On a summer day in July 1972, the skies over Kabul were experiencing unusual turbulence, and the Indian President V.V. Giri’s aircraft, a Russian TU-124 called Rajdoot, trembled furiously in the raging winds. Giri was preparing to land in Afghanistan, but made a nervy entrance. The receiving party, which included King Zahir Shah and the Indian ambassador, watched the aircraft struggle to come to a halt. The plane veered off the runway and disappeared into a giant cloud of dust. They allowed themselves to imagine, for a moment, that the worst had happened.

This dramatic start to the visit was forgotten once diplomatic pleasantries commenced in stunning surroundings. President Giri proceeded to meet the acting Mayor of Kabul in the picturesque hill town of Paghman. “Your visit to Kabul manifests the desire for the consolidation of the friendly relations existing between our two ancient countries and peoples from this part of Asia,” the Mayor declared at a luncheon. He thanked the President effusively for the Children’s Hospital, which had been constructed in Kabul with Indian assistance. [1]

The President responded to this warmth with an announcement of his own. “I have great pleasure in announcing on this occasion,” he told the gathering, “a token gift of a baby elephant for the Kabul Zoo, and a few chandeliers and a water pump to be used in the Babur gardens and mausoleum. I fondly hope that these will add to the enjoyment of the citizens of the beautiful city of Kabul, and of its visitors.” [2]

It was the latest expression of the centuries-old cultural and historical ties between the two nations. Babur, founder of the Mughal dynasty, requested to be buried in one of his gardens in the Afghan capital. Songs from Hindi films played on the radios in Kabul’s shops. Among the most famous works of popular literature in the region was Rabindranath Tagore’s poignant short story ‘The Kabuliwallah,’ about a Pathan trader in Calcutta. The diplomatic relationship was built on a bedrock of shared culture, and the gift of Hathi was an act in which history, regional bonhomie, pop culture and diplomacy merrily coalesced.

r. Gunther Nogge was alarmed when he heard that an Indian elephant would soon be on its way to Afghanistan. Nogge, a zoology lecturer at Kabul University, was actively involved in the expansion of the city’s zoo, established only a few years earlier under the strategic counsel of his predecessor, Dr. Ernst Kullman. [3] When the zoo opened its doors to the public in August 1967, the prospects of keeping an elephant had seemed dim. The Kabul Times, a Western-friendly newspaper in those days, reported that expenditure for the zoo had totalled 900,000 Afghanis the previous year [4] —any plans to keep an elephant would have to be deferred.

A modest entry fee drew large numbers to the zoo. [5] In 1972, more than 150,000 visitors flocked to its lush grounds, a 20 percent increase over the previous year. By the summer of 1973, it was ready to welcome Hathi, a three-year-old female elephant from India. Just as Beijing Zoo officials had to construct their first elephant shed for the baby elephant Asha, presented by India to China in 1953, so too did Kabul Zoo’s engineers have to build a new accommodation for their new Indian resident.

Hathi’s hut was designed in an ‘oriental style.’ It was evocative of the enclosures of older European zoos, Nogge told me in a phone interview. In Europe, this style had the effect of exoticising both the animals and their countries of origin. In Kabul, however, the arched doorways and geometric patterns reflected an aesthetic with which the city was already familiar. Its occupant, too, was no exotic stranger to Afghanistan. Royal courts in the country had long used elephants for public parades, festivals, and hunting ceremonies. [6] But the last time an elephant was seen on the streets of Kabul was in the 1930s. For the city’s younger residents, it “would be a novelty, a wondrous new experience,” the American historian Nancy Dupree gushed in her guidebook. [7]

n pre-colonial times, rulers gifted animals to other kingdoms to signal submission or alliance. In the postcolonial era, independent nation-states presented animals to assert their national distinctiveness on the international stage. [8] By the 1960s and 1970s, elephants had become India’s unofficial cultural emissaries. They fit perfectly into Jawaharlal Nehru’s public diplomacy strategy.

Indian elephants traversed the world on ships and aeroplanes, bearing messages of goodwill and friendship. Under Nehru’s leadership, baby elephants were gifted to Japan, Belgium, New Zealand, China, Turkey, Canada, and Germany, often in response to requests made by the children of these countries. “The reason for presenting elephants,” reads a file from the Ministry of External Affairs, “is that it is an excellent advertisement for India, and it will produce a fund of goodwill for India in the beneficiary countries concerned, specially in the minds of the young generation.”

