I’ve slept just five hours when the alarm goes off at seven. Some morning jazz, a cup of hot black coffee, a slight breeze at the window: the day has to start real slow because I won’t find peace in the cauldron of the commercial kitchen. I look forward to its music anyway: the beautiful sizzle of meat on the pan, sharp blades hitting the chopping board, the relentless beeps of the ovens, the creak of the billing machine. This, too, is a kind of jazz. Each artist plays their part, and seemingly disparate notes come together as one.

I’ve wanted to be a chef for most of my life. I wanted to strut into the kitchen in a spotless white coat with spoons in my left shoulder pocket. My dream restaurant would be called Sadaf’s. My food would take you down memory lane. Most importantly, I’d arrive to work on a motorbike. I’d travel the world, host TV shows, erect a cookbook empire. Naturally, brands would fall over themselves to sign me up.

There’s a lot that happens between the grime and glamour. People like me, we’re home cooks who want to take it to the next level, cooking show participants who want to “break into” the industry, line cooks with a passion for plating and storytelling. We look at the big fish, the Ranveers and the Sanjeevs, the Julias and the Nigellas, and that’s where we want to be. If you think there are roadblocks on the path, you’re right. I went from home cook to a chef in Delhi restaurants. I’m a striver, and this is how my story began.

The Show

ther children played cricket and learnt to ride a bike. I plonked myself on the kitchen slab and stared at boiling milk. My paternal family is one of those that talks of nothing but food when they meet. I was a little ball in my childhood because I thought being the fattest kid on earth was a point of pride. When I was tall enough to reach the kitchen counter, the first meal I made was sponge gourd and roti. (The tori ki sabzi was edible, but even canines would have had trouble tearing into the rotis.)

I grew up in a small town called Ramgarh in Jharkhand, and went to Ranchi to get a degree in advertising from St Xavier’s College. I followed that up with a master’s degree in animation from a private institute. In 2011, I moved to Delhi to look for a better job—a time of struggle, but not difficult, now that I look back on it. My brother took care of me until I landed my first full-time gig at an economics think tank. To shake off the pressures of the working week, I began to spend hours in the kitchen on weekends. It helped to have a bad memory for recipes. I was able to give free rein to my intuition and imagination.

It got to a point where I just had to give professional cookery a shot. In 2015, my friend and ex-colleague Manasi Bose, baker extraordinaire, started a pop-up café called Bread and Better with me. We went to people’s houses and rustled up European breakfast classics: fluffy pancakes, crispy hash browns, grilled meat, cakes. All this while the hosts hung out with us and other random diners; networking, discussing worldly issues, becoming friends.

The year after, another colleague pushed me to audition for MasterChef India. The first round was in Delhi during the month of Ramzan. I put together Malaysian satay chicken with spicy peanut butter sauce on an empty stomach. I had to impress three different sets of judges, so I went from room to room, offering a taste. I made it through to the next round.

They flew me to Mumbai for my final audition, where, at crunch time, I had to pass a version of the show’s ‘hero ingredient’ round. My assignment? The orange. So I made it the star of my îles flottantes or floating islands, made by perching meringue on a pool of crème anglaise. It’s one of those elegant French puddings that looks minimal but are bewilderingly hard to get right.

I made both my meringue and custard orange-flavoured, and I got it right, because the judges approved. I was going to be on TV, in a competitive cooking show that had taken the world by storm.

Being on MasterChef was a whole other trip: cook good, look good, get inspired. For four months, Hotel Karl Residency in Andheri was our haven and our fishbowl. The hotel’s staff and rival contestants became family. Every day, on set and off it, there were hits and misses. My big shake-up came the day I prepared a stunning dish of grilled chicken thighs and pan-tossed mushroom sauce. The plating was just beautiful, if I may say so myself. My legs were wobbling as I walked up to present it.

