Chapter Six: Pointing Out

t was a secret informer who put the Delhi Police on to the man who would become A3.

Those are the precise words in the court documents. Wazid Kazai, a prosecution witness who’d turned hostile, helped the police identify a suspect named Mohammad Noushad, who lived at Delhi’s Turkman Gate. The police surveilled his house for a few days. Then, when they were looking for Noushad at the steps of the Jama Masjid, they received the tip from a “secret informer” who told them Noushad was at New Delhi Railway Station. They caught him there, and he became A3; a fellow passenger, Mirza Iftikhar, became A4. Both, the police claimed, were boarding the Varanasi Express to go to Gorakhpur.

With the help of their disclosure statements, the police further claimed, they were able to arrest Ali (A6) and Latif Waza (A7), not from Nepal, but from a Hotel Budha, in Gorakhpur, on 16 June, and Mirza Nissar (A5) from a hotel in Mussoorie the following day. The police claimed that on the very day they brought A5 to Delhi, he pointed out to them the house of Maqbool Shah (A8), from where the police recovered a stepney of the car used in the bombing. A month had now passed since the bomb went off.

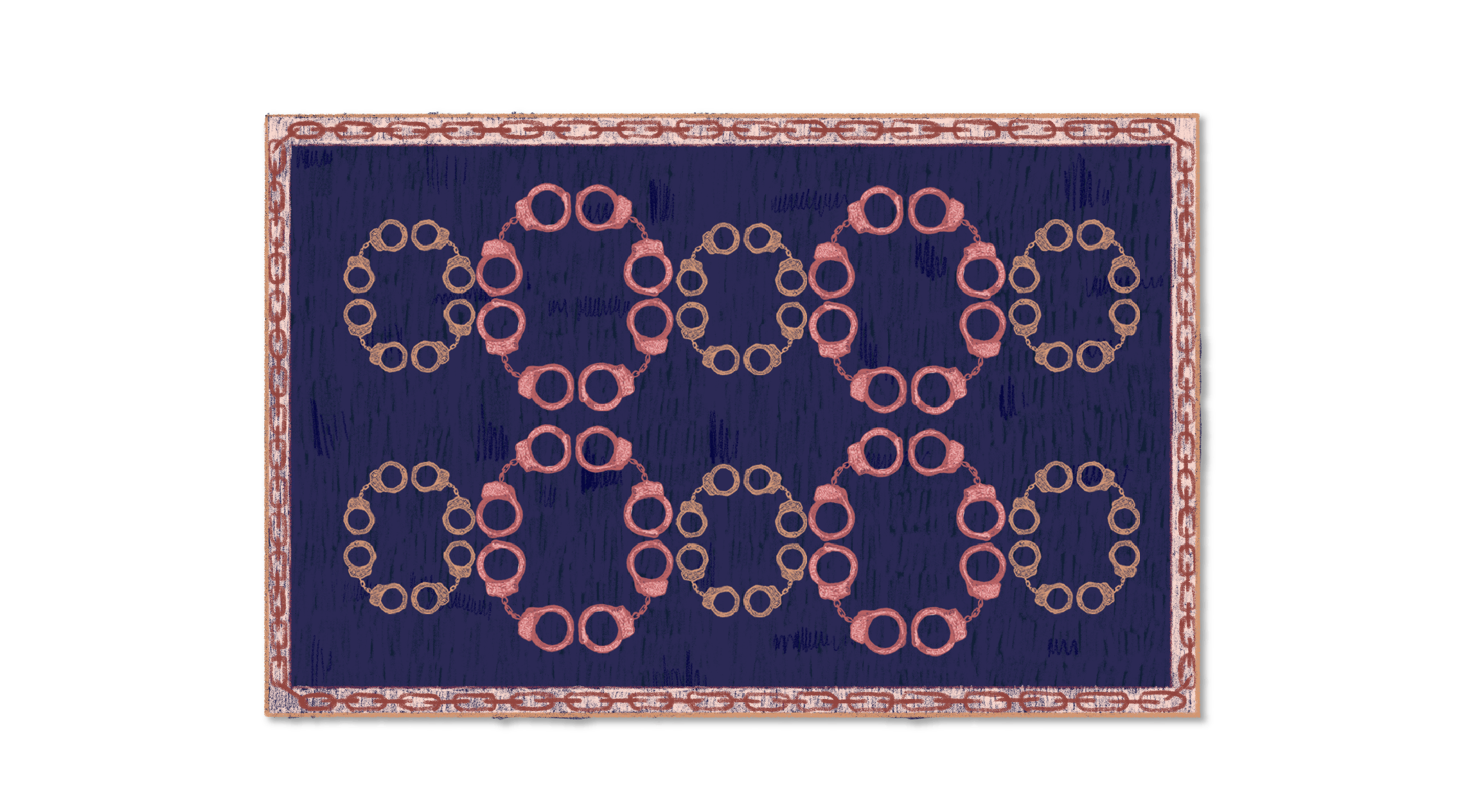

The police claimed to have recovered something or the other belonging to almost all of the accused: an assortment of evidence to link each to the other, like the handcuffs that had chained the men together in Nepal. Ali, Latif and Nissar, whom the police had picked up in Kathmandu and illegally detained and beaten for days, became suspects arrested from Gorakhpur and Mussoorie, on different dates, by different cops.

In his own statement, A4 Iftikhar, who is also Nissar’s brother, claimed that he was arrested by the police from his room in Delhi’s Bhogal neighbourhood between the night of 27 and 28 May. For 18 days, Iftikhar said, he had been kept in illegal confinement at the Special Cell premises in Lodhi Colony.

Atul Nath, whose car was stolen and used in the bombing refused to depose that Noushad, Ali and Nissar had stolen the car. Nath was not the only witness declared hostile. The prosecution’s case-building was tenuous enough for the judge to note that the matter rested “solely on circumstantial evidence.” Reading through the case papers this year, I learned that some of the consequential evidence relied on what’s officially described as “pointing out.” In the police’s accounts, someone or the other pointed out places where the suspects allegedly purchased material used in the crime, or ran an errand in connection to it.

