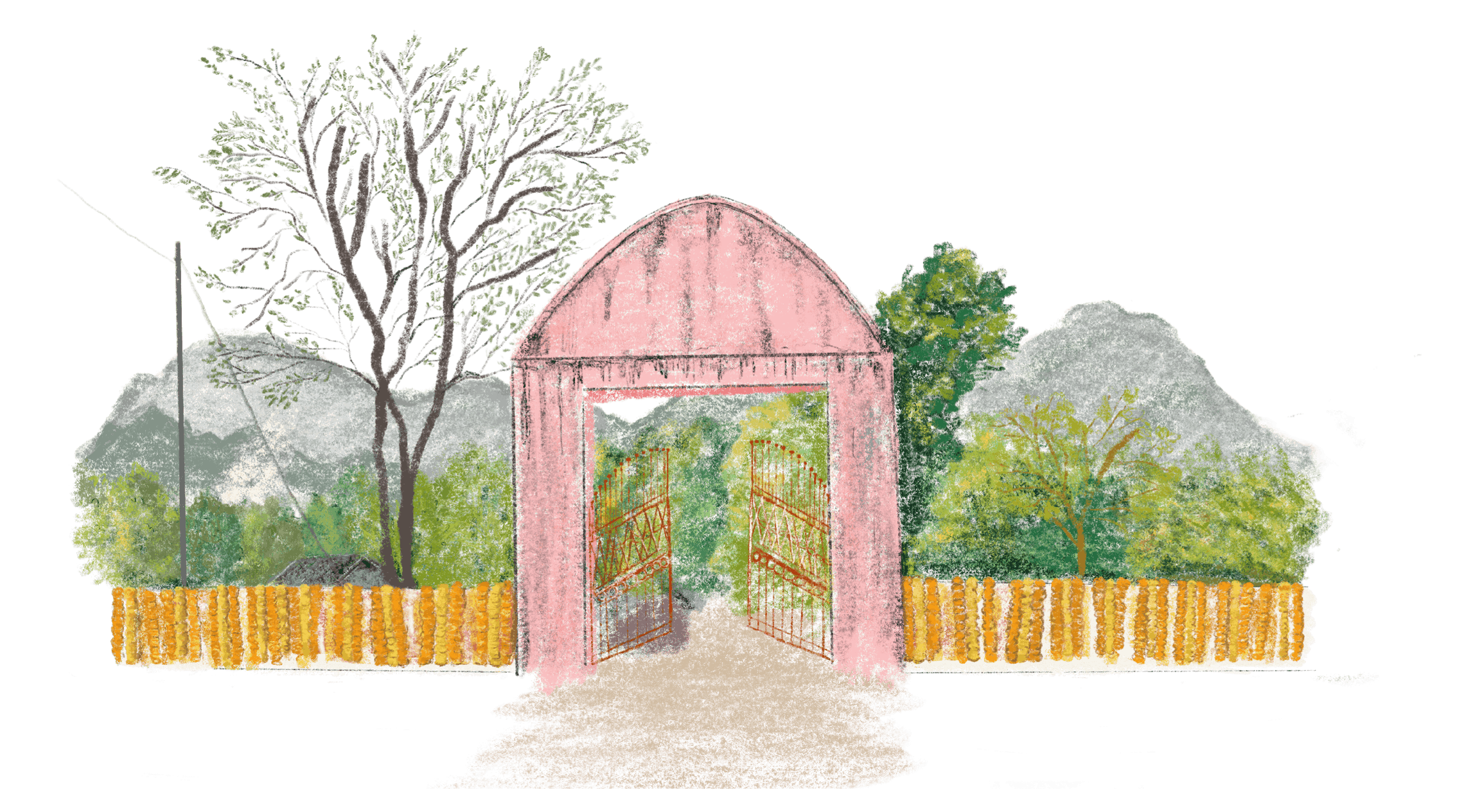

On 9 January this year, about 15 Adi women lined up outside an arch-shaped gate in Pasighat in East Siang district. Their gales, a type of wraparound skirt, were saffron with black stripes. Some 10 men were there in their galuks, red-and-black jackets, too, and they held up a banner that read: “Central Donyi Polo Yelam Kebang, Pasighat Welcome One & All ABVP Karyakartas.”

