II and Tier III cities—from Yemmiganur in Andhra Pradesh to Shillong in Meghalaya.

“But no one knows that these human processes are happening in the background. They don’t know the workforce is coming from our rural area. They just see the final application.”

CEOs, even those not focussed on “social impact,” told me that their companies employ a lot of women. “When we opened up our rural annotation centre in Jakranpalle village in Telangana, all the people who came forward were educated women,” Muzammil Hussain, founder of Tika Data, told me. “More than half had a Master’s degree. And they were housewives looking for work.” Tika Data’s other centre, in Hosur, Tamil Nadu, is staffed almost entirely by women.

I visited and spoke to workers in labelling companies in different parts of the country, travelling from Mannarkad, Kerala to Ranchi in Jharkhand. Most women I spoke to were uninterested in talking about how their task fit into the wider digital supply chain.

They sometimes drew on the phrase “artificial intelligence,” as they explained to me how their work of labelling images of roads, eyeballs, fruits, or sports games would help a computer drive a car, perform eye surgery, spot a rotten banana, or recognise a football foul. But in most instances, they steered our winding conversations back to how they had escaped past lives involving restrictive in-laws, abusive husbands and hospital bills; how a monthly salary of ₹10,000-15,000 meant the world to them. No one mentioned the words “algorithms” or “training sets,” but they were unequivocal about their newfound purchasing power and confidence.

At Infolks in Mannarkad, I watched as Silpa Subhash created a box around a motorcycle in a streetscape, and selected one of 20 categories on her screen to label it. The options included, among others: bicycle, handbag, aeroplane, gun, stroller, train. An hour into the workday, she had finished 100 out of 1000 objects she had been tasked with. Other projects, Subhash told me, required outlining objects or pinpointing specific areas. She said she was having “fun” at work.

“I don’t know what the work is about. Sir hasn’t told us. We just do the work,” said Sunita Kumari, who has worked in iMerit’s Ranchi office for nine years and now leads her own team. The 25-year-old is the primary breadwinner for her family of six and the most educated in her village, Lalganj. There are no other office-going women in Sunita’s family, as was the case with most women I met in the iMerit office. When Sunita was 17, she had been married into a family with an alcoholic father-in-law.

“I did think about the work’s purpose,” Sunita said. “But since they didn’t tell me, I stopped thinking about it.” Her colleague Chandmuni said she had never asked her bosses about what happens with the labelled data. “We do the work, we get money for it, so we don’t ask anything more.”

“At first, I thought this work was a back-end programme for gaming,” Sruthi M.K. told me. (We communicated through a translator, and a press relations associate from Infolks was present at our meeting.) When we met, she was on maternity leave, with not long left for her due date.

In 2018, Sruthi left Coimbatore and moved back to Mannarkad, her hometown, to work at Infolks. At the time, no one at the company had more than a rudimentary understanding of data annotation. Even the founder hadn’t connected the dots to automated systems in the US—but more on him later.

“One day,” Sruthi told me, “I realised this is not for gaming. We are teaching machines to see like a human. We teach a robot how to understand things on their own.”

Another Infolks employee, Megha Chandran, took a break from labelling the vessels in brain scans to describe to me how she explains her work to her family. “It’s like how, if you show a child the colour red enough times, they can recognise the category the next time they see the colour red.”

“But no one knows that these human processes are happening in the background,” Sruthi added. “And they don’t know that such a workforce is coming from our rural area. They just see the final application.”

Humans of AI

ruthi had described what is known in the field of AI as “humans in the loop.”

“Any major technology company in the last 10 years has been powered by a throng of people,” Jai Natarajan of iMerit said. “At some level, there’s denial. Investors like to hear that technology sells itself once you write the code. But that’s not really true.”

For several years, Big Tech headquartered in Silicon Valley has employed thousands of labellers around the world. In 2005, Amazon launched Mechanical Turk or MTurk, a crowd-work platform for on-demand tasks like labelling. Workers were paid by task. MTurk went a long way in popularising the gig model, especially among Indians, who formed a bulk of the user base.

As the desire for accuracy and security grew, companies began to look for third party firms that provided labelling as a service. Jesse Perez ran product operations at Facebook—now Meta—in California between 2016 and 2018. One of the workstreams he was in charge of was providing human-labelled data for machine learning applications. He remembered then chief technology officer Mike Schroepfer calling for the company to grow its data labelling capability by a hundred times. Without high-quality human-labelled data, Perez told me, building and tuning a model with all the bells and whistles would amount to nothing.

