In March 1957, just before dust-ridden searing heat enveloped his city, the Maharaja of Bharatpur hosted an American travel writer named Jack Denton Scott. On the second day of the visit, there was a grand dinner. A livery of turbaned bearers appeared in neat choreography, carrying platters of duck meat, spices, honey and herbs. The maharaja chose the best ingredients and placed them in an imported pressure cooker.

The party retired for the day after a hearty meal. But Scott stayed on with Indu, as the maharaja was known to friends. They sat on the cushioned floor listening to filigreed ragas played by a royal troupe. As the night wore on, the conversation ranged over ‘the state of the world, communism, caste, the Gita, sex, yoga, the future of India,’ and the Shah of Iran’s impending divorce. Once in a while, Scott would look up at the bats on the high ceiling—they appeared to be swirling too. When dawn trickled in, the marble walls of Moti Mahal glowed in soft light.

Scott and his wife were in India for an activity that is now banned in the country: shikar, or hunting. They’d been to the forests of Hoshangabad in Madhya Pradesh before coming to Rajasthan, where they had successfully bagged a leopard, some peacocks, jungle fowl, black bucks, wild boars and more. The ducks served at Indu’s feast were hunted at Keola Dev Ghana. On the last leg of their trip in Mysore, the Scotts even shot down a mighty gaur from the back of an elephant.

This was all at the invitation of the Indian government. Hunting brought in much-needed foreign exchange and helped the country to cement relations with global sophisticates, the main clients for commercial shikar. The excursions proper were conducted by elite, often blue-blooded, men who ensured their guests didn’t really have to rough it out.

Scott published a book about his hunts, Forests of the Night, in 1959. But, in about a decade’s time, it turned into a description of a vanished world. Shikar companies had to shut shop by 1971 when a litany of laws were passed to protect endangered animals. (Keola Dev Ghana became the Bharatpur Bird Sanctuary.) This marked the end of a strange chapter in the country’s history, when India served up its wildlife to westerners who wanted to live out their fantasy of a Corbett-esque adventure.

Even the switch to top-down conservation in the 1970s has a contentious legacy, for it adversely impacted communities that lived in and around the forest. But in the early years, the camera had not quite replaced the gun, and men like Tootoo Imam took pride in their role as “brown hunters.”

Fin de Siècle

ugustien Imam was born in 1920, with a silver spoon and all. His mother traced her lineage to the French aristocracy that settled in Pondicherry after the Napoleonic Wars; his father was a well-known barrister in Patna who had presided over the 1918 session of the Indian National Congress. His parents visited Cairo around the time when Howard Carter discovered Tutankhamun’s tomb. The ruins of ancient Egypt left such an impression on them that they nicknamed their toddler ‘Tootoo.’

Tootoo was home-schooled by an Austrian tutor and did not go to college. It would not have been simple for him to establish a career in the conventional sense. He also had a fraught relationship with his step siblings. So when her husband died in the 1930s, Nattie, Tootoo’s mother, sold some of the family’s land to purchase mica mines in Jharkhand.

All of 19, and newly married, Augustien moved to the forested pockets of Kodarma to manage this estate. But, soon enough, the industry slumped. After that, he tried his hand at a succession of ventures: lumbering, life insurance and even car racing. He made a name for himself in the swish circles of his time by winning the Calcutta Grand Prix thrice.

In the years to come, he would leverage these contacts for shikar. He organised escapades for his friends at the Marwateri Basin near his new residence in Hazaribagh. The watering hole had a protruding ledge from where one could survey the wildlife, which was so abundant that Imam jokingly called Marwateri his ‘tiger farm.’

Frequent visitors included Rajkumar Gautam Narayan of Cooch Behar, uncle of the international celebrity Gayatri Devi, and Maharaja Jai Singh of Jaipur, her step son. The head of the Indian Mining Association also came often with his wife. Evenings at Tootoo’s were full of bonhomie and the merry clink of crystal. “Those were different times,” Alfred Hasan ‘Bulu’ Imam, Augustien’s son, told me over a call one evening in March last year.

But a growing insecurity plagued this revelry. Around the time of independence, the landed class, the chief beneficiaries of the colonial system, had to cede many of their assets to the newly-formed Indian state. They were not impoverished, but had to look for new ways to fund the extravagant lifestyles they were accustomed to. (The Maharaja of Rewa, for instance, sold white tigers from the breeding grounds of his palace to select clients.)

