The day started early at 108, The Mall, Ambala Cantonment, a 200-year-old bungalow surrounded by a charming garden with roses in bloom and visiting birds. This was the address of the Hindi writer and professor of English literature, Swadesh Deepak.

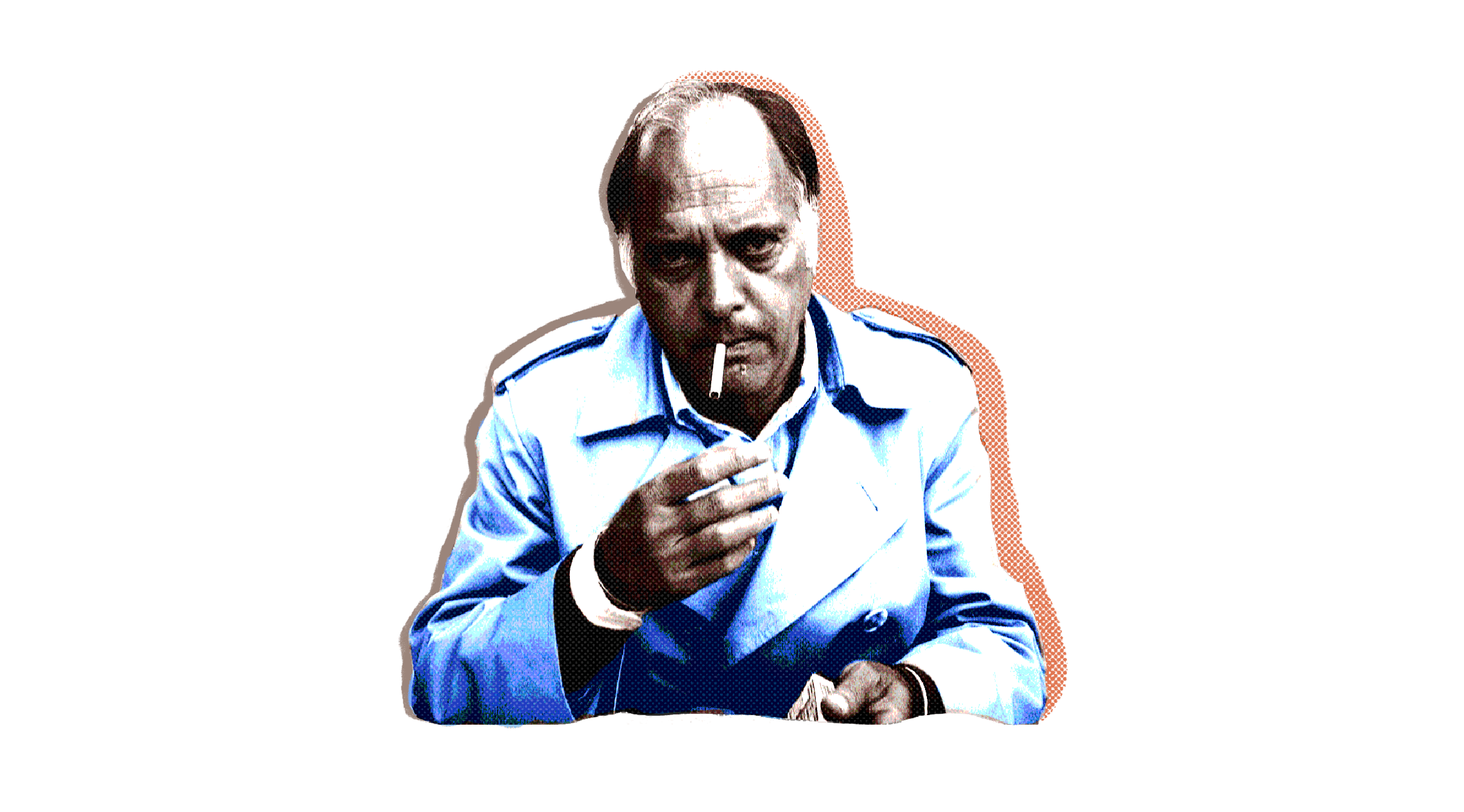

Swadesh had a fixed morning routine. He’d bathe, dress up, stop at a wayside stall for a cup of tea, and then again at a kiosk to replenish his supply of unfiltered Charminar cigarettes, preferred brand of poets, professors and the proletariat. On a bright summer morning in June 2006, he left number 108 a little earlier than usual. At the gate, he met a carpenter who did chores for the family. The householder Swadesh reminded him to deposit the electricity bill that day.

