An elephant capture is a tense operation. I was part of one in June last year, in my role as programme coordinator with the Nature Conservation Foundation in Karnataka’s Hassan district. The forest department had ordered this capture after a tuskless bull had developed a penchant for wandering into villages near the town of Sakleshpur in search of food. There were broken walls and shattered windows. Locals were living under a pall of fear, and they wanted it to end.

On the day of the capture, captive elephants from neighbouring elephant camps had been driven into Sakleshpur. A veterinary team from the Bhadra Tiger Reserve walked ahead with them, while our team from the NCF followed on foot. The vets’ job was to tranquilise the animal, after which forest department personnel would tie one end of massive ropes around the fallen elephant’s legs and the other around the necks and shoulders of the captive elephants.

After waiting at the entrance to the coffee estate for over an hour, I received word that the bull was down and could be approached safely. It felt surreal, at first, touching the many folds and wrinkles of a wild elephant’s skin. The vet team administered an antidote to the bull so that he could be woken up and dragged away by the captives to a spot where members of the Wildlife Institute of India fitted a radio collar along his neck. It took nearly two hours to drag him over a distance of less than 500m. Then, the hapless bull was lifted by a crane and lowered into the back of the lorry, where he was further secured with girders to prevent an escape during transit.

He was released in Nagarhole Tiger Reserve, more than 200km away. Over the next month, we followed his movements with the help of the tracker in his collar. He’d started making his way up north, crossing tiger reserve boundaries and gravitating towards human settlements. At one point, he wandered into Somwarpet, a major town in Kodagu, and damaged a government building. Exactly a month after we relocated him, the elephant was back in his home range on the outskirts of Kodlipet town, some 20km from where he was captured.

Death in the Fields

uman-elephant conflict is a relatively new problem in Hassan. Many villagers I spoke to over the course of my six-month stint in the field said that they hadn’t seen an elephant in these parts before the early 2010s. The influx, I learnt, was the result of a mix of complex factors including deforestation, changing land use patterns and the behavioural ecology of elephants.

The tuskless bull’s return to Hassan district via Kodagu, for instance, wasn’t surprising—elephants are generalist species that use large areas for their home regions. There are anecdotal reports of some individuals using as much as 2500 sq. km in various parts of the country. The vacuum created by the removal of individuals from one area potentially attracts less dominant individuals from others.

But both forest authorities and conservation NGOs have learnt some of these lessons the hard way. Earlier, the conflict management strategy was almost entirely capture-based. It even seemed to work for a period. For four-odd years between 2014 and 2018, there was relative peace in Hassan. But, gradually, an influx of over 40 new elephants from the neighbouring districts of Kodagu and Chikmagalur was reported. Today, there are over 70 elephants in Hassan district—some 15 of them are considered to be seasonal visitors.

Only 12.33 percent of Hassan’s land cover is forest area, compared to 47.87 percent in Kodagu and 42.49 percent in Chikmagalur. [1] The landscape in all three districts is a patchwork of subsistence crop fields, massive commercial crop plantations and reserved forest area. It is often hard to tell where one type of land use ends and another begins. All of it is now elephant territory.

The Nature Conservation Foundation had established the Asian Elephant Project in Hassan in 2015, after successfully implementing the same measures in Valparai, Tamil Nadu under the leadership of Dr. Ananda Kumar. My duties included overseeing the project’s Early Warning System that notified locals of elephant proximity via SMS alerts, LED display boards and alert beacons at junctions. I also spent a lot of time interacting with locals about their elephant-related concerns.

In the six months I spent in Hassan, I recorded over 40 incidents of conflict. (There were many more that went unreported.) Field days were gruelling. We spent hours trekking silently amongst coffee and areca plantations, fragments of forest and large swathes of paddy fields, all to hear the snap of a branch or a rustle of leaves indicating the presence of an elephant. Three weeks after I joined the team in July, the monsoon hit with full force: the mist and slush made a hard task more frustrating.

We spent hours trekking silently amongst coffee and areca plantations, fragments of forest and large swathes of paddy fields, all to hear the snap of a branch or a rustle of leaves.

What is at stake in Hassan and elsewhere is weeks, months and even years of agricultural effort. When elephants damage crops, the financial and emotional strain on farmer families can be too much to bear. This stress on livelihood leads to a situation where something even more precious is staked: life itself. In the last decade, there have been more than 80 human deaths and around 50 elephant fatalities in Hassan district. [2]

In June last year, a landowner shot an elephant in Gurgihalli, a village near Belur town. The weapon was a 12-gauge shotgun. Our team reached the site the next morning to ascertain what had happened. Officials of the forest department scurried about, taking pictures of the corpse and trying to complete a post-mortem before the stench became unbearable. In the course of the day, they found roughly 10 pellets in the elephant’s brain cavity.