The prosecution claimed that Ali and Noushad had pointed out a place where fake number plates were made which were used on the bomber car. The investigating officer, a man named Paras Nath, was himself present. One Asgar Ali who ran such an enterprise, signed the police memo at the time. The police did not present Asgar Ali in court, nor did they present any independent witnesses to establish that such an exercise had actually taken place.

In another instance, the police claimed that Ali, Nissar and Noushad pointed out “the place near Lal Mehal ‘Khandar’” and a “place under Lodhi Fly Over” from where they recovered the original front and rear number plates of Atul Nath’s lost white Maruti. On the same day, the trio allegedly pointed out a place “behind bus stand, Nizamuddin ITI, Arab Ki Sarai,” where the police recovered a duplicate key that was used in stealing the Maruti car. Mohammad Rizwan supposedly prepared the key in question. He turned hostile in the witness box. No independent witnesses appeared.

The judge held that these were not incriminating circumstances against Ali, Nissar and Noushad.

But Sumit Kumar, owner of the Dulhan Dupatta store in Lajpat Nagar, had seen the bombers parking the car in the Lajpat Nagar market days before the blast, the police claimed. Kumar initially stated he wasn’t even present when the police visited his shop on 18 June. The prosecution declared him hostile at this, but on cross-examination he turned out to agree to almost everything the prosecution suggested.

Kumar identified Noushad with certainty, Nissar “with some degree of doubt” but “could not identify the third accused,” Ali, “at all.” Oddly, this worked against Ali. Kumar’s initial refusal to admit that he’d met the police when they came to his shop was registered as “confusion” in the court. His failure to identify Ali convinced the court that Kumar’s testimony was unbiased: “Had this witness nurturing any grievance against the accused persons (sic) he must have identified the third accused as well.”