My dish made it to the top five that round. But—there’s no nice way to admit it—I also served a piece of raw chicken to one of the judges. Crushingly for me, the segment had to be reshot with a different contestant. I accused myself silently at that moment: you didn’t double-check what you plated up. I’m grateful no one outside the studio got to see my face when restaurant baron Zorawar Kalra pointed to a little piece of pink meat peeping out from his plate.

We did some fun things on that show. My team once won a challenge by putting together a tiramisu in which we substituted the traditional coffee with tea—my idea—and crafting a version that contained orange liqueur and jelly. (Don’t knock it until you’ve tried it.) Alas, I met my nemesis in the fine art of spherification in the molecular gastronomy round. The Catalan masters would have been disappointed. My dream crashed.

One of the things you don’t realise as an audience of these shows is that very few of us know what we’re going to do next. I still wanted to be a chef. But I had no degree, no blue-chip training. Appearing on a primetime show meant I now had admirers. But it didn’t wish away the doubts.

n the end, there was nothing to do but swallow my jealousy and sadness, wipe off the makeup and burn my hands in the tandoor. When I left the show, the charismatic chef Vikas Khanna said that he was looking forward to eating at my restaurant one day, which was the kick in the gut I needed.

So began my journey in the belly of Delhi’s restaurant kitchens. It was to feature at least one bust-up, some unlearning and a whole lot of trade secrets. My first gig was with a café in Connaught Place that I won’t name. I got to wear the chef's coat and swagger about a bit. The line cooks were chuffed to work for a chef who’d been on TV, but the head chef remained suitably unimpressed: a few big names were dropped in conversation, and I was reminded that he has been in professional cooking for more than 15 years.

Weekends, a time for relaxation for eaters, is combat time for cooks.