That was the last anyone heard of him. That morning, he neither had his cup of chai nor bought his Charminars. No one saw him walk down the Mall Road. He disappeared into thin air.

Swadesh Deepak: the man who followed his characters with a loaded gun, as the writer Mannu Bhandari once said. He wrote 17 books in all: nine collections of short stories, two novels, five plays and an astonishing memoir about living with mental illness titled Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha. The work that got him the most adulation was the play ‘Court Martial,’ which dared to examine class divides in the ranks of the Indian Army. It was translated to 12 Indian languages and performed more than 5000 times in the subcontinent. In 2004, it won Swadesh the Sangeet Natak Akademi Award.

Swadesh emerged as a playwright in the early 1990s, when Hindi drama was starved of original plays. Mohan Rakesh was long gone, Surendra Verma’s best had been written. In the theatre of the time, you either adapted plays from other languages or from Hindi fiction. Along came Swadesh, all set to change the old order. He was a rare Punjabi-speaking writer who stormed the citadel of Hindi writing and bewitched the Hindiwaalas.

The very first time I met him, I heard him rubbish literary Hindi for its pretension and niceties: “Hindi ko bhai-behan ki shaleen bhasha se nikal kar zindagi ke kareeb aana parhega.” Hindi literature needs to get out of its peaceable brother-sister mode and come closer to life.

That first meeting was accidental. I was a wide-eyed college girl. I had dropped by my older cousin Kamla Dutt’s home. Kamla was a US-based scientist but also a well-received short story writer. When I arrived unannounced at her doorstep as I was wont to do, she whispered that a major writer was visiting: Swadesh Deepak.

After he left, Kamla told me about his wonderful book of stories called Ashwarohi. I also remember her being shocked by his novel Mayapot, which was about a prepubescent girl trying to win her mother’s lover through the occult.

Back then, I had no idea Swadesh and I would become close friends, that we’d be brought together by a dard ka rishta, in the poet Faiz Ahmed Faiz’s words. A bond of pain. I did not know then that I would go looking for him when he disappeared.

We—his family, his friends, his fans—still wonder where he went.

wadesh was fascinated by trains, and many of his stories unfolded at the railway station and on train journeys. His own story began on a train, too. As a young boy, his family reached Ambala with hundreds of other Partition refugees from Kahuta in Rawalpindi, Punjab. (Many years later, Kahuta became home to Pakistan’s nuclear plant.)

The days that led up to that journey were traumatic for Swadesh. That was when the seeds of his dark storytelling were sown. One particular story stands out, told by his late younger brother Raj Kumar: “He watched his father, a teacher of Urdu and Persian adept in Greek medicine, taking to guns on the top floor of the village gurdwara. Hindus and Sikhs had gathered there to ward off the marauding crowds of looters and killers.”

Swadesh and his elder sister saw many fall, dead or injured. Many attackers were people the children had known as uncles in happier times. Their father was one of those who held the bastion of the gurdwara for seven days before running out of ammunition. If it hadn’t been for the Gurkha battalion of the army coming to their rescue, their story would have ended soon.

Swadesh’s father, Damodar Das, was from a gun-wielding, landowning clan in the picturesque mountain belt of Pothowar. The region was noted for its wildlife, hunting culture, and dashing, fair-skinned men and women. Swadesh had seen his father and grandfather use their guns—and not just for hunting animals.

The word ‘refugee’—‘rafugi’ in the Punjabi pronunciation—recurs several times in Swadesh’s stories. After the fall of the gurdwara and their rescue, Swadesh’s family were taken to a camp on the other side of the Radcliffe Line. (The Punjabi word for Partition is ujaarh, wilderness.)

This camp was in Kurukshetra, site of the great mythical battle of the Mahabharata. Damodar Das contracted tuberculosis here; it was said that the smoke of gunpowder and dust had caught up with him. He had to be moved to a sanatorium, and eventually had a lung removed.

