Paradigm / Shift: Stories of innovation, shaped by intelligence.

Editor’s note: This story contains inputs from the team that brings you Paradigm Shift, a podcast hosted by Harsha Bhogle. This story and the podcast are brought to you in partnership with Microsoft India.

Anand Verma is the first engineer in a family of farmers. Some years ago, while also holding a day job with an IT company, he was running two farming experiments. In Mysuru, he and a partner were growing coloured capsicum. The other project was at his father’s cauliflower farm in Azamgarh, Uttar Pradesh. For that, he built a DIY moisture measurement unit to manage irrigation schedules. “The capsicum experiment didn’t work,” Verma says, “but the one on my father’s farm did.”

His learnings sowed the seed for the founding of Fasal, a company that builds hardware for precision agriculture. Fasal is one of a new breed of B2B focussed Indian start-ups that observers are calling the third wave. [1] (The first began in the years right before liberalisation in the IT off-shoring era; the second rode on the consumer wave of the new millennium.)

Among India’s third wave of start-ups are several that have turned to artificial intelligence-based solutions to solve large-scale problems. Perhaps no problem looms as large over humanity as the planet’s environmental degradation. The last few years have seen a much-needed international awakening around the issue of climate change. The Paris Climate Agreement and the United Nations’ 17 Sustainable Development Goals are no longer just buzzwords in large organisations: they are seen as opportunities to both service the bottom-line and do the right thing. In other words, organisations mostly agree that the climate crisis is urgent and ignoring it would be costly. In India, a cohort of driven entrepreneurs are primed to help them.

The group is diverse. There are people such as Verma of Fasal and Sarvotham Pejavar of Zecomy, who worked for several years in banking before swerving into entrepreneurship; like FluxGen’s Ganesh Shankar who had a brush with environmental activism in his childhood; like 23-year-old Angad Daryani of Praan who has not known a world where environment cataclysm was never a talking point. Here are their stories.

Testing the Waters

anesh Shankar grew up around the Madiwala lake area in Bengaluru. When he was a child, it was suggested that the lake be drained to build a new neighbourhood. The growing city needed more space and Bengaluru turned to the lakes to create them. The people around him fought back, and among their many awareness campaigns was a painting competition. Shankar won that competition. So did the people. The lake remains. He still has the environmental encyclopaedia he received as a prize, and remembers what he learned from it.

He now runs a company called FluxGen whose stated goal is to save a billion litres of water a day. “That is about as much water that Bangalore is taking from the Cauvery,” Shankar explains. “What I mean to say is, if we are able to reduce nearly 15 to 30 percent of water consumed in an industry, and each industry can save a million litres per day, then with a thousand facilities, we can save a billion litres of water. That is equivalent to setting up hundreds of lakes through conservation.”

We will help you reduce water usage by 30 percent: that is FluxGen’s pitch to potential clients. The company’s core offering is an artificial intelligence- and cloud-based product that profiles the water consumption pattern of a company and pinpoints exactly where there are leakages or wastages.

If you consider this a simple measurement, an AI-based solution might seem like overkill. But there are multiple data points in an industrial faculty’s water-use pattern. Acquiring water is expensive and energy-intensive if groundwater is depleting. Over and above that, there are the processes: pumping, purifying, freezing, boiling, to name just a few. Studying these processes goes beyond measurement—it requires data across various features and their interdependencies (such as, for example, energy bills) for all those water-related processes. That’s why FluxGen uses both Microsoft’s Azure for cloud computing, and a machine learning algorithm to make sense of water consumption.

“At the end of the day, sustainability is a business imperative,” Shankar says. Clients don’t have to choose between environmental concerns and the bottom-line, because these solutions are intended to save on other costs. “When I chose this career, I chose it for environment & sustainability. But to my customer, I look for a financial return or investment,” Shankar says. For FluxGen’s clients, it’s also a matter of their compliance and storytelling requirements. Sustainability is now a matter of wide public interest, and customers are looking more favourably on companies that are thinking deeply about the environment.

“When I chose this career, I chose it for environment & sustainability. But to my customer, I look for a financial return or investment.”

There hasn’t been a more exciting time for start-ups working on sustainable solutions. “Having a start-up is like having a guitar in college these days,” Shankar laughs. He was betting on it: nearly 12 years ago, he left a well-paying job at General Electric Energy to build a career in sustainability. His first venture was a project-and-consulting company. One of their early successes was arranging for solar power in a village that had never had electricity before—a Swades moment if there ever was one. That company was the early avatar of FluxGen, which he turned into a pure product company in 2019.