The welcoming party were adherents of Donyi Polo, which literally means ‘sun and moon.’ It is an indigenous religion followed by the Tani group of tribes in Arunachal Pradesh. [1] They’d lined up outside their place of worship, known as the gangging, which is easily identified, even at a distance, by the Donyi Polo symbol: a white flag with a red sun in the centre.

On this winter morning, the Adi group had gathered to welcome participants to a state conference of the Akhil Bharatiya Vidyarthi Parishad, the student wing of the Rashtriya Swayamsevak Sangh. That party was led by a 4x4 truck adorned with marigold flowers and mounted with pictures of Swami Vivekananda, and the Hindu goddess Saraswati.

As this contingent of roughly 500 people approached the gangging, the women in the Donyi Polo group showered handfuls of marigold flowers on the visitors. The women chorused, ‘Bomyerung Donyi Polo!’—May Almighty Donyi Polo Bless Us All! The ABVP workers chanted ‘Bharat Mata Ki Jai,’ and drowned out the Donyi Polo chants. Between the saffron flags and marigolds, it was easy to lose sight of the Donyi Polo standard.

To me, watching this from a few metres off, the scene appeared emblematic of the religious churn in public and private life in Arunachal Pradesh in the last few decades. Donyi Polo is the name given to a set of animistic practices. But a formalised form of the religion—complete with ganggings, flags and systemised rituals—only took root here from the 1980s. That was also around the time when the RSS and an affiliated organisation called the Vivekananda Kendra were gaining ground in the region.

Both movements seemed to be responding to the same phenomenon: a supposed incursion by Christians. Reclaiming indigenous identity; returning to roots: these were the themes highlighted by both followers of Donyi Polo and the messengers of the RSS. The latter view tribal faiths as part of Sanatana Dharma, a way of life originating in India and inextricably tied to Hindu practices.

Although the movement to institutionalise Donyi Polo kicked off with the aim of shoring up the religious identity of tribal communities, it has ended up blurring the lines between the indigenous faith and Hinduism. In recent years, as the Bharatiya Janata Party established political dominance throughout northeastern India, the conflation has become more intentional still. Organisations, several of whose members are associated with the RSS, are trying to leverage a practical aspect to proselytisation: you should lose your Scheduled Tribe status if you convert to Christianity, they contend; you can keep it if you’re Donyi Polo.

Crossing The Inner Line

orseshoe-shaped Arunachal, spanning snow-clad mountains in the north to the rolling Brahmaputra Valley in the south, is home to 26 major tribes and more than 100 sub-tribes. It’s a border region, and shares international boundaries with Bhutan, China and Myanmar. From colonial times until the early 1970s, it was called NEFA—the North East Frontier Agency, and was considered part of Assam.

The first people to make concerted efforts to proselytise in the region were American Baptists invited to the region by East India Company officials to “pacify” the hill tribes, who had taken to raiding the tea plantations the British had set up in the early nineteenth century. [2] The missionaries had a hard time. Nathan Brown and O.T. Cutter, for instance, had to abandon an outpost in Sadiya in 1839, following a war between the Tai Khamti tribe and the British. [3] Meanwhile, the Reverend John Firth had started a lower primary school in North Lakhimpur, on the border of present-day Assam and Arunachal, where he and his wife Eva became acquainted with the Adis, Misings and Nyishis.

Following the Revolt of 1857, tighter controls were introduced by a wary Crown after it took over from the Company. Ever paranoid about tribes they considered restive, and keen to protect the tea business, the British notified the Bengal Eastern Frontier Regulation in 1873 to control entry and exit from the hill tracts beyond Assam. This is the origin of the Inner Line Permit system, which exists in modified form to this day. Although not intended by the British, the ‘inner line’ drawn between the territory of present-day Arunachal and then Lakhimpur and Darrang districts, in present-day Assam, “proved to be a blessing in disguise in protecting the tribal rights and identity.” [4]

But the missionaries were resourceful and resolute. “They’d manage to come in even if there was an Inner Line check,” Tarh Miri, president of the Arunachal Christian Forum, told me. “They would come disguised as normal people. The Baptists came first, and they were followed by the Catholics.”