A grainy black-and-white portrait of Hathi appeared on page three along with details of her daily diet: 50kgs of straw and 14 buckets of water.

Perhaps the most famous of these elephants was Indira, named after Nehru’s own daughter and presented to the children of Japan. In his message to them, Nehru stated that they should not consider Indira a personal gift from him, but one from the children of India. “The elephant is a noble animal much loved in India and typical of India,” he told them. “It is wise, patient, strong yet gentle. I hope all of us will also develop these qualities.”

Occasionally, elephants were gifted to eminent individuals. Salvador Dalí famously requested a baby elephant as compensation for designing an ashtray for Air India. “I wish to keep him in my olive grove and watch the patterns of shadows the moonlight makes through the twigs on his back,” he waxed poetically to baffled officials at Air India. The wish was granted, and Darius lived in Dalí’s garden until he outgrew it and had to be transferred to Barcelona Zoo.

The gifts were often accompanied by public celebrations, processions, and broadcasts. When Nehru was in Tokyo in 1957, he attended Indira’s momentous ‘weighing-in’ ceremony in Ueno Zoo—she was now a healthy 3600kg. These exchanges also sparked the occasional diplomatic imbroglio. When Washington Zoo officials realised that a pair of elephants they were promised by Nehru, Ashok and Shanti, had doubled in size before they had been dispatched across the Atlantic, they began to worry. “Naturally, they have put on weight,” came the brusque response of T.N. Kaul, First Secretary at the Indian Embassy. “We cannot ignore natural development,” he said, leaving zoo officials to grapple with the implications for air transportation costs. (The elephants were eventually transported by ship.)

Hathi arrived by air on 18 June 1973. It was the middle of the Afghan summer, when the weather would have been just right for an elephant unaccustomed to the cold. In preparation for Kabul’s chilly winters, Nogge and his team ensured that Hathi’s hut had heating built into it.

Within two days of her arrival, Hathi was featured in The Kabul Times. A grainy black-and-white portrait appeared on page three along with details of her daily diet: 50kgs of straw and 14 buckets of water. It was speculated that bread and rice would be added as well.

Hathi was not the lone immigrant in Kabul Zoo. She joined an eclectic set from around the world: shimmering pheasants from China, Italy, India, and Africa; a bear from Turkey; fish and sea turtles from Germany. “A lion gifted by the Germans ran free and wild. American raccoons were raising a family and the Australian kangaroos were settling in well,” Dupree wrote effusively in her guidebook. It was a grand display of Afghanistan’s diplomatic friendships.

There was an impressive range of native-born animals, too. The zoo hosted a nocturnal flying squirrel from Paktia which slept with its tail wrapped around its head. There were porcupines from Paghman and leopards from Panjshir. Some animals were even loaned from the King’s private collection. [10]

“I was told people were very much excited about the elephant and there was a rush to see it at the zoo,” Nogge remembered. He himself had left the city a few months before Hathi arrived, in the summer of 1973. For a generation of Afghans, it was a novel encounter. “President Giri’s gift was very famous in Kabul,” AzizGul Saqib, the current director of Kabul Zoo, told me over the phone. As a young boy in the mid-1980s, he had been taken to Hathi’s enclosure by her keeper, who hailed from the same district as Saqib. Hathi and her keeper used to play a game of soccer, he remembered—she would playfully kick the ball the keeper threw at the enclosure wall.

In his book on foreign perceptions of India over the years, [11] Sam Miller wrote that Hathi also responded to light instructions from her Hindi-speaking mahout. In a rare colour photograph taken within a year or two of her arrival in Kabul, Hathi stands on a thick grassy patch, the top of her head and the arch of her back coated with a light sprinkling of grass. Her trunk is curled up towards her lip. Along the edges of the photograph, throngs of people can be seen pressed against the fence to catch a glimpse of her.

