In 1978, Chonira Belliappa Muthamma was serving as India’s Ambassador to Ghana when she received a missive from Jagat Mehta. The letter informed her that she was not up to the task of succeeding Mehta as the country’s foreign secretary. [1] She was taken aback. Her resume was formidable. In 1948, she had become the first woman in free India to top the civil service examination. In the decades since, she had served in embassies around the world, including in London and Paris. Within the Ministry of External Affairs, she had worked on two of the most prestigious desks: Pakistan and the Americas.

She was met with silence when she wrote back requesting clarity. When Atal Bihari Vajpayee, then foreign minister, arrived in Nairobi for a conference in February 1979, Muthamma asked him how merit was assessed in the system. “If you don’t tell me, I’ll go to court,” she warned. “Don’t do that,” Vajpayee protested. But that is precisely what she did.

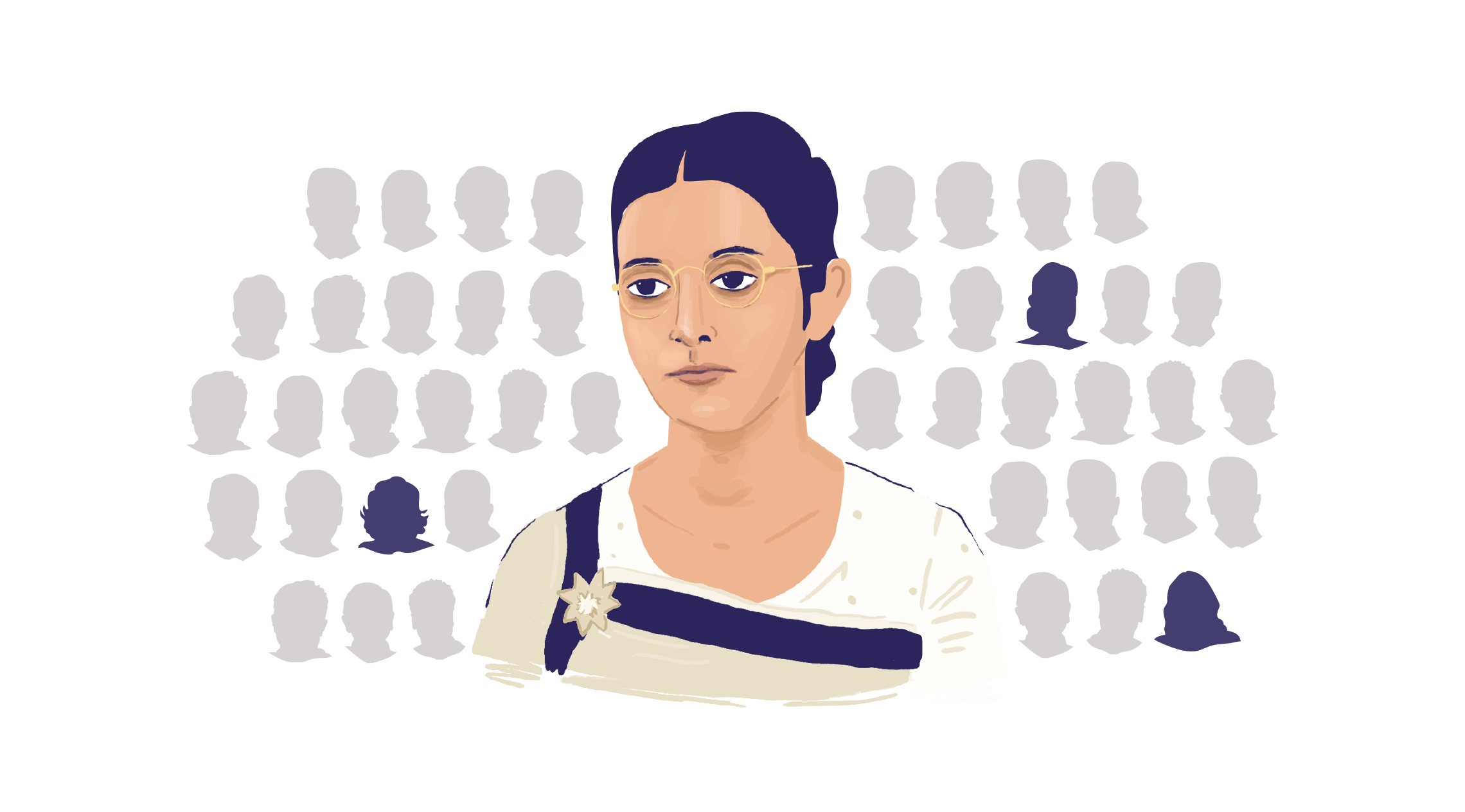

In her writ petition, Muthamma contended that by being denied promotion to Grade I of the Service, she had been discriminated against on the basis of her gender. On 17 September 1979, the Supreme Court gave its judgement in C. B. Muthamma vs Union of India & Ors. “Unconstitutionality is writ large in the administrative psyche,” Justice V.R. Krishna Iyer wrote. “This misogynous posture is a hangover of the masculine culture of manacling the weaker sex, forgetting how our struggle for national freedom was also a battle against women’s thralldom.”

Origins

Looking back, I cannot help but conclude that my entire tenure with the External Affairs Ministry was one long tussle with the anti-woman bias,” Muthamma wrote in her collection of essays titled Slain by the System: India’s Real Crisis. She was to have considerable trouble making peace with this fact, given that her early years were defined by her mother’s independent outlook and women’s participation in the freedom movement.

Home, for the young Muthamma, was the tiny town of Virajpet in Kodagu, nestled in the thick forests of the Western Ghats. Born on 24 January 1924, she was the eldest of four children. Her mother had been taken out of school when she was 12, to safeguard her for the natural progression to marriage and children.

Muthamma's mother grew up with a keen awareness that some doors were closed to her simply because of her gender. She was, for instance, an excellent shot. Nearly every home in Kodagu had a gun in those days, but it was off-limits to women. She found it infuriating that girls were denied access or privilege on account of their gender. She was the first feminist in her elder daughter’s life. By all accounts, she was the parent who shaped the woman that Muthamma would grow up to be.