After independence, Jawaharlal Nehru’s government continued to limit the influence of external forces. His main man in this endeavour was the British-born anthropologist Verrier Elwin, who took the official position of Advisor in Tribal Affairs to the Governor of Assam. Nehru and Elwin maintained that the development of tribal communities should take place “along the lines of their own genius.” It meant an effective clampdown on Christianity: even the first Nyishi converts weren’t allowed to preach.

“The missionaries would manage to come in even if there was an Inner Line check. They would come disguised as normal people. The Baptists came first, and they were followed by the Catholics.”

In 1957, Elwin was writing about providing “a climate in which the old religion can grow.” Six years later, he was telling Political Officers that proselytisation went against the policy of “uniting our people with one another and with the rest of India.” On Hinduism, he had an interesting take, which he wrote about in A Philosophy for NEFA. He believed that the “gentle figure of the cow” stood between the people of NEFA and Hinduism even as there were other things to attract them to “that great religion”: he listed these as “the same belief in a supreme deity ruling over a host of lesser spirits, the same sacrifices, the same colourful festivals, myths and legends of rather similar patterns.”

In 1969, an apex advisory body called the Agency Council was urging the Government of India to protect the indigenous faiths of the various tribes. Three years later, NEFA was made a Union Territory and renamed Arunachal Pradesh. The Agency was replaced by a Pradesh Council which resolved that a person who has renounced the traditional faith will be deemed to have deserted the tribe, and forfeit the advantages of being a member of that community. [5]

The Crackdown

hen, in the 1970s, the persecution of Christian missionaries started in a concerted manner. K.A.A. Raja, the state’s first chief commissioner, had been sworn in as lieutenant-governor in 1975, but was “reportedly a Hindu fanatic.” [6] He called on leaders of local communities, who shared his concerns about wanting to safeguard indigenous religions. There began a slew of attacks on churches, missionaries and Christians. By 1974, 47 churches had been burnt down in one region alone. [7]

In the early 1970s, Raja invited an RSS leader and ideologue named Eknath Ranade to open schools in Arunachal. Ranade was also the founder of the Vivekananda Kendra, established in 1972 with the twin objective of “man-making and nation building.” The Kendra’s focus was on what it called service activities, like yoga, education, and natural development, meant to aid rural and tribal progress. In 1977, Arunachal became the first region to be “adopted” by the Vivekananda Kendra.

Soon, Ranade was writing to Prime Minister Morarji Desai about the threat Arunachal was facing from “separatist forces.” “Even a single wrong step in that State is likely to tilt the balance in favour of the separatist forces in that region,” he wrote. “Unless Arunachal Pradesh comes within their ambit, these forces, perhaps feel that their dreams would not be fully realised.” [8]

In 1978, the legislative assembly passed the Arunachal Pradesh Freedom of Religion Bill, which imposed limits on religious conversions. But the government’s policies were unable to hinder the spread of Christianity, which tribal people were increasingly seeking out, burdened as they were by the cost of rituals and sacrifice demanded by the indigenous faiths. [9] In the 1981 census, Christians had come to constitute 4.32 percent of the population. A decade earlier, that figure had been less than one percent.

Takeng Taggu, an Adi man, worked with the police department in the 1970s. He had actively hounded Christians but then had a change of heart. “I persecuted several Christians, burnt churches, arrested missionaries on government orders,” he told me at his home in Pasighat. In 1984, Taggu went to arrest a missionary who had come from Kohima in Nagaland. But something stirred in him when he saw, and heard, the missionary absorbed in prayer. Taggu went on to establish the Arunachal Pradesh Christian Revival Church. (He is now president of the All Adi Welfare Society.)

In 1987, Arunachal Pradesh became a full-fledged state, and some rules and unspoken conventions around conversions and evangelism were relaxed. By the 1990s, the grip had loosened further—missionaries were allowed to open schools, churches and hospitals. But this relaxation seemed to have an opposite effect on the then-fledgling cultural movement known as Donyi Polo. The ideas of Talom Rukbo, one of its main movers, hardened during this period.

