On a morning in May 2009, the people of Athara Beki village in West Bengal received an alert about a cyclone that had been named Aila. The village is about 25km from Canning town, the gateway to the mangrove forests of the Sundarbans.

As the skies darkened, they untied their cattle, picked up their children and headed to the schools that double up as cyclone shelters. But one man—the father of seven children aged between seven and 23—was reluctant to leave their one-room, thatched roof house, afraid of leaving it unattended while exposed to the elements. He stayed back with his wife but sent the children, including his 13-year-old daughter Ayesha, to the school shelter.

Ayesha recalled the winds pounding and the rain lashing angrily on the school walls. As Aila intensified, the cries of children and cattle inside the building grew louder. When the storm receded a couple of days later, Ayesha found her house in a sorry state: flattened roof, dismantled kitchen. Still, it was standing somehow. “Abba put bricks,” she said. “He brought mud from wherever he could manage to fix the house. He saved the house with a lot of effort.”

Floods and cyclones were not new to the Sundarbans. Many of Ayesha’s childhood memories feature her mother plugging holes in the roof with pieces of cloth, and arranging buckets and utensils on the floor. When they filled to the brim, Ayesha and her siblings would empty the vessels outside. Meanwhile, their father would guard the small tea stall he ran by the road. “Wherever you stood, it would be wet,” Ayesha said. “Things that you use to cover yourself would not be dry either.”

But something about Aila was unfamiliar, Ayesha said. She wasn’t wrong: Aila was a Category 1 tropical cyclone that reportedly rendered thousands of people in the Sundarbans homeless. Aid and doctors reached Athara Beki, but this time, Ayesha noticed desperation of a different degree. It took a month for her father to fix the roof of their house.

Abba was a timid man, Ayesha said. Around three years before Aila, he’d had to give up his rented tea stall after his brother got embroiled in a case relating to a political murder. This was around the time when another family member, who used to support the family by begging in the streets of Kolkata, went senile. Ayesha fondly remembered her as pagli daadi, the crazy granny—she used to indulge Ayesha with bindis, school bags and nail polish.

Ayesha, who was in Class 4 then, had to be pulled out of school, her mother’s meagre income from selling parboiled rice not cutting it. Instead, Abba brought her work: she would stick embellishments on clothes and get paid on a piece-rate basis. Soon, she also picked up how to cut threads and sew half-stitched parts on a sewing machine.

Aila left the Sundarbans devastated. Ayesha’s family was no exception: her parents had mortgaged her maternal grandmother’s jewellery to pay for a piece of land, and the interest was mounting. Then, as 2009 progressed, the family pushed Ayesha into a situation that transformed her life. “How does it feel when your closest people betray you?” she asked me.

Taoru Bazar

ver 13 years have passed since Ayesha spent about seven months in a village called Gawarka, in Haryana’s Mewat district. She was mostly restricted to a three-bedroom house, with an accompanying balcony and terrace. But she vividly remembers Taoru Bazar where she was taken a few times to get new clothes. Her eyes widened as she talked about a “bishal boro bazar,” a very big market.

Now, in Athara Beki, Ayesha’s house stands in a vast field. Next to it is a pond on which Ayesha and her four children rely for their daily chores. When I visited in June and December last year, Ayesha’s neighbours were curious about a city-based reporter coming to meet her, making a small interruption in the rhythms of daily life. Many women dropped by to exchange notes on chores. On their return from tuitions, Ayesha’s children demanded their share of puffed rice, which they dunked in tea to eat.

It was a routine day like this in Athara Beki almost 14 years ago, when Ayesha learned that her maternal uncle had fixed an alliance with a “well-established unmarried man,” one with “a lot of wealth.” Ayesha did not want to go with this man, even after her mother said that he would give her jewellery. But he showed up at the house the following day all the same.