Our initial recce and my conversation with forest department officials indicated that the farmer meant to shoot over the elephant’s head, but got too close to it instead. Even now, the general sentiment amongst some farmers is that they are willing to accept hefty fines and jail terms that can last over five years, rather than have an elephant destroy a painstakingly nurtured field.

Three months later, I was in close quarters of the reverse situation: a human death. Unknown to an elderly farmer, who was walking to his field with his cattle in Sullakki village, two tuskers were on the same road, looking for fresh paddy to feast on. Some villagers who reached the spot first told me that the way the mud on the ground was pressed indicated that the tusker had picked up the farmer and flung him almost 20ft away.

From his injuries, they guessed that the elephant had used his tusks to stab the farmer repeatedly. That morning, the victim’s family and some political outfits did not allow the police to conduct an initial post-mortem, insisting that higher authorities from Hassan show up and listen to their woes. They compromised only after the deputy commissioner arrived at the scene.

Planter Punched

The situation has gotten so bad that they’ve started feeding on coffee beans,” said B.S. Rohit, a coffee planter in the Hassan region. “Can you imagine that? Elephants eating coffee?” Rohit is a fifth-generation planter and an active member of various associations—such as the Hassan District Planters Association—that meet frequently to deal with the human-elephant conflict situation.

“Each tree on a coffee estate takes roughly eight years to start providing a yield,” Rohit explained. “People have trees that have grown over 30 years, so the loss is insurmountable, really. Hiring labour has also become a problem because, understandably, no one wants to venture into the estates.”

More prosperous planters like Rohit can cope with the losses, but it’s much harder for marginalised farmers. I’ve come across entire fields that have been trampled upon by elephants. In 2022, Rohit shared, most farmers had decided not to plant paddy for peace of mind.

In the course of my work, I got to know Ramachandra, a farmer who owned a smaller patch of land close to our field station in Kenchammana Hoskote. His house and estate were nestled between two patches of forest connecting villages, an ideal elephant corridor. Ramachandra would call us routinely, keen to gather any information we had about the elephants’ movement patterns for the day.

On one occasion, a tusker had topped a fishtail palm tree on Ramachandra’s property at night, feasted on it and then ostensibly left. An initial recce suggested no sound or smell (elephants have a “greenish” smell to them, similar to cow dung but earthier and instantly identifiable in a forest), but an hour’s waiting betrayed his presence in a bamboo thicket, where I heard him snapping branches. Elephants are often depicted as clumsy and bumbling in popular media, but they are some of the quietest animals in the wild. Ramachandra did not go to the estate that day. That evening, we sat on the verandah of his house and waited. We heard a few sounds of feeding—creaking and breaking branches—but didn’t see anything. “At least I know he’s still there,” Ramachandra told me. “Imagine if I didn’t know and I’d stepped out.”

Aaditya Kaliyanda’s father had not been so lucky. The planter was the victim of an elephant encounter in 2021. It caused Aaditya to quit his corporate job and relocate to their village of Kiruhunse to take over the estates his father managed. When I met Aaditya in November last year, he was clearly anxious about me riding back home in the dark. He told me that he gets nervous about simple tasks like sending workers into the estate. The very idea of walking around after sunset fills him with dread.

Aaditya’s fears were not overstated, as I’d found out in August last year. I was returning to the field station on my motorbike when I approached a downhill turn. I hit a blind corner, and nearly fell off as I rounded it. When I looked up, I saw the biggest tusker in the region, standing less than 50m away from me on the main road. Even in my state of shock, I noticed villagers running out of their homes to take pictures. Perhaps the commotion made the elephant pause for a moment, but that gave me enough time to restart the bike and ride back up the slope.

The drama wasn’t over yet. He took a few casual steps towards me, and then decided he’d rather sleep in the coffee estates. He walked into the verandah of a farmer’s home located on the main road, then stepped gingerly into the adjourning coffee estate. To me, the moment will always remain stretched in time, but all of this actually happened in the span of 30 seconds. Later, the villagers told me that he was a special individual. “Aa doddu aane yavathu yenu maadalla, sir.” This big elephant has never harmed a soul. He remains the only elephant in Hassan that can get away with damaging farmers’ crops. When he comes into musth—a period of heightened aggression accompanied by surging testosterone in bull elephants—he is allowed to gallivant on the main roads around the villages.