Augustien Imam decided it would be wise to monetise his hobby. Upon the suggestion of the Washington realtor and attorney Ralph Scott, he set up his own company in 1962. It was called Wild Sports of India, and sold shikar.

A Good Game Can Win Hearts

y the early 1960s, Allwyn Cooper Private Limited, India’s biggest hunting outfitter, was already offering the following deals:

- Fur and Feather. For $4800, clients could shoot two dozen water or jungle fowl, and a tiger. (The tiger could be swapped for any other animal.) For an additional charge, a beat [1] was available.

- Fur and Fang. Two animals of the guest’s liking for $6500.

- Trophy Room Special. For $25,000: A tiger; forest panther; sloth bear; gaur; water buffalo; bush boar; river crocodile; sambhur, cheetal, hog, swamp and barking deer; four-horned buck; chinkara; black buck; nilgai; two mouse deer; a dozen hares; and assorted water and jungle fowl.

Wildlife protection and hunting regulations were left to states, but shikar agents were accredited by the Union. The Ministry of Transport oversaw all matters related to tourism, and ran a tight ship. Western-style hotels were required to use fabrics with typical Indian patterns, and Delhi’s Ashok Hotel even got a rap on the knuckles for importing crockery in 1955.

But no such directives were issued for shikar companies, whose clientele were immensely influential. Imam’s guests included Count Cinzano, the vintner; Dr. Rivetti, the Vatican’s clothier; Dr. Camille Malo of Normandy, a famous eye surgeon; and Robert Lansing Phipps, whose stepfather Marshall Field was the force behind the Field Museum of Natural History in Chicago. Still young, India wanted to charm these powerful men, knowing how a good game could win hearts.

Hunting diplomacy was not without precedent on the subcontinent. In colonial India, princes hosted lavish hunts to exercise their soft power and curry favour with the British. Their hunting grounds were coveted, because certain animals like the lion and wild ass had become scarce in British-administered forests.

So the landed gentry protected its tracts in a systematic, and sometimes, zealous way. Colonel Kesri Singh of Jaipur, for instance, implanted iron hooks in his reserves to injure trespassers. His guards were told to kill violators on sight. Indigenous communities were coerced out of wooded lands where big game was abundant. With their presence erased, by the twentieth century, shikar became a gentrified pursuit in the English imagination, complete with elaborate codes of conduct and pageantry.

Meaningfully, this impression was quite different from the one created for another part of the British empire—Africa. This continent was thought of as dark and untamed, a terra incognita where rugged men of the world came to script their pluckiest adventures. But by the 1940s, all this changed, when anti-colonial movements picked up steam. Africa became relatively unsafe for the guided hunt, and wealthy westerners turned elsewhere.

‘Soft, assured English’

n the 1950s, India’s Tourist Division commissioned Ellis Dungan to create a documentary on shikar. After his first innings in Tamil cinema, this Irish-born American director returned for The Jungle (1952). The film was shot entirely on location in Yercaud and Hogenakkal, with a mega-sequence on wild elephants running amok.

Dungan went on to serve as an advisor on India’s outdoors to Hollywood studios, which were churning out exotic adventures by the dozen. MGM, Universal, and 20th Century Fox produced films like Harry Black and the Tiger (1958), The Big Hunt (1959), and Tarzan Goes to India (1962). Dungan’s documentary Tiger Shikar in India (1955) too, was well-received. (In fact, it outlived the hunting ban of 1971: the government repositioned it as an example of Indian culture and screened it with narratives on Chandigarh; khedda operations; [2] and Kashmir.) [3]

When six gesticulating porters appeared to take his bags, Scott felt as if he had “kicked over a human anthill and the swarm was upon him.”

It’s unsurprising that India took the film route. After independence, the Ministry of Transport splashed out on publicity to grow its market. It coordinated with the External Affairs, Information and Broadcasting, and Finance ministries to create annual plans for advertising and promotion. All tourist literature was centrally produced and distributed through a broad network of offices, which by 1956 included five international bureaux, in New York, London, Sydney, Paris, and Colombo.

The government treated every piece of external communication as an opportunity to project the right image of the country: scenic, syncretic—and modern. Details of the Bhakra-Nangal Dam were included in various materials, and culture guides were trained to tell tourists about India’s Five Year Plans. The competition was fierce so countries had to think up innovative ways of promoting their tourist offering.

India’s Tourist Office in New York employed the mid-century form of influencer marketing. In 1957, it invited Jack Denton Scott to write about the country’s hospitality. His itinerary was so closely planned that from the time Scott and his wife flew into Calcutta, they were not left unattended.