Finding A Religion

orn in 1937 in the Jine area of Pasighat, Talom Rukbo became interested in promoting the language and culture of his Adi people early in life. In the 1960s, his passion became a profession when he was appointed as the Pasighat Language Officer. [10] In 1962, during the war with China, he worked for the Sashastra Seema Bal, the border forces operating on Indian boundaries with Nepal and Bhutan. He rose to the rank of Special Officer of Cultural Affairs and also served as NEFA’s Joint Director of Information.

Then, in 1972, he resigned from these positions and became an activist.

Even in public office, Rukbo had begun mobilising the Adi community. He encouraged people to celebrate their festivals and also convinced the government to notify these as holidays. He played an active role in the revival of Bogum Bokang Kebang, the highest body of Adi local governance.

In August 1968, Rukbo went to a meeting held in Aalo in the West Siang district to deliberate on a collaboration between the Adi and Galo tribes. At the meeting, people decided to build Donyipolo Dere, a community hall for Donyi Polo believers. [11] Until this time, Donyi Polo had had no such physical place of worship. The local miris—shamans believed to have supernatural powers—were called in by families to conduct home ceremonies to heal the injured or to dispel evil spirits.

Rukbo helped start several organisations, including the Donyipolo Mission in Itanagar and the Adi Literary and Cultural Society in Pasighat. He and other Adi intellectuals would often meet at the Pasighat Youth Club to discuss new ideas for Donyi Polo, including ways to codify festival dates, which varied across the Adi community.

Rukbo died in 2001. This January, I visited one of his closest associates in Pasighat, a pensive-looking man named Kaling Borang. A small bamboo structure stood in the compound of his house: it was a school where children learnt about Donyi Polo and Adi culture. On the walls of this school hung pictures of the Donyi Polo deity Doying Bote and Matmur Jamoh, an Adi man celebrated as a freedom fighter for having killed a British officer in 1911.

Borang had known Rukbo since their school days, but only grew close to him after they met through the Adi Cultural and Literary Society. In those days, Borang was working as a programme executive with All India Radio in Pasighat. In the 1970s, Rukbo’s activities were geared towards cultural revival. He wanted the Adis to develop a sense of pride in their past, so they could stay strong in the face of influences from outside the region. “To boost cultural renovation, Rukbo-ji thought of giving it a religious touch,” Borang told me.

In 1985 and 1986, Rukbo and Borang participated in conferences organised by the International Association for Religious Freedom, a UK-based charity. Members of Seng Khasi, a body of Khasi people fighting to preserve their faith in the face of Christian conversion, recommended the inclusion of the Donyipolo Mission as an associate member of the IARF. Following the second conference, Rukbo told Borang that the Adi community “must have the written scripture on Donyipolo.” [12]

An Adi religious body named the Donyi Polo Yelam Kebang was born in late December 1986. Members used to meet on Saturday nights to discuss the formalisation of the faith. They decided that Saturday would be the day for communal prayer. (The weekly day of prayer is Sunday now.) The DPYK influenced a shift in the way the animistic faith would come to be practised. Earlier, and only on ritualistic occasions, the Adis used trees and bamboo to erect an altar from imagination. [13] But Rukbo deemed that each DPYK unit have a building for their weekly prayer—the gangging.

Rukbo was of the opinion that symbols and iconography were essential to every religious movement. The DPYK started to put together a prayer book, to which painters, dancers and poets became important contributors. He invited an artist named Komeng Dai to a conference for the recitation of abangs, mythological oral narratives, and asked him to illustrate what he heard. Dai painted scenes from the prayers and also came up with depictions of three Donyi Polo deities: Kine Nane, the deity of grains; Doying Bote, the god of humans and wisdom; and Dadi Bote; the god of animals. This was the first time the deities had been represented in human form.

The images were later mass produced, and Dai’s representations are common and widespread today. At the altar of the Central Donyi-Polo Yelam Kebang gangging in Pasighat, statues of Kine Nane and Doying Bote flank the pictorial depiction of the supreme power Donyipolo, represented by ray-emitting concentric circles. Doying Bote carries a spear and wears traditional Adi headgear, with a string of beads. A squirrel, a recurring presence in the myths, rests on his shoulder. Kine Nane wears a gale and holds paddy in her hand.

