O

ne of Karachi’s most evocative phrases are the non-specific words “bridge ke uss paar,” the other side of the bridge. It refers to the metaphorical divide between the haves and the have-nots, but its physical manifestation is thought to be any of the several routes into Karachi’s Defence Housing Authority (DHA), an elite enclave and one of the first of the Pakistan Army’s enormously successful forays into real estate.

One evening this past winter, I found myself in a large house in DHA, where I met a man—grey beard, pink cheeks, soft voice—who told me about a death at a wedding in Lahore in the 1970s. That tragedy kicked off a series of events that changed the history of biryani in Karachi, and therefore, the world.

Sikandar Sultan’s mother was a Kashmiri married into a family from Delhi. She’d brought with her the Kashmiri practice of creating tikyas—sun-dried patties—from a blended paste of masalas: ground ginger, garlic, and so on. When it came to cooking a dish, the tikya was reconstituted in water. Before leaving Karachi for a wedding in Lahore, she made enough tikyas to last a fortnight but a sudden funeral delayed her return.

Her husband was a gourmand who’d installed multiple stoves around the house: no fewer than three outside the kitchen. When his children cooked something he liked, he gave them gifts. In his wife’s absence, he asked his children to take over cooking duties. It was then that young Sikandar was recognised as a special talent by the family.