The next pointing out, on 19 June, was a shop at which, police claimed, the 9-volt battery had been soldered. The shop owner confirmed that he’d fixed “the two wires on terminals by soldering which he got done by his employee and took Rs. 5/− on the job.” To the court, this owner confirmed that A5, Nissar, was one of those two people who had come to shop. “The witness also pointed out towards A6 and stated that he was the second person but he was not sure about it,” the trial court judgement reads.

The police also furnished the claim that Ali and Nissar went to a shop called Imperial Gramophone in Chandni Chowk to buy a “Jayco alarm piece” for the bomb. The owner of the shop was declared hostile by the prosecution after he failed to identify Ali and Nissar, and the police produced a salesman who they claimed made the actual sale. The salesman instead identified Latif as the customer. “However,” the judgement reads, “perusal of the pointing out memo reveals that both these accused persons whose name find mentioned (sic) therein had led the police team to the said shop in pursuance of their disclosure statements.” In other words: the court chose to rely on the pointing out memos despite the doubts that were raised during the witness testimonies.

Ali told me that “no pointing out to the police ever happened.” Or, at least, he didn’t participate in any such pointing out exercises. “It was all made up,” he said.

Yet, at the time, the defence did seemingly little to push back, and several lawyers, as well as a judge, told me that the proceedings reflected poorly on the accused’s lawyers. Anwar Khan, the lawyer who used to work with Tufail, agreed that they could perhaps have done better in cross-examining the prosecution’s witnesses. “But it isn’t always that simple,” he added. “Sometimes the judge restricts you from suggesting”—presenting alternate theories to explain a particular event—“and then uses that against you in the judgement.”

Anwar was careful not to say that this was what happened to them in this case. As the facts stand, the defence called only two witnesses, who didn’t make much of an impact on the trial. I asked Anwar why this was so. He suggested that the fear of getting entangled in the judicial process could deter anyone, no matter how intimate they were with an accused person. Besides, “Merely calling a witness to support our theory doesn’t do any good unless their facts are backed by documentary evidence. We must not have found that to be the case, otherwise we would have called more people,” Anwar said.

The whole case had turned on the information that came from the interrogation of the men who became A9 and A10. On 2 June 1996, the Ahmedabad Anti-Terrorism Squad arrested Javed Khan and Abdul Gani, and informed the Delhi Police that they’d been involved in the Lajpat Nagar case.

The backbone of the police theory—against which they checked off all this circumstantial evidence—was Javed Khan’s disclosure statement to the Gujarat ATS on 1 June and his confession to a Jaipur magistrate dated 19 July. The police’s timeline of events and its list of dramatis personae in the case draws from these. Javed Khan was formally arrested by the Delhi Police only on 26 July.

As of this writing, most of what Javed had claimed in that long-ago confession has fallen apart. All but two people—Javed himself and Noushad—arrested as a result of Javed’s confession have been acquitted for lack of evidence.

Javed’s 2013 appeal petition in the Supreme Court raised questions over the voluntary nature of the confession. The petition contended that the “nine weeks delay in making the arrest and confession had not been explained at all by the prosecution.”

Chapter Seven: The Playbook

n the years before and after the Lajpat Nagar bombing, the Special Cell of the Delhi Police earned a certain infamy in dealing with terror cases. A 2012 report by Jamia Teachers’ Solidarity Association titled “Framed, Damned and Acquitted: Dossier of a Very Special Cell” listed 16 cases in which Muslim men accused of terrorism by the Special Cell had been acquitted by the courts, but only after losing years, and sometimes decades, of their lives in jail.

“It is when you place all the cases side by side that you notice how remarkably similar the script is in all the cases. The terror modules are busted in precisely the same manner every time, the accused are apprehended through identical means each time; even the procedural lapses in the course of the investigation and operation are similar!” the report noted in its preface.

The Lajpat Nagar case was the second listed in the report. The first case is tantalisingly similar: an allegation that Kashmiri militants had sneaked into the capital with the intention to commit acts of terror. But in that case, no bombing had occurred, and the accused had documentary evidence to prove that the Special Cell had illegally detained them before the official dates of arrest presented to the court.