She had to bring up four boisterous children without the partnership of Belliappa, Muthamma’s father, who passed away when she was nine years old. Muthamma was sent to Madikeri, to St. Joseph’s Girls’ School, and then to Presidency College in Madras for her college degrees. Nobody, not even Muthamma, understood why a young widow was insisting on educating her three girls. “One result of her support,” Muthamma later wrote, “was that I was not really aware, until I joined the Foreign Service, that women were considered second-class humanity.”

Muthamma went to college during the high noon of the Indian independence movement. Across the country, women marching in defiance of the Raj were subjected to police brutality and lathi charges. During the Quit India movement of 1942, representatives of student organisations came to Presidency College to exhort the girls to go on total strike. “Our sympathy with the freedom movement was total,” Muthamma wrote, “but I found myself wondering whether this particular way of demonstrating solidarity was the best.” Many young men and women who were considering a career in the administrative ranks shared Muthamma’s dilemma.

Freedom

History,” Muthamma liked to say, “is created from continuous streams of action, of choices made by faceless and nameless masses of people.” In her final years of college, Muthamma had already started grappling with questions about the price of freedom. In the wake of its liberation, what direction should the young nation take?

Despite the ominous portent of Partition and the challenges of integration, these were days full of optimism. For once, gender didn’t appear to be a handicap. Gandhi had changed the world of nationalist participation for women across the country, from satyagraha to picketing to breaking the salt laws. [2]

In 1944, a tiny silver-haired woman named Vijayalakshmi Pandit blazed a new trail in the United States. For two years, she gave lectures around the country, making a passionate case for decolonisation and the emergence of a new world order. Pandit, who became one of independent India’s most prominent diplomats, was the sister of India’s prime minister-in-waiting, Jawaharlal Nehru. Her familial connections opened her up to criticism. There is no doubt that she used her privilege to her advantage: there were shopping trips with writer Pearl S. Buck and lavish dinners with Eleanor Roosevelt. But along the way, the “Woman Who Swayed America” collected a formidable list of allies.