Shankar currently spends a lot of time building relationships within the sustainability ecosystem. He’s founded two non-profits called Wednesdays for Water and the Sustainability Engine Foundation. While ‘Wednesdays’ gathers experts who work on water solutions once a week, the SEF runs the Sustainability Mafia, an ecosystem of sustainability leaders who seek to build goal-oriented collaborations.

These networks have come in handy, especially in the last couple of years. In March 2020, the G. Kuppuswamy Naidu Memorial Hospital in Coimbatore was looking to manage its water resources. The process had to be stalled since mobility was restricted during the nationwide lockdown. Happily, one of the members of the Mafia offered to coordinate the installation of the product on FluxGen’s behalf. FluxGen sent the hardware and then conducted online training sessions. It was a success. Shankar says the hospital’s water usage dropped by 36 percent: from 500,000 litres to 320,000 litres.

Shankar remains committed to the cause in his personal life, too. “I am 38, I still don’t have a driving licence or a car,” he says. While he doesn’t see a need to impose that choice on individuals, he hopes that industries and corporations adopt conscious consumption at a large scale. It could save some lakes and leave more water for the future.

Cream of the Crop

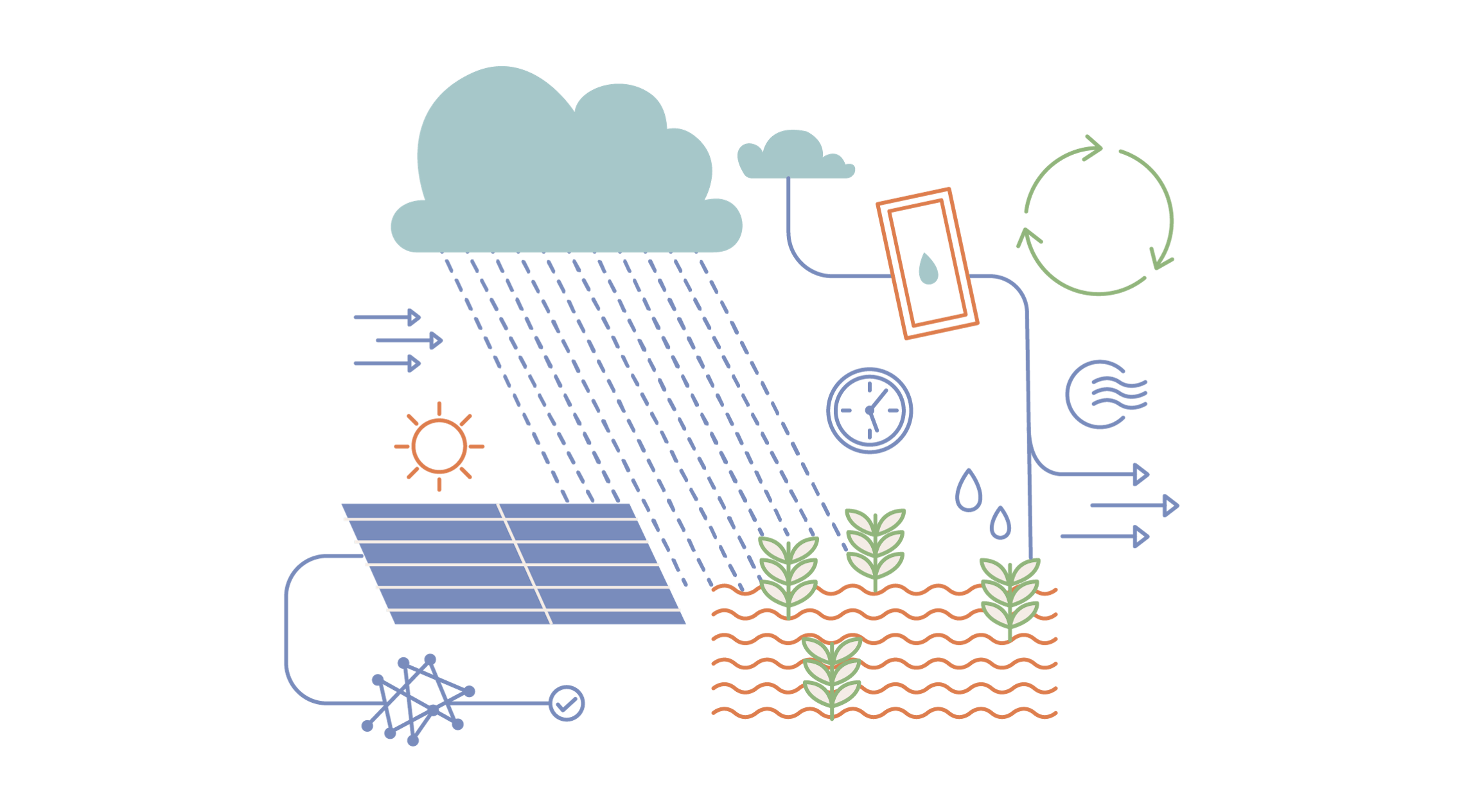

asal’s core product borrows from the DIY machine that Anand Verma built for his father. The upgraded version looks like a giant ‘Y’-shaped metal scarecrow towering in the middle of a field. It is fitted with solar panels, WiFi signals, electric boxes and data-collecting sensors. Some of its sensors detect rainfall, wind speed, wind direction, and solar intensity; others detect temperature and humidity; and another set, below the soil, measures soil moisture, temperature and electrical conductivity.

All this information is transferred to the cloud via the two little dishes on top of the metal scarecrow. The algorithms then work their magic to address the one question that farmers are constantly thinking about: mujhe paani kab daalna hai? When should I water the crops?

Growing up, Verma watched farmers rely on intuition and traditional knowledge to chart a “static calendar schedule” for different crops. From their long years of experience, they knew that crop A required watering every three days for the first two months and then once a week in the third month. It’s the kind of knowledge that has sustained agriculture for longer than can be stated.

This is changing. Among the many disastrous effects of climate change is how it makes weather, soil and water conditions unpredictable. In five decades, the environments our crops will grow in will not look like the ones five decades back. In fact, we may not even be eating the same crops. Genetically modified and hybrid crops will perhaps play a bigger role in meeting global nutrition needs. “When all these fundamental things are not going to remain the same, how can we rely on the same static practices?” asks Verma.