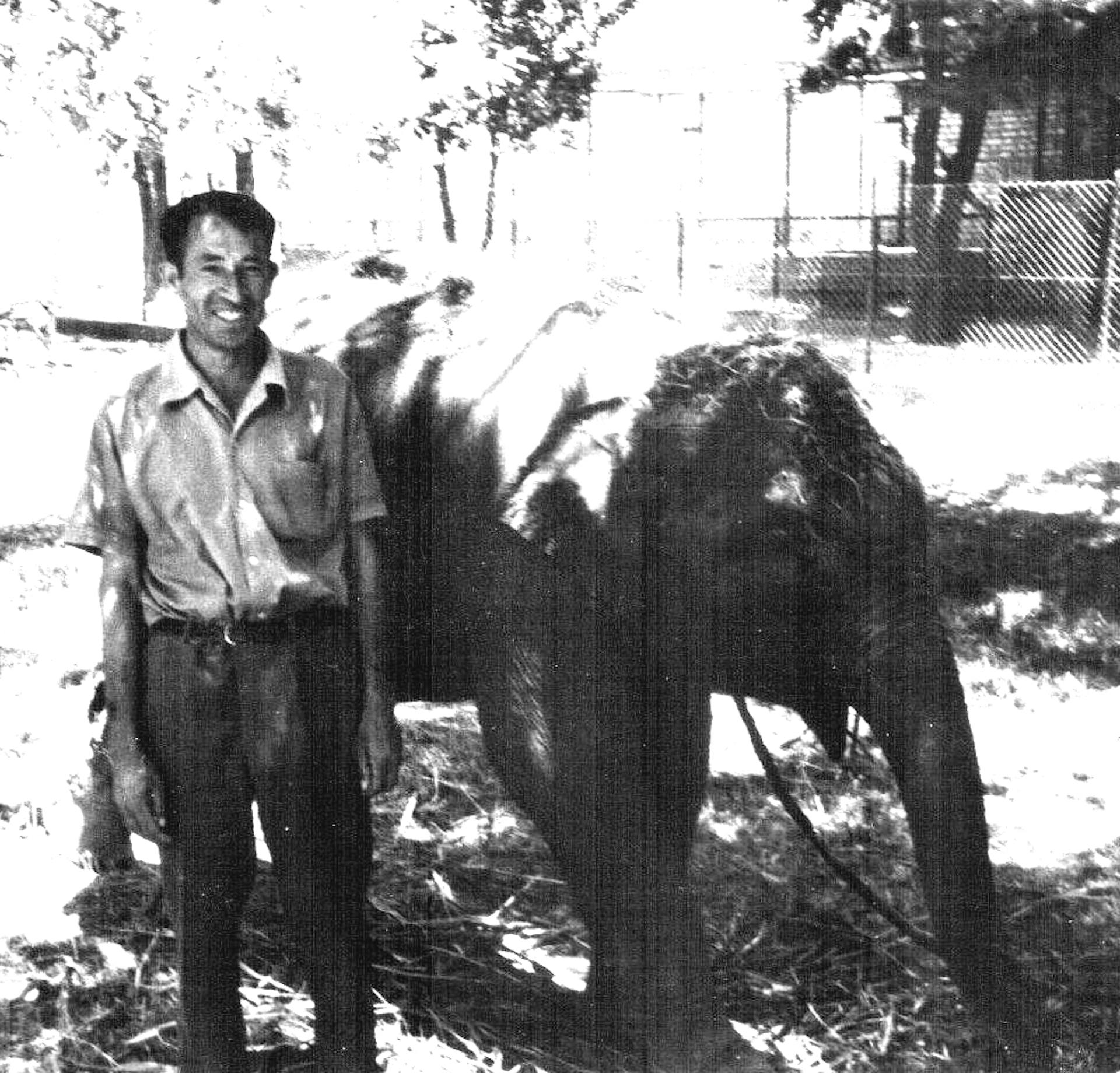

In a black-and-white photograph Nogge shared with me, his local friend Shehr Mohammad poses next to Hathi, looking cheerily into the camera.

From across the gulf of the years, mirth and melancholy intertwine to create an incongruous moment of happiness.

n 1979, Soviet troops marched into Afghanistan, setting into motion a decade-long war with devastating consequences. During the Soviet occupation, the Mujahideen, Afghan guerillas, controlled the countryside. Several cities, including Kabul, lay under the control of Soviet and Afghan forces. In attempting to destroy the safe havens of the Mujahideen, the Soviets depopulated and decimated entire villages, triggering a massive flight from the countryside. One million civilians were estimated to have been killed during the occupation.

“We were not supportive of the Soviet Union being militarily in Afghanistan,” Ambassador I.P. Khosla, India’s Ambassador to Afghanistan between 1989 and 1990, said in an interview with the Indian Foreign Affairs Journal in 2001. But India was a signatory to the India-Soviet Friendship Treaty, and its capacity to publicly condemn the occupation was limited.