Ambala city’s Baldev Nagar Camp, built by displaced populations, became the family’s next home, where they were cared for by Swadesh’s maternal grandfather. Swadesh only saw his father after five years. The reunion took place one evening, when he returned home from Baldev Nagar’s football ground. Sukant Deepak, Swadesh’s son, told me that he once asked his father why he didn’t play cricket or hockey instead. “No such luxuries for refugee boys,” Swadesh laughed. “All football required was a ball and a field.”

He simply sat there, feeling no pain, as the clothes he wore blazed away.

After Damodar Das’ return, the family shifted to Rajpura, a town built by refugees with the help of the Indian government. Here, they finally had a house of their own. In later years, while drinking with Swadesh in this house, his father would say: “I have no regrets about killing the killers. What saddens me is some of them were my friends. But they too had come with the intent of killing me. It was do or die.”

Damodar Das was a storyteller himself, and a Delhi-based Urdu magazine called Shamma was to publish the old man’s short fiction. Swadesh inherited this flair. His first job, during his college days, was as a writer-translator with the Air Force in Ambala Cantonment. It brought him in close contact with the forces and inspired his first novel Number57 Squadron, as well as ‘Court Martial.’ After he got master’s degrees in both Hindi and English literature, he took a job as a professor of English literature at Ambala’s Gandhi Memorial National College.

He used to take the train to commute to his job in Ambala Cantonment, and for years afterwards, he preferred not to take his two-wheeler for the 40-minute journey from his home in Ambala to his parents’ house in Rajpura. Nor did he take the bus. He chose to complete the journey over an hour, so that he could walk to the train station and get a leisurely cup of tea and a cigarette on the platform.

And it was a train he saw, slowly climbing onto the verandah of his home, when he set himself on fire in 1996. It was his third attempt at taking his own life. He simply sat there, feeling no pain, as the clothes he wore blazed away. In his memoir, he recalls that the train’s British guard gets off in front of him in that vision. “Where does this train go?” Swadesh asks him. The guard replies: “Nowhere.” Swadesh, precocious talent of the 1960s, climbs abroad, humming Eric Clapton’s hit song:

There is a train that goes to nowhere

Need no ticket for you to ride

Put you in a car they call the sleeper

It’s nice and warm inside

The days are never numbered

The nights don’t matter at all

Your time is no longer counted

This train has got you now

With some bulk, can’t get off

The pistons fates for you

There’ll be no friends with you now

The ride is just for you

ome nine or ten months after Swadesh’s disappearance, the phone rang at an unearthly hour at my residence in Chandigarh.

Milkhi Ram Dhiman, Ambala’s own theatrewalla, was on the line. “They know where he is but they are not telling anyone,” he slurred. “Swadesh’s family knows where he is but they are choosing silence.”

“Why would they hide it?” I was wide awake now.

“He’s written all about it in his new play ‘Judgement.’ The family is hiding the play and won’t show it to anyone. Swadesh used to keep the play under his mattress because he knew they had passed the judgement on him.”

“Don’t worry, Milkhi,” I said, intrigued. “I will ask his children.”

Milkhi and Swadesh went back some way. Swadesh was one of the most avid participants in Adhi Manch, Milkhi’s motley theatre group in Ambala. He was already a short story and novel writer whose work had been appreciated by icons like Krishna Sobti and Nirmal Verma. In Adhi Manch, he was reborn as a playwright. In fact, Milkhi directed Swadesh’s first play ‘Baal Bhagwan,’ which was about a physically deformed child being made the breadwinner of the family as a child god, the titular baal bhagwaan.

Later, when Swadesh had made some sort of a recovery from his illness, his theatre friend Kamal Tewari persuaded him to do a dramatic reading of his famous play ‘Kaal Kothri.’ Tewari was Milkhi’s senior in Haryana’s Cultural Affairs Department.

That day, the only light in the dark of Chandigarh’s Tagore Theatre shone on the author. A writing table and cigarettes were among his few props. The cigarettes had to be there—Swadesh couldn’t do without them. If I remember correctly, this happened sometime in 2000 so there was no ban on public smoking. The spellbound audience, which had seen the reading turn into a full-blown performance, gave him several rounds of standing ovations. “The billowing smoke added to the atmosphere,” Tewari said later.