In one instance from a 1992 case, the police claimed that one of the accused had “led the police to a pistol buried in a pit near a tree.” In the 1996 Lajpat Nagar case, the police recovered “RDX and five timers” from a pit near an “anar” tree at Farida Dar’s house, a charge for which she was convicted and sentenced, even though she was cleared of the charge of conspiracy in the blast itself.

In such cases, the nature of trial court justice makes some convictions likelier than others. In terror cases, at least some of the accused are almost always convicted, giving these crimes names and faces for the public record. “One can’t indefinitely delay the judgement, even if there are some lingering doubts,” a UP-based civil court judge told me, on condition of anonymity. “You go with your gut, and hope to sleep peacefully at night. There is always the higher judiciary to overturn a wrong judgement.”

efore the charges were brought to trial, when Ali was in Jaipur Central Jail, his mother died in Kashmir. He got the news in a timelier manner than usual. Ali told me that it was difficult to get mail in Jaipur, and letters were passed on to the prisoners after they’d been checked by the CID, often months after they had been received. But this one was written in red ink, and the jail officials may have sensed it was important. It hadn’t come from home—his family had decided not to tell him by mail—but from a woman he’d been friends with in better times.

He cried and was consoled by his co-accused and by the others in the ward, who helped him organise a funeral prayer. In the Dausa court, a few days later, he was denied parole. Latif’s family came to that hearing, unusually tight-lipped, bearing the burden of the tragic news, but he was able to relieve them of the duty. “They didn’t say anything to me, but I told them I know.”

In 2005, when an uncle passed, his father wrote to him with the news. To a scheduled hearing the following day, Ali took a handwritten request for parole. His fellows in the ward had laughed—“It was out of pity, knowing that such a thing would be futile”—and Farooq Khan, the most educated of the lot, expressed his doubts, even though he said the letter was well-written. But Ali took his chance, and was rewarded. The judge overruled the public prosecutor’s objections, and Ali went back home to Kashmir for the first time in almost a decade.

The journey took two days. Ali was taken to three different police stations before he was escorted to his uncle’s house in Habba Kadal.

“There was a battalion from the armed forces, apart from the police,” he remembered. “A terrorist had come to visit.” He was allowed inside the house in chains, surrounded by police. He met his father, sisters, cousins, neighbours from Hassanabad, people he recognised because of the family resemblance to others he’d once known.

“Can’t explain that,” he commented. “Such a feeling. My father had told me not to cry for the sake of my sisters, so I didn’t but they couldn’t stop crying. I left them smiling.”

His request to visit his mother’s grave was denied, and as evening fell, he was taken back to Sher Garhi police station. The next morning, a police escort took him back to Jammu, where they would board the evening train to Delhi. When they broke for lunch, some of the policemen shared the chicken Ali’s sisters had cooked for him at his request. Soon, he was back in the high-security ward in Jail Number 2 at Tihar.

“Over the next five or six months I was frustrated,” he remembered. “I had gotten into the atmosphere of home, and back in Tihar, I regretted that visit.” But he kept those thoughts to himself, and overcame the torment over time. It was enough for him to apply for parole again, which was granted twice: in 2006, to pray at the imambara at Hassanabad for another deceased uncle, then in 2007, when his father was very ill. On the 2006 visit, he was allowed to pray at his mother’s grave. On the 2007 visit, he kept his head bowed in front of his father. He found he couldn’t look straight at him. “I asked him for forgiveness,” he said. “I thought I should do it while he still had the time.”

Between 2006 and 2008, there were multiple attempts to move the case along: a high court order to complete the trial in six months, then another asking that the hearings be expedited, and the trial be concluded in one month. Meanwhile, Ali’s lawyer tried to get it transferred back to S.P. Garg, a judge who’d already heard the case at length. A court order signed by Judge S.K. Sarvaria, to whom the matter was transferred out, suggested that Garg had even partly dictated a judgement in the case.

