One winter morning in Shillong, a weary prosecutor tried to convince an irate judge to extend the custody of three queer refugees. The Border Security Force had arrested them for illegally crossing over into Meghalaya from Bangladesh in June 2020. They had been in jail for nearly six months at the time of the hearing. Bail petitions had been filed and denied while the case meandered through the lower courts before reaching the Sessions Judge.

It had been a long bleak pandemic in the trial courts. Everyone was exhausted and no one knew what to make of the case.

Everyone agreed that the three men had been found at Dawki, a trading town in southern Meghalaya. No one was claiming they were Indian. They held valid visas for India and had flown here from the United Kingdom—where they lived—before being stranded by the lockdown. They had slipped across the border to meet their families, the prosecution alleged, and had been arrested on their return.

The charge was that they had violated the terms of their visa, which allowed only a single entry into India. (Their travel documents, the prosecution admitted, had been “recovered but not seized” during the ensuing investigation, and then promptly lost.)

This meant that while everyone agreed it would have been illegal for Bangladeshis to enter Meghalaya without the appropriate documents, no one could prove that they had, in fact, done so. On what basis then, the exasperated judge wanted to know, was he to hold these men captive? There simply was no evidence to prove anything the prosecution was claiming.

To further complicate matters, returning the refugees to Bangladesh would make them vulnerable to persecution as sexual minorities. They had thus approached the court to release them from custody so that they could go home to London. As one observer said in court that morning: why do you need the Foreigners Act if the foreigners offer to deport themselves?