“It was Pandit’s class and caste privilege that gave her better access,” the scholar Khushi Singh Rathore wrote in an email. “But what she made of that access is another story.” [3] The hazards that came with gender were yet another. She was asked, to her annoyance, what kind of clothes she’d wear on her lecture tour. On another occasion, an enthusiastic male listener called Pandit at her hotel after a lecture. “Honey,” he exclaimed, “I didn’t listen much to what you were saying, but your voice is like moonbeams and honey, and I love you, and I’m on India’s side!”

At the inaugural session of the UN, American newspapers were gushing about India’s commitment to women’s representation.

Other Indian women were registering their presence on the international stage, too. Hansa Mehta played a key role in the drafting of the Universal Declaration of Human Rights. Begum Shareefah Ali was a founding member of the United Nations Commission on the Status of Women in 1947. Lakshmi Menon headed the UN’s women and children section between 1949 and 1950. Renuka Ray represented India at the General Assembly in 1949. At the inaugural session of the United Nations, American newspapers were gushing about India’s commitment to women’s representation.

This is the sphere of influence that Muthamma entered after graduating college in 1948, only to discover that it was a minefield.

The Service

n September 1947, Sir Girija Shankar Bajpai was an anxious man. Bajpai was the secretary general of the Ministry of External Affairs, Nehru’s main man on foreign policy. He was staring down the barrel of a personnel crisis in India’s administrative services. How would he staff the diplomatic corps?

The Second World War had frozen fresh recruitment in the higher levels of the civil services. Administration across the country had nearly buckled in the wake of Partition. Veteran officials had been reshuffled across the subcontinent. Nearly all British officers had resigned, and many Muslim officials had opted for Pakistan. Those Europeans who wanted to stay and serve India were turned away by Nehru. [4]

By April 1947, it was estimated that 152 officers would be needed for missions abroad, but only 36 candidates had actually been hired. By May 1947, out of 288 applicants, only 152 had actually managed to make it through to the interview stage. [5] “There was no natural pool, so the old generalist approach prevailed: take from the ICS and its allied services,” Ambassador K. Shankar Bajpai has written in an account of his father’s time in the Indian Civil Service.

In the spring and summer of 1947, V.K. Krishna Menon, High Commissioner to the UK, was travelling through European capitals. His dispatches to New Delhi were all about the world’s enthusiasm to engage with a free India. But Bajpai couldn’t see how this would be possible. In his estimation, the manpower shortage made the possibility of opening new missions abroad “scant in the extreme.” [6]

For his part, Bajpai had been advocating the creation of an elite diplomatic service since the 1940s. But Nehru was unconvinced, in no small part due to his instinctive mistrust of the ICS. “He found the officials he came across singularly lacking in his intellectual curiosity, not to mention his knowledge or breadth of vision. So, there was a sort of instinctive preference on his part to look for new instruments.” [7]

Bajpai had a different perspective. He argued that governments and systems could change, but they all required an administrative apparatus to function. On 10 August 1947, a committee chaired by Bajpai published the Report of the Secretariat Reorganisation Committee. The Report’s main thrust was that the core of India’s new administrative service must comprise experienced officials. [8] Bajpai was in favour of a “small service of highly trained professionals who would be the core of strategic thinking, and provide the foreign policy interest and inputs.”

“It was all rather ad hoc and hurried,” K. Shankar Bajpai remembered. A motley crew had been hastily put together for the new Indian Foreign Service. There were a handful of freedom fighters in a sort of hat tip to their contribution to the national movement. There was one ex-officer from the Indian National Army. At V.P. Menon’s suggestion, half a dozen young sophisticates from India’s princely houses came along for the ride.

Among Muthamma’s pioneering generation, there was a sense of excitement. There was also the singular anticipation of working for, and possibly interacting with, Jawaharlal Nehru.

