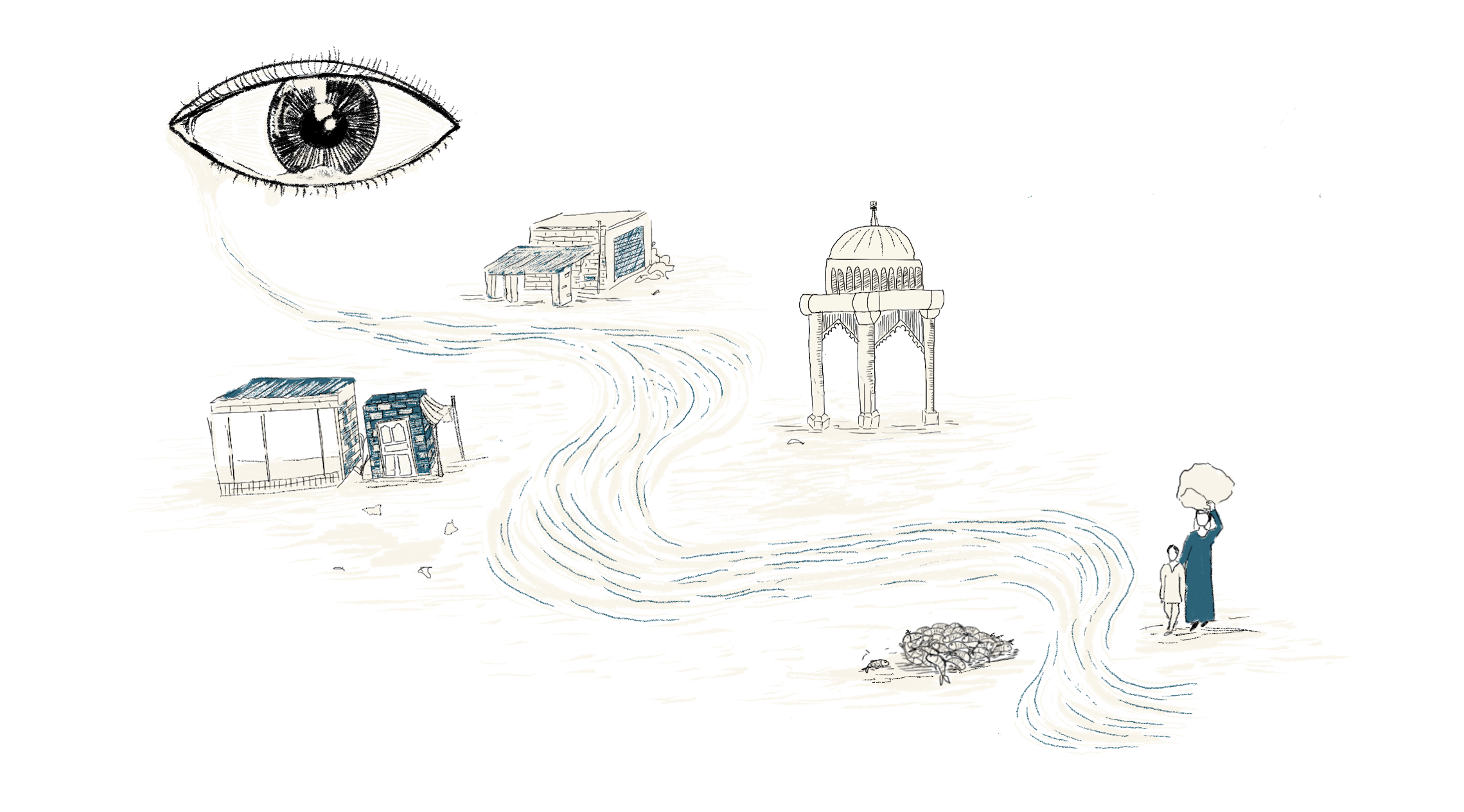

On 12 November last year, I was standing on Sujawal Bridge near Thatta, at the point where the Indus flows into its delta. It looked like the river was dying. During most months, there is sand in her mouth and the Arabian Sea keeps encroaching on her. Her tides dance only during the floods, but what a deadly dance it is. In this melancholy state, I set out in search of the old rivers: Hakra, a one-time tributary of the Sutlej, and Puran, a tributary abandoned by the Indus.