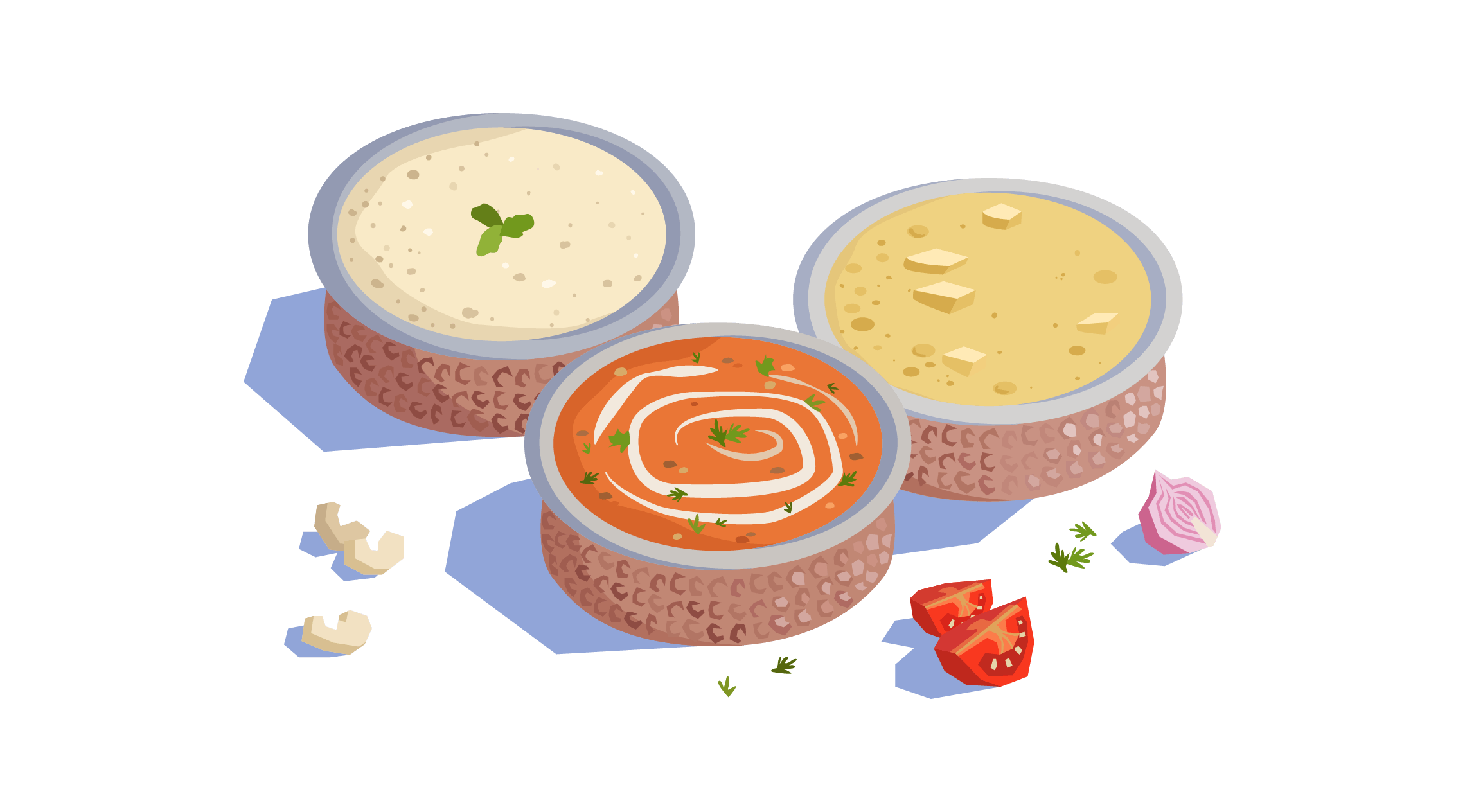

He told me restaurant cooking was very different from my home kitchen efforts, and he was right. It wasn’t long before I was introduced to the three “mother” gravies of the commercial cooking business: yellow, makhni and white. (You may think of them as Buttercup, Blossoms and Bubbles while the chef plays Professor Utonium.) The yellow and makhni gravies are prepared in varying ratios of onion and tomato; the white gravy is cashew and cream-based.

These royal bases—fundamental to Indian cooking—are prepared in industrial batches and frozen for weeks, alongside the reliable ginger-garlic paste, and the humble pea. Batches of vegetables and meat are pre-cooked and marinated daily. (I’ve also worked in smaller restaurants where half-cooked or marinated meat is stored for at least three to five days.) This is why your lavish Mughlai dish is tabled within 15 minutes of your ordering it.

Weekends, a time for relaxation for eaters, is combat time for cooks. On Saturdays and Sundays, my job is to keep the workflow smooth, the plates good-looking, and tempers at bay. Osama Jalali of the catering company The Mughal Plates, one of my favourite people in the business, once told me that after all these years, he still sleeps for only four-odd hours on the weekends.

(Speaking of Mughal plates, let me comment on the creation of biryani, now India’s favourite food. Very few commercial kitchens, at least in North India, cook it the way your mother would. The average restaurant biryani is what I call a ‘jhatka biryani’—jerked together in the snap of a finger. When an order comes in, we toss chicken qorma into pre-steamed or smoked rice and seal the pot. The dish is ready in 10 minutes but diners are made to wait for at least half an hour. Who’d enjoy a biryani that arrived any quicker?)

You, a sophisticated consumer of hit foreign shows about food and restaurants, probably won’t ask a chef if they get to eat all the good food they make, but it’s actually the most common question we get. At restaurants, most chefs never get to do that. The exception is the head chef, who takes on this task because they have to, not because they want to. They have to be the first critics, the ones who spot that the gravy today tastes exactly the same as it did yesterday, and the marinated meat that came out of the freezer hasn’t gone off.

Kitchen staff, especially line cooks, are a bit like masons. They don’t get to live in the houses they build. I once worked with a master chopper in the kitchen of a West Delhi restaurant. All I had to do was request the kind of cut I needed and I’d have it, perfect shape and all, in the blink of an eye. For almost two years, day in and day out, he chopped expertly and also rustled up the base gravies. Not once was he given the opportunity to try his hand on the cooking range.