Burden of Proof

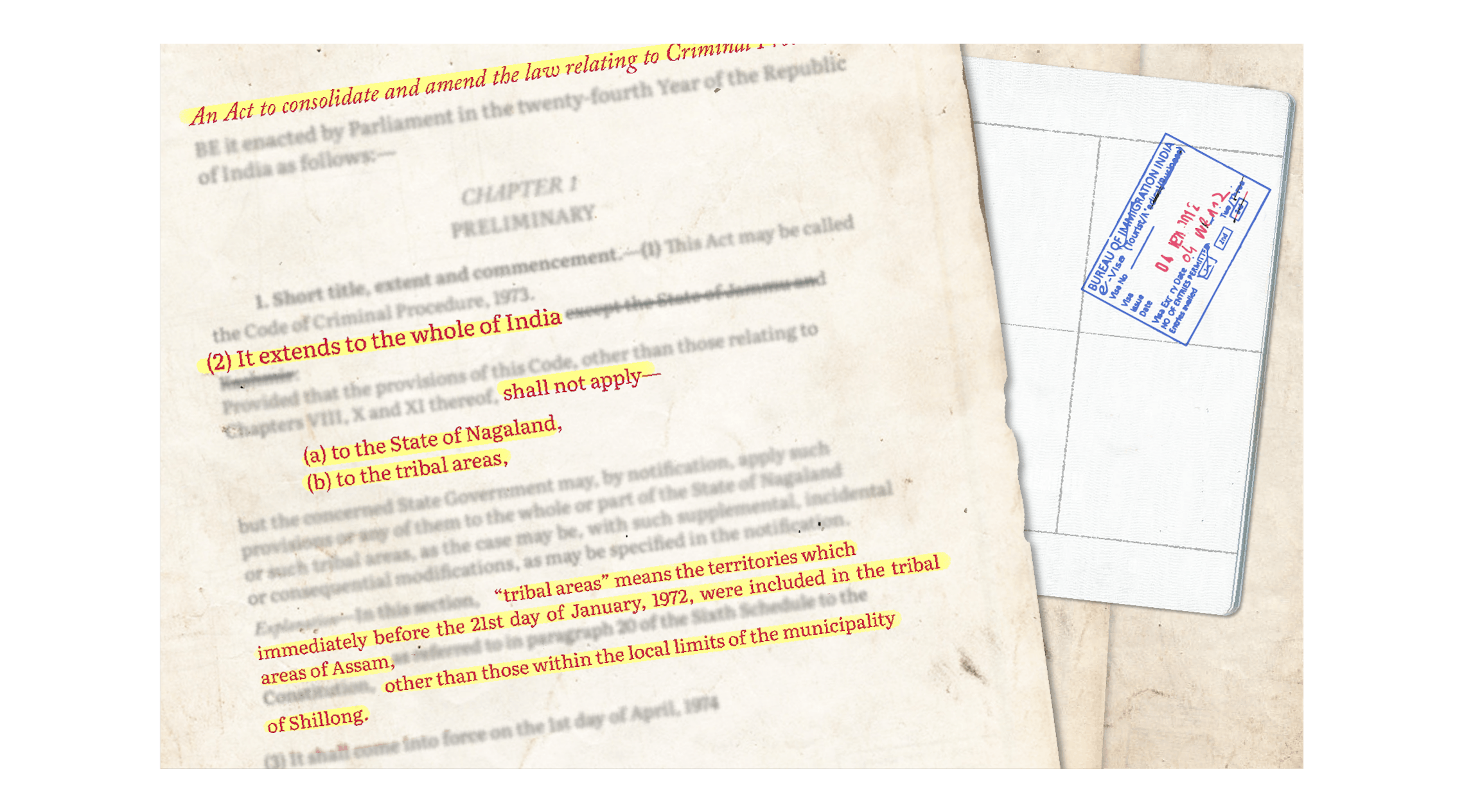

ndia’s first Foreigners Act was enacted in 1940, the culmination of the colonial state’s attempts to regulate migration within the empire and define the borders of British India. It was replaced by fresh legislation in 1946, which was amended in 1957 to define a foreigner as someone who is not a citizen of India.

The original legislations were about the determination of nationality rather than citizenship, two terms that imply very different things. Citizenship is a status that accrues to individuals within a polity that determines their responsibilities and liberties. Nationality, meanwhile, is an attribute of communities that can be identified either culturally or linguistically.

A colony like British India thus had a nationality law that did not address citizenship at all: the original Foreigners Act was intended to monitor the movement of people within the empire rather than to grant or deny anyone political privileges.

In independent India, the conflation between these categories has proved extremely contentious. It is one reason, for instance, that the National Register of Citizens exercise, first conducted in Assam in 1951, has been so controversial. There was no codified definition of an Indian citizen at the time—the Citizenship Act was only enacted in 1955—and the determination of nationality was precisely what was at stake. Were India and Pakistan one nation split between two states? Or were they separate nations, despite sharing language and culture across their various borders? The law cannot clarify what politics refuses to resolve.

The Foreigners Act further provides the legislative basis for Foreigners Tribunals, which have wreaked havoc in Assam in recent years. It puts the onus on alleged foreigners to prove that they are, in fact, Indian nationals (and, thus, by extension, Indian citizens). How this can be proved, with what documents, and with what certainty, is a matter on which the Indian judiciary is chronically incapable of making up its mind.

Such a reversal of the burden of proof is a routine feature of criminal law in contemporary India. But nationality was irrelevant to the case in Meghalaya, for the three refugees had never claimed to be Indian in the first place. The judge’s conundrum was more basic: could he simply take the BSF’s word that they had been caught crossing the border? Who was to say they weren’t simply taking a vacation in Dawki, a popular tourist town?

Could the state be given the benefit of doubt on the grounds that the Foreigners Act provides for the reversed burden of proof on one specific question, the determination of nationality? The prosecutor later told me that most judges would have accepted such a generalisation: it was to this judge’s credit that he held true to the foundational legal maxim that people are presumed innocent until proven guilty.

“Luckily for them,” the prosecutor observed wryly, “they were found in Dawki, not Karimganj.” He meant that if they had been discovered at the Assam border, they might well have been hauled before a Foreigners Tribunal, which would likely have interned them indefinitely in a detention camp.

“Luckily for them, they were found in Dawki, not Karimganj.”

The refugees were also lucky in other ways. They were lucky to have been granted asylum by the UK. They were lucky that the order dismissing their case provided extensive legal reasoning, making it harder to overturn on appeal. [1] Given that they were being held in Meghalaya, they were even lucky to be heard in this court at all. Meghalaya’s legal system, as we will see, is composed of three parallel hierarchies that operate in tandem, and two of them aren’t bound by the Criminal Procedure Code.