“A well-built man with grey hair and few teeth,” she described him, her face contorting. “He looked five times my age and was wearing not a shirt-pant, but a kurta and churidar.” I didn’t push her further than she wished to go about his name or other identifying details. When she spoke of him, it was as “Buro Dadu,” the old man, or “Oi Bihari,” that Bihari.

Her relatives assured her they would not force her to marry the man. Instead, they proposed a trip. Ayesha is still processing what happened next. She recalled the yelling as her family discussed divvying up the amount of ₹1.5 lakh the man had allegedly promised them. Abba seemed to oppose the alliance, but her mother had the last word. A relative forced Ayesha to sign a blank piece of paper.

Ayesha was 13 years old then. Her case was not an anomaly in the region she comes from. A government report for 2019-2020 showed that the districts of South 24 Parganas and North 24 Parganas, home to the Sundarbans, registered 45 and 41 cases respectively under the Protection of Children from Sexual Offences (POCSO) Act, the second- and third-highest in the state after Kolkata district. [1] The 2020-21 edition of the same publication noted that the highest number of child marriage complaints were reported from these two districts taken together. The two districts also comprised over 40 percent of the complaints against missing children. [2]

After the signing, five family members took Ayesha to the train station at Canning. A series of journeys followed: Canning to Sealdah by train, Sealdah to Howrah Junction by road, Howrah Junction to New Delhi by train, Delhi to Haryana by road. In Haryana, her khala, her maternal aunt, housed them for a night.

Next morning, her khala and the other relatives told Ayesha that they were going to “see the mountains.” Instead, she was taken to a house where the grey-haired man was waiting. “This is your husband,” the relatives told Ayesha. Then, they left. “There were no celebrations, dressing up, or feasts,” Ayesha told me. “There was no kabul hai”—the acceptance that solemnises a Muslim marriage—“there was no exchange of signatures. It is as if it was a storm. Where do I go? Who do I talk to? I felt confused.”

The man left a cell phone with her family, and over the next few days, she spoke to Abba on the man’s cell phone. The thing she could bring herself to complain about was how difficult it was to make rotis, so different from home, where she was used to eating rice.

It was not the only thing she was upset about. “My heart wrenches thinking about that time,” Ayesha said. “Oder somman korechi, shraddha korechi, biswas korechi. Khub baje ora.” I respected them, and trusted them. They are terrible people.

Rape and Escape

ver the last year and a half, I’ve met at least 12 young women in the Sundarbans who’d become pregnant after being raped or trafficked. Ayesha was one of them.

The first time the man forced himself on her, Ayesha tried to run out of the room. But he tied her to the bed with the rope he used for his cattle. “When I bore his weight,” she said, “I would not be able to breathe. Even the weight of his hand felt heavy.” She used to scream in Bengali. [3]

“There was blood the first time he tried to have intercourse with me. This continued every day. My private parts would swell up. He would wait for it to subside, and then force himself on me again. I never liked the process. Now, I understand what it is for a husband and wife to like each other, to stay together. It never felt like I could go and hug him.”

What Ayesha said echoed something I’d heard from other teenaged mothers in the Sundarbans, even the ones who weren’t trafficked, in the strict sense of the term. The girls in arranged marriages did not use the word “rape” but they said they hadn’t “warmed up” to their husbands, or that they hadn’t been comfortable with sexual intimacy at the time they conceived.

Ayesha conceived within two months of being left at the man’s house. That’s when her parents visited her. After staying in Haryana for a month, Ayesha’s father insisted that the man should come back to the Sundarbans with them, so that they can conduct a proper ritual farewell for their daughter.

“My abba was a simple but smart man,” Ayesha smiled. The man caved in and they all made a train journey back. Once in the village, Ayesha’s father told the man that she would not return with him. The man, who was staying at a relative’s place in Howrah, was pressuring her father to let her go.

But she’d now become a laughing stock back home. “When you have been married to an old man, you have nowhere to show your face,” she said. “I was in distress in Haryana, but at least people did not know me there. In my village, I could not tolerate that everyone was asking me so many questions. Nobody would protest, they wanted entertainment.” When her mothers and brothers insisted she join the man in Howrah, she relented.