Tempers and Tempering

hen I began my career, I had the noble ambition of recreating the casual chic of the bistros of Italy and France. I had to snap out of it when my first diners asked for pasta. I served them an al dente delight, delicately sauced, with a touch of cheese. But the customer wanted what I call Punjabi pasta—dunked in ragu and doused in mozzarella.

The diner is king. That’s a hard lesson for many chefs. More specifically, the diner is a college-going boy and his girlfriend who will leave after treating themselves to a few beers and food that sets their mouth on fire. They want their pasta to be full of tangy sauce. Give it to them. This doesn’t stop chefs from complaining in private, of course. “I am sorry, I’m not going to serve trash even if the diner is used to it,” a chef from Mumbai whom I cannot name, told me defiantly. “I am going to serve authentic food, and not the bastardised version.”

He makes pizza, perhaps among the two or three most bastardised foods in the world. “It’s full of substandard cheese and tastes like cardboard,” the angry chef said, of the version most Indians eat. “Pizzas are supposed to be flatter, with just enough cheese, sauce and toppings! You want to be able to enjoy the flavours!”

I have to say I see where he’s coming from. One restaurant I was working with in 2018 had pizza on the menu. I, too, served it flat and used high-quality mozzarella sourced from a vendor in Gujarat. The best I can say for its success is that it had its fans. But the number of times I had to take the order back and serve something else told the real story. It is a matter of taste, and I accept the verdict gratefully. Changing the way people eat needs time, money and energy. Almost no one has that sort of luxury as a chef.

A big part of running the show is managing tempers and egos, and not just the diner’s. I don’t like shouting or bossing people around, which is what most people think chefs do, having watched Gordon Ramsay blowing his top at aspirants on his TV show, or Catherine Zeta-Jones in No Reservations. The yelling and screaming is more common among chefs from generations before my own.

Of course, people have different reasons for kicking up a ruckus in the kitchen. When I was in Patna for a pop-up, I saw a junior chef get an earful because he’d used a tablespoon to taste the food. (The convention is to use dessert spoons for tastings.) My friend Ruchira Hoon, consultant chef and journalist, has to raise her voice a bit so that the overwhelmingly male staff doesn’t take her for granted.

You don’t attack someone with a bottle in my kitchen, and especially not on my team.

I’ll always remember an incident at a Central Delhi café where I once worked. I was enjoying my break one day when I got a call from one of the chefs: there had been a clash between the manager and the youngest chef on my team. It was not a regular argument: the manager had thrown a beer bottle at the chef. It missed the young chef’s head by inches, which saved his life, though not his employment. He was fired.

The next morning I discovered that the chef had taken objection to the manager helping himself to food that was meant for a guest. The veteran was offended by the young chef’s perfectly reasonable intervention. I lost it, too. You don’t attack someone with a bottle in my kitchen, and especially not on my team. For me, retaliation just meant putting in my papers. I cannot, to this day, tolerate fragile male egos in the kitchen.

#ChefLife

think this may be because I underwent so many trials myself. Professional cooking can be especially hard on home cooks. When I started out, I perceived disdain from the ranks of chefs from storied culinary families, and those with fancy degrees from top schools. There was nothing to do but accept that some people would reserve the word “chef” only for others like themselves.

This is how you can tell I’m an outsider: one of my biggest desires when I went into MasterChef India was to earn my very first chef’s coat, rather than have it stitched myself. The spanking white chef’s coat is the mark of your vocation and passion, and the symbol of your routine. It’s what you’re thinking of when you see the hashtag #ChefLife on Instagram.

I wear blue and black coats now, but that white one still feels like the peak of accomplishment. I remember how struck I was when I first met Chef Ashish Bhasin, director of culinary operations at Leela Ambience Gurugram Hotel and Residences. Of all the spotless coats I’ve seen, his looks the most spotless for some reason.

