Related Articles

Who is Dr. Kamla Chowdhry?

Dr. Kamla Chowdhry was an educator and a social psychologist. She was one of the founding members of IIM-Ahmedabad in 1961 and the defacto director of the institute until 1965.

18 Oct 22

When I first visited the esteemed Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, a sign greeted me in the exhibit along the subway pass connecting the old and the new campus. It featured large photographs of Vikram Sarabhai, the heroic scientist; Kasturbhai Lalbhai, the eminent industrialist; and Jivraj Mehta, former chief minister of Gujarat: THE MEN BEHIND IT ALL, it proclaimed. They were the “founding fathers” who played a vital role in establishing the institute 59 years ago. It was only later that I learnt that there was also a founding mother.

I first heard of Dr. Kamla Chowdhry in the corridors of Louis Kahn’s red-brick buildings, but not as any kind of pioneer. She was known as Vikram Sarabhai’s mistress. The description went beyond mere corridor gossip. It featured in a biography of Sarabhai written in 2007. [1] It was also used by Khushwant Singh in an Outlook piece in 2011. [2] Those readings were mostly about Sarabhai’s brilliance. Not enough has been said about Chowdhry’s.

Very few people today know about her incredible life, lived in places as varied as Lahore, Shantiniketan, Ann Arbor, Boston, Ahmedabad and Delhi. Fewer still know about the doctorate in social psychology she earned at Michigan University in 1949. She was the first faculty member of IIMA, and practically ran it in its early years. In 1962, the year the administrative office started functioning, its institutional partner Harvard Business School didn’t even admit women into its MBA programme. [3]

Thinkers such as Devaki Jain, Padma Desai and Isher Judge Ahluwalia––all economists––have published well-received memoirs in recent years. Chowdhry preceded them by well over a decade. Yet in social science academia, and even in the tight-knit networks of the Indian Institutes of Management, she remains something of an obscure figure. She is by no means alone on the sidelines of history: many Indian women scholars of her time have been subject to such forgetfulness, even though they were so few in number, and their circumstances so unique.

But sexism played a defining role in Chowdhry’s professional life, almost certainly barring her from becoming the first director of the institute she helped found. Now, new archival evidence is showing that she was more central to the IIMA project than has ever been publicly acknowledged. Today, on her birth centenary, it’s worth reflecting on her long and accomplished life, free of the shadows that others have cast on it for so long.

amla Chowdhry arrived in Ahmedabad in 1949 at the age of 28, having already undergone an eclectic education and a heart-wrenching tragedy. She was born in Lahore in 1920 to a Punjabi Khatri family where she was exposed to liberal ideals from an early age. Her father, Ganesh Das Kapur, was a leading surgeon in Lahore; her mother, Lilavati Khanna, came from a family of engineers involved in the building of the Sukkur barrage on the Indus river in Sindh. Kamla had gone to Rabindranath Tagore’s Shantiniketan, where she pursued music and learnt to play the sitar. After matriculating from Punjab University with a first-class degree in 1936, she earned a BA in mathematics and philosophy from Calcutta University in 1940: an unusual degree for women at the time.

She married a civil services officer, Khem Chowdhry, but the union proved short-lived. Khem, shockingly, was murdered by a person who had most likely been at the receiving end of his official strictures. He was killed as the couple slept: Kamla woke up to find him lying dead beside her. The murderer, a tribesman from the North West Frontier Provinces, confessed to his crime when he was apprehended in an unrelated case. The defence counsel for the murderer was a young Khushwant Singh, who told this story when he wrote Chowdhry’s obituary in 2006. [4]

In 1962, the year IIMA's administrative office started functioning, its institutional partner Harvard Business School didn’t even admit women into its MBA programme.

By the time the trial was concluded and the murderer received the death sentence, a traumatized Kamla had fallen into depression, not least because the Chowdhrys blamed her for Khem’s death. She did receive a condolence message from Tagore a few weeks before his own death: that letter counts among the last he sent in his life.

It would have been difficult, at that point, to imagine how her career would blossom. But inspired by Tagore and the ideals of Mohandas Gandhi, her life took a new turn. She dug her heels in and got an MA in Philosophy from Punjab University in 1943, where she stood first in her class. She went on to the United States to study further––by one account, a way to distance herself from the depression consuming her life. At Michigan University, she studied with Theodore Newcomb, who would come to be recognised as one of the most eminent psychologists of the twentieth century, and received an MA, and then a PhD, both in social psychology.