When the defence petitioned to have the matter sent back to Garg, the prosecution lawyer initially agreed to the request but then opposed it. This scenario played out at least twice more. Ultimately, three different judges heard at least part of the final arguments in the matter.

An order to hold daily hearings in the case was never upheld, thanks to—from what I could discover—reasons that included a lawyers’ strike, leave of the prosecution lawyer, the judge being occupied elsewhere, public holidays and Friday prayers for defence counsel.

Chapter Eight: The Judgement

y the time Ali’s lawyer finished his set of final arguments, it was February 2009, and a new judge, M.K. Nagpal, was on the bench. The defence concluded its arguments in April, but then, much to their chagrin, the prosecution moved an application to summon or recall some of the witnesses, including ACP Prit Pal Singh, the officer who’d been waiting for the Kashmiris in Gorakhpur when they crossed over from Nepal; and the investigating officer, Paras Nath. Singh had not appeared in court until now, and none of the memos on record had his signature. By the time four more witnesses deposed, another judge had taken Nagpal’s place.

September 2009. The case was transferred yet again, back to S.P. Garg, whom Ali’s lawyers had wanted on the job all along. Garg had already heard arguments on 22 dates, the transfer order noted. In his court, the final arguments—at least some of which he had likely already heard years earlier—wrapped up by mid-December.

“It was mental torture,” Ali said. Years later, the disgust he felt at the waiting and repetition was still fresh. “They were doing timepass,” he said.

On 8 April 2010, Judge Garg announced his order in the case. He acquitted four of the accused, announcing their names first: Mirza Iftikhar, Latif Waza, Syed Maqbool Shah, Abdul Gani. The rest of them, including Ali, had been convicted. The sentencing was set for 22 April.

On that day, Farooq Khan and Farida Dar were called up first. They’d been acquitted on charges of conspiracy, but convicted for possession of arms and ammunition, based on the Delhi Police’s recoveries and statements. But they had already completed their prison terms during trial. Javed Khan was up next: he got life. Ali listened keenly for his own name, but he, Nissar and Noushad were not called. From a distance, he saw his lawyer approach the bench, and the judge speaking to him. He figured then that they’d been given the death sentence.

“The judge said that they had behaved well throughout the trial and that he was very saddened to pronounce death for the three of them,” Anwar Khan remembered. Ali approached the bench through a posse of lawyers, some disappointed, some celebrating his death verdict. “You have been held guilty under multiple charges,” Garg told him. Ali, fighting for calm, asked if he could call home, but the request was denied. “‘Well-behaved’ convicts sent to the gallows,” read a headline the next day.

Back home, protests broke out. Both factions of the Hurriyat, Kashmir’s big-tent separatist organisation, issued calls for agitations, and said Indian courts were taking a “biased approach” to Kashmiris. Yasin Malik, leader of the Jammu Kashmir Liberation Front, also launched an agitation. In Srinagar, youth protested for Ali and Nissar, and pelted stones. Their names had been known for some time. In 2004, during talks with the Union government, the Hurriyat, then headed by the prominent Shia cleric Molvi Abbas Ansari, had forwarded a list of Kashmiri prisoners whose release they appealed for. Delhi had approved a similar list before, but this one was turned down. An Indian Express report from the time states it was strongly opposed by the Intelligence Bureau and the Delhi Police.

Ali had mixed feelings about the politics around their case. “Molvi Abbas Ansari threw my family out of his house when they had gone to seek his help for me,” he claimed. Another prominent Hurriyat leader, Abdul Gani Bhat, allegedly told his father, “‘But then, why did they have to carry out the blast?’”

“As a father, this is my moral responsibility,” Haji Sher Ali Bhat told a reporter after the conviction. “To fight till our ward gets justice. We will definitely challenge the verdict in the higher courts.”

Chapter Nine: The Appeals

n Tihar, among acquaintances that included history-sheeters, hardened criminals, militants, and an elderly Delhi landlord, Ali had developed a friendship with a Kashmiri of some note: Syed Abdul Rahman Geelani, the professor accused of orchestrating the attack on the Indian parliament in 2001. “He was a very good man,” Ali said of Geelani, who was acquitted of all charges, and died in 2019.