Even with the withdrawal of Soviet troops in February 1989, skirmishes between the Mujahideen and the Soviet-backed regime continued. When Vijay K. Nambiar arrived in Kabul in October of the following year to take on his ambassadorial role, he noticed something out of place in the Indian Residence, located not far from the presidential palace. In the garden where some of Kabul’s finest rose bushes had once thrived, lay an eight-foot deep crater caused by a rocket attack from a few months earlier.

It was symbolic of upheaval in the city. On one unnerving occasion, Nambiar was inside the Indian Residence when a car parked at the Italian Chancery and Residence nearby was struck by a missile. Its bonnet hurtled through the window of the Indian Residence. Shrapnel scattered in all directions. [12] Missile attacks were routine by this time, and many were directly targeted at convoys carrying food into the city. “The effect on Kabul was devastating,” Sam Miller observed in a 1989 dispatch. [13] “Prices of foodstuffs and fuel spiralled and there was a lot of defeatist talk in the bazaars.” The Soviet-backed government was usually quick to react by launching targeted attacks using Scud missiles, left behind by the Soviets themselves. It also relied on the Soviets to airlift flour and fuel to Kabulis.

With its impending dissolution, the Soviet Union was eventually no longer in a position to supply Kabul with vital foreign aid. In 1991, India offered 50,000 tonnes of wheat to Afghanistan, as a grant, to help alleviate some of its troubles. [14] Due to logistical complications, though, the consignment never reached its destination, causing some embarrassment and strain on diplomatic relations. [15]

“I remember wondering ‘Why is its skin so dry? Does it need oil or something?’”

Outside of official channels, the bonds of Indo-Afghan friendship remained strong. Nambiar told me about his barber, who was extremely knowledgeable about Indian classical music. “One time, as I was getting a haircut, I could hear music coming from his transistor radio. He saw me shaking my head to the tune, and asked me, ‘Do you know whose music this is?’” A lively conversation about the nuances of Indian classical music ensued. “I mean, he taught me about the tabla traditions of North India,” Nambiar said with a laugh.

He recounted an instance when he invited his barber to attend a classical dance performance at the Indian mission along with senior dignitaries of the Afghan government. “He arrived well in time,” Nambiar remembered, “and without the slightest inhibition occupied the best seat in the front row next to the Vice President of the country.”

Later that year, in the tense winter of 1991, only a few months before civil war would engulf the capital, Amitabh Bachchan, Danny Denzongpa and Surendra Pal arrived in Afghanistan to film Khuda Gawah [16] in Mazar-i-Sharif in northern Afghanistan. They were escorted and lavishly hosted by a security detail led by Sayed Mansur Naderi, a militia man who served under President Mohammed Najibullah.

At a reception hosted at the Indian mission, the crew regaled the Ambassador with stories of the warmth and hospitality they had encountered—a conviviality that may have translated into the film’s generous, if stereotypical, portrayal of Afghanistan. Bachchan was even gifted a horse by Naderi, [17] a symbolic choice given the animal’s centrality to the film’s plot.

I asked Nambiar if he remembered the elephant at Kabul Zoo. “Yes, I think she was called Hathi,” he said. “I do recall that the zoo and the museum were under stress during this time. But the elephant didn’t figure in our discussions. We were more worried about the Children’s Hospital—it was one of our key projects.”

Such were the experiences of Hathi’s compatriots in the final years before the capital was taken over by the Mujahideen. To Kabulis facing an uncertain future, Hathi continued to offer whatever respite she could. On an autumn day shortly after the Soviets had withdrawn, the President’s daughters visited the zoo. Heela Najibullah, the eldest, was 11 then.

A rare colour photograph of young Hathi in her enclosure. Courtesy: Gunther Nogge

“There were not many kids around,” she told me. “There was not much noise. I always heard the birds when I walked around.” Hathi would have been a large adult elephant by then, about 20 years old. “What really did overwhelm me was the sheer size of it,” Heela said. “I remember wondering ‘Why is its skin so dry? Does it need oil or something?’”

n 24 April 1992, Mujahideen factions declared the formation of an Afghan interim government under the Peshawar Accord, ratified by many leaders in opposition to Najibullah’s government. “After 14 years, Afghan Guerillas easily take prize,” read a headline in The New York Times two days later. But Gulbuddin Hekmatyar of the Hezb-e Islami faction was discontented with his role in the new government. He refused to sign the agreement, and soon launched indiscriminate attacks on the capital.

