The small hamlet of Tarawadi is in the Newasa taluka of Ahmednagar district. It is 180 kilometres from Pune, along the highway that connects the city to Ahmednagar. Tarawadi’s relative remoteness may belie a special truth about it. In the early decades of the last century, it was the stronghold of a movement led by the pioneering Jotirao Phule. The Satyashodhak Samaj, the Truthseekers’ Society, was committed to the upliftment of marginalised groups in the face of Brahmin hegemony. In Phule’s own words, these groups were the stree-shudra-atishudra: women, Shudras and communities designated untouchable.

Despite this legacy, and the fact that I spent many childhood vacations in my grandfather’s home less than 100 kilometres away, I had never been to Tarawadi until I began work on my doctoral thesis. My first visit was in August 2021. When I got there, I saw a wizened, bespectacled man in a neatly-clad dhoti waving enthusiastically from the pavement. The 82-year-old Uttamrao Patil is the sole caretaker of the Deenamitrakar Mukundrao Patil Archives and Research Centre, where I had come to collect material on the vernacular, non-Brahmin print sphere.

Mukundrao Patil was Uttamrao’s grandfather. He was the founder and leading light of India’s first rural newspaper Dinmitra, pronounced “deen-mitra,” which loosely translates to “friend of the oppressed.” Mukundrao started this paper in 1910, and published it continuously until his death in 1967.

On the walls of the main room of the centre, I saw hand-painted portraits of Mukundrao. They shared space with Warli paintings and framed photographs of members of the Satyashodhak movement. The two smaller rooms contained a goldmine, at least for a researcher such as myself. Books, correspondence, booklets and pamphlets from the early twentieth century had been carefully preserved. The slimmest volumes were placed in thin plastic folders, and neatly labelled. Titles were written on the cover page in bold, black letters.

As Uttamrao showed me around, he told me about his own journeys to Satyashodhak meetings in far-flung villages to collect the material that was on display. His passion was infectious and his manner welcoming. This attitude was reflected in the physical space, too. Everything about it was approachable, quite a contrast to the rarefied air that accompanies hallowed, city-based research institutions. There was a table, chair, lamp and photocopying machine, with no restrictions on document collection. Students are allowed to peruse even the most fragile material.

Uttamrao is the custodian of a critical legacy, one that has its origins in a time when India’s elite had turned to the print sphere to articulate its ideas of freedom. But these ideas were not a monolith, and people like Mukundrao Patil and Phule were intent on advocating freedom of a different kind. Freedom, to them, meant the liberation of the marginalised from the shackles of illiteracy and poverty.

That is why they often found themselves at odds with many of those espousing the idea of political freedom. For the latter group, for instance, the British were the enemy. But the Satyashodhaks didn’t quite see it that way. Unlike their fellow Indians, the British had opened the doors of education for the marginalised. [1] For Patil, a rashtra—a nation—had no meaning if untouchability and a lack of human rights continued to corrupt the conscience of society.