By 1949, she had become Dr Kamla Chowdhry, and was ready to come back to India. Her return took her to Ahmedabad, and to a job with Vikram Sarabhai.

Cambridge-educated nuclear physicist, future icon of India’s space programme, Sarabhai was still in his twenties in December 1947, when he set up the Ahmedabad Textile Industry Research Association in his family’s hometown. ATIRA was one of the first in a list of trailblazing institutions Sarabhai went on to build. It was a business-oriented one. Until this time, management in India was a fiefdom of family-run agencies. Sarabhai, scion of a family of textile industrialists, intended for ATIRA to apply scientific techniques in the research of industrial problems. [5]

The first four recruits to the organisation in 1949 were two chemists, a mathematical statistician, [6] and Chowdhry, who had first met Sarabhai five years earlier. Mrinalini, Sarabhai’s wife, and Kamla had been friends since their days in Shantiniketan. The meeting took place at Lahore railway station when the Sarabhais were passing through on their way to a vacation in Kashmir.

At ATIRA, Chowdhry headed up the Psychology division, which later came to be known as the Human Relations division. It allowed her to continue the theoretical work she had been doing in Michigan under Newcomb’s supervision. [7] Chowdhry was a scholar in a field that aimed to understand how humans behaved in groups, part of the wider subject area of organisational behaviour. Her work was to understand the socio-economic conditions, food habits and behaviour of workers in the textile mills of Ahmedabad. She spent hours at the mills, often the only woman at the site. Her division at ATIRA collaborated with the United Nations to study tensions among textile industry workers. [8]

Professor Chowdhry with Dilnavaz Sidhwa (left) and Harsha Rawal (right), the only two women who graduated with the first batch of the PGP (1964-66). The intake had three women and over 50 men. Credit: IIMA Archives

Because of Chowdhry and ATIRA’s work, the relationship among various stakeholders of the mill industry transformed over the next decade. Productivity and shop floor coordination improved. Workers and employees were able to gain a better understanding of wage and contract negotiations. Chowdhry was now organising conferences and collaborating with foreign researchers. When she went back to the US on a visit in the 1950s, she learnt about new research in her fledgling field.

For close to a decade, she had studied the textile industry and gained considerable administrative experience managing a division at ATIRA. She was indubitably an expert in her own right now.

But professional isolation had set in, and she was looking for opportunities outside Ahmedabad. It was because of this that Sarabhai actively began to look for ways to keep her engaged in the city—and that was what happened in 1962, when she moved over from ATIRA to run an institute that would one day come to be known as one of the world’s premier management schools: IIMA.

IMA was founded in December 1961 as a public-private partnership between the government of India, the state government of Gujarat, local industrialists and the Ford Foundation. Several people played an important role in its conception and founding. One of these was Douglas Ensminger, Ford Foundation representative in India in the 1950s and 1960s, who pushed for the creation of a business school outside the traditional Indian university system, itself a British legacy. Another was Vikram Sarabhai. He pushed for an IIM to be set up in Ahmedabad along with Kasturbhai Lalbhai, and Jivraj Mehta, the other “founding fathers.”

This is a widely accepted understanding of IIMA’s history. There are two books specifically devoted to the subject. What it leaves out is how closely Chowdhry was associated with the idea of the school, long before she was appointed its first faculty member.

The psychoanalyst Sudhir Kakar, Chowdhry’s nephew, dedicated a chapter of his 2011 memoir to his aunt. His account, based on her private correspondence with Vikram Sarabhai in the late 1950s, indicates that she had to be persuaded not to leave Ahmedabad. There were job offers from Delhi Cloth Mills and the Administrative Staff College of India in Hyderabad, among others; but Sarabhai put before her the question of leadership at an upcoming institute of management.

Archives in the United States, being studied for the first time, buttress this account. In February 1961, Sarabhai wrote to Dr. Fritz Roethlisberger, a professor of human relations at HBS [9] in order to refer Chowdhry for a researcher position, as well as to point out the imminent establishment of the first IIM. He hoped for “an active collaboration between the Harvard Business School and the Institute in Ahmedabad.” For her part, when Chowdhry applied for a research position with Roethlisberger, she lamented her “two to three years of professional isolation” and her “need to be a part of a professional group to share and learn new experiences.”