Irrespective of colour, all chef’s coats are double-breasted to provide a layer of protection against heat and the inevitable hot splashes. Below, we wear loose pants so that our skin can breathe. The material is thick cotton—its texture reminds me of the karate uniforms of my childhood.

It was in the CP café where I first worked that I realised how kitchen hierarchy spilled over into sartorial rules. When I joined, I was given a green coat while my team wore black. That bothered me. I felt lucky that I didn’t have to start my journey in the normal way: chopping kilos of onions before getting within touching distance of a cooking range. But I still wanted to be dressed just like the men and women I was supposed to lead.

Gradually, I began owning the word ‘cook.’ (In general, I call myself ‘khansama.’) To be fair, the word ‘chef’ is derived from ‘chief’—it is true that not everyone can attain the apex of that hierarchy. The chef not only cooks, but also runs the establishment.

I’m not offended by the word ‘consultant.’ I help restaurants design their menus, share recipes and train the staff. I’m a gun for hire: I complete a project and move on to the next one. It is a relatively new line of work in the industry, of a piece with the rise of the gig economy more generally. I don’t know if there’s much point to hankering after the top position, which creates strange expectations. One contestant who auditioned for the 2019 edition of Masterchef India said his only motivation was to become a “celebrity chef”: he simply wasn’t interested in chopping onions or potatoes. (The judges, predictably, did not find this inspiring.)

Someone like Chef Bhasin has always been proactive about learning from home cooks and platforming them. He tells them—you cook and serve the food, I will work on cost and all the other overheads. ‘Instagram chefs’ and food influencers can sometimes lose sight of how big the leap of faith is between recreational and professional cooking. I’ve been dismissed often enough as a ‘TV face,’ which is narrowly true. But I’ve done the tough stuff too, which didn’t make it to screen. You don’t get likes and hearts for completing double shifts and catching up on sleep in cramped hotel bunkers; for cooking tirelessly and not even getting time to feed yourself.

Professional chefs need to control cost, reduce wastage and serve butter chicken like it is an art piece. They need to have a head for science, not only so that they can do all the magical stuff our grandmothers did, but also replicate it day after day. You know the joke about how you’ll call your mother to ask her how she makes one of her perfect dishes, and she’ll just say, ‘Wait until the onions start smelling good, now take a small pinch of this and a big pinch of that’ and other completely unhelpful things? A chef must have the talent to cook that instinctively, and also possess the knowledge and ability to explain what they’re doing.

In 2018, my friend Abu Sufiyan and I conducted a pop-up for about 50 guests in Old Delhi. We were serving the heritage dishes of Shahjahanabad with recipes based on family trademarks and oral histories. There was Dilli biryani, chicken qorma, mutanjan, zarda, different kinds of rotis. Later, one of the influencers who attended texted Abu saying that food was good but “not MasterChef level.” He basically meant our plating was not fancy enough. Sir, if you’re reading this, here’s the reason why: you came to a pop-up that was meant to celebrate Ghalib’s birthday. A plated dish of heritage cuisine would have just killed the vibe. Context matters.

There are home cooks like Sherry Mehta who have fought all sorts of battles to get their food the recognition it deserves. Sherry runs a delivery kitchen called Kanak by Sherry, staffed by women, which serves delicacies from undivided Punjab. You may be familiar with her, since she’s now appeared on several TV shows. Sherry still contends with the glass ceiling in professional cooking. She told me she’d often break down in the face of the recalcitrance of kitchen staff, who’d only take orders from the male head chef. (The hot kitchen was and remains a hotbed of casual misogyny. A chef friend of mine had to quit working for a popular brand in Pune after being at the receiving end of sexist behaviour from the property manager. I can’t imagine how many other stories like hers are out there, untold.)