Most of all, the refugees were lucky that their unjust incarceration only lasted six months, because the judge examined the evidence comparatively early in the long road to a criminal trial. “Accused persons cannot be made to stand for trial merely on a narrative,” his scathing order observes, before pointing out that it is a waste of resources and an assault on personal liberty to detain people if there isn’t sufficient evidence to justify framing charges against them. [2]

A quick survey of bail jurisprudence in India makes it obvious that judges frequently do not have the luxury of such scrutiny. Terror suspects, for instance, find it challenging to approach the courts for relief until they have been detained for at least six months. Even penal statutes that deal with ordinary crime, such as smuggling or drug peddling, reverse the burden of proof in bail petitions. This creates a vast category of crimes for which people can be incarcerated on mere suspicion. Trials often take place only years later and more often result in acquittals than they do convictions.

Indians live today under a penal regime in which the process is the punishment. The consequences of this were laid out in a report submitted in 2003 by the Malimath Committee for Reform of the Criminal Justice System. The jurists who collaborated on the report insisted that the legal system is awash in “unmerited acquittals.” [3] This was their gloss on the dire reality that the Indian state routinely incarcerates innocent people. Their staggering solution to this undeniable problem was to do away with the presumption of innocence entirely.

The Malimath Committee’s report was unusually stark as such formulations go, perhaps because it was describing the reality of criminal justice in this country rather than seeking to reform it. They were merely proposing to normalise—and formalise— the way in which the system already functions: treating detainees like convicts and allowing the police to arrest and torture civilians with impunity in the guise of public interest and social order.

Some parts of India have more experience living under tyranny than others, just as some members of society endure more oppression than others. The fate, however, Indians hold in common. We inherited a legal edifice founded on racism and exclusion. Rather than dismantling it after achieving independence, we expanded it further, developing a complex web of exceptions to the course of mundane justice. Understanding that web is our best chance at unravelling it.

The most notorious of these exceptions, though neither the first nor the most common, is preventive detention legislation.

Reasonable Apprehension

ndependent India inherited some of its criminal legislation from the colonial state. Preventive detention, legal jargon for statutory provisions that allow the government to detain people for crimes they have not yet committed, is one such legacy.

It was extensively debated during the framing of what are now Articles 21 (right to life and personal liberty) and 22 (protection against arrest and detention) of the Constitution. The view that prevailed in the Constituent Assembly was that an elected Parliament was the natural custodian of citizens’ rights, and it would protect them more effectively than the elite judiciary. It would not curtail fundamental rights unless faced with a severe emergency. This admirably democratic sentiment did not fare well upon contact with the exigencies of rule. One month after the Constitution came into effect, Parliament passed the Preventive Detention Act 1950.

This sweeping legislation was challenged by the communist leader A.K. Gopalan in the Supreme Court. Gopalan argued that preventive detention violated the constitutional rights of citizens to equality and liberty. This argument was rejected by the Supreme Court the following year in a judgement that the jurist K.G. Kannabiran called “the first Indian-made foreign judgement.” [4] Gopalan’s own indictment was blunter. His trial, he said, would “expose constitutionalism as a bourgeois tool of oppression.” [5]

In the decades after that judgement, preventive detention laws and their abuse proliferated. They were challenged before the courts only to be upheld, culminating in the Supreme Court’s Emergency-era capitulation in the ADM Jabalpur judgement. (In that case, the Supreme Court had been asked to exercise the writ of habeas corpus to release prisoners detained without trial under the infamous Maintenance of Internal Security Act.)

Most states have passed a preventive detention law, and several Union laws now allow for it. Moreover, crimes such as conspiracy, sedition, and unlawful association are so vaguely interpreted, and have such low evidentiary burdens, that such detentions are functionally similar to those permitted by preventive detention legislation.

Preventive Detention laws work through intimidation, uncertainty, and secrecy. As the scholars Shrimoyee Ghosh and Haley Duschinski have observed, “the terrifying violence of indefinite detentions lies in the everyday uncertainty of not knowing what may happen next, since law and paperwork can be crafted as required to trap a detainee interminably.” While their research focuses on brutality of the preventive detention regime in Kashmir, this insight into the routine violence of such detentions equally captures the fates of those accused under the Unlawful Activities Prevention Act in the Bhima Koregaon and Delhi Riots cases.