A Mammoth Task

he state government was simply not doing enough: this was the view of the majority of the planters I interacted with. “There are a lot of temporary solutions being thrown around, but nothing permanent,” Rohit told me. “Despite the fact that the Task Force declared parts of this region as an ‘elephant removal’ zone, elephants are allowed to live here and harass us every day.”

The Karnataka Elephant Task Force was established in 2012. Its members—scientists and forest department personnel—were tasked with conducting a survey in high-conflict areas and putting together a recommendation report for the Karnataka High Court. [3] The report’s focus on captures upset many in the conservation community. Two years after it was submitted, the forest department carried out a mass capture of 25 elephants in the Hassan region. Some were relocated to reserve forests or national parks, while others were sent to elephant camps in Karnataka and outside. (In recent years, based on the advice of experts, the forest department has slowly become open to the idea of favouring “conflict management” over “capture-based management.”)

The temporary solutions that Rohit referred to include erecting low to medium-voltage fences—also called solar fences—around coffee estates, and digging elephant-proof trenches that are around 5 to 10 feet deep. Some farmers use hanging-wire fences, dangling live wires off electric and other poles on their properties. Of these methods, I noticed that only the solar fences have been partially effective. The trenches would give way or fill up during monsoons, and hanging wire fences were easily broken.

The forest department has a system of ex-gratia compensation schemes but affected people have to jump many bureaucratic hoops to avail the meagre amounts. “You tell me,” Rohit said, “if you offer ₹200 for a coffee tree that took a decade to grow, does that make any sense? If a person dies, will a few lakhs cover the loss the family has to bear?” On average, Rohit said, the department took two to three years to process a claim.

If you offer ₹200 for a coffee tree that took a decade to grow, does that make any sense?

Capture might be scientifically and practically unsound in many cases, but locals tend to demand it. Local MLAs often lead large protests in the wake of a human death. “This entire situation turns into a political game, especially when elections are around the corner,” Aaditya told me. “The government has not approached me even once after dad’s death, not even to offer condolences. I don’t expect them to do an iota of work.”

“People expect us to relocate all 70 elephants, despite seeing that it hadn’t worked in June last year,” S.L. Shilpa, the range forest officer for Sakleshpur said. She thought a demand for a permanent solution was impractical. “We’ve been constantly monitoring the elephants and also responding immediately to conflict incidents to record compensation claims. But people often don’t respond to our daily alerts, choosing to deal with elephants in their own way. Yes, many people are appreciative of the department and the NCF for the alerts. But, by and large, a permanent solution is the only thing in the minds of the people here.”

The most recent human death occurred in November of last year. The victim was a 32-year-old farmer in Hebbanahalli village. A month later, after many protests and meetings with local government bodies, Karnataka’s chief minister Basavaraj Bommai promised to double the compensation amount from ₹7 lakh to ₹15 lakh, and committed to similarly improve the quantum of compensation for crop damages. The planters, in their meetings, had also suggested dividing solutions as temporary and permanent. The temporary measures brought up included radio-collaring many more elephants, and providing higher subsidies for the solar fences. They also wanted the government to avoid granting permission for large-scale infrastructure projects that could cause further displacement of elephants.

Rohit was still bullish on the idea of translocation. “I know that translocation hasn’t worked in the past,” he said, “but now that they’re constructing the new barricade, we should hopefully see less of an influx.” He was referring to the massive 5km railway barricade being constructed between Hassan and Kodagu, along parts of the Gorur backwaters. When fully constructed, this iron fence will be five to six feet tall. But already, some elephants had managed to cross the unfinished barricade, and have since shown no signs of moving back. Once they are relocated, Rohit hoped, they won’t be able to cross over again.

Feet on the Ground

lanters are not the only ones who have a bone to pick with the government. Members of the Rapid Response Team, the Karnataka Forest Department’s feet on the ground, haven’t been paid for months. The RRT is constituted by locals who are well-versed with the landscape. They have to be early risers—their job is to report elephant locations to the beat’s forest guard before the residents of the area start their days. Much of my time in the field was spent in the company of RRT members.

“We haven’t been paid for over five months,” Raju, one of the older members, told me on a rainy afternoon last year. RRT members are not directly employed with the state government: they are hired through a third-party agency on contract, earning around ₹12,000-15,000 a month. “Earlier, our old boss used to pay us out of his pocket and have us pay him back when we did get salaries,” Sachin, who used to be a farmer, told me. “But the new person doesn’t seem as helpful.”

For personnel who spend much of their time so close to mortal danger, RRT members are woefully underequipped: a single gun for protection and some rudimentary firecrackers to scare away elephants where necessary. Their torches aren’t powerful enough, and often, they don’t have extra firepower for emergencies. Some of the team members lamented the fact that they had to use two-wheelers to move around. Their gear, when I noticed it, left a lot to be desired: many of them didn’t have raincoats for the monsoon.