Milkhi’s phone call left me unsettled. A few weeks after that, my friend Manmohan Sharma dropped by with another story of the missing writer. Manmohan, nicknamed ‘Panditji’ by my brother for his ultra-Left commitments, worked on all sorts of things: grassroots health programmes, farmer suicides, the sex ratio. Ours was a camaraderie of failed suicide attempts over lost love in our youth. We had both found out that it was hard to die.

Manmohan had just returned from a work trip to Rishikesh and Haridwar. In an ashram in Haridwar, he’d seen a picture of Swadesh in saffron robes and headgear, captioned ‘Swami Swadeshanand.’ The ashram people told him that Swadesh had taken jal samadhi in the Ganga some time before—voluntary death by immersion in water.

Manmohan knew Swadesh’s work, and had even met him once with me. In fact, that turned out to be one of Swadesh’s last meetings with friends and admirers: a nice evening in Ambala, with a congenial discussion about the forthcoming elections.

“Swadesh is a phenomenon of the times of the receding Left, when writers committed to the collective dream of revolution have become irrelevant,” Manmohan pronounced grandly on our way back to Chandigarh. “Swadesh has emerged as the radical individual, the hero of the times, because the reading republic cannot do without an idol.” I was used to such analysis, and didn’t take it too seriously.

But now this Swadeshanand business truly bothered me, more so when another nudge in this direction came from the well-regarded Professor Virender Mendiratta. Professor Mendiratta, who is in his mid-nineties now, has run a monthly literary meet called Abhivyakti in Chandigarh for many years.

Apparently, the professor made the announcement of Swadesh’s jal samadhi at one of these gatherings. I learned this from my older sister Kamla, who knew Mendiratta from when she’d acted in his plays in the 1950s. Swadesh and Mendiratta knew each other well, too, and Swadesh had read ‘Court Martial’ at an Abhivyakti meet. When he was recovering at Chandigarh’s Post Graduate Institute after the suicide attempt, Mendiratta used to fondly bring him apple stew.

Swadesh was never in denial of his mental health issues, but his friends like me were. Hearing about Mendiratta’s announcement was the last straw. I took it upon myself to get to the bottom of these rumours, despite the fact that two of my informants—Milkhi the natakwala and Manmohan the activist—shared a common love of Bacchus. It was not uncommon for them to see all kinds of visions after a few drinks. In any case, it would not be the first time I tried to barge into Swadesh’s castle of silence.

he first time was in the winter of 1996. I learned that he was ill but had forbidden friends to come see him. I was coaxed by Laali, the savant of Patiala. Hardaljit Singh Laali was a professor of anthropological linguistics at the university. He had devoted his life to the promotion of art and artists in our small town world.

“What happens is that a person first has a dialogue with others, and when that stops, a dialogue begins with himself,” Laali said to me. “But it is important that the dialogue be restarted, with the other or himself.” Laali had a smooth way of moving from life into art. “You look at Edvard Munch’s painting, ‘The Scream,’” Laali went on, “and you can see that a person is going to drown himself but all you can do is scream. You can’t save him.”

Laali knew that I was the survivor of a failed suicide attempt, and I guess he thought it might be good for Swadesh to be visited by someone from the same species. I’d even been admitted to the same hospital—PGI. As I write now, I remember my discharge card said I was ‘acutely psychotic.’ (‘Bipolar’ was not commonly used then.) If prescription drugs and counselling sessions failed, the card went on, we’d move on to electric shock therapy.

The great Krishna Sobti had driven all the way from Delhi to Ambala to meet Swadesh. How could I lag behind?

I survived without any of what was prescribed by the PGI psychiatry department, largely due to the kind advice of a psychiatrist visiting from abroad and the support of family, friends and colleagues. Looking back at how it went for Swadesh, I feel I let Laali down.

But back then, I was emboldened by Laali’s challenge to play the redeemer. Also, the great Krishna Sobti had driven all the way from Delhi to Ambala to meet Swadesh. How could I lag behind?