In the course of his career, Perez has seen companies like Accenture, Cognizant, Appen, Samasource (now Sama), and Lionbridge expand “human-in-the-loop” operations in countries like India and the Philippines for their biggest clients such as Facebook and Visa. Now, according to NASSCOM, a quarter of all time on AI projects is spent in data labelling. [2] “If not the most important thing, it is among the critical and highly important aspects of building and training complex systems,” said Jesse, now an early team member at Surge AI, a labelling platform that doesn’t outsource work abroad.

“Data work has a racial and class dynamic. It is outsourced to developing countries while model work is done by engineers largely in developed nations. Without their labour, there would be no AI.”

But in the larger conversation around AI, data work is often invisibilised. “The person making the AI doesn’t know about it, the government doesn’t know about it, you and I don’t know about it,” said Sarayu Natarajan, founder of Aapti Institute, a digital think tank that has researched the data annotation industry in India.

In a 2021 paper, scientists at Google Research argued that data is the “most under-valued and de-glamorised aspect of AI.” Developers huddle and collaborate around code, earning them prestige and career boosts. Model work is “the lionized work (of) building novel ... algorithms,” while data work is “grunt work.” The imbalance leads to a lack of quality data in high-stakes domains. The paper calls for a shift: researchers need to recognise “data as valuable contributions in the AI ecosystem.” [3]

“Data work has a racial and class dynamic. It is outsourced to developing countries while model work is done by engineers largely in developed nations,” said Nithya Sambasivan, the lead author of the paper and a former research scientist at Google. “Without their labour, there would be no AI.”

I interviewed 28 industry employees for this story, but not one commented, or appeared concerned, about exploitative labour practices in the data supply chain. Four annotators, all employed by iMerit, did complain that their salary was too low and hadn’t been adjusted for inflation in recent years. (In order to receive access to iMerit, the company asked that I not share exact salary numbers.) But none of these individuals appeared to give much thought to my questions about the big global debates in data labelling outsourcing.

Mujeeb Kolasseri, the founder of Infolks, brushed aside the question entirely. “Take the Burj Khalifa in Dubai. The engineer built the plan. But it was thousands of labourers over many years that made it possible,” he said. “The whole credit goes to the engineer who designed it, but without the labourers, he cannot build. We don’t care. For working people, they are getting paid. They are satisfied. If they are fine, then why do we need to think about it?”

A New Company in Town

ut of the seven data labelling company CEOs I spoke to, Mujeeb was unique. He had been a labeller himself, and came from a working-class background. To support his family, he’d dropped out of school in the twelfth standard and taken up odd jobs such as aluminium fabrication, rubber tapping, plumbing, and driving.

In 2014, when he was 23, he signed up on Amazon Mechanical Turk. His work on the platform was noticed by a German company, which had built a data annotation tool that had been acquired by a Silicon Valley-based technology giant. The German company’s managers got in touch and asked Mujeeb to set up a small team with whom they could contract directly.

With an initial investment of ₹25,000 and six employees, Infolks began to operate out of Mujeeb’s family home, a small cottage in Mannarkad. Staff grew to a hundred in less than two years. “I didn’t know what annotation was,” Mujeeb told me. “I didn’t want to know. I didn’t have any degrees. They gave me instructions, I got paid.”

Then the German client wanted him to hire 2,000 more employees for their work. It was at this point that Mujeeb realised all his work so far was just a pilot. (He later learned the labelling was meant for an autonomous vehicle project.) Intimidated by the scale, he forfeited the deal. “We aren’t based in a town. This is a village. Where are we going to find that many people?”

Many of the Infolks employees I spoke to looked back at 2018 as a dark time for the company. But just months later, the company won a contract with Daimler, the parent company of Mercedes-Benz. “That was survival,” Mujeeb told me. “If I didn’t do it, I would have had no work. I didn’t think of becoming a big company. I just wanted a proper income for my family and jobs for my employees.”

In just over four years since, Infolks has worked with over 130 clients, mainly from the US, Australia, Israel and Europe. One of their 40 live projects is with a FAANG company. [4] A third of Infolks’ roughly 500-person workforce is female. Almost 95 percent of the employees are just out of college.

Near the town centre, the company has two nondescript office buildings, one of which houses over 200 employees dedicated to their largest contract: labelling road scenes to aid an autonomous vehicle project for Continental AG, the German automotive parts manufacturing company.