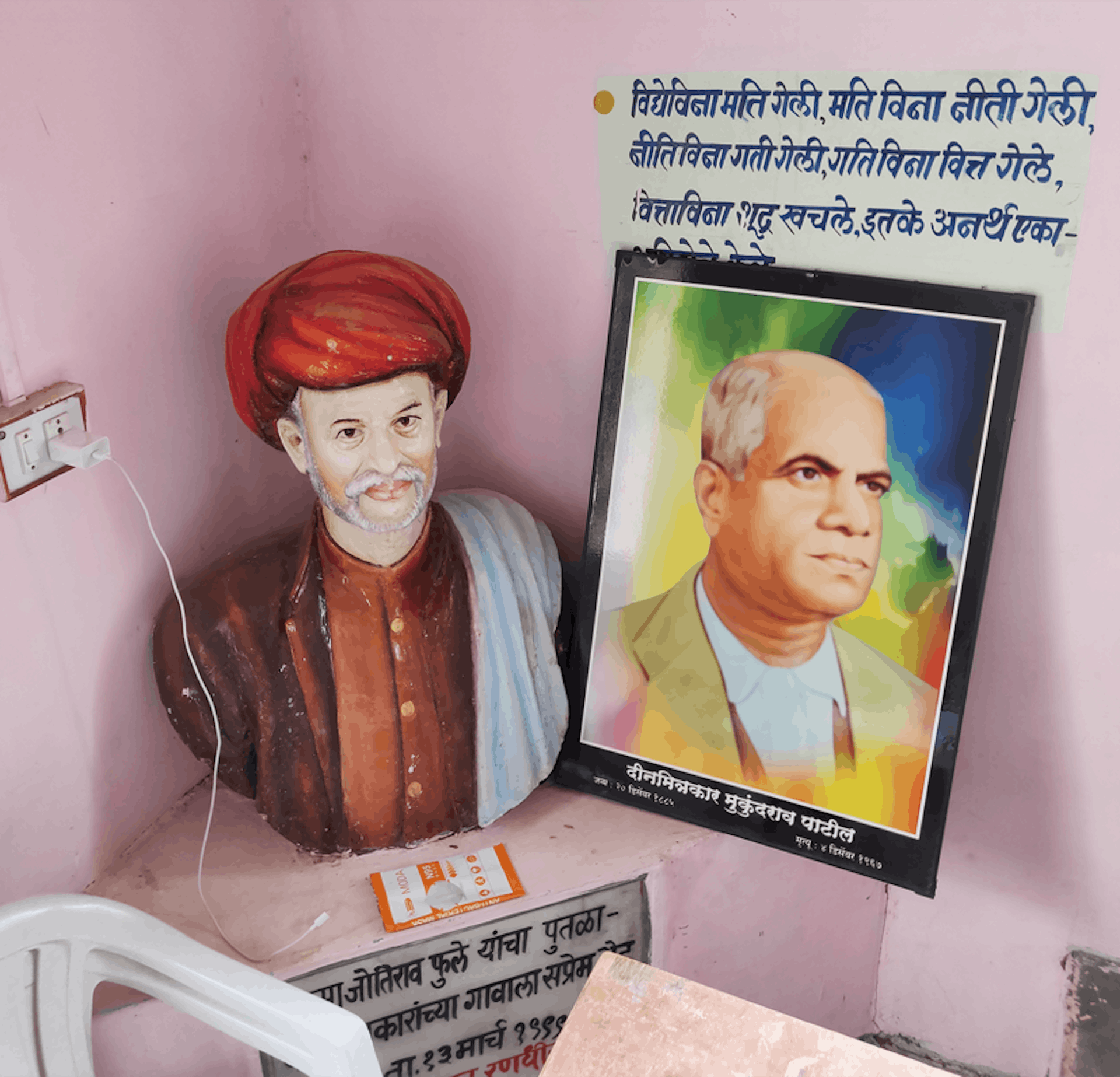

A bust of Jotiba Phule and a portrait of Mukundrao Patil in the main hall of the research centre in Tarawadi. Credit: Surajkumar Thube

That’s why Dinmitra painted a picture of local realities and challenged the narrative of the mainstream nationalist movement. It did this by adopting a unique form: opinion-based journalism in the vernacular. In this, too, it opposed the supposedly objective, fact-based journalism which was being produced in urban spaces.

Patil was one of the last Satyashodhaks to prioritise the social and religious question over the political one. His paper engaged critically with nationalist publications of the time, including Bal Gangadhar Tilak’s famous Kesari and Mahratta, which gave pride of place to writing about Home Rule and community festivals like Ganesh Utsav.

Two decades before B.R. Ambedkar frontally critiqued Hindu texts and Brahmanical rituals, Patil was writing about how the Brahmin priestly class was “Hinduism’s enemy number one.” Himself a non-Brahmin Hindu, he carried forward the inheritance of his father, a close associate of Phule. [2] His Dinmitra was an ally to the most marginalised at a time when enforced untouchability also meant enforced invisibility. Through Dinmitra and his work, he challenged the dominant, conservative idea of what a nation can and ought to be.

Origin

rishnarao Bhalekar, Mukundrao’s father, first met Jotiba Phule in 1868. Bhalekar, then 18, was already espousing views on how “hypocritical Brahmins, under the guise of dharma, con gullible unlettered people.”