I reached the gate of 108, The Mall, on a chilly night. Swadesh, wrapped in a red and black Naga shawl, was walking down the garden path. When I waved to him, he raised his eyebrows. Perhaps he did not recognise me. But when I told him my name and where I was from, he escorted me warmly to his living room, and we talked for a long time.

He told me about the staging of ‘Kaal Kothri’ at Delhi’s Shri Ram Centre and his own mental state. Perhaps he thought me too soft to be told the story of Mayavini, the seductress who demanded his company to go to Mandu in Madhya Pradesh. I will tell you about Mayavini later.

Over that conversation, this was the reason Swadesh gave for his blues: he felt like a character in his own play. “I felt I was talking and behaving with the same rage that Rajat had in ‘Kaal Kothri,’” he told me. ‘Kaal Kothri’ was about the dark underbelly of the theatre world. Its protagonist was Rajat, who tussled with the meaning of his art and deteriorating relations with his family.

“I could not rid myself of repeating the line of Hamlet’s soliloquy that Rajat speaks on stage.”

What were the lines?

There is special providence in the fall of a sparrow.

If it be now, tis not to come.

If it be not to come, it will be now.

If it be not now, yet it will come.

The readiness is all.

Since no man, of aught he leaves, knows aight, what is’t to leave betimes? Let be.

So that was the first time I went searching for Swadesh. But on my second attempt, I had to approach his children to ask about the rumours surrounding his disappearance. I realise now how insensitive I was. I didn’t think enough about how the children were coping with their father’s going away, and their mother’s own sorrow and illness. Between all that, they had to retain their own sanity. (Geeta was diagnosed with cancer in 2000 and passed away in 2009, three years after Swadesh's disappearance.)

But I could not stop myself. Parul, Swadesh’s daughter, was a younger colleague in the newspaper world. When I met her at an event at the Chandigarh Museum, I said: “Parul, a friend of mine says that Swadesh went to an ashram in Rishikesh.”

She didn’t rebuff me. Instead, she said with an earnestness that was so like her father’s: “Yes, he is away. He has spoken to the family on the phone. He says he wants to be by himself for some time and will contact us later.”

I was closer still to his journalist son Sukant, who was 27 then. I called him.

“Sukant, Milkhi called to say that the family knows where he is but will not reveal,” I blurted.

“Milkhi must be drunk,” he replied calmly.

“I want to see the play that he was writing.”

“I will show it to you, Didi.”

“Sukant, your sister Parul told me he is in touch with the family.”

“Parul is telling lies,” he said in the same monotone.

I was a bit miffed that the conversation was going nowhere.

“Anyway, Sukant, I have decided that I am going to go looking for Swadesh.”

To this, he only had an entreaty: “Take me along with you, Didi.”

arul is the older one. Not only did she inherit her father’s manner of speech, she also got his cherubic looks. Sukant gets his sharp, chiselled features from his mother. Swadesh used to fondly dismiss his son’s face as ‘too perfect.’

Geeta Deepak was stunningly beautiful. She taught chemistry at Ambala’s Army Public School. She was from a Sikh family that migrated from Rawalpindi in 1947. She had met Swadesh when she was a science student at Gandhi Memorial National College, and defied her parents to marry the macho professor who was immensely popular with students.

Geeta’s family were the proprietors of ‘Mehta’s Gun Shop’ in town. Ambala has never lacked buyers for guns. I have already told you that Swadesh was familiar with weapons. He even bought a smart British revolver from his in-laws’ store.

Once, an uncle of Geeta’s came visiting from America, a man for whom the family nickname was Chacha American. Like most NRIs, he had a chip on his shoulder. This Chacha noticed Swadesh polishing his shoes every day. “Professor, do you polish your shoes every day?” he asked. The reply was: “Yes, I polish my revolver too.” Swadesh only ever used that gun once—to fire shots in the air—but he loved to polish it every Sunday.

I could tell you many stories of Swadesh and Geeta’s courting days. When her two brothers found out that she was seeing a college professor nine years her senior, they considered it their duty to accost him. Once, the two barged into Swadesh’s bachelor lodgings at an inappropriate hour, when Swadesh was having a drink with a journalist friend.

“We learn our sister is seeing you,” one said.