Tight Ships

herry told me that once you open a restaurant or a food business, people assume that you are suddenly swimming in money. What can I tell you about the margins in the restaurant business that won’t bring tears to your eyes? There’s so many balls to juggle, and they often have nothing to do with the quality of your food: budgeting, salaries, vendor management, delivery app integration, offline and online promotions. In many cases, you’re just barely staying afloat and sane.

We don’t spend irresponsibly—we can’t. It’s simply common for restaurants to have to cut costs, even as we continue to serve “best-in-class” food. To do this, we repurpose ingredients, change names, tweak the plating. A simple minced meat for seekh kabab has probably turned up on your plate as qeema with pao; in little tikkis that go with your drinks, egg-washed and fried; resurrected in the qeema samosa. We change up sauces and condiments all the time to make this stuff seem different: those are the smarts a chef needs.

We do draw the line at picking up food dumped in the trash can. Well, most of us do.

But there’s so much unpredictability in this business. One delivery of bad or tampered ingredients, and a whole meal service is ruined. That snowballs into angry reviews and customer complaints: good food goes all the way up, they say, but bad food attracts a lot more negativity. A rough day can make or break a small business like Sherry’s. She’s had days when she’s had to order her mutton online for ₹1200 a kg because her regular vendor didn’t come through. That means the menu price of the dish was literally half her cost. Almost every restaurant you have ever been to has taken that hit.

If you’re an aspiring chef, please be clear-eyed about this before entering the business. You will be paid poorly, because the restaurant’s balance sheet is likely to be bleeding. The average salary of a head chef in a Delhi restaurant is between ₹40,000-₹60,000 a month. Line chefs and sous chefs who have just started out make much less—often about ₹15,000-₹30,000. A consultant like me often hits financial roadblocks. You’ll hear the usual platitudes: “We will stick together, so you should do this project for less!” “Oh, but you are giving us only so many dishes!”

What keeps us in business, then? Love.

One restaurant in North Delhi refused to pay me because I had to go to Mumbai to shoot for a few days. “But we didn’t even use all your recipes!” they said later. Another restaurant conveniently skipped paying me a whole instalment of my fee because I quit after giving notice for 25 days and not a month. Covid has dealt the latest body blow to the eating-out business. A couple of restaurants I was in talks with expected me to work for free because, well, “Covid.”

What keeps us in business, then? Love. Take Osama Jalali of The Mughal Plate, whom I mentioned earlier. His is a celebrated name in Rampur and Delhi heritage cuisine. He calls himself a bawarchi and tells great stories. Osama isn’t a trained chef. He prefers to trust an instinct honed over years of careful observation and improvisation.

He told me that younger chefs don’t have time for the old techniques. “Isse hamaara haath kharab ho jayega,” they say. It will spoil our style. On his part, Osama Bhai said, “Aur hum aap jaisa nahi banaa sakte hai.” I can’t cook like you all do. It’s his way of saying that you will never find a smidge of tomato ketchup in his butter chicken and that his dal makhani will necessarily be cooked over eight to ten hours. But the beauty of his art is that he knows that there’s a line between creative integrity and rigidity.

When the Jalali family started cooking, they were just another Muslim family trying their hand at the catering business, unconcerned by labels like ‘chef’ and ‘home cook.’ They operated on negligible margins and never compromised on ingredients and cooking time. Clients would not even want the family name to be displayed on tissue papers and food packets. Now, Osama said, “the same people come to us and ask for our title. You don’t have to cook, they say. Just let us use your name.” Now there’s a compliment that goes beyond titles.

In the end, it’s not about how many times you’ve made the same dish but about how you make it every time. It’s not about getting bothered by one negative comment, as Chef Vicky Ratnani says, but about being consistent and passionate. The key in this business is to keep experimenting and pushing your boundaries, bit by bit. I’ve tried various things to spread my gospel—I’m now an author and a podcaster too, for instance. They say love takes you places. My love for food definitely has.

Sadaf is an author, chef and podcaster. When not cooking and writing, you will find him taking photos of the city and people.