It seems that Rukbo was influenced by both Hinduism and Christianity as he went about institutionalising Donyi Polo. But the scholar Pralay Kanungo has argued that Rukbo was more interested in the parallels, if not overlaps, with Hinduism. Rukbo often stressed on the faith’s similarities with Hinduism: the Adi concept of keyum—primordial nothingness—was like the Hindu Aum; the abangs found a parallel in the shastras; both faiths centred on the worship of numerous gods and goddesses and a supreme, omnipresent, omnipotent power—Bhagwan in Hinduism and Donyipolo in the Adi faith.

Borang, however, was clear that no new practices were introduced in this formalised version of the Donyi Polo faith. “They were traditional practices that we adopted to suit our present-day necessities,” he told me emphatically.

The Saffron Connection

Our brethren in the far Eastern region—they may be Naga, Khasi, Jayantia, Mikir, Mizo, etc.—all should designate their community as Hindu only, whatever the differences in their ways of dress, languages, food and local customs. The basic truth about our single social entity should always be borne in mind.” So wrote M.S. Golwalkar, one of the most prominent ideologues of the RSS and a proponent of the concept of the Indian cultural nation, the Hindu Rashtra.

The RSS’ presence in Arunachal Pradesh has made mainstream news only in recent years, but the organisation has been active here for more than three decades now. Talem Mize, an RSS karyakarta, remembered the first time a pracharak came to his village of Rayang, located in the Ruksin circle of East Siang in the 1990s. He was a man named Chandrashekhar Deshpande.

“Chandrashekhar-ji told us that we should work for society,” Mize, who also goes by the name Dheeraj, told me in his single-room house in Pasighat. “He said, there are many who are impoverished. So we should fix society, we should come to the Sangh and be associated with the Sangh.” It fired Mize up. He became increasingly engaged with the organisation before joining it formally in 2000. His initiation happened during a ceremony commemorating RSS founder K.B. Hedgewar’s birth anniversary.

As a karyakarta, Mize’s job was to “spread awareness” in villages as part of a drive the RSS called ‘jan jagran abhiyan.’ He went and spoke to people across the state about preserving what is theirs in the face of the Christian influence. “By just changing our bhesh bhusha”—outward appearance—“we can’t become something we are not. Even if my mother is poor, she will still be my mother,” he said.

“We didn’t have experience and the RSS helped us in a lot of aspects like seminar work, personality development training.”

The RSS runs jan jagran programmes in many of India’s tribal areas under the aegis of the Vanvasi Kalyan Ashram, which is called the Arunachal Vikas Parishad in this state. Established in 1993, the AVP’s founding president was Talom Rukbo. Borang told me that Rukbo was close to many RSS pracharaks. “We didn’t have experience,” said Borang, “and they helped us in a lot of aspects like seminar work, personality development training.” Rukbo travelled regularly with Dwarka Acharya, the organising secretary of the VKA who had come to Arunachal in the late 1980s.

Back in the 1990s, there were already objections that Rukbo’s version of Donyi Polo was Hinduised. Borang told me it was a topic of discussion between the two men. “I had advised him to not meet with the Sangh a lot, because at the time people were saying that we were trying to make the society Hindu,” Borang said. “But Rukbo-ji’s point of view was that the RSS, being a big organisation, had resources to help him travel.”

The RSS openly applauded Rukbo’s efforts. In 1996, an RSS-affiliated organisation called the Bhaorao Deoras Seva Nyas organised a function to honour Rukbo. There, he was introduced as ‘Dharmik Sant aur Sahitya Manishi Shri Talom Rukbo’, the Religious Saint and Learned Litterateur Mr. Talom Rukbo. The citation in the congratulatory note for Rukbo read: “Under your guidance many religious, social and national projects to build the new India have been undertaken.”