Already in September I had witnessed the carnage caused by the floods that ravaged Pakistan from June. In Mirpur Khas, Badin and Tharparkar in lower Sindh, I saw thousands of helpless, hapless people, stranded on roads and on the sides of breached embankments. There was water everywhere. The worst thing I saw was a funeral for a child, where the women mourned in a way I can’t explain.

Now a couple of months had passed, and the roads were littered with the signs of those temporary refugees. The shattered people who had gathered here when the floods raged had returned to their villages, leaving behind the breakers that once alerted speeding cars and trucks to their presence.

Tara Chand’s Sorrow

was on my motorbike. After wandering like the mad Puran in search of its waterways, I reached an otaq—a meeting place—in Jan Mohammad Laghari village, near Jhuddo, about 160km from the Kotri Barrage. It was a cold night, made heavier by the passing of northern winds. In the air, there was the smell of something dead.

That night, I lay on a Sindhi cot and spoke with 25-year-old Tara Chand. My interviewee was young and handsome, with a face that seemed painted over by agony. The colours of that agony were colonialism, caste and class. In 2021, he lost his two-year-old son Mahaveer. “I’d gone to work and our women were busy making makeshift plastic sheets, so no one could see him,” Tara Chand said. Mahaveer drowned in a ditch that was filled with flood water.

Memories of that fateful night had come back during the 2022 floods. The Puran had breached an agricultural bund and rushed towards Tara Chand’s home. Six members of his family were inside—his parents, his wife and his three children. “I could see the same waters which had killed my son coming for the rest of my family,” Tara Chand said. Somehow, all of them survived. “I carried my two daughters in my arms,” he said. “I wept a lot that night.”

After he told me this, Tara Chand became as silent as the dead river Hakra. A song by the popular Sindhi singer, Fozia Soomro played softly on his mobile phone.

Kean hath hilya ta gorha garhi paya,

Awheen yaad aya ta gorha garhi paya

When someone waved, tears rolled down,

When I missed you, tears rolled down

But music cannot heal wounds. It can only numb them for a moment. Tara Chand’s trauma is endless and experienced many times over: it’s the trauma of a downtrodden Sindhi farmer; a marginalised Hindu; an alienated Kohli.

Next morning, as the sun rose over the dusty landscape, I bid him farewell. He had to go work on the lands, and I had to keep moving. I promised to come back and meet him at the end of my travels. Hearing the sound of my phatphati motorbike, seeing the road stretching out, I felt a sense of contentment about my nomadic lifestyle.

In parting, I echoed his farewell, one that evokes a sense of camaraderie: ‘yaaro yaari.’ Over this journey, I would meet many more like him—people who’d lost everything to the water, but had always known it better than all others.

The Hakra and The Puran

he Hakra and Puran rivers were once the lifelines of the villages I was travelling through: they had kept these hamlets and communities going through the toughest of times. The Hakra, a non-perennial river often equated to the mythical Saraswati of the Rig Veda, is thought to have sustained the Harappan civilisation. The Puran was once the lifeblood of the local economy in lower Sindh, enabling agriculture and fuelling the growth of towns and cities.

Colonial infrastructure projects had a lot to do with upsetting Sindh’s delicate balance between river and sea. Before the British arrived, the landscape was largely populated by agro-pastoralists whose movements synced with the fluctuations of the Indus’ river basin. The canal systems built by the British—mainly for year-round irrigation and extending the reach of the rivers—had far-reaching consequences on ecology and hydrology. The construction of barrages and the introduction of intensive agriculture practices contributed to the rivers’ decline. The Sukkur Barrage, built in 1932 to regulate water flow from the Indus into the Hakra, significantly altered natural flow patterns.

The system of land ownership and water management favoured large landowners and British interests. The histories, rights and knowledge of local communities were disregarded, leading to displacement and resource conflicts that continue to this day. Today, the Hakra and Puran run mostly dry, with only occasional flows during monsoon season. The communities that once depended on them for their livelihoods have had to adapt to new ways of life.

A Great Calamity

Separation is a death knell—whether it be between two lovers or two rivers,” said Zahid Kumbhar, a tall poet who’d composed a book on the history and geography of the Puran. We were talking about the Left Bank Outfall Drain project. This is a drain built in Sindh province between 1987 and 1997, using funding from the World Bank and the Asian Development Bank. Its purpose is to collect saline water, floodwater and industrial effluents from the land located in the river basin of the Puran.