“They had spotters in the city: Hezb-e Islami were able to infiltrate Kabul, it was easy. The aim was to terrorise the population,” one journalist told Human Rights Watch. Different factions of the Mujahideen, largely split along ethnic lines, began to turn on each other. The predominantly Tajik Shura-e-Nazar was locked in an intense battle against the Shia Hazara-dominated Hezb-e Wahdat. As their headquarters, the Shura-e-Nazar chose some of the city’s most familiar landmarks: the Baricot cinema, the Deh Mazang Square—and the Kabul Zoo, which was not far from where Wahdat and the Sunni Pashtun-dominated Ittihad were engaged in their own bloody battle.

The American photographer Steve McCurry first visited the zoo around this time. It was a rainy day and he didn’t take any pictures. The second time he visited, in April 1992, shortly after Najibullah stepped down, the zoo had become a frontline in the conflict.

“You had all these men with guns that had come in from other parts of the country, who had never ever been to Kabul, who had never even been to a zoo,” he told me in a phone interview. “I took one picture of them gathering up some straw from the floor.” It was not an attempt to feed the elephant, he explained—they were just poking the animal to see if it would move. “There was no sense of compassion,” McCurry said.

In McCurry’s photograph, Hathi’s back leg is chained. Unlike some of the other animals, who could at least walk around their enclosures, Hathi’s mobility was severely restricted. When McCurry went to see Hathi inside her hut, she was standing in her own waste.

Later that year, in December 1992, a new round of attacks erupted in Kabul. Plumes of black smoke were visible across the city as Wahdat and Shura-e-Nazar waged war, littering Kabul’s streets with anti-tank rockets and the spent cartridges of AK-47 rifles.

The National Museum was pillaged. Kabul University’s Faculty of Science, where the idea of a zoo had first germinated, was completely destroyed. “The whole country was becoming unglued,” McCurry recalled from his travels during those turbulent years. Although the precise number is difficult to ascertain, some reports suggest that around 20,000 people were killed between April 1992 and December 1994, with roughly half of those deaths said to have occurred in 1993 alone. Those who could afford it fled Kabul. The ‘Paris of Central Asia’ lay in rubble as the rest of the world looked away.

“I remember my father had once written in one of his letters, when he was in the UN compound, [18] that they (the Mujahideen) haven’t left anything, including the animals in the zoo,” Heela told me. “I remember being really struck by that. I have very vivid memories of being in the zoo.” The zoo, like so many other institutions during the civil war, was poorly attended and staffed. In between attacks, a zookeeper named Sher Agha Omar and his colleagues ferried in food for those animals that were still alive. On the days they were unable to make it, the zoo’s guard gave away his own food.

In April 1993, a rocket landed on the elephant hut. It was part of a particularly deadly attack, allegedly launched by Hekmatyar and which is believed to have destroyed about a third of the city. Hathi was seen and heard thundering across the compound in unimaginable distress. “She was so afraid. She didn’t know what was happening,” the zoo’s head keeper, Aga Akbar [19] told reporters. There was no medication to treat the injuries caused by the shrapnel; the shelling had destroyed the zoo’s veterinary clinics and its medical supplies. After ten days of suffering Hathi died, alone and helpless. She was 23 years old.

Kabul, Afghanistan, 1992. © Steve McCurry

When reporters visited the zoo after the end of the civil war, they found most of its enclosures empty and overgrown with weeds. The main administrative building was pockmarked with shrapnel and bullets. The entire first floor, where the museum and library had once been, was a pile of debris. AzizGul Saqib told me about a conversation he had with Abdul Latif Shanoori, the zookeeper who was in charge when the Taliban took over in 1996. “Why are the lions crying? They have food,” a vexed Taliban official had asked Shanoori. “It isn’t sufficient,” Shanoori replied.

The Taliban tried to close the zoo, arguing it was incompatible with Islam. They backed down only after Sher Agha Omar was able to show, with a little help from a Kabul University theology professor, that the Prophet himself had kept pets.

“Why are the lions crying? They have food,” a vexed Taliban official had asked Shanoori. “It isn’t sufficient,” Shanoori replied.