Even now, the fact, and extent, of the RSS’ influence on Donyi Polo is a touchy topic. Tajom Tasong, secretary general of the Central Donyi-Polo Yelam Kebang and national executive member of the VKA, unequivocally agreed that RSS has contributed to Donyi Polo. But a senior RSS functionary in the state, who spoke to me on condition of anonymity, said that it was wrong to suggest that the RSS was trying to Hinduise the indigenous faith. “The Yelam Kebang is totally different,” he said, “and the Sangh maintains an association with everyone, and tries to advertise their qualities.”

Borang believed that while there was initially confusion about the “Hindu influences” in the formalised version of Donyi Polo, people had come to accept it. “They realised it is truly needed,” he told me. The proof is in the pudding. Over the years, Tajom Tasong told me, over 40 ganggings have sprung up in the East Siang district alone. Its influence has been such that even other Tani tribes, like the Nyishi, have followed suit.

Bamboo Dreams

met Mekory Dodum in her office, located in the building adjacent to the Deputy Commissioner’s office in Seppa in East Kameng district, about 426 kilometres from Pasighat. Mekory, who is 29 years old, was appointed as the Trade Development Officer of the district in 2020. “I am a researcher too,” she told me, pushing up her dark glasses. Mekory is currently pursuing her PhD from the Department of Sociology at Tezpur University. Her thesis is on the social change taking place within the Nyishi community of East Kameng. “So far,” she said, “I found the change to be only about religion.”

Mekory described herself as “an insider who is also not an insider.” From kindergarten to Class 2, she attended the St. Joseph’s School in Seppa. Soon after, she was packed off to the Vivekananda Kendra Vidyalaya, Nivedita Vihar, a girl’s residential school run by the Vivekananda Kendra Vidyalaya Arunachal Pradesh Trust, in Seijosa, East Kameng, where she studied till Class 10. (Since 1977, the VKVAPT has established 41 schools across 15 districts.)

Meanwhile, a major churn was taking place within the Nyishi community. Taking a leaf out of the Adi book, several prominent members of the tribe held a meeting in Doimukh, close to Itanagar, in January 2001. The meeting led to the establishment of the nyedar namlo—the Nyishi equivalent of ganggings.

Back in Seppa, Mekory’s father P.G. Dodum and several others started the District Nyedar Namlo Committee. P.G. had been a karyakarta of the Vivekananda Kendra for 35 years, and RSS and VKV karyakartas regularly stopped over at the Dodum house. In the early years, members of the committee travelled to far flung places to meet nyubus—traditional priests—and document prayers and rituals which had only been passed down orally. This exercise culminated in the production of the Nyetam, the “holy book” of the nyedar namlo.

Traditionally, nyubus performed rituals or prayers only during specific occasions, such as funerals or to heal the sick. The ceremonies could take up to 10 days and would involve the sacrifice of chickens and mithun, a gaur-like domestic cattle, to appease the spirits. “Ours is a need-based religion,” Mekory told me. “In this process of institutionalisation, they adopted many things from other cultures, major religions that are already formalised.”

I remembered Mekory’s words at the prayer gathering I attended at the nyedar namlo at Seppa. Men and women sat separately, facing the altar in a large hall. Decorations of bamboo called karchi karlo hung from the ceiling. In the centre, ensconced in a glass case, reposed a marble statue of Anye Donyi, the sun goddess. She wore a gale and a multicoloured beaded necklace.

A brass lamp, typically seen in Hindu pujas, flowers and several agarbattis were placed in front of the glass case. Two nyubus, donning the traditional Nyishi headgear called byopa, sat at the altar. The gathering then sang prayer songs. An hour later, the nyubus went around the room sprinkling the faithful with water from ginger leaves. This was described to me as “a purification ritual.” The gathering dispersed after repeated chants of “Aaturtoh anye donyi, Aaturtoh anye donyi,” long live Anye Donyi. On the ground floor, people had queued up to receive ataang, a mixture of rice powder and ginger.

“We follow the Sanatana Dharma in the way we do puja path,” Karling Dolo, then chairman of the District Nyedar Namlo Committee, explained. “There is a 90 percent similarity with Hindus. We would use charcoal, which has now been replaced with agarbattis.”