The UAPA is not formally a preventive detention law; it just behaves like one in its disregard for the fundamental norms of procedural justice. India, like most liberal democracies, justifies such violations by appealing to the rule of law. It is necessary, the logic runs, to occasionally bypass some norms to preserve the rule of law, the very cornerstone of our polity.

The Rule of Law Myth

he rule of law is a powerful myth that sustains democracies and colonies alike. British lawyers found that it provided an ideal justification for their corporate empire. India, to them, was a vast and disorderly subcontinent, oppressed by tyrants who made up the rules as they went along. By contrast, their regime would provide the security and stability of codified law. J.F. Stephen, one of the architects of our criminal justice apparatus, wrote: [6]

“Our law is in fact the sum and substance of what we have to teach them. It is, so to speak, the gospel of the English, and it is a compulsory gospel which admits of no dissent and no disobedience.”

It was through the rule of law that the colonial state would civilise the mutinous millions of India. But there were several obstacles to overcome before a genuinely common law could be enforced across the territory. Personal law, for example, which regulated such things as marriage and succession, varied across communities.

Criminal law was considered more amenable to uniformity. It had been exhaustively codified by the late nineteenth century, resulting in a legal system that was seen as exemplary not merely for the colonies but even for the metropole. “To compare the Indian Penal Code with English criminal law,” Stephen proudly declared, “is like comparing cosmos with chaos.” [7]

It is certainly true that an uniform criminal law can be a useful technology for transforming a highly stratified society into a relatively egalitarian one. It is also true that in law as in life, substance inheres through process. The law doesn’t deliver justice simply by claiming it will, any more than a person becomes wise by asserting their own wisdom. A wise person is tested by time and by practice, by consistently doing and saying things that others recognise to be morally sound and practically useful. Similarly, the measure of justice for a modern legal system is whether it upholds, in practice, the values through which it justifies its potentially infinite capacity for coercion—values such as liberty, equity, certainty, and publicity.

A legal system that dispenses with the rules that govern a fair trial—which include things like the right to be heard and the presumption of innocence—defeats itself: without such rules, the law would simply cease to exist, on its own terms, as a valid social mechanism for regulating behaviour. This is doubly true for punitive laws. As Justice Khanna observed in his dissent in the ADM Jabalpur case, the “history of personal liberty is largely the history of insistence upon procedure.”

Savaging the Civilised

perceived lack of attention to process was, in fact, why “oriental despots” were treated so scornfully in Montesquieu’s influential eighteenth-century theory of liberal government. Montesquieu argued that despotic regimes didn’t distinguish between the executive function of enforcing the law and the judicial function of interpreting it. When J. F. Stephen imagined a “civilised despotism” for British India a century later, he believed that the strict adherence to rules of procedure in dispute settlement would ensure equity in the colony.

The law might be made by a select elite, according to rational and eternal principles that only a firm foreign hand, detached from the partisan squabbling of the subcontinent, could discern. But it would be interpreted and implemented equally and fairly, by an independent judiciary that was capable of speaking truth to power. This was the colonial rule of law.

There remained a limit to this evangelical discourse: the necessity of conquest. It was challenging, then as now, to reconcile the authoritarian reality of military occupation with liberal prescriptions for an accountable and responsive government. This, too, Stephen realised. The choice, he wrote, was not about “government by law and government without law.” The effort had to be “to unite by law all authority in one hand, to give by law wide individual discretion.” [8]

Even as he crafted the new criminal codes of procedure and evidence, Stephen helped draft two laws that would ensure certain places and people remained beyond their ambit: the Criminal Tribes Act 1870 and the Scheduled Districts Act 1874. Both laws codified existing practices for managing recalcitrant populations, especially in newly conquered provinces or frontier areas (which included most of what is now Rajasthan, Punjab, and Telangana).

A community designated a “criminal tribe” under the law could be displaced, surveilled, and harassed into working in plantations, mines, and factories for generations.