The torture intensified after Ayesha returned to Haryana with the man. He called her and her father names, beat her up, and continued to sexually violate her. She was not even allowed to use his cell phone. In Athara Beki, Ayesha’s father grew restless. He told his wife to get Ayesha out at any cost. Her mother managed to get Ayesha on the line after calling some of the man’s neighbours in Haryana. “Take some money and get out of the house when you can,” she advised. Her khala would pick her up from a spot.

Soon after Ayesha had been taken to Haryana for the first time, she learnt that the man had a wife, grown-up sons and daughters and even grandchildren. They lived in different houses. Now, the man was planning to bring his family back to this house for a while.

One morning in the summer of 2010, remembered by Ayesha as “the season when mango and jackfruit go ripe,” she decided she had to gather up the courage to leave. She moulded cow dung cakes, swept and scrubbed the floors, and curdled the milk for the first time in seven months. “That day, I managed the household like it was my very own, I behaved so well,” she remembered, breaking into a smile. When the man sat in the balcony smoking a beedi, she sat next to him. Suddenly, he asked her if he should head out for his usual business.

She had noticed the man place ₹5,000 under the mattress the previous night. When he left, she took the money, packed two sets of clothes in a small plastic bag and walked out of the house with her face down. In Taoru Bazar, she hopped into an auto. She got off at a petrol pump, paid the driver ₹500 and called her khala from the phone of an employee at the pump. She had a feeling she had attracted some attention, so she latched on to a man and his son until they reached another market. Her khala picked her up from there.

“I was scared he would find me,” Ayesha said, “I could not sleep or eat. My khala put me in someone else’s house for the night.” Expectedly, the man showed up at khala’s house that night but did not find her there. The same night, Ayesha’s mother and uncle had started for Haryana. In five days, Ayesha was back home in Athara Beki. She’d been gone for around seven months.

The “Bihari”

umaiya was born to Ayesha on 17 September 2010. It’d been a year and a half since Aila hit the Sundarbans. Ayesha wondered if she should return to the man in Haryana for the sake of her daughter, but this time, her family was more supportive, and assured her that they would take care of the child.

When Sumaiya began to speak, she took to calling Ayesha’s father Abba, and spent most of her time with him. When he offered namaz at the local mosque, she would sit next to him patiently. When he hesitated to give in to her demands, she’d tug at his long beard until he capitulated. Abba was her protector—especially against the others in the village who called her “Bihari” and other nasty names. [4]

Ayesha and Sumaiya were singled out for ridicule because Sumaiya’s biological father was an older man from outside the state, but early marriage and pregnancy is common in the Sundarbans and elsewhere in West Bengal. The scale of the crisis is borne out in the fact that the West Bengal government’s Victim Compensation Scheme has given out almost ₹10 crore to 450 children who’ve suffered sexual abuse since 2017. Children born from sexual violence remain outside the safety net of the government’s rehabilitation schemes, though there are isolated court judgements touching upon their rights.

Back in Athara Beki, income was sparse. The family had rented three sewing machines for ₹750 a month, operated by Ayesha and her brothers. Ayesha made more from sewing than the men did, but all of them pooled their incomes, and when Ayesha insisted on buying dresses and shoes for Sumaiya, the family agreed to give her ₹500 a week.

Family dynamics were changing quickly. Ayesha’s brothers got married, and there were more mouths to feed. Then, in 2020, when Sumaiya was around nine, her grandmother sent her to Kolkata to work as a domestic worker for a monthly wage of ₹1,000. The owners beat Sumaiya up when she picked up a fight with another house help. Ayesha went to Kolkata and brought Sumaiya back. Then, the pandemic struck and Sumaiya’s schooling came to a halt.