Changes like this one had emerged as points of conflict between father and daughter in the Dodum household. “RSS, ABVP and VKV have given moral and monetary support to this movement,” Mekory said. “So I feel like this is a trade. I question my father, I ask him ‘Don’t you think there has been too much influence in Donyi Polo?’”

A few days before my meeting with Mekory, Birendra Dubey, zonal organising secretary of the VKA, had told me that the organisation only asks for donations to facilitate the construction of structures like the ganggings. “We don’t directly work for Donyi Polo, but help in bringing awareness among people about how to establish their identity, their language,” he said.

P.G. Dodum defended the changes in the practice, contending that they had prevented more conversions from taking place. “Yes, there are a lot of similarities with Hindus,” he said. “We are nature worshippers. In Hinduism, there are five elements—fire, earth, water, sky, air. Without these, we won’t survive. So that is a replica of Sanatana Dharma. But it is still a different language in comparison to Hinduism.”

Even at the community level, the transition hasn’t been easy. Conflicts emerged over the depiction of Anye Donyi, who was otherwise considered to be formless. The statue at the namlo in Seppa, conceptualised by Nyishi leader Techi Gubin—who is also AVP’s current president—is the only one that exists. “This was mistakenly done under the leadership of Pai Dawe and has created a lot of issues,” Robin Hissang told me. “We consider Anye Donyi as omnipresent and formless.”

Hissang, principal of the Government College of Seppa, has been on the frontline of the revivalist movement within the Nyishi community. But he’s concerned by the portrayal of the movement as coming “under the fold of Hinduism.” “They say we are Hindu, but this is a design of external forces,” he told me. “This is a crucial and serious matter. We can’t lose our identity.”

Pai Dawe, the leader Hissang referred to, is a wearer of many hats: president of the Nyishi Indigenous Faith and Cultural Society, ex-officio member of the Indigenous Faith and Cultural Society of Arunachal Pradesh, vice-chairman of the Donyi Polo Cultural and Charitable Trust. Unsurprisingly, he also served as the district president of the AVP. “There are certain differences, but we have been inclined to Sanatana Dharma philosophies as there are similarities,” he told me. “Hindu is part of our tribal belief.”

Another bone of contention within the community has been the training programme for nyubus run by the District Nyedar Namlo Committee. In the traditional way of life, you can’t appoint a nyubu, Topo Yangda told me. All naturally ordained nyubus are chosen based on a dream in which they see themselves going up a mountain and spotting a particular bamboo structure. Yangda, 61 years old now, saw the dream when he was a child. “Nyubu is usually a blood relation,” Yangda said. “If you are a nyubu, then there are others in the family who will also be a nyubu.”

When the training programme was instituted, a section of nyubus went up in arms, claiming that real nyubus are bestowed with supernatural powers and “can’t be trained.” But Hissang argued that the training programme is necessary. “We are training the nyubus in whatever the original nyubus have been saying,” he said. “We are only documenting and imparting this to the younger generation because the institution of nyubus is dying.” Gradually, he said, the older nyubus have accepted this and started participating in the namlo’s activities. “We are working together,” Yangda said. “They are like constables and we are like superintendents.”

As we sipped tea in her office, Mekory pointed out that the transformations within the community are rooted in the contestation between converted Christians and the Donyi Polo believers. She’s all too familiar with this crisis of religious identity, given her own schooling. As a Class 2 student, Mekory would often feel excluded when only baptised students were given the sacramental bread after Sunday mass. A year later, after joining the Kendra school, she found herself reciting Hindu prayers—like those from the Bhagavad Gita—six times a day.

“If I had stayed for a few more years in the convent, perhaps I would have told my parents that we should convert to Christianity,” she said. “But maybe because I went to VKV, I am more comfortable visiting temples.”

The Tug-of-War

he road to Chayangtajo from Seppa is a long, arduous one. The terrain it traverses is marked by big hills and deep valleys. The sparsely populated town has historically served as a security outpost for the state since the time it was NEFA. The international border with China is just 50 kilometres away. The snow-capped Chiumo peak, located at the border, emerges from the clouds at dawn.