Roethlisberger accepted her to HBS in March 1961. The final acceptance noted her qualifications, and also the fact that she was associated with Sarabhai, who would “probably (be) closely involved in the Ford Foundation’s setting up of an Institute of Management in Ahmedabad.” For a few months afterwards, Chowdhry was a research associate under Roethlisberger. Like many institutes meant to encourage elite higher education in newly independent India, international collaboration was important for IIMA’s credentials. Chowdhry’s joining the HBS team was key for IIMA to secure a relationship with HBS over the University of California Los Angeles (UCLA), where initial talks were taking place.

Between 1962 and 1965, Dr. Kamla Chowdhry was designated ‘Coordinator of Programs.’ But as colleagues of hers later reminisced, she was the de-facto director of IIMA. Sarabhai, the Honorary Director, rarely attended to day-to-day matters, and Chowdhry’s range of responsibilities was staggering. She recruited the first faculty members; convened faculty meetings; liaised with HBS and the Ford Foundation; and travelled across India to market the Institute. She even selected furniture. “She was looking after the whole thing,” the late Dwijendra Tripathi, a business historian who worked at IIMA from 1964 to 1990, remembered. (He got the job, he said, because Chowdhry looked up the Fulbright scholars directory and found him there. It was consistent with how closely she paid attention to recruitment interviews.)

In spite of all this, and the full backing of Sarabhai and Prakash Tandon, chairman of IIMA’s board of governors, Dr. Kamla Chowdhry never became full-time Director of IIMA. As de facto director and senior-most faculty, she was the top contender for the post. But one peculiar circumstance, and the subsequent souring of the relationship between IIMA and HBS, put paid to that prospect.

“Only if it becomes absolutely necessary should we talk about blocking Dr. Chowdhry, but whatever we do, we must see to it that she does not become Director.”

The question of the directorship was by no means uncontroversial. It is, even today, one of only two folders in the IIMA catalogue of the HBS archives in Boston embargoed until 2045. [10] But the silence of this set of the archives is broken by others.

Over 1963 and 1964, a doctoral student from HBS, deputed to IIMA, wrote a series of letters to Harry Hansen, the director of the IIMA project in Boston. In this correspondence, the student accused Chowdhry of bypassing him, undercutting him and being too busy. He cast doubts on her teaching, research and administrative abilities. He even sent Hansen recommendations for the directorship position.

At one point, the young man proposed the creation of the post of Deputy Director. This should be an HBS appointment, he recommended, since “having an experienced Harvard man as a Deputy will make it easier for the Director to get acquainted with and carry out his job.”

More damaging were these unequivocal words: “Only if it becomes absolutely necessary should we talk about blocking Dr. Chowdhry, but whatever we do, we must see to it that she does not become Director, or for that matter Deputy-Director, or any other high administrative position.”

Whether his views influenced the decisions of Harry Hansen or others is difficult to pinpoint with certainty. But it is very likely that they added to any misgivings HBS faculty may have had about Chowdhry’s leadership abilities. Chowdhry was widely (and accurately) seen to be close to Sarabhai, and all communication to him tended to be routed through her. But Sarabhai himself was rarely around, and his absence, in effect, gave Chowdhry powers that were often misconstrued.

HBS was in no way obliged to vet IIMA’s choices for its leaders, yet it effectively vetoed Chowdhry out of contention. In 1972, the American team recorded the entire episode as a “misunderstanding” that led to the “ultimate detriment of the relationship” between HBS and IIMA. [11]

The fracas delayed the appointment of a director by three years. Prakash Tandon was explicit about the reason in his memoirs. He called it “HBS sexism.” [12] It was only in 1965 that a charismatic young faculty member from IIM Calcutta, with no doctoral degree, was selected. Ravi Matthai’s first year as director was threatened by a strike conducted by the Institute’s first-ever batch of students. He tided over it with the counsel of Dr. Kamla Chowdhry.

howdhry’s major and lasting contribution during her time at IIMA was in designing the institute’s first educational offering. The Programme for Management Development, aimed at executives, was launched in 1964 and later came to be known as the Three-Tiered Programme for Management Development or the 3TP: it’s still offered today.

When HBS began its Advanced Management Program (AMP) in 1945, it was directed at “men who are or soon will be in top management positions.” Feedback from AMP participants suggested that it was difficult for them to put their learnings to practice because employees had a hard time understanding these concepts.