Already, at the time, Brahmin-run publications proliferated. One of these was Nibandhamala, a monthly magazine run by the influential Marathi prose writer Vishnushastri Chiplunkar. Chiplunkar often ridiculed Phule in his publication, once calling him “the sorriest scribbler with just the clothing of humanity on him.” [3] In response to Phule’s anti-Brahmanism and his critiques of Vedic traditions, he took sly digs at Phule’s socio-economic background, labelling him a ‘Shudra Jagadguru,’ or Shudra world leader; and a ‘Shudra Dharmasansthapak,’ the founder of a Shudra dharma. [4]

All around Bhalekar, Brahmins were exerting influence and carrying their ideas to the public through print. Reading Brahmin-run newspapers like Lokakalyanecchu and Dnyanchaksu in the Poona library, he grew determined to launch one of his own. This would be Dinbandhu, established in 1877, four years before Tilak launched Kesari and Mahratta.

Mukundrao knew it would be difficult for him to continue running his father’s newspaper in the Brahmin-dominated cities of Bombay and Poona.

Dinbandhu, the first newspaper of the Satyashodhak movement, made a humble beginning with just 13 annual subscribers. By 1880, the number of subscribers had increased to 320. A single issue was priced at four annas. [5] The paper was run out of Poona, and supported by Bombay-based non-Brahmins who were doing well for themselves. Two Telugu-speakers, Balaji Kalewar and Ramayya Venkaya Aiyyavaru, backed Bhalekar’s idea and bought him a printing press for ₹1200.

It was an exciting moment. Before this, it was mostly upper-caste men who had the social and financial capital to start newspapers. The development of a caste-conscious print sphere gave rise to a generation of Satyashodhak writers, editors, poets and novelists. Between 1873 and 1930, approximately 60 newspapers and journals dedicated to the principles of the Satyashodhak movement were established, the bulk of them in the 1920s.

Western India became the first region of the country from which such anti-caste writings emerged: in the years to come, prominent personalities such as Pandithar Iyothee Thassar, Narayana Guru and Bhima Bhoi started writing on similar themes from Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Odisha respectively.

To keep the movement and the paper going, Bhalekar groomed his nephew Ganpatrao, son of his sister Kashibai, to take over after him. Both would organise public speeches in the Mangalwar and Budhwar Peth areas of Poona, where they spoke about Brahmin oppression of the Bahujan samaj.

In 1888, Ganpatrao established his own periodical, one that went by the name of Dinmitra. But this first Dinmitra had to be shelved after Ganpatrao’s untimely death at the age of 27, just five years later. Shortly after, Bhalekar let his inconsolable sister adopt his own son, Mukundrao. The Patil family into which he was adopted in Nevasa, Ahmednagar, gave him his new surname.

Dinbandhu was now facing financial challenges. Bhalekar also ran another publication called Shetkaryanchi Kaivari, or “protector of farmers,” that was struggling to raise funds. All this while, Bhalekar had been on the move, constantly looking out for jobs that would help him sustain his aspirations. It was one of the reasons young Mukundrao never managed to complete his education. In 1910, juggling financial and family-related hardships exacted its toll, and Bhalekar succumbed to a paralytic stroke. On his deathbed, the story goes, Bhalekar made his son promise that he would run the newspaper for a minimum of 12 years.

Mukundrao Patil, a mere second-class dropout, wanted to make good on his promise. But he knew it would be difficult for him to continue running his father’s newspaper in the Brahmin-dominated cities of Bombay and Poona. So he chose to plant his roots in Tarawadi, where he had inherited some 70 acres of land from his father. He bought a printing press with the help of his father-in-law, Ranauji Rawaji Aaru, who was the chairman of the Bombay-based Nirnay Sagar Press.

To officially register Dinmitra, Patil had to make multiple arduous journeys on foot from Tarawadi to Ahmednagar, a walk of approximately 60 kilometres. The only viable means of transport then was a bullock cart, which took up to two days to complete the journey. So Patil preferred to walk, leaving early in the morning since that was the only way he could reach Ahmednagar in time to meet the collector during office hours.

His eldest son Madhavrao Patil wrote later that the Brahmin bureaucracy not only dragged its feet, but created active hurdles, when it came to registering Mukundrao’s paper. Patil was Dinmitra’s one-man army. He wrote columns, approached local merchants and businessmen for advertisements, printed the paper and took them to the post office. His publication was among the first in the country to reach a rural, non-Brahmin population. He is often credited as the first person to introduce the printing press to rural India. He did all this at the tender age of 25.

Ambition

he early Satyashodhaks, arguably, could have chosen to persist with aural and visual forms of knowledge like tamashas, and forms of regional folk music like Gondhal, Jagran and Dashavtar, which reached large audiences, including the unlettered. But the radical potential of the print medium meant that they also ran newspapers, despite extreme social and financial instability.