“But the monstrous LBOD has inflicted five wounds upon the Puran,” Kumbhar lamented, referring to the five points along the course of the old Puran where the canal has been cut. “It is as if the very veins of a living being were severed: from feet to legs, wrists to hands, chest to heart.”

The LBOD system comprises a spinal drain, main drain and sub-drains that run through the districts of Shaheed Benazirabad, Sanghar, Mirpur Khas, and Badin. The spinal drain splits into the eastern Dhoro Puran Outfall Drain (DPOD) and the western Kadhan Pateji Outfall Drain (KDOP), which discharge into the Arabian Sea and Shakoor Lake, respectively.

Despite being designed to discharge a maximum of 4,500 cusecs of water, with 2000 cusecs draining through the DPOD and 2,500 cusecs through the KPOD, heavy rainfall often overwhelms the system and causes breaches. In 2022, it is estimated 10.7 lakh people were displaced and around 5 lakh acres of agricultural land was affected in the areas of Badin, Umerkot, Mirpur Khas and Tharparkar.

In 2004, an Inspection Panel appointed by the World Bank acknowledged that the LBOD had serious flaws in planning, design, execution and supervision.

Land routes and irrigation projects connected with the LBOD have also obstructed the natural waterways of the Puran and Hakra. Shahid Khaskheli, a journalist, told me that the closure of two natural waterways is clearly seen near a spot called RD-29, where the Mirpur Khas Main Drain is discharged. Instead of restoring the flow pattern of the Puran, the water is directed to the spinal drain near the village of Kot Mir Jan Mohammad. When the width of the natural waterway and the spinal drain is compared, Khaskheli said, it appears that a large volume of water is being pushed through a narrow channel.

Allah Bachayo, a writer and journalist from Badin, has been working to restore natural waterways and resist harmful development projects in the region. In 2015, he published a Sindhi-language book on the poor design of the LBOD and the devastation it caused. Its title is LBOD, Hik Maha Afa’t. It translates to LBOD, A Great Calamity.

When I met Allah Bachayo in Kadhan, he told me about the 2003 floods, when he saw the dead bodies of humans, livestock and wildlife floating in the floodwaters. Eleven members of the same family, most of them women, had died then, he told me.

The Fear of Sawan

s the sun travels through Cancer and marks the arrival of sawan, the earth transforms into a lush and verdant landscape. It is the monsoon season, cherished and romanticised in folk songs and poetry. Three centuries ago, Sindh’s beloved poet Shah Latif sang of the rain as a mercy and a blessing.

But, now, the rains that once brought prosperity cast a pall of fear and mourning. The rivers, once free-flowing and mighty, stand blocked and uncertain of their path. There have been four major floods in the last two decades, after the construction of the LBOD. Badin flooded in 2003. Almost the whole of lower Sindh sank in 2011. The 2020 flood situation was exacerbated by the pandemic; and then, we all know about the devastation of 2022.

I was thinking about these floods when I reached the village Muhammad Umer Dalwani of taluka Tando Bago. That’s where I met Ali Nawaz Dalwani, a 50-something man wearing a rich, dark moustache and a Sindhi topi. I felt he resembled the famous singer Jalal Chandio.

The kind of havoc that the flood waters had wreaked in the last couple of decades was unprecedented, he told me. “If the Puran always flooded like this, cities like Jhuddo, Digri, Mirpur and Tando Jan Muhammad could never have been built on its banks,” he told me. “The rivers provided safety to people and their livestock. You’re going to lose if you challenge the laws of nature. These people have challenged nature.”

Ali Nawaz was unwavering in his passion and his candour. “The Kadhan Pateji Outfall Drain was moved towards the west,” he explained. “We know water doesn’t move towards the west; it moves from north to south. That is why we are flooded.”

Before the diversion created by the LBOD, he said, the Hakra and Puran used to meet at a spot called Jaar jo Patan. After travelling through various places, they flowed into Shakoor Lake and finally drained into the Arabian Sea. “But now, the Hakra and Puran can’t meet each other as easily as their paths are blocked at different places,” Ali Nawaz said. “But they do meet eventually, and that’s only after destroying everything because they don’t like their way being blocked.” At a place called Zero Point in Badin, the natural path of the Hakra river is completely blocked by a barrage.