Scott was daunted by Dum Dum Airport. When six gesticulating porters appeared to take his bags, he felt as if he had “kicked over a human anthill and the swarm was upon him.” Another tug of war started between the beggar children who grabbed his coat sleeve and lapel. But then the mayhem dissipated: Jeeves-like, the “courtly” Colonel M.D. Framjee arrived and took charge of the situation in his “soft, assured English.”

This kind of hospitality was crucial to the hunting industry, especially as a new kind of tourist emerged. Shikar had become extremely popular with wealthy Americans who had benefited from the economic boom of the post-war years. As the rich got richer, they travelled around the world to collect hunting trophies as status markers. The rarer, the better.

No one understood this better than Augustien Imam, who devised the perfect sport for such clients: hunting man-eaters.

‘Vindictive, conceited brutes’

rom 1959, an old male tiger had wreaked havoc in the eastern ghats of Orissa. The Statesman reported that seven villages had been evacuated in six years due to this terror. In 1965, the authorities called on Tootoo Imam to hunt down the menace.

Imam agreed, and worked through May and June to gather information about the tiger’s range and temperament. It quickly became evident that this man-eater had curious habits. On several occasions, he had spared his victims after pinning them down. There was also some indication that he suffered from an itchy stomach—he’d rub his belly against broken saplings. Imam gathered these insights, but couldn’t make the capture. So another trip was planned for winter. This time, he brought along guests: Ed and Alida Sverdsten, a sexagenarian couple from Idaho.

Imam prepared 11 beats in Chelagada Valley. A bait or two were placed at each site. It was a staggeringly costly operation. The man-eater killed nine more people the two months before Alida Sverdsten finally shot it dead on 2 January 1966.

The tiger’s victims were skint labourers who had set up huts in the podas—fields—at harvest time. As a young man, Bulu Imam wrote about them in a poem:

Besides a swaying jana crop

And within the shadowed bamboo place,

We found a cloth, an empty pocket splotch’d

With blood. And then, as if to add

A finger to the heart…

A knot of hair, and a crushed packet

Without matches.

Empty.

‘A magnificent outlay’

t least one publication described man-eaters as “vindictive, conceited brutes” to arc the plot up to a thrilling shikar. But the truth is that by the 1950s, hunting was not as daring as it used to be. With advancements in ammunition, transport, and amenities, it was easy to shoot a stunned animal by the headlight of a car at night.

Looking back, it’s clear that the blandishments went well beyond the thrill of the chase. For a hunt in Assam, Hollywood director John Huston and his friends were hosted by the Maharaja of Cooch Behar’s Himalayan Shikar Syndicate. Their camp, Parbati, consisted of four big luxury tents, an open-air bar, and a wooden dining room on stilts. In the February 1956 issue of Sports Illustrated, Huston wrote that “the private baths were always hot, the clothes were always laundered…and there was ice in the drinks put into our hands.”

“We offered a magnificent outlay,” Bulu Imam told me. “My father even considered taking our grand piano on camps, but didn’t.” Such lavish excursions depended on a large retinue of labour including cooks, drivers, mechanics, gun bearers, and trackers. Depending on the hunting method, an additional 75 to 100 people from the neighbouring villages would be employed on a day-basis as beaters. The entire team was managed by a lead shikari.

The set-up owed something to Africa, where it was standard practice to employ “white hunters” on safaris for the elite. White hunters were typically sportsmen who knew the game lands well. They interpreted animal behaviour and gave shooting tips to clients. Most importantly, they would translate the local language and customs for the hunting party. This was reassuring, to be guided by an ethnic compatriot. Put another way: they did what Westerners would not trust Africans to do.

This sense of shared identity was advantageous in other ways too. White hunters could entertain their guests by campfire. There was no need for hierarchy in communication: they felt at home with the statesmen and stars they hosted, swapping jokes, stories and arguments well into the night. Over time, these men became minor celebrities in their own right. R.J. Cunninghame, Philip Percival, and Bror von Blixen were well-known for guiding public figures like Theodore Roosevelt, Ernest Hemingway, and the Prince of Wales to name a few.

“We offered a magnificent outlay. My father even considered taking our grand piano on camps, but didn’t.”

Augustien Imam drew on this legacy and called himself a ‘brown hunter.’ “Other shikar companies left ground operations to their staff, who did not have the cultural capital to entertain and talk to their guests as equals,” Bulu Imam told me. “They did not have the same élan as white hunters. My father was an exception.”