With Fasal, Verma’s idea is to eliminate guesswork and build a system that helps farmers and crops “talk to each other.” “So when the crops are thirsty, hungry or sick,” Verma says, “farmers can respond appropriately.”

He and his team looked at both satellite and drone imaging, better developed technologies at the time, before turning to AI solutions. But the team didn’t take long to realise that these technologies were documenting the present rather than being predictive of the future. “If something has already happened,” Verma says, “I have already lost.”

The other reason they decided to go with an Internet of Things-based solution was the sheer volume of complex data they would be dealing with, like FluxGen. Some of these metrics are not as straightforward as temperature. To make his point, Verma explains the concept of evapotranspiration, the combined process of evaporation and transpiration that helps arrive at how much water—effectively—a crop has lost. Metrics like this need to be adjusted with other factors like crop physiology (four-day and 40-day old crops have different water requirements), soil moisture and daily temperatures. Working out the relationships between these factors, on a dynamic and real-time basis, is a task only AI can manage.

“We create these AI models where we feed all this data and this black box is nothing but the algorithms that we have written. That crunches all the data,” Verma says. “All of this is to provide farmers with an outcome on an SMS or the Fasal App, saying that you need to water your crop, five litres per plant, at six o’clock tomorrow,” says Verma.

Despite the simplicity of the process for the farmer, taking the product to market wasn’t without hitches. It was going to be counter-intuitive to rock up to farmers and ask them to tweak time-tested practices. Instead “we changed our messaging,” Verma says, “and told them, look, what we are providing you is nothing but a stethoscope that will help you understand your crop better. You’re still the doctor.”

The next steps for Fasal are clear. They have to reach the farmers growing crops that are more essential to our diets like rice and grains. By 2050, the world will have to feed nearly 10 billion people and we cannot afford to wait until then to take measures. Proper watering, enabled by Fasal’s assistive technology, could mean more yield for farmers. That is a starting point. Verma also harbours the hope that these yields will be of higher quality and can compete with exports to other countries.

Breath of Fresh Air

hen Angad Daryani arrived in the United States of America to study engineering, he realised he could breathe better. Growing up with asthma in Mumbai, he was acutely aware of India’s diminishing air quality. “Climate change was 30 to 50 years on the horizon but air pollution was already killing millions of people. While I could move to another country with a better environment, I could not expect my family and friends to do the same,” he says.

“My parents’ generation grew up with the promise of an exciting future, whereas my generation grew up with a promise of a bleak future. Icebergs are melting, animals are extinct, air is polluted, water is polluted. That’s not an exciting future to wake up to everyday.”