Since 2010, Ali Nawaz has been committed to the cause of restoring the old waterways. He’s been advocating for a cut close to where the Zero Point barrage stands, so that the Hakra can return to its natural course. Last year, in the wake of the floods, he played a key role in mobilising protests. “We gathered at Thar Coal Road,” he recalled. “Our voices united in a call for justice, and thousands joined our protest. People from the areas of Pangrio, Jhuddo, Tando Jan Muhammad joined us. The protestors included the old, the young, women and children.”

A rival group launched a counter-protest: they were not in favour of the drain cut at Reduced Distance 211 in Badin. The pro-cut group staged a sit-in at Shadi Large, while the anti-cut group staged a sit-in at Navy Chuck. A girl died on the fifth day of the protest. Her relatives blamed the pro-cut group, claiming that their protest had prevented the girl from reaching the hospital on time.

Ali Nawaz’s pro-cut group was not spared in the violence that ensued. His band of protestors were beaten and humiliated by an angry mob. An FIR was filed against him and 30 others after their vehicles—including tractors and motorbikes—were seized. But Ali Nawaz’s spirit has remained unbroken despite the ordeal. His connection to the land and to the grievances of his people ran too deep, it seemed to me.

The Smell of Dead Fish

here have been others like Ali Nawaz, people who protested despite the odds and adversity. Over the years, they’ve gone on hunger strikes and demanded inspections of various aspects of the LBOD project.

In 2005, a seminar was held by social activist Mustafa Talpur where well-known people like M.H. Panhwar and Allah Bachayo Jamali had spoken about the devastation caused by the LBOD. In 2007, an Awami Adalat—People’s Court—was held in Roopa Mari, Badin. Over 2,000 men and women from the project-affected area came together to seek redress for the environmental degradation, displacement, and economic losses caused by the project.

The organisers collected over 7,000 signatures and sent a letter to the World Bank, the ADB, and other stakeholders. Their demands were clear: compensation for losses, writing off of the entire LBOD loan, and the closure of the spinal drain until upstream effluents could be properly disposed of. But it came to nothing: their proposed management action plan was rejected as being too vague, and top-ups to the loan continued to be granted.

When I resumed my journey, I crossed the Naukot market, which I was told had been constructed over the Hakra. In Tando Jan Mohammad, I could see the floodwaters spread over many kilometres on the sides of the road. Nearly three months had passed since the last torrential downpour of the year, but the water was still there. Floods are not new to Sindh, of course, but the difference is that earlier, it would only take days for the water to drain into the Arabian Sea.

In a public park near the press club of Tando Jan Muhammad, I met Zahid Kumbhar, the poet and orator who had composed a book on the Puran. I was shocked to learn that he didn’t know how to read and write. He used to sell masala puris on his bike, and had travelled along the banks of the Puran, all the way to Shakoor Lake. Friends and family members were his amanuenses, and they wrote down his observations about the river. He didn’t have any money even after publishing the book—especially after publishing the book—so his friends helped him get by.

That day, he quoted from the eighteenth-century poet Shah Latif’s Sur-Dahar. The poet asks a thorn about the Puran and a merciful king called Jashodan, who is believed to have distributed all his wealth among a drought-stricken populace:

Tell me, Kando, some anecdotes of the lord of the river,

How were the nights, how were the days then?

Tell me, Kando, some anecdotes of the lord of the river,

Your condition shows that you are passing hard days,

Kando, is it true that the dear ones have abandoned you?

It is strange that your fruit is so full, that it drops in

bunches despite your bereavement,

What was your age, Kando, when the river flowed full?

Did you meet any messenger like Jasodan?

Then, Kumbhar told me what had changed in his own time. “If you go down from Mirpur Khas till the Rann of Kutch, you will see different lakes. There were lots of fish in these lakes and people were happy. Have you heard the Sindhi proverb ‘Macchi mani je laiq’? It’s used to refer to a person rich enough to provide his family with fish to eat. It comes from this region.”