By this time, Ayesha had a lot more on her plate. When Sumaiya was around five, she had married a man from a neighbouring village, someone her family settled on because the groom’s family made no demands on them. She’d felt “no love,” she told me, and her new husband’s behaviour did not inspire any. She had work, but he didn’t. He had opinions about family planning, and when he found out that Ayesha hid contraceptives inside a steel jar of rice, he beat her black and blue. It didn’t take long for Ayesha to feel like the marriage was a mistake. But after the years of stigma that she had been through, she felt like there was no exit route.

One night, Ayesha saw her husband touching Sumaiya inappropriately. When she confronted him the next morning, he accused her of conspiring against him and asked her to send Sumaiya away, something she had to do. “He could not tolerate her,” Ayesha said. “When I gave her food to eat, he would be irritated.” Eventually, Ayesha had three children with her husband: two sons—aged six and two and a half now—after a daughter, aged seven. There were three more cyclones to come.

Bulbul, Amphan, Yaas

yclone Bulbul struck in November 2019, when Ayesha was still living with her in-laws. The gusty winds blew away the straw roof of the dwelling, and Ayesha worked on fixing the roof and her marriage. But by May 2020, when Amphan hit, she was no longer trying. She’d left in February, and rode out the storm at a brother’s home.

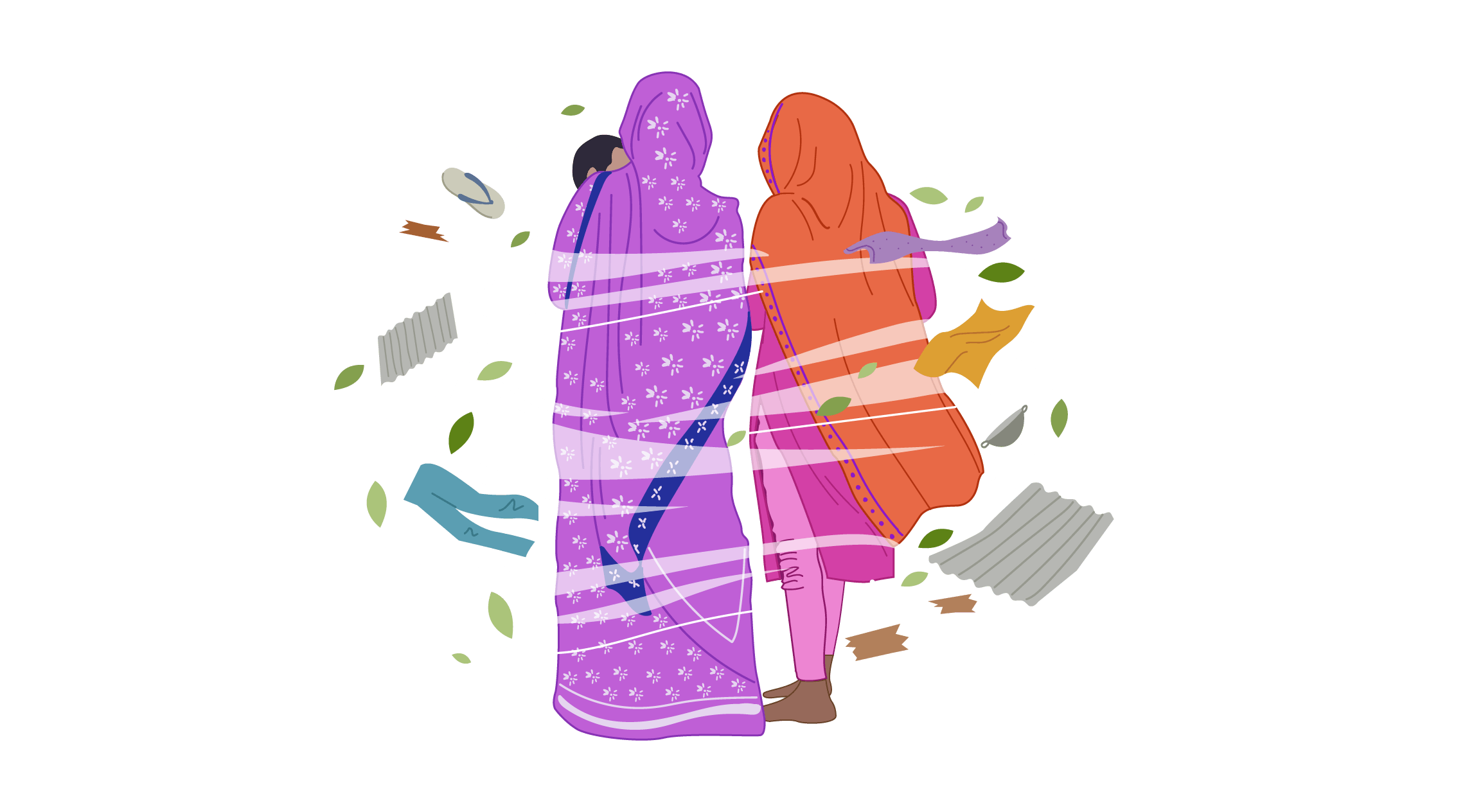

In the days that followed, West Bengal’s chief minister Mamata Banerjee said that the North and South 24 Parganas districts had been most affected by Amphan. When Ayesha had left her husband, her Abba had given her refuge in their ‘ala,’ a one-room structure that houses the caretaker of a fish-pond. When she returned there after the storm died down, she saw that its roof had blown away and her clothes were strewn all across the fields.

Ayesha and Sumaiya fixed the roof and stayed there, without recourse to alternatives. The shelters were overcrowded and aid distribution had been disrupted by the pandemic: there were days when they barely managed to eat one meal. When her youngest son was born, he was underweight, because of the lack of nutrition during Ayesha’s pregnancy.

It wasn’t all devastation. After Amphan, Ayesha’s father received a house under a Union government scheme. In the years following Aila, the family had saved some money to buy 22 asbestos sheets to firm up their home, and make it more “pukka.” Now that her family had a new structure, Ayesha took 10 of these sheets and used them to build a house on another small piece of land owned by her father.