The best way to address this discomfort, Angad felt, was to try and solve what was bothering him. He was 19 then and in his second year of engineering at the Georgia Institute of Technology, Atlanta. If he tried something and failed, he would still be a 19-year-old studying at a top technology university.

“If I want to build the most expensive, fancy, luxurious air purifier, I can do that in the Valley or some parts of Europe. If I want impact and scale, I should have an Asia counterpart.”

He started building his prototype of an air purifier. The HEPA filter, in its current form, isn’t yet a sustainable solution for large outdoor areas. The filtered air purifiers that suck out particulate matter do their job inside a room in a house or an office. But they can’t reasonably be deployed in high-density open spaces and pollution-producing industrial environments. The HEPA filter in such a situation would need replacing every couple of hours.

Daryani decided to self-fund his solution so he could retain the intellectual property. He worked in the lab after classes. The lab wasn’t open to undergraduates at night, so he’d lug his 20-foot contraption back to his room after hours. It caught the eye of his fellow students. When CNN featured him in their series “Tomorrow’s Hero,” the three-minute video clip went viral.

The first employees of what would become Praan were 32 volunteers who worked on the product the next semester. Daryani had no money to offer but could promise that everyone who worked on the product would be recognised in any eventual patent. The number of volunteers doubled in the next semester.

In early 2020, the company needed around $1.6 million, but investors stepped back from their verbal commitments when the pandemic hit. Daryani held on to his network and tried to make do with the ₹10 lakh he had taken from family and friends. By the end of 2021, he had a couple of grants come through from Emergent Ventures. Emergent was also able to connect Daryani to venture capital fund Social Impact Capital. That changed the course of the company. Daryani made his first dollar from the company in November, five years after its founding.

Praan now makes something they call the MK One. It’s a low-cost, low-maintenance product that can lead to a 30 to 40 percent drop in particulate matter. In most cases, a facility needs to only empty the collection chambers once a month, a 30-second process. In facilities where there is sticky dust—Daryani mentioned one of that kind in Gujarat—the collection chambers need to be cleaned out once a week. “The goal is to capture particulate matter at a higher rate than they are introduced at,” which is what the filterless technology hardware for MK One and its accompanying ML-driven algorithm in the cloud works to accomplish.

Praan surveys each site beforehand. They use this data to train the algorithm (Praan also uses Microsoft Azure’s tech stack for cloud operations). “Most air quality data available on the internet is from unreliable monitors,” Daryani explains. “People buy either cheap monitors or use indoor sensors outdoors because they are affordable.” In order to strengthen the company’s credibility, they began building their own sensors.

It’s an approach that complicates the workflow at an early stage but Daryani is reluctant to compromise. He has also moved to manufacturing the main hardware MK One because using external fabricators was proving far too expensive and unreliable. “Manufacturing is hard but it’s not impossible,” Daryani says. When I spoke to him in the last week of May, the first batch of 25 MK Ones manufactured entirely in-house were almost ready to go.

Every day, Daryani says, he receives fresh inquiries for the MK One, not just from India but from Singapore, Malaysia and the US. But he has no plans to move operations. India is where he has to be. “You can’t build a full climate company in the US and scale it,” he says. “If I want to build the most expensive, fancy, luxurious air purifier, I can do that in the Valley or some parts of Europe. If I want impact and scale, I should have an Asia counterpart.”

Daryani is 23 now. He hasn’t thought about selling his company or its IP. He does not want his product to be one of 50 in the warehouse of some industrial giant, responsible for a blip on a balance sheet. And, he says, “Even if I get a billion dollars tomorrow, saying we’ll buy this company out, give us your IP, you work with us for a year or two, serve your pay and leave, the problem won’t be solved.”

Recycle Bins

he difficulty of access to clean air and water are problems everybody can agree on. These are resources, finite and necessary to our survival, that require urgent attention to breathe and live. There are others that have endless potential to be further mined. One of these resources is our trash.

Sarvotham Pejavar worked in banking for nearly three decades before he started Zecomy with his partner, Devarayan Chidambaram. When they started, the company focussed on managing e-waste: old smartphones, laptops, tablets. They took in the e-waste, dismantled it safely, sold the recycling parts to secondary buyers and discarded the unusable parts. “But clients came back and asked, why can’t you help us with our lead batteries, metal scraps or packaging materials?” Pejavar says.

He had an inkling of what was happening in parallel, in another business: fashion. Here, conscious consumers were increasingly buying and donating to thrift stores. Companies were talking about becoming carbon neutral by 2050, fulfilling one of the UN Sustainable Development Goals.