In the next two years, Infolks hopes to expand to 2,000 people. Employees told me that Infolks was the best job that could be found in the locality, even district. “I don’t want to go outside,” Mujeeb said, “I want to bring work here.”

Lining the main road alongside Infolks were small wooden mills, steel and iron factories and the panchayat office interspersed with forests of palm trees. Glass showrooms were followed by thatched-roof cottages. Farther away from the town centre, and spreading for miles, were rubber and coconut plantations, paddy fields, and trees of teak, tamarind, mangos, badam, areca nut, bananas and jackfruit.

Against the Odds

fter crossing many of those fields on a windy road named after Tipu Sultan, I reached the house of Neethu Das. Here, on a terrace overlooking a pineapple and rubber forest, she teaches Bharathanatyam to young girls every Sunday. A class was in progress when I visited, and Paru, Neethu’s two-year-old daughter, was transfixed by the footwork of the ten dancers. (We communicated through a translator, and a press relations associate was present during my visit to Neethu’s house.)

Neethu’s husband had been physically abusive with her after she got pregnant. He wouldn’t let her apply for jobs or teach dance. Around that time, Neethu heard of the new IT company in Mannarkad, 15km away. After graduation, and behind her husband’s back, she applied for a job there. She bagged the role just a few days after filing for divorce. It was a new beginning for her in more than one way.

A few days before I went to Neethu’s house, I had met the 26-year-old at the Infolks office. “I have a feeling that I’m part of many technologies that we see,” she said when I asked if she knew why she was labelling CT scans of the brain. “The work I’m doing is someone else’s dream. It’s my client's dream. To be a part of that development makes me happy.”

In her house, there were four generations of women living under one roof. “The job came like rain in the desert,” Nisha P.V., Neethu’s mother, said, over the sound of Paru’s cooing and their dachshund’s barks.

“Amma, I explained to you what Neethu does, didn’t I?” Nisha asked Leela, the eldest of the four generations. “I think even the escalator is working because of her work. Automatic doors, sensors, robots, automatic cars. It’s just that everyone is surprised there is an IT company in Mannarkad.”

The women sleep in the same hall. If they hear any strange noises, Nisha is the person designated to go outside and check. She’s trying to instil the same confidence in the next two generations. “I want to teach Neethu to ride a Bullet, but her arms and legs are too short,” she said, laughing. “First, I will teach Paru karate.” She hoped her granddaughter would be bold, and live wherever she wanted. “She can explore the world and gain knowledge.”

One person who was already displaying this streak of boldness was 24-year-old Padmapriya P., who I met at the Infolks office. Sitting in a long, narrow glass room in the building’s basement, I watched as she labelled busy roads to train driverless cars. Her hair was tied back in a long ponytail, and she wore stylish glasses.

An accident had turned her life inside out. In 2018, she had gone to Palakkad with her family to accept admission to a management course at Calicut University. As they were crossing the road to reach the university, disaster came in the form of a hurtling lorry. Her mother disappeared under the vehicle while a tire zipped over Padmapriya.

Miraculously, they survived. Her mother was left with a brain injury and a loss of flesh on both hands. Padmapriya had to have her right leg amputated.

Three years and seven surgeries later, Padmapriya’s mother has regained movement in her hands and legs. Padmapriya, for her part, has been through many plastic surgeries and walks with a prosthetic leg. Defying all odds, she became the breadwinner of the family by joining Infolks in 2021. (Her father quit his painting job to help his wife.) Her salary helped chip away at the debt of ₹30 lakh the family incurred to pay hospital bills.

“I never thought that I could go to work within three years,” Padmapriya told me in her home, 11 km away from the office. “There was no one telling me that I will be okay. I was not that bold before the incident. But without financial stability, we couldn’t move forward.”

It took her some time to understand the context of the work she does at Infolks. “We are doing the basics of artificial intelligence,” she explained. “If the base is strong, only then will the rest be strong.”

She hopes to continue her MBA at some point. With friends at work, she jokes that there will come a day when the robots will learn everything, and the humans will be out of work. But it’s partly true, she believed. “I don’t know if this data labelling will be there,” she said. “Aren’t robots doing almost everything right now?”

Bot Armies on the Horizon

admapriya’s boss, Mujeeb, also predicted that the field will experience a tectonic shift in the next five to ten years. One of his plans is to establish a research centre in Calicut to look into new business strategies.