Ayesha was weary from weathering Amphan, Bulbul and the frequent flooding in her village. As she let her guard down, and tried to focus on her life, super cyclone Yaas breached embankments in the Sundarbans and flooded large parts of the delta in May 2021. This was followed by another set of floods in July. When Ayesha and Sumaiya returned from Abba’s home after wading through chest-deep water, they found that rodents had eaten almost two drums of rice. Little did she know a fresh tragedy was around the corner. On 13 July, Abba died.

Bird’s Nests

ealth economist Barun Kanjilal, who has worked on the Sundarbans for three decades, told me that “climatic insecurity disproportionately affects women and children.” “A child is born with a number of rights,” Kanjilal said, “It is on the government, society and parents to protect these rights. In the case of the Sundarbans, all these three institutions have simultaneously failed. Households are breaking up due to migration and livelihood insecurities, the community network has weakened and the government has grossly failed.”

Ayesha was stoic about the changes she was living through. [5] “We will be in distress on those few days of a natural calamity,” she said. “See animals and birds on trees. Just like they suffer and accept their fate, we have to do the same, as human beings.” In another conversation, she compared homes in the Sundarbans to bird nests. “You have to rebuild it once it collapses.”

But rebuilding isn’t easy, and each devastation left her with fewer resources. After Yaas, Sumaiya’s grandmother brought up Kolkata again and found her employment for a monthly wage of ₹2,000. Sumaiya gave the money to her mother, but Ayesha was still conflicted about sending her daughter to Kolkata. She ended up having massive rows with her mother. Sumaiya returned home to Athara Beki in a month.

In September 2022, when Ayesha raised a hand to her, Sumaiya reacted by getting into an autorickshaw and declaring that she was going to the city. She went to the Jibantala police station, some 15km from Athara Beki, to complain about her mother and grandmother. “I told the police my nani had promised my mother that she would take my responsibility. But she did not. The police called my mother to the police station.” The police told Ayesha to take good care of Sumaiya, and let them return home together.