They did this by legally empowering colonial officials to ignore the new procedural codes that had been applauded as the beating heart of the civilising mission. The Scheduled Districts Act, for instance, sanctioned rules that combined executive and judicial functions. A community designated a “criminal tribe” under the law, meanwhile, could be displaced, surveilled, and harassed into working in plantations, mines, and factories for generations.

The echoes of these old and grim laws still resonate. The Scheduled Districts Act left a lasting imprint on the Indian Constitution. The Criminal Tribes Act evolved into a sprawling panoply of statutory provisions that criminalise marginalised populations en masse, including some that were eventually incorporated directly into the Criminal Procedure Code. The evil in these exceptional laws was less that they codified hypocrisy than that the people endorsing them justified severe repression with the pious certitudes of scientific racism.

Some people, Stephen explained in his speech introducing the Criminal Tribes legislation, were “destined by the usage of caste to commit crime” and had to be “exterminated like game.” [9] This irrevocable allegiance to crime was why, Stephen argued, such punitive legislation was necessary to control them, not the fact that such communities happened to threaten British paramountcy in the princely states (such as the Moghias in Gwalior) or disrupt colonial commerce (the Sanorias in Punjab).

If the Criminal Tribes Act deployed racist tropes about oriental fanatics, the Scheduled Districts Act excluded entire territories from the rule of law with equally racist fantasies about primitive savages. The Scheduled Districts Act was enacted once the centralised rule of the Crown replaced the fragmented regime of the East India Company.

Company rule had distinguished between “regulation” and “non-regulation” provinces. The latter included recently conquered territories such as Punjab and Assam, which local officials insisted were inhabited by savage and rebellious tribes who could not be expected to understand or respect the complex technicalities of civilised rule. Ruling such lands, they argued, required flexibility rather than uniformity.

A decade after the transfer of power, the Scheduled Districts Act was enacted to assuage such critics of Crown policy. It identified several districts across different provinces in which the ordinary laws of British India—including, and especially, the procedural codes—would not apply without the prior approval of the local executive. Such vast discretion in the hands of minor functionaries of the colonial government effectively made such officials that much-derided figure of liberal ridicule: oriental despots.

The Borderlands

he more proximate origin for this flowering of oriental despotism was, aptly enough, the longstanding tussle for power between the judiciary and the executive in British India. Both the Criminal Tribes Act and the Scheduled Districts Acts were legislative reactions to court cases.

In 1867, Punjab High Court struck down an executive circular that laid down surveillance and resettlement procedures for a community called the Sansis, who would eventually be designated a criminal tribe. The court held that such measures were unnecessary because the Indian Penal Code and Criminal Procedure Code “provided adequate measures for the restraint of professional criminals.” [10] The government’s response was to enact the Criminal Tribes Act so that the determination and administration of criminal tribes would now be a purely executive function.

In Assam, meanwhile, a local zamindar challenged the revenue boundary of the Garo Hills. He argued that his claim to land in the hills had been ignored when the border was legally established by Regulation X of 1822, which had also excluded the Garo Hills from the laws of Bengal Presidency. The Calcutta High Court held in favour of the zamindar in 1868. This ruling prompted the passage of the Garo Hills Act of 1869.

This law reinstated the boundary that had been struck down by the court, and further isolated the Garo Hills by depriving the criminal and civil courts of their jurisdiction over disputes in the district.

The law also provided for the possibility of expanded application, a power that was immediately exercised by the Lieutenant Governor of Bengal to include the neighbouring Khasi and Jaintia Hills District. When this decision was challenged, the Calcutta High Court struck down the enabling provision. The colonial government responded with even more stifling legislation: the Scheduled Districts Act.

Under the 1869 Garo Hills Act, criminal justice was governed exclusively by rules notified under the Act. The final authority was the Deputy Commissioner, whose decisions could be challenged politically by those sufficiently powerful to appeal to superior officers in the colonial bureaucracy. They could not be challenged legally: there was no right to appeal.

These rules had originally been drafted to operate in another part of what is now Meghalaya, the Jaintia Hills, following an uprising there a few years earlier. They were subsequently adopted under the Scheduled Districts Act. They remain the template for the administration of justice in most of Meghalaya today, though later amendments have restored the appellate jurisdiction of various high courts.