If Tilak’s Kesari and Mahratta were founded with the intention of disseminating regular national and international news, Bhalekar’s Dinbandhu and Mukundrao’s Dinmitra revelled in a kind of regional specificity. Both publications were informed by their founders’ acute understanding of the quotidian socio-cultural tensions between Brahmins and Satyashodhaks. Journalism did not merely mean reportage for both Bhalekar and Patil. For them, it was about using the print sphere to articulate alternative views and opinions.

Patil did not have any prior experience in reading and writing. After relaunching Dinmitra, he decided to devote more time to the world of print. He taught himself English and learnt Sanskrit from a certain Rev. R.N. Tilak. It helped Patil churn out editorials, novels, a kind of poetry called khanda kavya, essays, short stories and satire. From the very first issue of Dinmitra in 1910, Patil deployed different genres of writings to target the Brahmanical trinity of shetji-bhatji-laatji: landlord, temple priest and colonial servant.

The approach drew readers from both rural and urban Maharashtra. In the first year of Dinmitra, nearly 600 readers read its 3,000-4000 issues. An annual subscription was reasonably priced at a cost of ₹3 and a half-yearly one cost ₹2. Several newspapers were priced similarly, but Dinmitra managed to steadily increase its readership over the years because it was one of the few newspapers espousing the principles of the Satyashodhak movement in this period.

A regular distribution cycle saw the newspaper reach places like Poona, Bombay, Aurangabad, Amravati, Khandesh, Kolhapur, Satara, Sangli, Baroda, Parbhani, Nanded, Jabalpur, Belgaum and Nagpur. When a supporter of the movement moved outside Western India, issues were posted to them. That’s how Dinmitra reached far out places like Lahore, the Andaman islands, Singapore and Sri Lanka.

The rise in stature of this little newspaper from Tarawadi was unexpected. Few would have bet that a publication adopting a non-Brahmin lens, full of opinion columns and addressing a local readership, would be received well. The Brahmin retaliation was almost immediate.

Dinmitra functioned from a makeshift tinplate house built on the dry agricultural land that Patil inherited. Local Brahmins dragged Patil to court for using the land for non-agricultural purposes. Dinmitra was embroiled in several such legal battles, which made it difficult for it to attract advertisement revenue in its formative years. (The first page of an issue normally featured advertisements of hotels, medicines, books, bicycle shops or farmer tool kits.)

From the first issue of Dinmitra in 1910, Patil deployed different genres of writings to target the Brahmanical trinity of shetji-bhatji-laatji: landlord, temple priest and colonial servant.

But Patil forged on despite the troubles. The newspaper became his way of being in the world. Apart from his editorials, Patil also published short stories, poetry and satire in Dinmitra. Between 1910 and 1930, he published four novels, which were initially published in a serialised format in Dinmitra. All of them focused on the avaricious nature of Brahmin priests, exposing their patriarchal and social inferiority complex.

In Hindu ani Brahmin, for instance, Patil argued in favour of hollowing out Brahmanism from Hinduism. The works stressed on how Brahmins conned local kings and businessmen, and corrupted religious texts by injecting their own teachings. Sections of this story came out in parts in some of the earlier editions of Dinmitra. Subsequently, other novels like Holichi Poli, Dha Dha Shastri Parane were published in serialised format in Dinmitra. [6]

To ensure the ideas and work lingered in readers’ minds, the material was published at intervals in more than one print medium. In Patil’s case, they first got published in Dinmitra and were then released as books, pamphlets or small booklets. In the present day, Uttamrao Patil has continued that tradition by editing multiple small booklets comprising Mukundrao’s short stories, novels and speeches. Along with these, Uttamrao has worked tirelessly, along with a few researchers, to publish all the editorials of Dinmitra. [7]

Mukundrao Patil’s writings in the kavya form were equally compelling. In works like Krishna Lilamrut and Shetji Pradhan, the farming community is constantly at the receiving end of oppression by local Brahmins and crippling tax impositions by the colonial authorities, a reflection of historical reality. In both books, the Kulkarni, the hereditary village accountant, dupes indigent, unlettered farmers by confiscating their lands. The books were partially released with the support of an influential, albeit reluctant admirer of the Satyashodhak movement in the early twentieth century: Shahu, the Maharaja of Kolhapur. [8]

Patil’s sustained campaign saw him galvanise support for abolishing the heredity-based position of the Kulkarni and have him replaced by a village accountant who would be selected on merit. In 1915, Patil drafted a petition along these lines with Bhaskarrao Jadhav, a member of the Bombay Presidency Legislative Council.