“Talk to her,” came Swadesh’s typical reply. “Why me?”

“You see, she wants to marry you.”

“Stop her if you can.”

Their sister was a headstrong individual. The older one’s tone changed to a pleading one, “You see, we are from a business family.”

“You are a family of shopkeepers. Kya sochte ho Tata-Birla ho tum?” Do you think you are a Tata or a Birla?

The brothers realised it was a losing battle. Later, they became very close to their famous brother-in-law. By that time, one was a doctor and the other an engineer.

shouldn’t go further without telling you a little about what made Swadesh such an extraordinary writer.

Swadesh’s first collection of short stories was published in 1973. The titular story was ‘Ashwarohi,’ the horsemen. It made his name. After Ashwarohi, editors wouldn’t stop sending him requests for a new story. Nor were they the only ones writing to him. Female fans mailed him in rapture, enthralled by his story about a handsome and sensitive man who, bogged down by patriarchy, ends up killing himself.

“Many of his female fans had to bleed to write those letters,” Geeta said to Sukant. “As though ink was not expressive enough!” Men wrote poems inspired by his writing and persona. This sort of fandom was the preserve of film stars like Dilip Kumar and Rajesh Khanna or poets like Majaz Lakhnawi or Shiv Kumar Batalvi. It was Swadesh who made the short story sexy.

At times, the postman would ask Swadesh who sent him so many letters. Swadesh would tell him: “My wife’s relatives have a lot of time so they keep writing letters to their dear daughter and son-in-law.”

In 1976, the leading magazine Dharmayug published his story ‘Kya Koi Yahan Hai.’ It was a cleverly crafted story, critical of the state apparatus. The metaphor was beyond the comprehension of censors, and they passed it without objection. Readers and intellectuals welcomed it with glee because they were starved of writing of this sort.

And we can’t talk about Swadesh’s short stories without mentioning ‘Bagugoshey.’ It is the title story of an anthology of eight that was compiled by his poet friend Soumitra Mohan in 2017, more than a decade after Swadesh’s disappearance. It gets its name from the juicy pears of Rawalpindi and is perhaps the only story he wrote about his mother, the cheerful Soma Rani. In it, the character of the mother visits her son to see if he is keeping well.

“Several Hindi fiction writers have dedicated a story to their mother, but Swadesh’s stands at par with the stories by writers like Kamleshwar and Mohan Rakesh,” Soumitra told me. Of these last stories, written between 2000 and 2005, Soumitra said: “They were written after a long stretch of disorientation and medication, when there was a constant death wish accompanying him. They are as beautiful as those written in his prime. Nowhere does he lose his mastery over language; in fact, the metaphor of these stories is stronger still.”

‘Bagugoshey’ is also remarkable because it manages to capture the spirit of the open house that 108, The Mall, once was. Swadesh’s students would walk in during their free periods, and make cups of tea for everyone in the house. “They even came in when Papa or Mama weren’t around, made chai or coffee, and sometimes an omelette or a scrambled egg for me,” Sukant recalled. “That was a lovely time, filled with laughter.”

Once, when Chacha American was visiting, he was horrified to see students waltz in and make merry in their professor’s home. “Have your students taken an appointment?” he asked Swadesh with a raised eyebrow. “This is not your wretched America, where students have to seek an appointment to meet their teacher,” Swadesh answered.

“Every day after college, I used to walk over to the compound of his home,” writer Shirin Anandita, who was his student in the MA class of 1990, recalled. “I’d have a glass of water or tea, and then walk to the opposite road to take a bus home to Ambala city.” Swadesh met his students outside home, too: they would huddle in The Little Chef café, close to college. It was where they had intense discussions and debates about the inner and outer world.

Y.M. Saini, who completed his MA in the early 1980s, became his closest companion and a friend of the family. “I did my BA and MA with him,” he remembered. “He loved teaching and went far beyond the prescribed course. An absolutely towering figure with equal command over Hindi and English.” Saini supported Swadesh through his illness, and there was even a time when he took his classes, because Swadesh felt he had lost his words. He had nothing to say to his students.

aini was with Swadesh in Kolkata when the writer had an encounter with a beautiful woman of the same age as him. It was a fateful meeting, for she—or at least the idea of her—would come to haunt his sleeping and waking hours. They were in Kolkata for the staging of Usha Ganguly’s production of ‘Court Martial.’ “He would never go anywhere without me,” Saini told me. “But he kept me out of his two meetings with this lady.”