The scholar Swapna Kona Nayudu offers an affecting glimpse of those early days. Muthamma’s batch of trainee officers were bussed across the leafy avenues of Central Delhi for a tea-time appointment with the Prime Minister at Teen Murti Bhavan. All of them clutched copies of his autobiography, hoping to get a signature. They were clustering nervously in the hallway when they heard brisk footsteps on the carpeted stairs. Soon, the Prime Minister was with them. The conversation that ensued was stimulating and lively—it covered a range of subjects from science to history to technology.

It was a heady time. There was the prospect of language training tours overseas—to Beijing for Mandarin, Cairo for Arabic and Madrid for Spanish. To serve in the IFS was a matter of both honour and prestige. The young officers may have been awed by Nehru but they had minds of their own. Nayudu’s interviews with former ICS officials revealed that the IFS was “sensitive to what he (Nehru) wanted, but was not invented by him.”

It was a time that heralded great change. India was watching the world as much as the world was watching India. And yet, the more things seemed to change, the more they remained the same. As Rathore observed rather tartly, “As an institution, the IFS borrowed heavily from the ICS.”

The Women

ir Hugh Weightman, still serving as Foreign Secretary in 1947, firmly believed that women had no place in diplomacy. Nehru, keen to shrug off the colonial burden, rejected this view. So when the first Public Service Commission examinations were held in the monsoon of 1948, Muthamma found herself in an examination hall along with a sea of men. She didn’t hesitate to write ‘Indian Foreign Service’ as her preferred choice of service. She topped the written test easily enough. “I was not a gender, but a statistic, a number.”

But the interview was devastating. At her viva voce, Muthamma faced a battery of men led by the Chairman of the Union Public Service Commission himself. All of them made it abundantly clear that a woman had no business aspiring to enter the portals of the Ministry of External Affairs. If Muthamma chose to continue, she would have to sign an undertaking that she would stay single for the rest of her life. In the event that she did marry, she would have to resign from government service. In the autumn of 1949, Muthamma signed the undertaking. The Constitution of India, with its guarantees for equality, would only come into effect some six months later.

“Having an enlightened Constitution and a supportive mother was one thing,” Muthamma wrote, years later. “Facing the traditional biases of men all through my career was another thing.” Muthamma heard of what had happened to the girl who had taken the examinations along with her. “She encountered an unsympathetic medical board. Finding nothing specifically wrong with her health, they disqualified her on the grounds that she was overweight for her height.” Soon, women recruited before the examination left, almost always due to the marriage rules. Others who qualified for the IFS opted to join the Home Services because their families feared the hazards of serving abroad.

In the first three years of service, Muthamma was at pains to prove that she was as good as any man. “The problem,” she would admit later, “lay in the psychology of the men.” Personnel at India’s diplomatic missions resisted Muthamma’s foreign postings, justifying it on pleas like, ‘She might have to go to the airport in the middle of the night.’

Eventually, the Ministry of External Affairs sent her out to her first posting in Paris, despite opposition from the embassy. Things improved somewhat after that big break. “The Political Counsellor in the mission where I was then serving had no option but to leave the work, including the reports, to me,” she wrote. “By the time he returned, both he and the men at the Ministry apparently came to the conclusion that I had not been a bad hand at tackling my responsibilities.”

Traditionalists

arly decisions concerning the recruitment of women in the IFS were “conservative,” former foreign secretary M.K. Rasgotra wrote in his memoir. Diplomats’ stories suggest that this was a colossal understatement. In the 1950s, as Muthamma travelled to Paris and Rangoon as part of her early postings, Mira Sinha Bhattacharjea cleared the IFS examinations. The young woman was chosen to be sent to Beijing, a particularly tricky posting that indicated her considerable talents. When she was called in for a briefing with Nehru, he looked at her somewhat disapprovingly. “I thought, am I wearing the wrong clothes, or is something wrong with me?” Bhattacharjea recalled.