By 2001, the Taliban regime had fallen to invading NATO forces. “The total reconstruction needs have got to run into billions—how many billions, I cannot say,” declared Knut Ostby, then senior deputy resident representative for the United Nations in Afghanistan. The international community, including India, joined the reconstruction effort under the leadership of the country’s new President, Hamid Karzai, who had previously studied at Himachal Pradesh University under a scholarship provided by the Indian government.

India’s footprint in Afghanistan grew exponentially during this period. It began to invest in ambitious infrastructure projects—dams, highways, buildings, cricket stadiums, transmission lines—even as it continued to support social welfare projects in the fields of education and health, as it had always done.

“When Karzai came to power, the zoo started from zero,” Saqib told me. “There were no security walls, no doors, no electricity, no veterinary clinics, no food, and the aquarium was completely destroyed.” Zoo authorities worried that the zoo was too far down the pecking order of problems the government had to deal with.

Western zoos and zoo associations were able to mobilise nearly $150,000 in pledges, exceeding the wildest expectations of the zookeepers.“We had people emailing us saying that they didn’t give to the 9/11 fund, but were giving to this. I’m not saying that’s right, but that’s what some people are telling us,” Rod Hackney, spokesperson of the North Carolina Zoo, one of the zoos leading the response, told reporters at the time.

After the initial emergency response, which involved supplying water and heat to the enclosures and fixing the worst of the damage to the buildings, the zoo’s reconstruction began in earnest. It had become a global effort, with non-western nations like India and China among the leading contributors. China donated two bears, two lions, and a pig, much to the consternation of the North Carolina Zoo and the World Society for the Protection of Animals (WSPA), which both felt that the addition of new animals to a barely functioning zoo was unnecessary.

Through an arrangement funded by the Zoological Society of London and the North Carolina Zoo, Sally Walker of the Coimbatore-based Zoo Outreach Organisation facilitated an exposure and training programme for a three-member Afghan delegation in the winter of 2009. Over a period of ten days, Saqib and two other Afghan zoo officials—veterinarian Dr. Abdul Qadir Bahawi and educator Najibullah Nazary—toured seven zoos across South India to learn best practices in conservation and zoo management.

The spectre of elephants continued to loom large in the minds of some Kabulis. According to reports in 2013, Kabul’s dynamic mayor Mohammed Younas Nawandish declared: “I want elephants.” Saqib confirmed that there is, even today, strong interest in keeping an elephant at Kabul Zoo, although he acknowledged that an elephant keeper would need to be trained first.

It is unlikely, however, that an elephant will be crossing India’s borders as part of a diplomatic gesture any time soon. At the urging of animal rights groups, in 2005, the Manmohan Singh-led government imposed a ban on the practice of giving away animals as diplomatic gifts. Hathi had no successors.

ith revenues of about 33 million Afghanis (approximately ₹3 crore) a year from ticket sales and rent last year, Kabul Zoo is currently turning a profit. The aquarium and library have been rebuilt from scratch. Today, Saqib emphasises the zoo’s role as a centre for education and research, where Afghanistan’s youth can learn about the country’s native species and issues concerning the health of the planet. He also has plans to expand the zoo threefold, from its current seven hectares to 21. “Under the watch of the Sherdarwaza wall and the noon cannon,” [20] Dupree had written, referring to historic city landmarks, “the zoo can expand to the government owned farming land across the river.”

But Kabul’s troubles are far from over. Over the past few months, deadly ‘sticky bombs’ [21] have gone off in different parts of the city. [22] Taliban-backed insurgents and Afghan security forces continue to wrestle for influence, casting a long shadow of uncertainty over the country’s future. As Kabul’s public spaces surrender to security walls and concrete barricades, the relatively tranquil and open grounds of the zoo offer Kabulis a rare space for pause and leisure.

In a recent promotional video for the zoo, a montage of images appears against a buoyant background score: sparkling blue skies, lush patches of green, a preening peacock, a flowing fountain, children playing. The closing scene is of a little girl laughing so hard that she has to hold on to her sides. Her friend joins in, her face catching the sunlight. The ghosts of Kabul’s past hover imperceptibly around the frame.

“The request of the people of Kabul is for an elephant from India,” Saqib told me. “The elephant’s home is ready.”

Supriya Roychoudhury is a political geographer based in Goa.