After his acquittal, Geelani became a lifelong activist for people he believed were wrongfully imprisoned, and allied with a number of institutions that offered legal help to such detainees. He enlisted Kamini Jaiswal, a well-known lawyer, to fight the case of the Lajpat Nagar blast accused in the Delhi High Court, without them having to pay for her services. She forcefully presented the case, hammering home the discrepancies that the prior defence team had been unable to nail in the trial court.

The judge this time took note of the inconsistencies in the prosecution’s approach, and castigated the police’s investigation. “The prosecution suggests that an egg has been made from an omelette,” Justice Ravindra Bhat said in court, in Ali’s memory. “The reverse is possible, but not this.”

The prolongation of the final arguments had been “entirely avoidable,” he noted in the judgement. “As regards A-6....save his arrest—a neutral circumstance ipso facto—no other circumstance linking with the crime has been proved,” the judge noted. Noushad’s death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment, and Nissar and Ali were fully acquitted. It was November 2012. Ali had spent more than 16 years in jail.

He hoped that vindication in Delhi meant that the pending charges against Nissar and himself in the Samleti bombing case would be swiftly disposed. Farooq Khan, who’d served the seven-year sentence handed down to him in the Lajpat Nagar case by the trial court, was a co-accused in Samleti, too. So were Latif and another man named Asadullah, who’d been acquitted in the Lajpat Nagar case by the trial court in 2010.

“But they were cruel to us,” Ali said. “After losing so many years, they took seven more from us.”

The Samleti case was still languishing in the lower judiciary in Rajasthan. Tufail represented the accused here as well, using some local lawyer as proxy on days when he couldn’t show up from Delhi. Although the bombings happened within a day of each other, and caused almost the same number of fatalities, the Samleti blast had been an afterthought in the national media compared to Lajpat Nagar. Media attention withered, and the men settled in for the long haul again.

They were taken to Rajasthan a few days after their acquittal by the Delhi High Court. The spectre of the death sentence had been lifted, but only for now. They were still prisoners of the state. A few weeks later, in February 2013, they were in Jaipur Central Jail when Afzal Guru was hanged for his involvement in the 2001 Parliament Attack. “We were having lunch when we heard; we didn’t finish.”

They were still there in May 2014, when the Bharatiya Janata Party swept general elections in India, and Narendra Modi became prime minister. The spike in communal tension this caused pierced through the walls of the jail. “You could see the difference in the behaviour of the people,” Ali said. “Inmates, policemen, jailers, everyone behaved differently.”

The newspapers began to report stories of the lynchings of Muslim men in various states across India, murdered amidst frenzied accusations of beef-eating and cattle smuggling. Ali’s years in jail had taught him that individuals could be humane to each other if they weren’t reduced to their religious identities. Experience had taught him to judge men by character. But he saw, now, that he would have to be more cautious.

On one terrible night in June 2016, during Ramzan, he was woken up by his cellmates. One of his many cellmates who secretly possessed a mobile phone had received a call from Kashmir. Haji Sher Ali Bhat was dead.

I didn’t have such a strong reaction when my mother died,” Ali recalled. “This time I couldn’t bear it. It was a very big trauma for me.” His father had lost everything he had built pursuing freedom for his son, and had been unwell for a long time. For years, they’d communicated surreptitiously though Ali’s cellmates with phones. The first time had been in 2012, when Ali got wind of the news that one of his cellmates had gotten hold of a 3G phone, one that could make video calls. “I had seen lawyers, policemen with big new phones, but I didn’t understand it. I didn’t know what a video call was, or even an SMS.” His memory of the outside world had become an archive, only useful for references of the past.

Ali got word to his brother to get hold of one of these new-fangled phones. When he did, the right-hand man of a dreaded gangster from Uttar Pradesh generously lent Ali his device. “I asked him to dial the number because I didn’t know how to do it,” he remembered. “I was wearing an undershirt and a lungi, sitting on the floor with my legs folded.” It was the first time he’d been able to speak to his father from prison. It was possibly the last happy memory they made together.