In the decades leading up to the Garo Hills Act, this part of Assam had given colonial dignitaries considerable anxiety. This was largely because of their inability to control corrupt local functionaries. The profligate excesses of one such petty tyrant, Henry Inglis, provoked three official enquiries in ten years.

Inglis had been appointed as a magistrate as a reward for tricking several chieftains into surrendering during the Anglo-Khasi wars. The English heir to the regional limestone mafia, he used his office to intimidate rival businessmen. When that failed, he directed his henchmen to sink his rivals’ boat and attack their men. When they protested to his superior officer—who happened to be Inglis’ father-in-law—he sued them for libel.

It was a conclusion that contradicted all the evidence on record, but better to be illogical than to admit that the only savages to be found in the hills of Assam were Europeans.

The most exhaustive of the enquiry reports into failures of justice in the region was written in 1853 by A. J. M. Mills, a judge from Calcutta. He argued that the problem, besides Inglis, was that it was unclear which laws governed what parts of Assam, who had authority and why, and where the borders of various districts even were.

Mills suggested that the concentration of authority and lack of administrative clarity had stirred rebellion in the area. A better remedy than the violent repression of such revolts, he said, would be “removing [the] anomalies” consequent upon the contradictory spectacle of a military occupation run like a civilian bureaucracy. It was time, Mills argued, to streamline and consolidate the rule of law in these areas, rather than retain the confusing medley of regulations then prevailing.

Others were more willing to vindicate the status quo. Five years after Mills’ report, the revenue officer W.J. Allen reported that Inglis continued his reign of terror, despite no longer holding any official postings, and that his prolonged influence had placed the administration “in a false position.” The unredeemable Inglis had made it impossible for other colonial officials to project an image of impartial justice, however “unimpeachable” their own behaviour had been.

Besides, it was easier to blame the victims for the despotism they suffered, and to argue that “these wild mountaineers have yet to learn the ready obedience which more civilised races cheerfully yield to purely civil authority.” It was a conclusion that contradicted all the evidence on record, but better to be illogical than to admit that the only savages to be found in the hills of Assam were Europeans.

This oscillating rhetoric of paternalism and repression characterised official discourse until the controversies provoked by the Garo Hills Act forced the colonial state to clarify the nature and structure of governance in the hill districts of Assam. Was it an established colony or a military frontier?

It was more expedient, ultimately, to retain the paradoxical ambiguity that facilitated the unscrupulous careers of men like Henry Inglis. It was the capital accumulated by ruthless planters, slavers, and mining barons, after all, that reconciled metropolitan shareholders to the frightful expense and bother of empire. Thus did the inhabitants of Shillong, by then the capital of British India’s richest province, definitively become primitive hill tribals.

Legacies of Exclusion

s more sophisticated laws began to expand executive discretion within the rule of law, the geographical scope of the Scheduled Districts was steadily whittled down. By the time it was repealed in 1937, the districts notified under the legislation had been officially “excluded.” There was also a great deal of official chatter about separating them from British India, in much the same way that British Burma was converted into an independent colony.

A decade later, the Constituent Assembly decided to retain the special status of the hill districts because of their alleged backwardness. The Sixth Schedule of the Indian Constitution, drafted specifically in relation to the hill districts of Assam, continues to give sweeping powers to the state Governor. Procedural codes, meanwhile, still do not fully apply to disputes in the “tribal areas” specified by the Sixth Schedule.

The legal geography this creates is bewildering. Depending on who commits which crime and where, they might be tried in any one of three courts. The first is the court run by the local Autonomous District Council, an elected institution created by the Sixth Schedule to protect tribal interests.

In Meghalaya, there are three such district councils, one for each of the primary tribes. The Khasi Hills ADC, or KHADC, has jurisdiction over Shillong. It is empowered to try criminal cases between Khasi people assuming that the crimes are charged exclusively under the Indian Penal Code, rather than under one of the many special statutes that have criminal provisions (such as the UAPA).