Now, these areas are haunted by the absence of life-giving rivers. Tharparkar, the Rann—they lie dry and barren for most of the year, their parched earth cracked and brittle under the unforgiving sun. Flood water, if allowed to travel on natural waterways, could breathe new life into this arid landscape.

We were silent for a while. I recognised the stale smell of death that had hung over the air in Jan Mohammad Laghari, Tara Chand’s village. It was the dead fish, Kumbhar told me. The toxic effluents from the Mirpur Khas Main Drain and the spinal drain had spilled over during the floods. “The fish died of toxic water during the flood,” Kumbhar said, “and the smell is everywhere.”

The Ghazals of Khoso

spent that night in Jhuddo city. The dim light of a bulb cast a haunting glow on the water-stained walls of the room. My mind was transported to the submerged village of Hayat Khan Khaskheli, where the rising tide had left families struggling for survival. The home of one boatman, who rescued many others, was inundated with water. His family members, who lived 300km away from him near the Keenjhar lake, had also been displaced due to floods.

Meanwhile, divers constructed a makeshift barrier of bamboo on the wet bed of the Puran, where the breach had occurred, in an effort to stem the flow of water. I saw families running behind trucks and cars, holding utensils in their hands. It was humbling and insulting to see human beings reduced to such desperate measures, but hunger knows no shame.

I reached Raees Ahmed Khan village to meet another poet, another protestor. Ayoub Khoso, a renowned figure in Sindh, has written 17 books of poetry and prose. The prose book is a jail diary titled Deewaran Ji Dunya Poyan—Behind the World of Walls. Following the floods last year, after his social media posts about his plight went viral, he was offered PKR 50,000 by the Sindh Cultural Department. But he turned it down, asking the government to restore the natural waterways if they truly wanted to help his people, many of whom were displaced.

In 2011, the floods had caused him to migrate to Tharparkar from Jhuddo. A journey that would have taken two to three hours on a routine day took him 22 hours to complete. Last year, during the floods, he was taking refuge in a half-constructed shelter in Jhuddo city, when he lived through a night he described as doomsday.

“Around 11 o’clock one night, the clouds gathered and it started raining heavily,” he said. “People didn’t have tents, they only had plastic sheets. Some didn’t even have that. I spent all night listening to the unbearable screaming and cries of children. Their mothers tried to seek shelter under shop windows.”

He recited a verse from one of his ghazals:

The shaded resting places of our hearts, drowned

The whole of new-born dreams, drowned

The jasmines lying at the doors, dried

The reddened pitchers of roses, drowned

The Puran’s width used to be more than 250 feet when it crossed between Jhuddo city and Badin, Khoso told me. He was talking about “just five-six decades ago.” “Now, it is 35 feet. Jhuddo city expanded and encroached on the bed of the Puran with time. Where the Puran once flowed, there are building and markets.”

Khoso’s complaint was that governments have always lavished special attention to the cities, while dismissing the problems of the villages and the countryside. “Look at the destruction of Karoonjhar,” he said, referring to the mountain range on the southeastern edge of the Tharparkar district, where historical sites are threatened by indiscriminate granite mining. “Our mountains, rivers and deserts are different from the other natural places of Pakistan.”

On the night he described as doomsday, he kept walking towards his village from Jhuddo city. “I was not in my senses,” Khoso said, “The flood water was touching my shoulder but I kept going. The city was haunting me.”

More lines from Khoso the poet:

Ahsas dukhyal ahin, zakhman san rangyal ayoon,

Sadman ji silaban tey her waqt tangyal ayoon

Feelings simmer, we are coloured with wounds,

We are hanged at the cross of traumas

Khoso recalled that his participation in the resistance for the opening of the natural waterways began in “2010 or 2011.” But, back then, despite the suffering and destruction, the courts had turned a blind eye. By the end of 2011, the protests had petered out.

After the 2022 floods, there was a fresh spate of protests. But even these were met with official indifference, at best, and legal charges, at worst. Yet, Khoso said, the resistance continued with the support of groups like Awami Tahreek and Jeay Sindh Qaumi Mahaz. “The resistance is not a matter of politics but one of survival,” he said.

Khanzadi’s Crusade

n the remote village of Fazal Muhammad Kapri, close to Jhuddo city, I met an organiser in her late twenties. Khanzadi Kapri is an outlier in more ways than one: her fight is not just against the authorities who have blocked up the natural waterways, but also against a patriarchal society that seeks to keep women oppressed and uneducated.