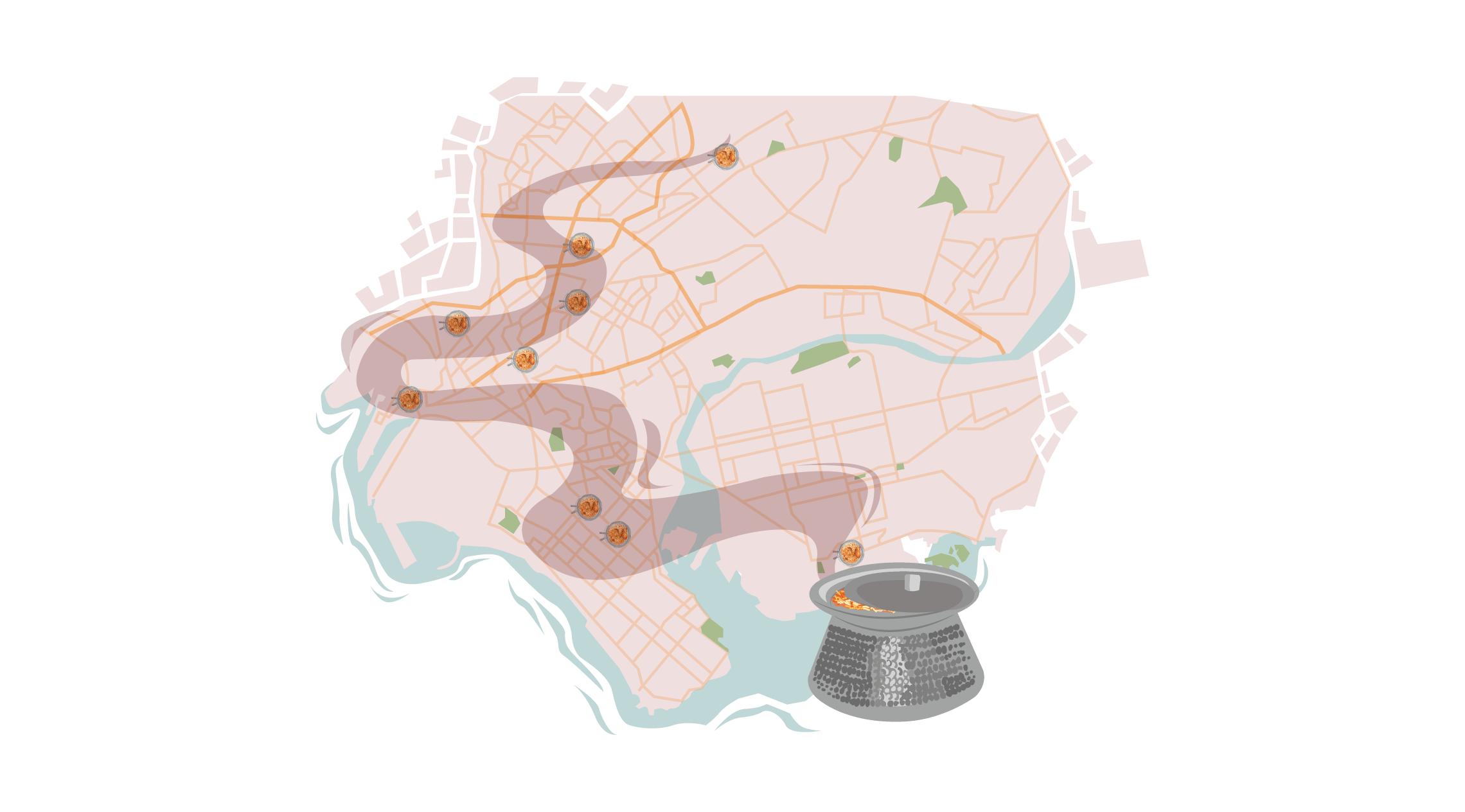

Building on his mother’s tradition of creating spice mixes, and learning from the experience of sending those to his sisters who moved abroad after marriage, Sikandar Sultan launched Shan Foods in 1981. Shan’s masalas ended up having an inordinate influence on biryanis world over, but particularly in Karachi. If you ask the city’s biryani-walas to name the types of biryani you can find in the city, you’ll hear: Delhi-style, Hyderabadi, Memoni or Gujarati, Sindhi, Bombay. The last two, as far as I could discover, are actually inventions of Shan Foods.

The biryani scene in the city was quite different in the early 1980s, Sikandar said. He counted three main varieties from the time: the lightly-spiced zafrani style from Delhi; a ‘wet biryani’ associated with the Kathiawari and Marwari communities; and the Hyderabadi style. “My wife is from Bombay,” he said, “so we made Bombay Biryani out of my love for her.”

As a romantic gesture for a spouse, I thought, it was an act second only to Shah Jahan’s. It was also an insight into his process. From early on, Sikandar and his family would profile the kind of people who’d like their blends. “We served endless people the same dish over and over again,” Sikandar said. The Bombay Biryani, which Shan Foods claims is an original variant and not like any version of biryani you find in Mumbai, was developed from the style cooked at Sikandar’s in-laws’, and then tested endlessly on them until it was perfected.

Similarly, the Sindhi biryani masala was inspired by the style of pulao made by the Sindhi workers at Sultan’s factory. Shan’s Memoni mutton biryani masala is developed from the Akhni pulao made by Gujarati-speaking Bantva Memons with their origins in Junagadh; their fish biryani masala riffs on recipes from Parsis and Aga Khanis.

All this research indicated that Shan were custodians of tradition, Sikandar Sultan claimed. He knew, of course, that there were pitfalls to standardising recipes. You can lose a legacy’s worth of culinary styles when a masala is put in a packet. “But the cost in terms of losing legacy comes at the cost of a woman’s freedom,” Sammer Sultan, Sikander’s millennial daughter, and co-chairperson at Shan,

pointed out. The advent of boxed masalas had drastically reduced the time required for traditional cooking.

I understood what she meant. My mother is one of many Pakistani women who has an intimidating sense of taste and belief in her own cooking skills, and Shan has long been a staple of her kitchen cabinet. Shan’s ‘packet masala’ also integrated seamlessly into her Panipat-born mother’s famed qorma recipe. Packaged masalas dramatically transformed kitchen work for women like her. In trying to preserve the traditions and tastes of biryani, Shan’s little boxes helped manifest more innovation, more jiddat, into biryani itself.