Swadesh’s favourite writer was Sylvia Plath. When he was discharged after the fire incident, he started working on his own The Bell Jar. This was the memoir Maine Mandu Nahin Dekha. It is now available in English as I Have Not Seen Mandu, translated by Jerry Pinto. The woman he met in Kolkata was the one he would call Mayavini, the seductress. She haunts the pages of Mandu, because it is, after all, a book about Swadesh’s mind.

“I search for him after every play, hoping he is sitting in the last row and watching the show.”

He says Mayavini wanted to visit the city of Mandu with him, to see the love nest of the ill-fated lovers Rani Rupmati and Baaz Bahadur. Infuriated, he not only refused Mayavini but also insulted her, he wrote in Mandu. In return, she cast a spell on him. A light-hearted flirtation had taken the shape of black magic in his tempestuous mind. During his illness, much to the annoyance of Geeta and Parul, Swadesh would tell Sukant: “I am ill because I insulted her, because I refused to reciprocate her love.”

In the years of mental distress, another of Swadesh’s constant companions was Vikas Narain Rai, the writer and former director general of police (law and order) of Haryana. Rai had met Swadesh the day before he disappeared. “I called him and said I would stop by because I was driving from Chandigarh to Delhi,” Rai recounted. “What surprised me was that Swadesh told me not to come that day—not once but several times. But, knowing him too well, I insisted and he relented.”

The two friends had tea together and chatted. “But Swadesh was not in his usual kurta-pyjama, the one he wore at home. He was in a shirt and trousers, all ready to go out.” Rai asked if he was planning to go somewhere. Swadesh was quick to dismiss the query.

“He was always a perfectionist,” Saini said, as we spoke in the vast grounds of his home in the Cantonment. “Be it in his lectures or writing. And even the last act has left everyone guessing because he did it with perfection.”

Why am I telling you all this? I’ve not arrived any closer to an answer than I had back in 2006. I keep finding glimpses of him in people, places, things, in the way the human brain is wired to do when someone leaves, especially without warning. I know I am not the only one. There is theatre director Arvind Gaur, who keeps staging Swadesh’s plays over and over again, hoping he will find him in the audience. “I still don’t believe he is missing,” Gaur said. “I search for him after every play, hoping he is sitting in the last row and watching the show.”

There is also Amit Shukla, a hurt fan whose comment still floats around on the internet: “A country where if a star sneezes, dresses or does anything, it becomes national news. Swadesh Deepakji’s absence not getting noticed is something which raises questions on the effectiveness of mediums.”

The poet Soumitra Mohan does not participate in our collective hoping against hope. “If you read accounts of missing people,” he told me, “you will find that people imagine they have seen them. But this persistence shows insensitivity to a family that has suffered a lot.”

But, as it was in Swadesh’s life, so it is in his death. I can’t stop myself from thinking that I will see him soon. In Mandu, he wrote about me barging into his house. “Now, we will meet only after seven years in Delhi,” he wrote. “Niru has the habit of disappearing. She only reappears when she wants to.”

The same goes for you, Swadesh. We will meet again in Delhi, perhaps. I will spot you somewhere in your long coat and call out. We will stand by a kiosk near the National School of Drama. We will have chai and kebabs at the Shri Ram Centre cafeteria. Till that happens, I will keep meeting you in your stories. Yes, we will yet meet again.

Nirupama Dutt is a poet, journalist, and translator with over four decades of experience. Her works include the The Ballad of Bant Singh, a biography of Punjab’s Dalit icon; Pluto, a translation of Gulzar’s poems, The Poet of the Revolution, a translation of the memoirs and poems of Lal Singh Dil. She has received the Punjabi Akademi Award for her anthology of poems Ik Nadi Sanwali Jahi. Her poetry anthologies have been published in Hindi (Buri Auraton Ki Fehrist Se) and English (The Black Woman). Presently, she consults with the Hindustan Times in Chandigarh.