Despite severe opposition from his community, Khanzadi’s father, a progressive teacher, poet and member of Awami Tehreek, arranged to have his daughter and wife educated. He also encouraged them to engage politically.

When Khanzadi was young, her father moved the family to the village of Yaqoob Khatri, so she could pass her matriculation from a high school. When the head of their native village asked them to leave for good, the family settled in Fazal Muhammad Kapri. Even in the face of financial difficulties, Khanzadi completed her intermediate and graduate degree from a private college. Now, she works with an NGO.

When she spoke about last year’s floods, her words carried the weight of the devastation wrought upon her people. The torrential rains of July and August had submerged the villages in the Union Councils of Khuda Bux II, Mir Allah Bachayo, and Roshanabad. Khanzadi quoted an estimate which suggested that 208 villages in these councils were lost due to flood waters. “The road from Jhuddo and Tando Jan Muhammad that leads to UC Mir Allah Bachayo and Khuda Bux II was submerged in five feet of water,” Khanzadi said, “The villagers had to travel by boat.”

Khanzadi had been at the forefront of citizen-led relief efforts. She assisted with arranging tarpaulin and ration bags; she helped organise medical camps; she even cooked for homeless families. Much of this work was made possible through her political affiliation with Sindhyani Tehreek, a women-led organisation. Indeed, without political intervention, relief work is nothing but charity.

The lack of shelter and washrooms in flood situations can be particularly hard on women and young girls, Khanzadi pointed out. Last year, her team arranged for 3,000 sanitary kits to be provided to flood-affected women. They even arranged awareness workshops about harassment in relief camps.

“If you’re reporting about our grievances, do mention that no one from the district administration came to our rescue,” Khanzadi said, when we parted. “Everything that we did, in terms of relief, was done with the help of locals and organisations.”

The Master Plan

t a hotel near the city of Mirpur Khas, I had the good fortune of crossing paths with the journalist Shahid Khaskheli. Of the many horrific stories he shared with me, the most mind-numbing one was about a woman who had lost three children to the floods. She had sold the iron from the roof of her house to take one of the children to hospital, but it was too late. “If prostitution were legal,” she had told Khaskheli, “I would have sold my body to save my dying child.”

With Khaskheli, I also spoke about the law and its implementation. In 2011, the Sindh government had introduced an amendment to the Irrigation Act of 1879. It stated that immediate encroachments to natural water courses or channels must be removed. The directive applied regardless of whether there was a court decision, stay, grant, or lease associated with the land.

In 2013, the Sindh Irrigation and Drainage Authority (SIDA), an autonomous body, partnered with international organisations to develop a Regional Master Plan to restore natural waterways from Ghotki to Thatta. There was also talk about correcting the shortcomings of the LBOD system, which had been designed by the Water and Power Development Authority but handed over to SIDA for maintenance in phases from 1999 onwards.

According to Hizbullah Mangrio, a spokesperson of SIDA, the changing climate had messed up their plans. “The project was designed based on average rainfall data, which was 50mm for 24 hours at that time,” he said. “However, there have been environmental changes and the region has faced average rainfall of up to 100mm for 24 hours. This has caused problems.”

Mangrio claimed that local communities had been consulted for the preparation of the Master Plan. SIDA had organised seminars at the district, divisional and national levels, he told me, and people had been invited to present suggestions. “Six schemes were set up to fix things,” Mangrio said. “They included approaches to revive the LBOD, to restore natural waterways, to end land encroachments, and to save mangrove forests.”

At the time, this whole scheme was worth “ek sau bees arab” or PKR 120 billion. (Secondary sources suggest that the masterplan was worth PKR 7.2 billion.) However, the government decided that the amount was too large to be spent at once, and the project was split into phases. “The implementation process is ongoing,” Mangrio said. “Some encroachment issues have been resolved and some revival works have been completed. Others are still pending.” Mangrio also told me that SIDA is no longer in charge of the LBOD—that responsibility is now with the Chief Engineer Development II of the Sindh Irrigation Department.