Now, Ayesha worries most about the recurrence of her own private devastation. “Sumaiya will be sold off by the family,” she told me. “If they see any profit, they will try to sell her. But she is not the type of girl who would listen to people. What will happen to her is unimaginable.” She’s been trying to work out how she can send Sumaiya to a care home.

Growing Up Too Fast

first met Ayesha at the Canning-based non-profit Goranbose Gram Bikash Kendra (GGBK) in June 2022, where I was interviewing young girls and women who had suffered sexual abuse as minors and had conceived from violence. I also met Sumaiya on that trip. In December, I returned to meet them in Athara Beki. In the intervening months, we spoke regularly on the phone. That’s how I got to know Sumaiya better.

Not yet 13, Sumaiya easily swaps innocence with a worldly-wise demeanour, mild manners with expletives, indifference with warmth. Often, she appears wise beyond her years, equipped with a confidence to take on the world alone. During my December visit, she showed me the vegetable patch she has been tending to in the stray land behind the house before animatedly holding forth on varying property prices in cities and villages. The one person she loves unconditionally is her youngest half-sibling: she brings cake on his birthdays, feeds him the khichdi provided by the integrated child development centre, and worries about his weight.

When I first met her in June last year, she said she dreamt of a life outside the village. In that vision, she is growing up in a hostel with children her age, far away from her village and half-siblings. On some days, she wants a father to shield her from the world. “Once in a while, when my mother gets angry,” she told me, “she’ll say, ‘I did not like your father, so I do not love you.’”

The day before my visit, Ayesha told me, she’d asked Sumaiya to help out with household chores. When Sumaiya didn’t budge from the game she was playing on her smartphone, Ayesha made as if to hit her with a broom. Sumaiya hit her mother and threw the broom in the pond. When Sumaiya’s anger ebbed, she collected some basic supplies, went behind the house with two of her friends, and lit a fire. The three children cooked potatoes, turmeric, chillies and salt in a vessel, and then poured it on puffed rice to eat.

But things got tense again. Ayesha had lashed out at Sumaiya, blaming her for her miseries. She was the daughter of a buro dadu—an old man—she told her.

“Did you not think before giving me birth?” Sumaiya had retorted, “Did you not remember this while sleeping with him?”

When I visited, I heard Sumaiya’s half-siblings call her “Bihari.” Sumaiya retaliated by referring to them as the “children of an alcohol and drug addict.” The younger siblings vied for Ayesha’s attention and complained about Sumaiya hitting them.

In between, routine took over, bringing its little joys. Mother and daughter chatted about the amount of ginger in their tea, the consistency of the daal and how they should cut the pui saag for lunch. When we ate, Sumaiya was all praise for her mother’s cooking. Ayesha said that Sumaiya often told her she could easily earn ₹25,000 by cooking meals in city households. “Even if I pluck saag and cook,” Ayesha beamed, “my children will keep licking their fingers.”

It weighed on Ayesha’s mind that Sumaiya was so different from others. “She is normal, but always fighting,” she said to me. “She has a lot of pain.”

“Ayesha is so scared of her daughter meeting the same fate as hers,” Subhasree Raptan told me. Subhasree is a senior programme manager at GGBK, which works with survivors of trafficking. “Ayesha wants to send her child to an institution because she cannot trust her surroundings. Hers is a case where the instances of child labour, child trafficking in the name of marriage, and rape have come together.”

Studies have shown that early-life sexual abuse affects later-life parenting, resulting in a difficult relationship between the mother and child if left unaddressed. Matters can be especially challenging if the child was born to a trafficked or abused parent. “Biologically speaking, stress can be transmitted from one generation to the next,” said Patrícia Pelufo Silveira, an associate professor in the Department of Psychiatry at McGill University who specialises in childhood adversities. “Child trafficking followed by a precocious pregnancy is a gigantic trauma that can affect the way that the foetus will grow and develop. On the surface, we see individuals suffering with conditions like anxiety and depression, which can affect their relationship with their family and the community.”