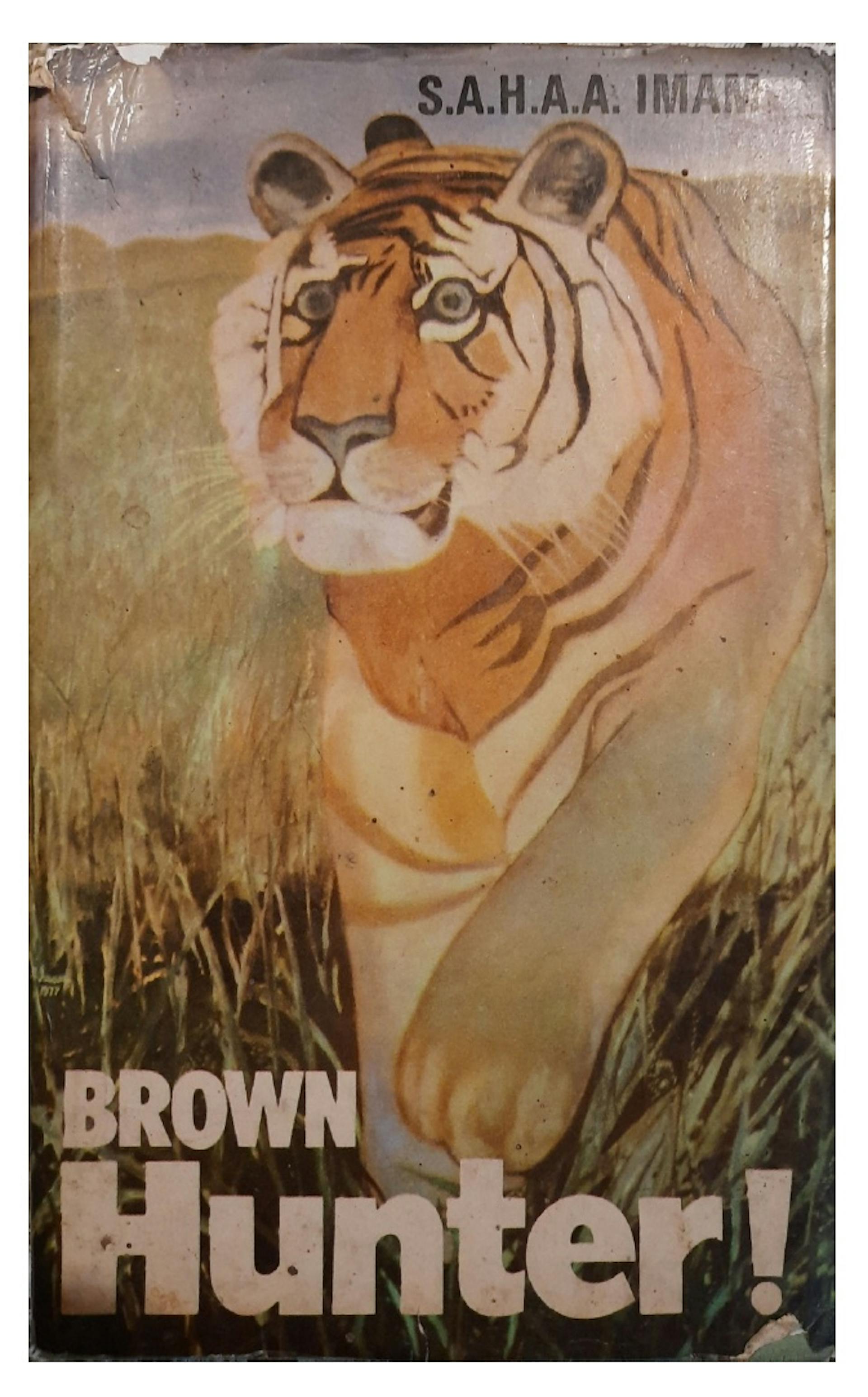

The cover of Augustein Imam’s hunting memoir Picture Courtesy: Bulu Imam

Take Rao Naidu, for instance. He was the head shikari for Allwyn Cooper and accompanied the Scotts on their hunt in Hoshangabad. Naidu came from a modest background. He had studied engineering before pursuing a career in hunting tourism. He was exceptional at his job. He introduced his guests to Gond and Korku culture and could speak Bundeli, the principal dialect of the region. He was successful enough to eventually start his own shikar company.