Prakash Tandon and Chowdhry had both attended AMP sessions, a decade apart, [13] and they knew the 3TP experience had to be different. Here, Chowdhry’s expertise in human relations and group behaviour came to the fore. Learning from the American experience, she noted that the development should be company-wide and “undertaken in breadth and depth.” It was important for the 3TP programme to be “oriented towards the company rather than the individual.”

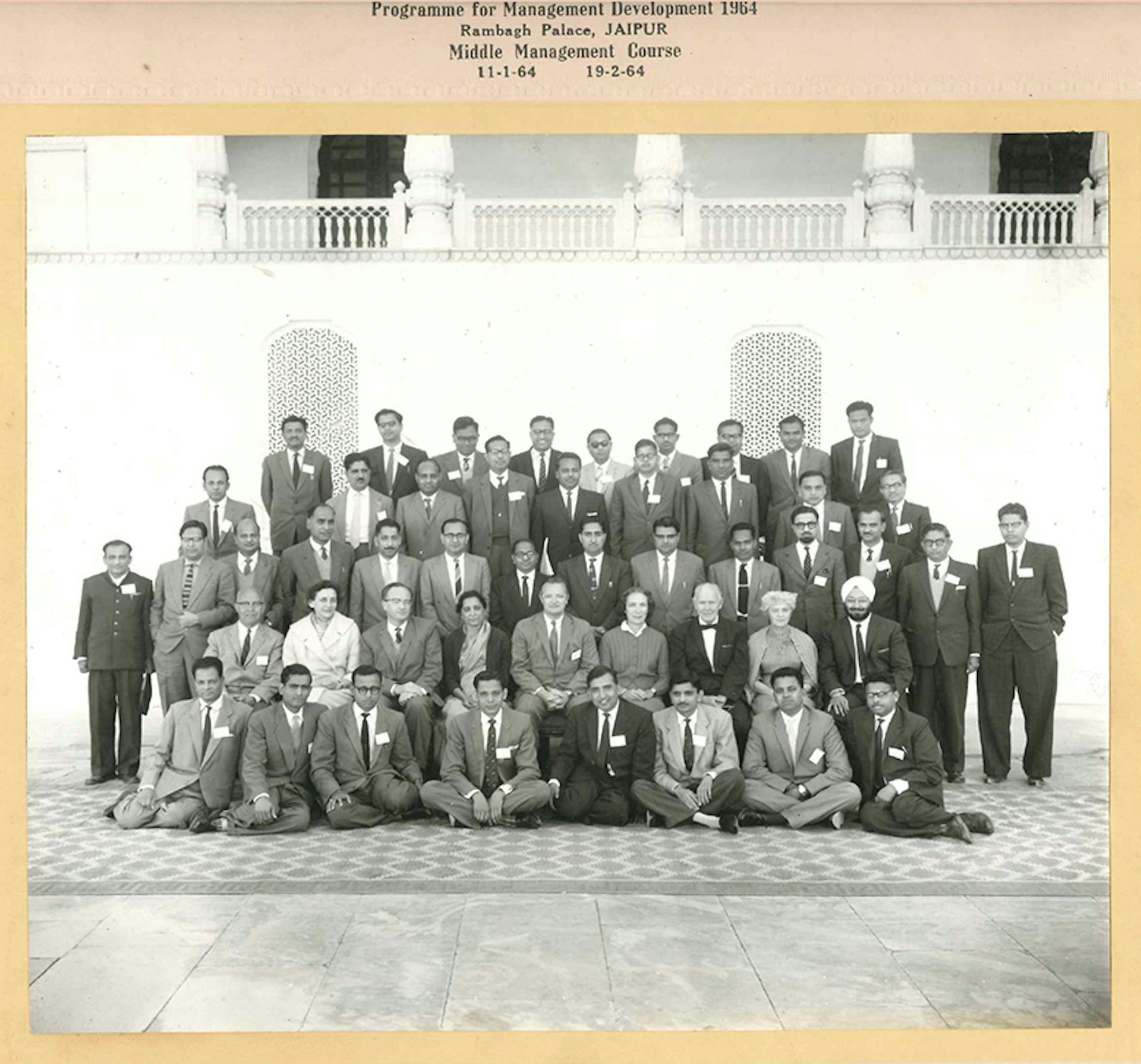

Companies were asked to send executives across the three tiers of the organizational hierarchy: middle management, senior management and top management. The Institute customised programmes for each level, spread out over five to ten weeks. The first edition in Jaipur in 1964 was a roaring success—it attracted 40 companies and 120 participants. At least two executives from that cohort went on to become icons in the Indian business landscape: HT Parekh of ICICI and then HDFC; and Dr. Verghese Kurien of Amul. It formed part of the groundwork needed for the launch of the full-time MBA programme.