“I’d been very close to him since childhood, more than any of my other siblings,” Ali said. “That bond only grew as I got older. He would call me, and no one else, to polish his shoes. If he needed someone to accompany him somewhere, that would be me. If, among our brothers, someone needed his ear, they would go through me.”

In September 2014, Ali had been convicted by the trial court in Dausa and sentenced to life imprisonment along with Nissar, Latif and Asadullah. Farooq had been acquitted. Nothing linked them to the blast except the ordeal of their accusation in the Lajpat Nagar bombing.

They filed an appeal in the Rajasthan High Court. They had reason to be hopeful: a high court had acquitted them once. The years that followed were the hardest of all. Things moved slowly in the Rajasthan judiciary. The roadblocks in the process were accompanied by the growing hostility of the individuals he now found himself encountering in the system. All the while, he was reading about India’s transformation in the papers: the insults, the assaults, the lynchings.

He held on to his faith, devoting more time than ever before to reading. “My father would send me letters with verses of the Quran and their meaning,” he said. Perhaps as a way to feel closer to his father as well as to the divine, Ali began to write the Quran by hand. A friend and fellow inmate named Ankur Pandya would help him replenish his stationery supplies in jail. The paper Ankur procured was not ordinary stuff, Ali told me. It was good paper, appropriate for the verses from the holy book. Over a period of almost four years, he copied the Quran out twice.

Ali and Nissar are both Shia, and both observe the rites of Muharram. “When you are free, outside, you don’t really get the meaning of the sacrifices of the martyrs of Karbala,” he explained to me. During the first ten days of Muharram, believers weep and beat their chests to the chanting of marsias, elegiac poems for the martyrdom of Hussain, the grandson of the prophet Muhammad, and his companions at the hands of the tyrant Yazid. But it is also a time of reunions and meetings, of elaborate meals and endless rounds of tea in the company of loved ones. “In jail,” Ali said, “you really understand the magnitude of this tragedy and you feel that your tragedy is not even a speck in comparison.”

When they were in prison, Ali and Nissar both performed marsia during Muharram. On many occasions, he remembered, Sunnis and even Hindus slowly joined them, beating their chests. It became a congregation of the grieving. “I don’t know why they would join or what they were thinking,” Ali said. “But we all mourned.”

Chapter Ten: A Free Man

n February 2019, militants attacked an army convoy in Pulwama in Kashmir. A few days after the attack, some prisoners attacked a Pakistani inmate named Shakirul. “They told him, ‘There is a good movie playing,’ took him to the television room and hit him on the head with a stone wrapped in a blanket,” Ali said. “He must have died instantly.” (Prison officials said that Shakirul was killed during a brawl over the TV’s volume.)

Ali began to fear physical harm, growing suspicious of the hardened prisoners. It chilled him to recall that just a few days before Shakirul was killed, a man named Kanhaiya had tried to hold him in a chokehold. Kanhaiya had laughed it off and said he’d just been playing around.

Then, in July 2019, during an otherwise routine hearing, Justice Sabina verbally reprimanded the prosecution for the lack of merit in Ali and Nissar’s case. Over the years, benches had changed, and prosecution and defence had both logged uncounted hours of arguments. The matter was saturated. On that day, seemingly more out of irritation than anything else, the judge decided it was time for a verdict. At the conclusion of the day’s arguments, she said she would hand down judgement within a month.

Kamini Jaiswal, who represented Ali and the others in appellate hearings, hadn’t been in court that day, and Ali was, by this time, without hope. He shaved off all his hair. He had stopped exercising and put on some weight. But just a week or so later, on a Monday evening, Nissar came looking for him. Ali had just said his prayers, and was feeding birds near his cell. “I saw Nissar making weird gestures, but I didn’t give him any attention,” he remembered. “I continued to feed the birds.” The gestures gave way to swearing, and Nissar hugged Ali when he came closer. “We’ve been acquitted,” he said. They screamed and cried. Nissar, Latif, Asadullah and Ali were all free.