Shilpa, the range officer, admitted there were problems. “We have a small number of vehicles, and adequate rain gear is not provided to the RRTs despite requests,” she said. “We also have issues with timely payments from contractors to the RRT staff. An RRT’s salary is not very high, and considering they are the ones who need salaries the most, they get demotivated.”

When conflict incidents occur, RRTs are often made the scapegoats. In September last year, one of the younger men I was acquainted with was held captive in the gram panchayat office in Arehalli, Belur for over a day by irate villagers who had lost paddy to a marauding elephant. They were demanding the in-person appearance of Belur’s Range Officer, so that they could show him the extent of the damages.

In November last year, there was a bit of an organisational reshuffle. Members from the RRTs were pulled into a new state-wide Elephant Task Force, where they were now shuffled between day and night shifts without warning. Several people told me that they’d rather go back to their previous rank. “First, we had no money and had to work whole days,” Sachin said, “Now, we have no money and they’re putting us on a night shift as well.”

Passing the Message

met Vinod Krishnan in September 2021. A commerce graduate and metalhead, he worked as a naturalist at a resort in Kollegal. That experience, along with a preliminary tour of the NCF’s elephant project in Valparai, led him to join the Hassan project in 2015. (He worked with the Hassan project until September last year.) In the early days of the project, Vinod was the lone ranger in the field station. He spent his days travelling to incident sites and talking to locals, who initially had misgivings about the city-slicker.

Gradually, he built trust and networks among the locals. “One day, a farmer at a scene of conflict was so irate that he called us useless and didn’t let us enter,” Vinod recalled. “But we insisted on investigating and stayed the night to see if the elephants would return. All this while, we heard him protesting, understandably. But the next morning, he invited us home and fed us rice that he’d grown on the land.”

The fault-lines of the region revealed themselves as Vinod spent a lot of time engaging with villagers and suggesting solutions. For Vinod, those years were also an education in elephant behaviour and ecology. In 2019, he co-authored an important paper about the elephant distribution across the Hassan and Kodagu landscape: his main finding was that elephants used acacia plantations or the limited forest refuge during the day, and moved to coffee estates and other agricultural land at night. [4] “We found that the majority of incidents occurred in the early hours of dawn, and some occurred at dusk,” Vinod said, “So we informed people and educated them about safety during the hours when elephant movement was the highest.”

“You have to stop looking at only saving human lives or the lives of the elephants, and start looking at the livelihoods of the people affected by conflict.”

The Elephant Information Network, a collaborative effort with local communities and the forest department, began in Hassan in 2017. The idea behind the initiative was simple: villagers would receive an SMS alert with detailed information about an elephant’s whereabouts, or they would receive a direct call from Vinod. “We then requested villagers to be mindful of the elephants during these hours and give them space to move around in the plantations and forest patches,” he said. Initially, some locals criticised the system, saying that it did nothing to manage post-conflict losses. But, in a few years, Vinod told me, the subscribers to the Early Warning Systems increased from 300 to 4000. Today, over 7000 people have subscribed to the alerts.

Since a majority of the conflict situations occurred on the main road, the team installed digital display boards at major junctions connecting the main towns of Hassan. The team also put in place alert beacons that were manually operated by community members when they were alerted to elephant presence by Vinod’s team. Today, over 15 display boards and 20 alert beacons are in operation in the district.

Vinod’s renown in the region has a lot to do with the way he interacted with the community. His team conducted monthly status meetings, patrolled high-risk areas during harvest seasons and even guarded crops at night when forest department personnel were stretched thin. They also held regular workshops in schools, and sessions for the gram panchayat.

With the forest department, Vinod also participated in division-level meetings. One of his goals there was to convince forest officials to be more judicious with capture-based management, and to make the point that it was important to deal with conflict by accepting that it couldn’t be done away with completely. The forest department remains an ally to the NCF. They share daily locations, assist with the installation of lights and boards, and collaborate on workshops.

“You have to stop looking at only saving human lives or the lives of the elephants, and start looking at the livelihoods of the people affected by conflict,” Vinod told me recently, “None of us can compute what a farmer loses when a year’s crop is destroyed. Most of the smaller farmers take loans for a year’s harvest, or for household expenses, and repaying them becomes almost impossible.”

n my last evening in Hassan, an RRT member called me to say that a herd of seven had been seen near the main road of an estate close to Rohit’s house in Ballupet. They were led by a bull we knew as Captain. When I reached the estate, I saw the herd feeding silently in a corner downhill. They had retreated somewhat because of vehicular movement on the main road.