Participants and organizers of IIMA’s first executive education programme, held in Jaipur in early 1964. Kamla Chowdhry is seen seated in the middle of the second row. Credit: IIMA Archives

After 1965, Chowdhry’s focus shifted from administration to teaching and research. We know that former students have fond memories of her classes. Her case studies included research on firms such as Unilever and Sarabhai Chemicals, and Chowdhry maintained strong links with industry as a consultant.

A range of Institute-related projects occupied her in these years: in the summer of 1966, she chaired a working committee to draft the constitution of the Institute’s alumni association. In October of that year, she became the first person to hold a chaired position in Indian management education. [14] In March-July 1968, she became among the first women to be appointed visiting faculty at Harvard Business School.

n 1971, Vikram Sarabhai died unexpectedly in a hotel room in Kerala. Chowdhry left IIMA the following year, and moved to Delhi. The capital became the site of further reinventions. In the 1970s, she worked with the India office of the Ford Foundation. In decades to follow, she moved away from management and took up environment and sanitation-related causes.

In the 1980s, she led the National Wastelands Development Board. She also served on several high-level international bodies, most notably the World Commission on Forestry and Sustainable Development and the United Nations Panel of Eminent Persons for the World Summit for Sustainable Development.

She did not lose touch with the Institute she had helped build. In 1976, she donated the bronze bust of Sarabhai for a library that is named after him. In 1988, she was conferred an honorary doctorate by IIMA after JRD Tata and Prakash Tandon had received them in 1982 and 1984 respectively.

When not attending some board meeting or the other, she could be seen swimming powerfully in the pool maintained by the Ford Foundation.

At every stage, Chowdhry had made it a point to argue for more women being admitted to IIMA’s flagship MBA programme and included in the faculty rolls. Years after the directorship imbroglio, in 1987, she wrote: “I remember there was an unconscious bias against the induction of women in the faculty—there were only two or three women faculty members. This was because of Harvard which was not known to be having any women faculty members. However, I had to fight strong battles with admissions to have more women in the PGP [MBA].”

Her crusade for gender parity in academia and industry continued outside the walls of the campus. In the June 2013 edition of the alumni newsletter, Savita Mahajan, who graduated from IIMA in 1981, recounted how a recruitment poster appeared on campus that stated that “women need not apply.” This advertisement was for positions in the prestigious Tata Administrative Service management trainee programme. Chowdhry took up the matter directly with JRD Tata, and the rule was overturned the following year.

It is true that Chowdhry’s intellectual and romantic relationship with Sarabhai shaped her life in important ways. But it has been grossly unfair to take stock of the staggering list of her professional achievements through this prism. Her story will remain incomplete if her rich and complex inner life is anchored to just one attachment.

For those who knew Chowdhry well, several traits stood out. Her mentorship abilities were as renowned as the flask of gin she never failed to carry on her trips. To women such as her niece, Nina Singh, she was a paradoxical figure who admired beautiful things like carpets and paintings, but spent too little time on her own appearance. In her later years, Chowdhry lived close to Delhi’s serene Lodhi Gardens. When not attending some board meeting or the other, she could be seen swimming powerfully in the pool maintained by the Ford Foundation.

After her death at the age of 85 in 2006, her well-wishers published a book of tributes. It captured some elements of her journey, mostly after the time she was at IIMA. Sunita Narain of the Centre for Science and Environment (CSE) would write that she “was first and foremost an institution-builder and an institution-keeper.” Today, Kamla lives on in Ahmedabad in certain ways. Finally, and fittingly, concrete steps have been taken to rewrite her into IIMA’s institutional history. [15] Dormitory 1, mainly for women, at the Institute has been renamed in her honour. The Self-Employed Women’s Association (SEWA), one of several organizations on which she left her mark, [16] runs a restaurant named Kamala Café, where her photograph occupies a prominent space.

Yet there may never be anything like an adequate memorialization of the woman who once wrote: “Most changes that have altered the course of history have begun by individuals who by their examples and actions did what many thought was impossible. Underlying each one was a moral conviction, a fearlessness, that refused to be subdued.”

Chinmay Tumbe is a faculty member at IIM Ahmedabad and author of India Moving: A History of Migration and The Age of Pandemics.