The second criterion is that the crimes being prosecuted by an ADC court must occur outside Shillong municipality, the borders of which remain highly contested. Crimes that occur within Shillong municipality are tried before the ordinary criminal courts, while those that implicate non-tribals (or, say, a Garo person on KHADC turf) are tried by the deputy commissioner of the concerned district or executive magistrates who report to him.

Non-IPC crimes are also tried by executive magistrates, who are often simultaneously judges and bureaucrats. The case of the three refugees, for instance, was technically being tried before the Additional Deputy Commissioner (Judicial), an executive posting, rather than the Sessions Judge of Shillong, the most senior trial judge in the district.

As often happens in such situations, the same person has been appointed to both posts. The judge in the Dawki case chose to follow the Criminal Procedure Code despite not being required to do so. This, while laudable, also makes his dismissal order in the case vulnerable. This slippage between the executive and the judiciary is why forum shopping is an established part of the life of criminal litigation in Meghalaya. If the purpose of this giant baffling mess was to make criminal justice more accessible to people, suffice it to say, it has roundly failed.

The only people in this institutional setup formally bound to follow criminal procedure are the magistrates and judges of the ordinary courts. Everyone else is only bound by “the spirit of the law” and a set of rules drafted to quell the Jaintia uprising in the middle of the nineteenth century.

The Spirit of the Law

he Supreme Court was first called to define the “spirit” of criminal law in 1966. The case was about the murder of “seven hostile Nagas” by the central police. The cops had been charged with murder and arson and were about to be tried by the Additional Deputy Commissioner when it was argued that the matter ought to be brought before a trial judge, rather than an executive one. The repeal of the Scheduled Districts Act, it was argued, naturally meant that the rules notified under it had also expired. How could a trial be conducted without any guidance besides nebulous imperatives such as “the spirit of the law”?

The Supreme Court did not agree. “Written law is nothing more than a control of discretion,” the judgement helpfully observes. The court upheld the old rules, reasoning that “the more there is of law, the less there is of discretion. In this area, it is considered necessary that discretion should have greater play than technical rules.” The judgement then goes on to argue that “the removal of technicalities leads to the advancement of justice in these backward tracts.” [12]

Even more astonishing was the court’s observation that “we must not forget that the Scheduled Districts Act was passed because the backward tracts were never brought under general Acts and regulations.” [13] That the court could assert this a few paragraphs after citing a case in which the Calcutta High Court angrily protested the removal of such tracts from the colonial rule of law a century earlier demonstrates the historical erasure at work. The court’s memory, at once fallible and expedient, reveals the priorities of the postcolonial state it served.

Once the assumptions and consequences baked into a once-controversial law disseminate so widely that they become common sense, it is redundant to retain the law on the books.

The logic of primitivism animating the Scheduled Districts Act has had a much longer life than the law itself. Legal voids don’t imply an absence of politics but rather an abundance of it. Constructing the excluded periphery, legally and logically, is the very essence of politics.

Law and history both sediment rather than repeat. Legal history is full of examples of laws that become obsolete without becoming irrelevant. Once the assumptions and consequences baked into a once-controversial law disseminate so widely that they become common sense, it is redundant to retain the law on the books. This is why we now have a diffuse and overlapping network of preventive detention provisions rather than a singular legislation that might attract focused critique.

We no longer have criminal tribes or excluded districts. We have, instead, “illegal migrants” and “disturbed areas.” These are new legal fictions that build on the legacy of exclusion and dispossession codified by those older categories. For every refugee rescued by a conscientious judge, thousands of Indian citizens suffer the violent fate of being deemed outsiders through no fault of their own besides the circumstances into which they are born.

Even today, one of the only parts of the criminal code that apply in formerly scheduled areas are the sections that deal with habitual offenders. This is a category we inherit from the dispossession of the communities once notified as criminal tribes. Every act of inheritance is also, however, an act of interpretation. We can continue to deny the lessons of the invented margins, or we can learn to live here.

Nandini Ramachandran, a lapsed lawyer, is a doctoral candidate in anthropology at the Graduate Center of the City University of New York. Most of this essay was written while she was conducting fieldwork in Shillong for her dissertation, a constitutional ethnography focused on the Sixth Schedule. She has also been a book critic for several years, and can be found online as @chaosbogey.