In the judgement, Justices Sabina and Goverdhan Bardhar noted that the only link between them and the blast had been Javed Khan’s confessional statement. “Javed has not referred to the involvement of the said accused in the present bomb blast case”—it baldly stated. No legal maze, no convoluted arguments, no weighing of doubts and circumstance.

Word had reached his family in Kashmir and one of his brothers had arranged tickets for Iftikhar, Nissar’s brother, to travel to Rajasthan the same day. He reached Jaipur Central Jail at 11 in the night. He was turned away as the jail hadn’t yet received the order, and told to return at 5pm the following day. On Tuesday, the order came earlier than expected. Ali and others distributed their clothes, withdrew their money, and said goodbye to their fellow prisoners. It was a few minutes past 5pm when they stepped outside. They saw a press reporter waiting for them. But they only wanted to see Iftikhar, who at the time was sleeping off the exhaustion of his rushed travel in his hotel room.

“We were worried. We started to have negative thoughts,” Ali said. “Mob lynching was on my mind.” His fear and anxiety heightened when he saw a jeep arriving with five-six well-built men. They called Iftikhar from the reporter’s phone again and again until he answered. The burly men passed them by: they were there to meet someone else.

Iftikhar arrived in an auto at last, and took them to the office of the local Jamaat-e-Islami, which had been a source of support in jail to Ali and the others. They’d helped to install ceiling fans in the high-security wards some years ago; they also visited on Eid and led congregational prayers on Fridays. The men booked a taxi to Delhi, from where they would fly back home. “But till we reached Delhi, I kept tying my shoelaces,” Ali said. “I was afraid of mob lynching. I thought, if anything happens, the least I can do is run fast.”

In Delhi’s Zakir Nagar, S.A.R. Geelani was awake when they arrived at two in the morning, and waiting to greet them. Ali’s family, also awake, got him on the phone. “Shave,” Ali’s brother commanded him. “Don’t come here with all that beard.”

He couldn’t sleep at all that night. Geelani handed him a shaving kit and showed him to the bathroom, which Ali littered with cigarette ash. “We smoked so many cigarettes at that house,” he told me. “Geelani sahab didn’t have an ashtray. I asked him if his wife was at home. She wasn’t. I told him he was going to get into trouble with her.”

In the morning, Geelani served them all korma and naan. Ali swears that he hasn’t ever had a tastier naan.

Their flight to Srinagar was at 11am. Before they left for the airport, the others went to the neighbourhood market. Ali stayed back, nervous about venturing outside. He didn’t want to push his luck.

When they were finally in the air, he had a dark thought during some mid-flight turbulence. “‘What if the plane crashes?’ I was thinking. I prayed to God: ‘If I have to die after all this, at least wait until I meet my family.’”

At Srinagar airport, the family’s children had gathered to greet him. They put him on video with the people at home. His brother told him to change into kurta-pajama and meet them at the imambara at Hassanabad. He saw his family, and then went to the graveyard nearby. There, he leapt on his father’s grave, hugged the soil and cried. A video of those moments was posted to Twitter, and then carried by several publications online. Over the next few days, he told his story over and over to reporters, condensing his lost years into a sequence of days and events. The first ten nights were sleepless. It was difficult for him to believe that he was home after all.

“Sometimes, even now,” he told me, “it seems unbelievable.”

Adil Rashid is an independent journalist. He has written for The Caravan, The Wire, PARI and SCMP. Previously, he worked at Outlook.

Corrections & Clarifications: An earlier version of this story said that the police claimed that storeowner Sumit Kumar had seen the alleged bombers park the car "at the spot where the explosion took place." That version could also be read as suggesting that Kumar saw the men park the car on the day of the explosion. In fact, the police claimed that Kumar had seen the alleged bombers park the car in the Lajpat Nagar market days before the blast.

We regret the error.