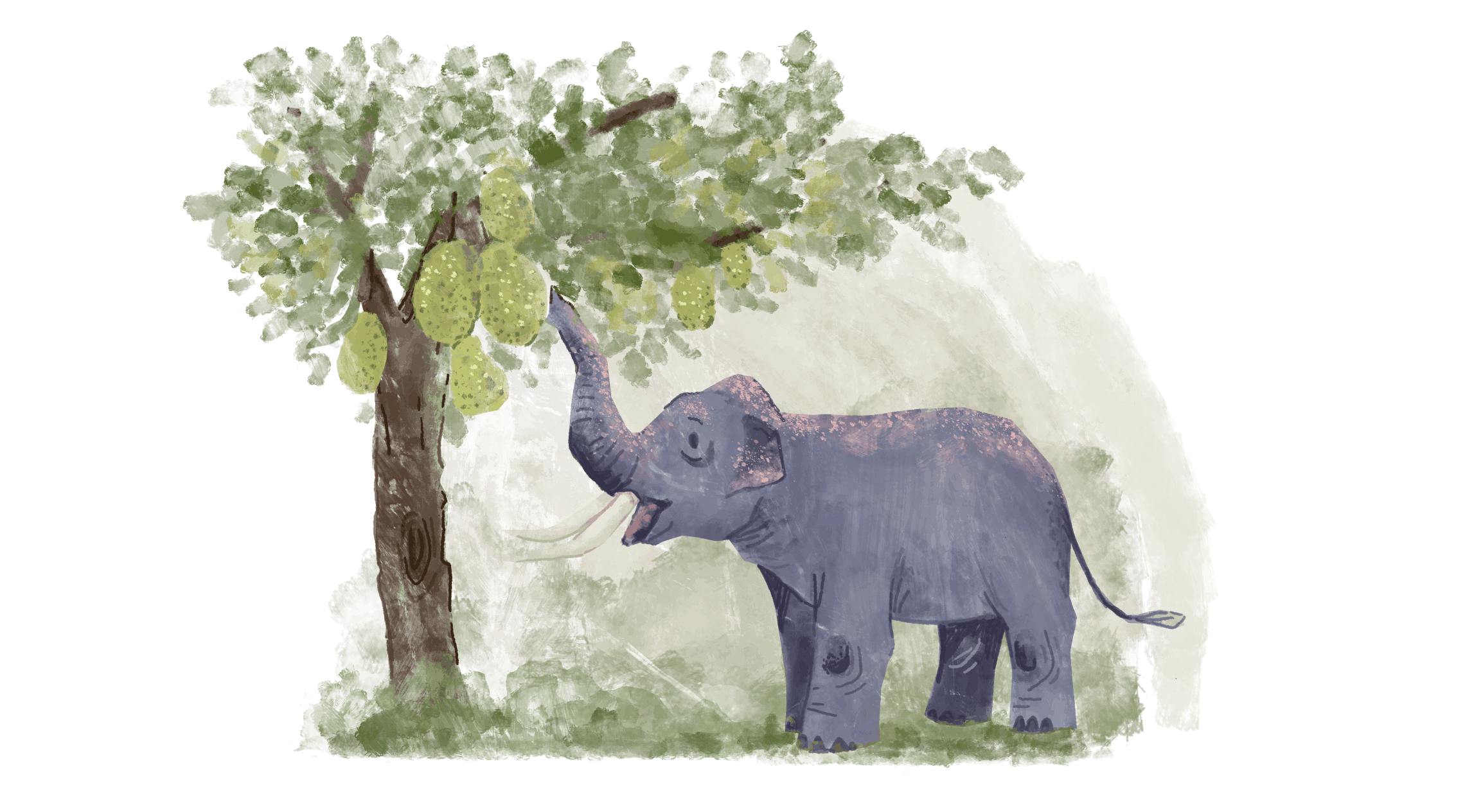

Through my binoculars, I saw Captain reach out for the remnants of the season’s jackfruit on a massive tree. The workers of the estate that had gathered around were mostly women. They asked that I pass around the binoculars. It hadn’t even been 30 minutes since they’d received the warning about the elephants on the estate, and scrambled to a safer spot. Now, they peered through the lens and giggled at the antics of Captain, as he delicately reached upwards for the last morsels. For those few minutes, they were not fearful villagers but enraptured spectators of a quiet moment in the lives of their neighbours.

Abhilash Pavuluri has donned several hats since finishing college in 2017. He currently works as a copywriter and independent journalist, but is itching to go back to studying human-animal interaction in India.