But the Scotts, perhaps unwittingly, patronised him. Naidu’s English, “was not of the Oxford variety but it was good,” Scott wrote in Forests of the Night. “Vastly, he pronounced ‘vostly’ and occasionally he stumbled over a word like ‘acknowledgement’ but largely his vocabulary was superior to Americans including me.”

There were barriers in catering to guests from another milieu. We know that Naidu invisibilised the caste system in trying to convince the Scotts that India had broken away from blind faith and tradition. He called it an “outmoded” practice when, in fact, discrimination existed within his own ranks. The skinner [4] of the camp, Chhotelal, was from a caste formerly designated untouchable. The dak bungalow, where the hunting party stayed, lacked toilets. It fell on a Mehtar [5] worker to pick up night soil.

J’Accuse

n the early 1970s, Prime Minister Indira Gandhi’s government passed two laws that marked the end of shikar. By this time, certain key species like the tiger, crocodile, and rhino had been pushed to the brink of extinction by global trade in addition to hunting. Animals were captured and exported to international zoos, circuses, and laboratories at an extensive scale. (In 1959, a dealer would pay $5 for a peacock that would be further sold for about $150 in the US or England.) The country had also lost large swathes of forest cover to the Grow More Food campaign: cropland increased by eight million hectares per decade between 1950 to 1970. [6]

Wildlife was also indiscriminately killed for fashion and lifestyle products. Kailash Sankhala, an Indian Forest Service officer who would later become the first head of Project Tiger, conducted a covert study on the fur industry in the markets of Delhi. His friend would pose as a prospective buyer and enquire about prices. The results were shocking: shops stocked anywhere from 1000 to 3000 leopard skins annually.

In a bid to raise awareness, Sankhala published his findings on the front page of the Indian Express. He also authored a series on the lives of the tigers in Delhi’s National Zoological Park. The international and domestic outcry culminated in the government’s ban on tiger hunting in 1970.

Some hunting companies moved court to secure their right to livelihood, but in vain. Augustien Imam also wrote an open letter to Indira Gandhi titled ‘J’Accuse.’ He felt that the new legislation did not account for the socio-economic realities of conservation. It was “a narrower outlook to save wildlife with zeal, money, and legislation” without considering the challenges of those who lived in and around forests.

Conservation-by-fiat was foredoomed, he argued: people would covertly kill tigers to defend their cattle and kin if they were not guaranteed protection against man-eaters. In Cheetal, the Wildlife Preservation Society of India’s journal, these arguments were dismissed by Sankhala as “false claims.”

All shikar companies had to shut shop in a year’s time. Many hunters felt rudderless after they lost their jobs; they did not have alternative skills to rebuild their lives. Some, like Ajaikumar Reddy, who worked on a contract basis with Allwyn Cooper, tried their hand at writing. Bulu Imam, too, wrote about his father’s exploits—in Hindi and English—for publications like Sports Afield, Satya Katha, and Manohar Kahaniya.

Aristocrats of the ‘brown hunter’ class received another body blow in 1971. That year, Indira Gandhi abolished the privy purses they had been receiving from the government. “This meant that our families were left with zero income,” Saad bin Jung told me. He traces his lineage to the royal families of Bhopal, Pataudi and Hyderabad. “Many rulers sold their land and jewellery to make ends meet. They found themselves in court, fighting over property. Primogeniture was no longer applicable, so each one had to vie for their own pound of flesh,” Jung added.

Jung and his wife decided to rebuild their lives under the placid gaze of the Nilgiris in Karnataka’s Bandipur region. They set up their first ecotourism lodge in 1988, but had to pull out of business when the surrounding forests came under the stronghold of the sandalwood smuggler Veerappan. Jung has since moved to Tanzania and runs the Royal Migration Camp at Serengeti National Park. The camp’s interiors are fitted with period furniture from the wildlife reserves of his ancestral Bhopal. “I have dedicated my life to recreating this bygone era for my progeny,” he said.

The Family Silver

he year 1971 was also pivotal in another way. In September, Indira Gandhi called for a small meeting in her office. She was concerned about the declining rate of biodiversity in the country. The attendees were Karan Singh, chairman of the Indian Board for Wildlife; Kailash Sankhala; conservationist ‘Billy’ Arjan Singh; bureaucrat M.K. Ranjitsinh; and Anne Wright, who had once frequented the hunting parties at Imam’s with her husband, then head of the Mining Association of India. Wright had turned a new leaf since and joined the World Wildlife Fund.