Patil is said to have published 10,000 copies of the petition from his own pocket. He had these signed by people who supported his crusade and then sent the whole batch to the Governor. [9] His effort did not bear immediate fruit, but it was one of the early precursors of post-independence legislation like the Bombay Paragana and Kulkarni Watans (Abolition) Act, 1950.

Challenge

n 1906, Patil made his first appearance at a major public event. As some Brahmin lawyers and society leaders were complaining that a severe paucity of money was impeding their ability to help untouchable farmers, a young Mukundrao Patil, all of 21, stood up. He retorted: where did the organisers get the money to build lavish temples, then?

To much Brahmin consternation, Patil supported Satyashodhaks who were in favour of converting to a new religion. “My untouchable brothers,” Patil wrote in Dinmitra, “if you are going to avail basic human rights after converting to a new religion, you must do that.”

“For how many days will you live a life of insects and ants? If a dog enters the house of a Brahmin to eat, they are fine with that, but they find a person like you even more inferior than a dog. You must live wherever you get treated like a human being. That can be Hindu Dharma or Christian Dharma. The real enemy of Hindu Dharma is the community of Brahmin priests. It is the Brahmin community which is responsible for Hindu people converting to a new religion.” [10]

Patil carried this spirit of opposition to the received wisdom of the political elite, which was now consolidating its fight against British rule. He knew that the question of political freedom was a non-starter for Satyashodhaks, who had been able to access education only after the coming of the British. British rule, Patil believed, had brought non-Brahmins dignity and the right to choose their occupations, giving them a way out of abject servitude.

This should explain why Patil wrote in support and admiration of King George and his wife Mary, when they were received with great pomp in Bombay in 1911.

“Those who had exercised a sleight of hand before the British,” he wrote in December 1911, “they will not be happy. But those who have tasted the dignity of humanity in this rule, which was absent even in the Ramrajya: they will be extremely happy with this ceremony.”

In fact, Patil lamented, the British had arrived late. It was not merely the gifts of modernity—roadways, railways, mills and ships—which had enabled the non-Brahmin’s social mobility. He reminded his readers of the time when King George’s grandmother Victoria spent ₹22 crore from her coffers to eliminate the slave trade in 1835.

Patil’s support for the imperial rulers can be seen as a direct critique of Marathi nationalists like Tilak. It was a pushback against the idea of one nation dominated by one brotherhood. In the same vein, Patil registered his disapproval of nationalist festivals like Shiv Jayanti and Ganesh Utsav, the latter of which, thanks to Tilak, had taken a distinctly Brahmanical form of nationalism into the public sphere. “Ganpati Utsav, ban on alcohol etcetera are put forward as harmless entities,” he wrote in May 1913, “but are draped by the body-cloth of dharma under which there is a boisterous leaping and capering of political issues. Among all the other instances of pretence, who can really say this is not one of them?”

For him, these events were never meant to facilitate unfiltered discussions between Brahmins and non-Brahmins. Indeed, Patil’s challenge to Tilak and Kesari for an open discussion were repeatedly ignored. Kesari, on its part, continued to obfuscate the Brahmin and non-Brahmin division. It maligned the non-Brahmin movement as a “Brahmin haters” movement, which only represented the interests of the landed Maratha community.

Some of the movement’s prominent leaders were, indeed, Maratha. But Patil challenged this narrative in a couple of editorials, where he reminded readers of the participation of non-Maratha castes in the movement: castes that included the Mahar, Mang, Chambhar, Kumbhar, Nhavi, Parit, Sali, Koshti, Shimpi, Sonar, Lohar, Sutar, Kasar, Dhangar, Koli, Ramoshi, Bhilla, and Mali communities, as well as Jains, Lingayats and Prabhus. In an editorial published in October 1913, Patil responded to Kesari’s criticism thus: “The founder of the Satyashodhak Samaj himself was not a Maratha. The author of the book Kulkarni Lilamrut was not a Maratha. [11] And Kolhapur’s primary leader was a Prabhu, the vice-president was a Jain, and secretary a Dhangar.”