What do you know about China, Nehru asked. “He said it in a tone that indicated that ‘You simply could not know anything about China,’” Bhattacharjea said in an oral history published in 2008. The prime minister, who’d ostentatiously rejected the idea of an all-male service, listened disinterestedly to her nervous reassurances before snapping: “No, I don’t like this.” He didn’t think women like Bhattacharjea should be in the Foreign Service. “You are depriving a man of his job,” he said. “You probably would get married and leave the service. All our investment would be lost.”

Muthamma was to witness too many qualified women opting for the Home Services simply because their families were fearful of the ‘freedom’ that was perceived to come with the IFS.

Rathore told me that even as Nehru was a vocal advocate of women entering the service, “his vision for women was still fairly gendered.” [9] In her oral history, Bhattacharjea was pithier still. “In those days, you expected him to be full of modern views, and in favour of bringing women out into the open,” she wrote. But that was before she faced down a prime minister who demanded to know whether her mother would come after him “with a stick” for sending her daughter to China. The experience “left a strong question mark” in her mind about Nehru’s values and policies because she “had not expected him to behave like a traditionalist.”

Traditionalist views were what Muthamma would bitterly call “the fly in the ointment.” She was to witness too many qualified women opting for the Home Services simply because their families were fearful of the ‘freedom’ that was perceived to come with the IFS.

The no-marriage rule was strictly applied for the first few years. Then, in 1958, new recruits Manorama Kochhar and Hardev Bhalla fell in love during training in Delhi. Kochhar was posted to Germany and Bhalla to Japan. Rasgotra, ever the literary stylist, wrote that the two “stoically bore the pangs of separation, hoping for divine intervention to reward their penance with the myriad delights of daily intimacies of married life.”

When Lakshmi Menon, then deputy Minister of State in the MEA, arrived in Prague in 1961, Bhalla pleaded his case to her. On Menon’s advice, Kochhar wrote a letter to Nehru requesting permission to marry Bhalla without losing her place in the Service. Nehru agreed, but it was yet another example of the many layers that women had to negotiate.

IFS officers were also not allowed to marry ‘foreigners,’ but exceptions cropped up here, too. On his first posting to Rangoon in 1950, K.R. Narayanan met and fell in love with Daw Tint Tint, a Burmese woman. Narayanan returned to Delhi, sought––and received––Nehru’s permission to marry Tint Tint, who would adopt her new husband’s country and become better known as Usha Narayanan, eventual First Lady of India. [10] Narayanan’s case led to Nehru instructing the MEA to be sympathetic towards applications by officers to marry nationals of neighbouring and friendly countries, at the very least.

But apart from instances of Nehru’s personal intervention, the rules remained firm. Women could not marry as long as they were in the IFS. And if, as in the case of Surjit Mansingh, they fell in love with Americans, that was the end of their career. Mansingh, who served between 1959 and 1965, quit the service to marry Charles Heimsath. After her return from Beijing in 1960, Mira Sinha Bhattacharjea also resigned from the Service to get married. [11] The rules forbidding marriage would remain in place until 1973.

Everyday indignities continued. A few years into service, Muthamma encountered the Chairman of the UPSC who had interviewed her in 1949. Now retired, the man told Muthamma that he had used his credentials to push the rest of the board to give her a minimum passing mark during her interviews in 1949. It was yet another slight.

In 1970, Muthamma was posted as India’s first woman ambassador to Hungary––a designation she received much later than her male counterparts. The rules were designed to trip a woman up if she wasn’t careful. For instance, one of them said that a single Head of Mission could take a close female relative at government expense as hostess. “I was refused permission to take my mother with me, since the rules referred to a ‘he’, not a ‘she,’” Muthamma wrote.

All this culminated in her filing a case before the Supreme Court, alleging discrimination. [12] When the Government of India heard that Muthamma was deadly serious about taking it to court, she was hastily promoted as India’s ambassador to the Netherlands. The matter was adjourned several times before it was finally heard by a three-judge bench headed by Justice Krishna Iyer. [13] Given that she had been promoted already, the case was dismissed. The kicker lay in Justice Krishna Iyer’s closing statement, “We dismiss the petition,” he wrote, “but not the problem.”