After some discussion, it was decided that Gandhi would write to the states to move the subject of wildlife to the Concurrent List, so that the Union could introduce a law on the matter. This paved the way for the Wildlife Protection Act of 1972, which provided a legal framework for the creation of national parks and sanctuaries.

Ranjitsinh was a key architect of the law. While drafting it, he referred to the conservation policies of countries like Kenya, Indonesia and New Zealand. He was also inspired by America’s land management practices that were propagated through NGOs like the International Union for Conservation of Nature (IUCN). These were varied influences, but he finally opted for a stringent approach to reserve design. All national parks were required to have an inviolate core zone, where flora and fauna could flourish undisturbed by human interference.

The breaking point was the Sariska fiasco. In 2005, the reserve was famously wiped clean by poachers, while authorities kept fudging numbers to cover up.

A year afterwards, the government launched Project Tiger in nine reserves. The point was to provide the endangered cat with a safe home range where it could naturally procreate. In a decade’s time, India’s tiger population grew from just over 1800 to about 4000. Encouraged by this success, protected areas were established for other animals too, at such a scale that, by the end of the twentieth century, five percent of the country’s total land was controlled by state forest departments.

But this top-down approach was riddled with injustice. People were forcefully evicted from forests to establish national parks. They were often given inferior land and housing on the fringes of the core zone. Whole communities were pushed into cycles of debt, alcoholism and domestic violence because of this traumatic dispossession. Those who stayed back in the forests were cut off from healthcare, education, and utilities, because no development was allowed within protected areas. [7]

It was a disaster that spiralled over decades, until the system nearly collapsed. The breaking point, in a way, was the Sariska fiasco. In 2005, Sariska Tiger Reserve was famously wiped clean by poachers, while authorities kept fudging numbers to cover up. An independent task force was set up to evaluate the debacle. The team made field visits and had several rounds of consultation with a range of stakeholders, from tribal activists to researchers. Its final report opened with a definitive statement:

‘The protection of the tiger is inseparable from the protection of the forests it roams in. But the protection of these forests is itself inseparable from the fortunes of people who inhabit these areas.”

The task force recognised people’s rights and welfare as an important component of conservation. It warned against the unchecked growth of high-end hotels in eco-sensitive zones: “The virtual takeover of protected areas by luxury tourism would open fresh wounds in the yet-to-heal conflict between parks and people.” The report also made a strong case for repatriation, where revenue from the hotel industry could be channelled back to the protected areas.

This vision remained unfulfilled, even though wildlife holidays became increasingly popular with the Indian middle class after liberalisation in the early 1990s. Tourist traffic varied across sites but one gets an idea of the growing demand for safaris from the fact that almost 13 lakh people visited 22 tiger reserves in 2004-05.

This made for good business. In a study on nature tourism published in 2010, conservationist Krithi Karanth and environmental geographer Ruth DeFries noted how some tourist establishments had a limited understanding of their impact on the environment. Resorts in the arid region of Ranthambore, for instance, had swimming pools and fountains. Only a few miles away, inside the reserve, the forest department had to artificially supplement the water bodies for the sake of wildlife.

Hospitality also didn’t contribute to employment generation as hoped. Luxury businesses recruited local people in lower positions—for gardening, laundry, housekeeping and so on—while managerial posts were given to outsiders.

Today, these hierarchies exist even on the demand side of the safari ecosystem. Most visitors travel on a tight budget, taking limited rides into the forest, in buses, canters or small cars. The guides assigned to these vehicles by the forest department cater to the group en masse. There’s no personalised commentary.

Compare this to the upper crust. Boutique lodges use modified open jeeps for their safaris, where the seats are arranged in ascending height to provide a better view of the forest to all passengers. The lodges also employ naturalists to look after their well-heeled guests. These naturalists use humour and storytelling to explain the forest and evoke awe.

Each safari ride comes together as an anthology: interconnections are painstakingly explained; bird species are compared to their cousins; reference guides are ready at hand. It’s not completely removed from the experience of having a white hunter at your service.

The deluxe safari, borrowing from the African model, has come of age in the last few decades, even as it continues to negotiate a deeper, existential threat. Development projects are steadily eating into forest land, which stokes the ire of those like Bulu Imam. “The forest is like your family’s silver,” he said. “Would you sell or save it?”

“With shikar, animals at least had market value,” he told me. “People protected the forests if only for selfish reasons—if only for game.”

Niyoshi Shah is a researcher and writer from Mumbai, with varied interests. In the past, she has worked on projects related to public and mental health, new technologies, and design history to name a few.