The Six Maps

y path led me, at last, to the big city, the bustling metropolis of Karachi. I didn’t expect to find the Hakra or the Puran here, but I did expect to find its metaphors, which is what the city specialises in. And surely, I would encounter the ghosts of rivers past in a session hosted by the visual artist and curator Zulfikar Ali Bhutto Junior, who is named after his grandfather, founder of the Pakistan People’s Party and former prime minister Zulfikar Ali Bhutto.

At a university, Bhutto was talking about Bulhan Nameh, his ambitious research project to study the 10km stretch of the Indus that runs between Sukkur and Rohri. (Bulhan is a Sindhi word for dolphin.) The idea behind the Bulhan Nameh is to appreciate the Indus as a living, breathing river, and not just as an exploitable resource. The scope of the project is wide, and Bhutto’s techniques varied, ranging from traditional Sindhi embroidery to cyanotype on khaddar or khadi cloth.

The work I really wanted to talk to Bhutto about were the embroidery pieces informally called “six maps.” On 12x9 inches of khaddar cloth, and with thread and mirrors, Bhutto has traced the changing course of the Indus from 2500 BC to the present day. The numerous blue lines of the ‘final’ map are meant to illustrate the disastrous extent of the 2022 floods, and also point to the “value of a liberated ecosystem where water is free to drain into the river and finally into the sea.”

“When the British came to Sindh,” Bhutto told me, “they were shocked by the abundance of jungle and forest that stretched before them. Now, constructions like the Left Bank Outfall Drain, Right Bank Outfall Drain, and the Malir Expressway block the natural flow of rivers, disrupting the delicate balance of the land and the people’s way of life.”

Bhutto did not mince his words while talking about how the government, in collaboration with international organisations, has “sought to reshape the landscape to their own advantage, ignoring the needs of poor, indigenous communities, and the natural environment.”

He stressed the need to tap into the knowledge of local fishing communities like the Mohana to understand and preserve the natural flow of rivers. “The government’s actions are hypocritical,” Bhutto said, “They speak of climate justice abroad while ignoring the devastating consequences of their actions at home.”

Back to Square One

emember that I had promised to see Tara Chand again at the end of my travels? I made it back. The winds howled through the broken, mud-plastered walls of his home in Jan Mohammad Laghari, whipping through the empty space where a roof should have been. The floods had destroyed everything Tara Chand had grown, but now, he had spread his seeds again. After the displacement, the family had slowly made their way back home, having no choice but to rebuild.

Even now, the devastation was visible. The water ditches were filled with debris, and the memory of Tara Chand’s drowned son Mahaveer was still raw. His kacha ghar was nothing but a ruin. On the floor, there were chests that contained the family’s precious possessions, including Sindhi rillies—quilts—and blankets. Rebuilding the kacha ghar would cost at least PKR 40,000-50,000, a sum Tara Chand could not hope to afford.

All of this reminded me of a few lines by the Sindhi poet Ahmed Shakir:

Rain has engulfed Sindh and I am engulfed by my agony

The child tells me: the village has drowned after the broken levee

There is no one who can bring us bread and fetch water anymore

Inside the tent, the spectre of hunger stays alert and watches over

The father weeps after burrowing the ruins of the crumbled roof

Embracing the bodies of his deceased son and daughter

Grief has grown a beard in the span of a few days

Piece by piece he plays with us, Shakir, taking away all calm

This time, Gauri, Tara Chand’s mother, spoke about their ordeal. “When we were flooded, we ran for our lives and settled on a road,” she said. “But after three days, the road itself was flooded and we had to migrate again. We couldn’t light a fire because it was raining continuously. How could we cook food for our children? If we had sugar, we didn’t have flour. If we had flour, we didn’t have sugar.”

Winter had set in, but the family was short of warm clothes. That’s the difference between the rich and the poor, Gauri said. “Yes, everyone got flooded, the rich and the poor were equal then. But we don’t have homes, they do. We don’t have warm clothes, they do.” As I sat there shivering, my heart ached for the countless families of Sindh, families like Tara Chand’s. Their battle against the elements seemed unending.

Even as we adults spoke of these heavy matters, Tara Chand’s two daughters were playing in an open area in front of the house, their laughter a stark contrast to our despair. They were just happy to be back to the place where they had grown up.

Zuhaib Ahmed Pirzada researches and writes on climate justice, politics, fascism and capitalism. He tweets and tells stories @zuhaib_pirzada.