Storm Before the Calm

yesha first visited GGBK in 2021, when her husband took away her ration cards. Gradually, as she spoke to activists and survivors at GGBK, she began connecting the dots between her trafficking—which masqueraded as child marriage—the exchange of money, and her immediate family’s role in the whole trail of events. She still calls it a “marriage” occasionally, but she is trying to check the habit.

Now, she wonders if she can build a legal case, and hold her mother and uncle accountable. But there are days when she second-guesses herself. “‘Maybe I am getting it all wrong?’ That’s what I think. ‘Perhaps my mother and uncle would know best.’” After our June meeting, she sent me a recording of a call she made to her uncle soon after. She is heard asking if there was proof of her marriage. When the voice at the other end says there is no proof, she says she knows it was not a marriage—it was trafficking, and rape.

“Toh ki korbi ekhon?” says the voice. What do you plan to do about it now?

Ayesha’s uncle confirmed that he’d visited Haryana, but said that it was Ayesha’s father who had given her hand in marriage. There was no proof of a ritual or ceremony, because there were “no celebrations” for any weddings in their area, he said. He maintained that the man who took Ayesha away was no older than 25 or 26. (“He looked slightly older—around 30—due to his good health,” the uncle elaborated). He insisted that there was no exchange of money, and also that Ayesha was not underage at the time she went to Haryana.

On most days now, Ayesha is confident that the worst is over. Now and then, she told me, she fears the hostility of her relatives. Her monthly income has dropped from ₹4,000 to ₹1,000 after her mother and brothers told the local contractor not to give her work. Ayesha claimed that was a retaliatory move after she brought back Sumaiya from the city and threatened to bring legal proceedings against the family.

In October 2022, she joined a training course for a group of women—survivors of domestic abuse, trafficking and child labour—at GGBK’s new centre. Despite only studying till Class Four, she told me, she’s trying hard to keep up with the class. On my December visit to the centre, I watched her juggle childcare with lessons on how to navigate formal interviews: her younger children accompany her to the centre.

When the trainer asked about professional goals, Ayesha said she wants to learn to sew clothes from scratch. Currently, she only knows how to put together semi-stitched parts. “I want to teach sewing to women in my locality,” she said, “I will start from my home. I will charge each person ₹100. I will start at a small scale, and then see how it goes.”

But, as before, her mood darkened quickly. Sumaiya wanted to buy new clothes to go to the local fair, and asked her mother to call a contractor for the week’s payment of ₹400. When they received it, Sumaiya felt it was not enough. She blamed her mother for depriving her of a happy childhood.

“I am a mother,” Ayesha told me, “I understand the situation. But will she? When other children will have access to food, education, a mela, movies, things will be tense. It is because of deprivation that there is so much hostility at my home.”

Ayesha and I speak often these days. Lately, her calls to me are peppered with English words she is learning at the centre. Even over a poor network, her excitement during a call late last year was palpable. She had managed to fast-track the termination certificate from Sumaiya’s school where she was enrolled in Class 7, and had completed the formalities before a Block Development Officer in Jibantala to start the assessment process before her daughter could be sent to a care home. [6]

Their past haunted them, the present drove wedges between them, but Ayesha and Sumaiya agree on what they seek from the future. Both want justice. Before I left their house in June last year, Sumaiya declared that she will grow up and join the police force and course-correct everyone around her.

“You will grow up to be a goonda,” her mother said indulgently.

Ritwika Mitra is an independent journalist.

Sumaiya and Ayesha are pseudonyms to protect the identities of the survivor and the minor.

This reporting was supported by the Dart Center for Trauma and Journalism’s Global Early Childhood Reporting Fellowship.