Pioneers

hen Muthamma’s case went to court in 1979, former Foreign Secretary and Ambassador Nirupama Menon Rao was a young officer in the Ministry of External Affairs. “We were witness to the manner in which the bastion of male prejudice against women officers came tumbling down,” she told me in an email interview. “It was a giant leap forward for women in the service.”

The IFS had the reputation of an elite corps from the days of its inception. The induction of women, it was said, was a progressive—even a feminist—step forward. Muthamma’s trajectory was representative of what a woman could achieve in independent India. But it is also a testimony of how limited that achievement could be, and how easily it could be erased.

“While it is easy to trace a Pandit or a Mehta, it is a task to trace Hamid Ali. We also have to ask who these women are, and why they’re being left out.”

Khushi Singh Rathore’s research is marked by this erasure. “Muthamma was an extremely important figure, but there were also Hansa Mehta, Lakshmi Menon, Begum Shareefah Hamid Ali, to name a few,” Rathore said. “While it is easy to trace a Pandit or a Mehta, it is a task to trace Hamid Ali. So where are the women is just the beginning. We also have to ask who these women are, and why they’re being left out.”

A look back across the history of women’s public and political participation in India reveals a range of barriers, from respectability to perception and patriarchy. Individual stories are a microcosm of the complex struggles that women in Indian diplomacy have faced through the decades. None of the women who cleared the IFS examinations were token representatives. Every one of them had a vision for how she wanted India to grow.

The women were only the most visible outsiders in what Rathore frankly calls the “old boys’ club” of the foreign service. Caste and class, along with gender, deeply influenced recruitment. The stories of diplomats who confronted these glass ceilings have usually been told quietly, or not at all. Sometimes, like in Muthamma’s case, they create an explosion.

Muthamma’s petition shook the establishment from the top downwards. It may well have been the reason why she was never made Foreign Secretary. “As I was once told by a senior male diplomat,” Rathore said, “the reason she was probably not appointed Foreign Secretary, despite being deserving, was because she was too outspoken for the liking of the political leadership.”

Getting both into and ahead in diplomacy continues to depend on gendered networks and enduring institutional biases. [14] “The glass ceilings have been broken, although the glass cliffs may still exist!” Menon Rao wrote to me. “Women are still on test.” The numbers tell an alarming story. As of October 2020, out of a total service strength of 815 IFS officers, there are only 176 women officers. Of these, only 19 are presently Heads of Mission; that is, Ambassadors or High Commissioners.

In a webinar organised by the Indian Council of World Affairs in October last year, Menon Rao said, “The numbers are still small—as a proportion of the overall strength of the Service and as a proportion of the senior leadership positions.” Rathore suggested that we may have actually taken a few steps backwards. “We had such a tremendous leadership of women in the struggle for independence,” she said. “Women not having an equal place at the diplomatic table in the aftermath of independence and in the foreign policy apparatus of independent India is, to me, going backward rather than forward in time.”

Since Chokila Iyer became the first female foreign secretary of India in 2001, two women have followed in her footsteps: Menon Rao (2009-2011) and Sujatha Singh (2013-2015). Change is coming slowly. Economist Shamika Ravi recently noted that 42% of trainees in the freshly graduated 2020 batch were women. Between 2014 and 2019, Sushma Swaraj served as the Minister of External Affairs in the first term of Prime Minister Narendra Modi's government. “It would be unfair to dismiss the change that has happened so far,” Rathore said. “That would discredit the work of women who worked hard to push for inclusion. But—and it’s a big but here—is better equivalent to enough? I don’t think so.”

“We do not yet know the accounts of women officers, along with Muthamma,” Rathore told me. “I think that’s a good place to start digging. We cannot stop at the first woman.” That first woman, fearless fighter of the status quo, would have agreed.

Narayani Basu is a historian and author, most recently of V.P. Menon: The Unsung Architect of Modern India.