“Call centre jobs are now taken over by bots,” he said. “These jobs might also disappear. Five years back, we didn’t even know about this industry. I don’t know when it is going to end, but there will be an end.”

Avinesh Vazhakkat, a former Infolks employee, shared an anecdote to explain this fear. In 2019, he accompanied Mujeeb to a conference in Bengaluru. An automated annotation tool was showcased there. “Mujeeb and I thought we would have to shut down in five years,” he said.

But Jesse Perez, the former Meta executive, was more circumspect about a future bot takeover. “Humans in the loop will probably be needed for a really long time,” he said, “but the type of roles might change.” What he said reminded me of a line I read in Ghost Work, an important book on data labelling by the anthropologist Mary L. Gray and the computer scientist Siddharth Suri: “The great paradox of automation is that the desire to eliminate human labour always generates new tasks for humans.”

However, the future humans-in-the-loop may not be from the same background as the people I met in Ranchi and Mannarkad. According to Jai Natarajan, the shift will come from the need for “experts in the loop.” As the requirements for training become more specific and more complex, companies like his may need to hire more specialists and domain experts, such as practising radiologists.

“We are in a race for people to do better than the algorithm,” Jai said. “That’s how we can babysit the algorithm. They might begin asking: Is the ear of this corn diseased? Does this wind turbine have damage? You start to raise the bar for humans too.”

But, at the moment, a large landscape of basic training remains untouched. “If we built a model that found diseases in oranges, the same model can’t find diseases in apples,” said Jai. “There is an infinite level of last-mile customisation.”

“We are in a race for people to do better than the algorithm. That’s how we can babysit the algorithm. They might begin asking: Is the ear of this corn diseased? Does this wind turbine have damage?”

NASSCOM predicts that, with most labelling companies in their early growth stage, the industry has a runway of a decade or so. The market could grow to support a workforce of between five and 10 lakh people over that period. In its National AI Strategy of 2018, Niti Aayog, the apex public policy think tank of the government of India, commended the field of data annotation for job creation and called on the government to look at the industry to absorb the workforce that might be replaced by automation.

By then, Pushpi Shankar hopes to have started her own business, “if God is with me.”

On my first visit to iMerit’s Ranchi office, I saw Pushpi breastfeeding Yashika, her 6-month-old baby, under a chiffon scarf in the training room. She had been encouraged when she heard that Alvina Tirkey, a colleague, had brought her nine-month-old into the office. (A third woman employee told me she had asked the management about hiring a day-care service.)

Pushpi had no option but to bring Yashika to work. Her parents-in-law, based in Bhagalpur, didn’t support her work and had asked her to take two years off to take care of the child. Her own parents were upset that she chose a love marriage. Her husband, while open to Pusphi working, leaned towards his parents’ point of view in arguments.

“After I got married, I started to work more and save my money,” the 29-year-old said. “I understood that if I don’t save for myself, then anyone, anywhere can push me around. Tomorrow, even my husband could leave me. I fear this sometimes. But I don’t get scared if I am earning.”

She’d just joined iMerit when I visited. She spent the next two days learning about her new job and passing her baby around to everyone in the office. Some of her colleagues were filling out quality parameters on a spreadsheet, others were on calls on Google Meet, and the rest were carrying out a wide range of labelling tasks on images of streetscapes, geospatial graphics and Instagram videos.

Chandmuni, the woman from Pungi, told me she had seen several of her colleagues bring children to the office. In discussions about her own wedding, she had made it clear to her potential in-laws that she will continue working and will complete the final year of her Master’s. “If I worked so hard to get here, how can I not keep working? I will work; only then will I be able to live.”

Chandmuni dreams of going to Mumbai or Delhi. She laughed continuously as she told me this, as if it was an absurd thing to admit. She had only left Jharkhand once: to go to neighbouring Odisha, and even that train ride felt ambitious.

“Sometimes, I think that my day will come,” she said. “If I came to Ranchi by myself with my own determination, why not go further?”

Karishma Mehrotra is an Indian American journalist and academic living in India and focusing on issues of the future: technology, climate, urbanisation, and migration. She has worked at or with the Indian Express, Wall Street Journal, CNN, Scroll.in, the Boston Globe, Bloomberg Business week, the Earth Journalism Network, and the World Bank. She is currently completing a Fulbright research grant in Bihar and Jharkhand.