Pejavar decided to expand Zecomy’s operations beyond just e-waste. “Today, waste management is the least important area for any organisation,” he argues. “Everyone talks about how the payment settlement has to happen, how the customer experience should happen, how businesses have to be grown.”

Zecomy wants to build a circular economy. This is simple enough to understand but hard to achieve. You’ve probably seen the 4Rs in posters or banners. These are ‘refuse,’ ‘reduce,’ ‘reuse’ and ‘recycle’—four easy-to-remember calls to action to help individuals be environmentally conscious. Zecomy expands the 4R framework to a 10R one, adding rethink, repair, refurbish, remanufacture, repurpose, and recover to the list. “The goal is to retain as much value as possible from resources, products, parts, and materials to create a system that allows for a long life or optimal reuse, refurbishment, recycling.”

Today, Pejavar estimates, this circular economy market is roughly worth $40-50 billion in India alone, with growth expected to double in the next five years or so. He calls it “a great opportunity” not simply for increasing the value of our waste but also to generate thousands of “green jobs.”

“The big companies are looking at start-ups to solve problems. In the next two decades, most people will be job-givers and not job-takers.”

So where does the AI come in? By now, you have a sense of how some Indian start-ups use a three-pronged template of hardware on field, a cloud service with an ML algorithm trained on relevant sets of data, and a communication model to deliver insights.

Zecomy’s data collection takes place at two levels. Its model must chart the landscape of actual waste and the network of people already working in waste management. For the first, the data must develop and record a “scientific pathway” for every kind of material from segregation until disposal or reselling.

The second problem is arguably more challenging, simply because large parts of the human resource in waste management are fragmented and informal. Most urban Indians have met door-to-door collectors of waste materials, or municipal workers who take charge of public bins. Beyond that, secondary market buyers and sellers have their own networks. If you add policy advocates who advise governments and corporations, you get a fuller picture of the number of people, and the diversity of their jobs, committed to the cause.

Zecomy enters this equation to map networks for segregation, as well as to connect people from different parts of the network. They’re serious about bringing structure and transparency to a process that can be notoriously opaque. For example, one of the things they do is vet vendors to ensure that they are following a sustainable pathway in operations and also complying with labour regulations (India’s informal sector of waste pickers enforces labour on children at a large scale.)

AI helps Zecomy “understand what kind of material can be extended back, how it can be done, how many guys are interested to make use of it, which kind of market it can hit, who are available there,” Pejavar explains. Additionally, it can help with commodity pricing. More often than not, people in the secondary market do not know the true value of what they hold. With price points factoring into the algorithm, Zecomy can offer buyers and sellers a marketplace.

During the pandemic, Zecomy also moved into project management after clients came to ask for help with relocation and office closures. They offered an end-to-end solution for the process: from disposing cables to carpets. Every single piece was accounted for and clients got detailed reports on what happened to the debris after they left the office. It’s working out well: 80 percent of their clients, they say, are Fortune 500 companies across 19 industries.

here’s no better time for AI start-ups that want to make the world greener. “The big companies are looking at start-ups to solve problems,” Pejavar says. “In the next two decades, most people will be job-givers and not job-takers. We are evolving every year. The government is making good moves, private companies are accepting them and everybody is acknowledging the problems.”

Everybody I talked to for this story agreed there was a hunger for new ideas and a willingness to invest in them. In 2019, funding for Indian AI start-ups had hit $762.5 million, a whopping 44 percent growth from the previous year. [2] The pandemic put some spokes in that wheel but start-ups were quick to adapt. In 2021, there looked to be an “up” cycle again, with funding for AI and analytics startups crossing the figure of $1 billion. Another piece of encouraging news was that start-ups in cities like Chennai and Patna joined the usual suspects Bengaluru and Mumbai.

Sustainable solutions are going to reach our homes and our lives in more ways than we think. They’re already transforming how we choose to act at the intersection of business and social change. The challenges facing us aren’t small. But, as Pejavar says, it is important to put in the “right effort.” “You may not get success on Day 1,” he continues, “But if you are steadfast, learn from issues, keep your ear to the ground, you will succeed in the years to come.”

That isn’t a breeze. But progress has to be seen as achievable and real in order to be made at all. If that is difficult to internalise, look to the people who are making tiny dents. In time, there will be a crack. That’s what they believe—and hope is infectious.

Amal Shiyas is an assistant editor with FiftyTwo.