Patil never ceased to keep a watchful eye on Tilak and Kesari. One instance stands out. In 1916, Tilak made his famous proclamation, for the first time, in Ahmednagar: “Swaraj is my birth right, and I shall have it.” [12] But this was at the same meeting where he expressed disagreement with how the vatan—the hereditary estate—was taken away from the village Kulkarni.

Patil recorded this in Dinmitra, making it clear to readers that Tilak’s emotive predilections of attaining Swaraj came at the expense of his ambiguity on caste.

It was a reassertion of the right of the village upper-castes over land holding and distribution. “Vatan getting destroyed meant the seat of the Brahmin lordship becoming superfluous,” Patil had written in Kulkarni Lilamrut, four years earlier. “But in that case, who will talk about the ordinary carpenters, barbers and tailors?”

Tilak’s casteism was to be further tested. A petition formulated by Maharshi Shinde seeking the removal of untouchability was going around at that meeting in 1916. Tilak chose not to sign. Patil recorded this in Dinmitra, making it clear to readers that Tilak’s emotive predilections of attaining Swaraj came at the expense of his ambiguity on caste. After Tilak’s death in 1920, Patil continued to criticise his outsize influence, writing about how the man anointed “Lokmanya,” admired by the people, had never been never supportive of widow re-marriage, women’s education or the eradication of untouchability.

Patil’s most trenchant critique of Tilak’s nationalism came in his editorials on the Home Rule movement. Home Rule advocates should be ashamed of demanding political freedom, he wrote. In other countries with anti-colonial movements, like Ireland and South Africa, society was knit together by religious togetherness, in a faith that held all men to be equal. There was simply no rationale for demanding a nation which did not deal with the vice of untouchability. He demanded that the upper castes first grant the “smaller home rule” to non-Brahmins; and only then demand a “bigger home rule” from the British.

In its current avatar, Patil prophesied, Home Rule would only nurture the existing dominant narrative of a “Rashtra” and will not give rise to a “new Rashtra.” Strikingly, in a February 1917 editorial, Patil compared the undivided Rashtra to a gigantic tree. “I agree that Home Rule is a nutritious manure for the Rashtra tree,” he wrote, “but for that, Rashtra needs to first become a Rashtra tree.” Patil continued:

“For the birth of a Rashtra tree, it must bloom from an undivided seed. This gives birth to a Rashtra tree of one caste and then when it receives the manure of Home Rule, all the limbs (of the Rashtra) are strengthened which results in a plenitude of sweet fruits. So then, do we have this one caste Rashtra tree in Hindustan? Hindustan has many caste trees. So how will this one kind of manure be helpful for people belonging to multiple castes?”

Patil had strong words even for Annie Besant, founder of the Home Rule League. He quoted her as saying that “untouchable children must first be taught good manners so that when they come in touch with upper castes, the latter will not face any bodily harm.” In an editorial in January 1915, Patil framed a question for Besant in stark terms. “How does Besant distinguish between a Mahar and a Brahmin?” he asked. “Can she distinguish between their souls?”

inmitra shut down in 1967, the year Patil died at the age of 82. It has been reintroduced to a new generation of readers only recently. Earlier this year, Uttamrao Patil published the entire collection of his grandfather’s editorials in 10 volumes.

Mukundrao Patil was one of the few Satyashodhaks whose mission navigated both the colonial and post-colonial words, who never joined active politics, and who continued his resistance through the columns of his newspaper. He was a unique journalist who had literary flair, and a particular guile that was informed by his philosophical bent of mind.