According to the 2011 census, 37.41 percent of the 6,937 people living in Chayangtajo are Christian. The church here was built nearly 40 years ago. Nani Bath, a professor of political science at the Doimukh-based Rajiv Gandhi University, told me that the church has been “much more aggressive than the RSS” in Arunachal Pradesh. In remote areas like Chayangtajo, more people are likely to convert to get better access to education and medical facilities. Some convert for “miracles.”

“We did the Donyi Polo rituals. We sacrificed mithun. We had given the nyubu a lot of money. Even then, nothing happened. But it was only after I converted to Christianity that one of my children survived.”

Yago Tango, a 50-year-old shopkeeper in Chayangtajo, turned to Christianity in 1986. She was looking for a miracle. “All my children save one had died from illnesses,” she told me. “We did the Donyi Polo rituals. We sacrificed mithun. We had given the nyubu a lot of money. Even then, nothing happened. But it was only after I converted to Christianity that one of my children survived.”

Chayangtajo has a nyedar namlo, too, right in the centre of town. It was inaugurated in 2005, four years after that meeting in Doimukh. Its gate is decorated with the customary bamboo and flags. Here, I found Tame Yangfo. The 68-year-old has been a regular worshipper at the namlo ever since it opened. Originally from the nearby village of Keyong, he migrated to Chayangtajo in the mid-1980s, “when Arunachal was still a union territory.” “We were all engaged in agriculture then,” he said. “There were only bamboo structures here. At that time, even if people had a bad dream they would call the nyubu.”

Tame Yangfo claimed to have never swayed from Donyi Polo despite several people asking him to convert. “When the namlo came, we thought it was good,” he said. “But we didn’t know the prayers, because we would conduct the rituals in our homes before.” The opening of the namlo caused Sama Yangfo, the 60-year-old caretaker of the place, to come back to the fold. “We had converted to Christianity when my child fell sick,” he said. “But four of my children ended up dying.” Since the namlo has opened in Chayangtajo, he said that no one has fallen sick in his family.

In 2015, there was a spate of “reconversions” through rituals known as Agu Vvkar, which literally translates to “a return home.” Families who want to return to the Donyi Polo fold undergo darkhya or repurification, involving the chanting of hymns to call back the spirits of the elders who had strayed. P.G. Dodum described this to me as ‘ghar wapsi,’ a phrase popularised by right-wing organisations to refer to the programme by which Indians of other religions formally revert to their ancestral Hindu faith. In 2022, Dodum claimed, about 165 families in Seppa had reconverted.

n July 2020, a viral video showed a group of people burning a Donyi Polo altar during the conversion of a family to Christianity. On the occasion of Indigenous Faith Day in December 2021, photos of people with placards demanding the withdrawal of Scheduled Tribe status of Christian converts made the rounds on social media. They’re part of an ongoing uptick in hostilities between Christians and followers of Donyi Polo.

The Indigenous Faith and Cultural Society of Arunachal Pradesh, several of whose members are also engaged with the RSS and affiliated organisations, has been demanding that the government delist converts and implement the provisions of the 1978 Freedom of Religion Act, for which the state government has not yet framed rules. “These hostilities inside a community will only grow,” Nani Bath, the professor, told me. “It is difficult to understand what we are protecting now, whether we are fighting for religious identity or indigeneity. And then, there comes the politics.”

On my travels in January, I visited a school called Nyubu Nyvgam Yerko (NNY) in Rang village, located on a hill overlooking Seppa. The institution, modelled after a gurukul, was opened by the Donyi Polo Cultural and Charitable Trust in 2021 and is run in collaboration with the VKV. Subjects include the Nyishi language, English, mathematics, environmental science and social science. Every other Wednesday, students recite verses from the Bhagavad Gita. On the Wednesday I visited, boys in striped black-and-white vests—typically worn by Nyishi men—recited in unison:

Na karmaṇām anārambhān naiṣhkarmyaṁ puruṣho ’śhnute

Na cha sannyasanād eva siddhiṁ samadhigachchhati

One cannot achieve freedom from karmic reactions by merely abstaining from work,

Nor can one attain perfection of knowledge by mere physical renunciation.

Angana Chakrabarti is a Guwahati-based independent journalist. She writes on politics, policy, human rights, security, and the environment. She tweets @AnganaCk.