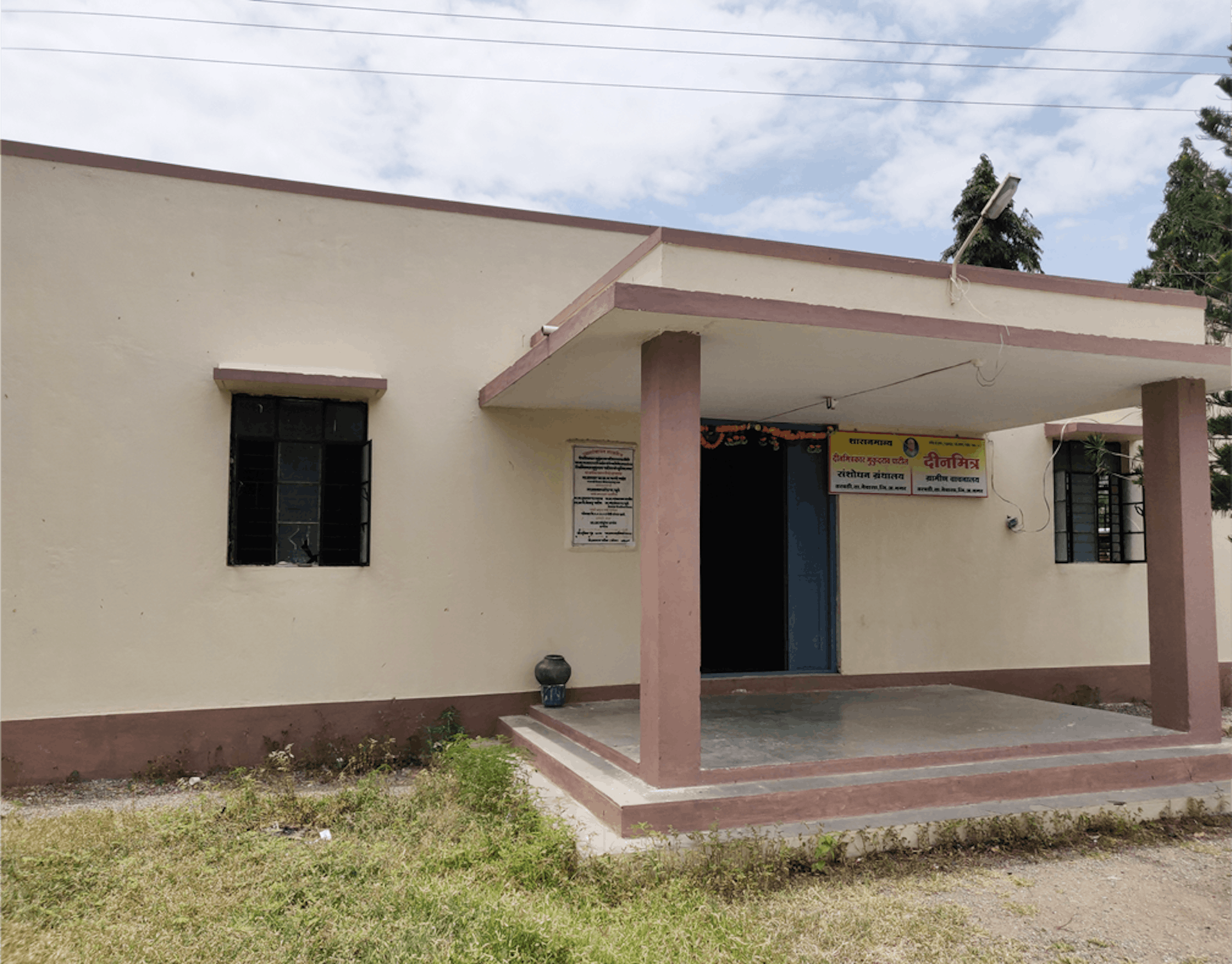

The entrance to the Deenamitrakar Mukundrao Patil Archives and Research Centre in Tarawadi. Credit: Surajkumar Thube

As the country’s political awakening intensified in the second decade of the twentieth century, we find that Patil’s own views on nation and nationalism were intimately connected to his conception of the link between the political and the social. Even before the beginning of the mass nationalism phase in India’s freedom movement, he had identified patriotism as yet another legacy of the British.

“Pride in one’s own country,” he wrote, “the downfalls of being selfish and the idea of building modern institutions like the Home Rule—we were introduced to this art of Deshbhakti by living with the British. Many might get angry with my statement and say ‘before the English, didn’t we have Deshabhimaan, Deshbhakti and Deshunnati?”—national pride, patriotism, national progress? “For them, I want to clearly say—Yes! Before the English, you did not know what it meant to take pride for your country.”

From writing like this, it is apparent that the ideas espoused by lesser-known intellectuals like Patil can offer reinterpretations of widely accepted narratives. As a majoritarian wave in India plays up the grandeur of a civilisational past, reflecting on figures like Patil can contribute to the resistance against the homogenising impulse.

Surajkumar Thube is currently pursuing his PhD in History at the University of Oxford. He is broadly working on the non-Brahmin print sphere from late nineteenth to the early twentieth century. His articles and book reviews have appeared in Scroll, The Book Review, South Asian History and Culture and Oxford Review of Books among others.