On 3 December 1952, a hastily organised trial opened in the nondescript town of Kapenguria, close to Kenya’s border with Uganda. The action unfolded in a classroom in a small school, fenced off by barbed wire. Kenya’s future president Jomo Kenyatta and five others were in the dock. They were charged with leading the Mau Mau, a rebellious organisation allegedly committed to killing the white settlers of British-ruled Kenya.

The “Kapenguria Six” were leaders of the Kenyan anti-colonial uprising, and they attracted a formidable defence team. A motley crew of lawyers from across the Commonwealth assembled there at the initiative of the Kenya African Union (KAU), the party of the Kikuyus, Kenya’s largest ethnic group. The team was led by Denis Nowell Pritt, a British lawyer whose previous clients included the Indian revolutionary trio of Bhagat Singh, Sukhdev and Rajguru; and the Vietnamese statesman Ho Chi Minh.

Dudley Thompson came from Jamaica and H. Oladipo Davies from Nigeria. At Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru’s recommendation, Diwan Chaman Lall had arrived from India. He was not, however, the only ethnic Indian on the team. There were also three young Indians who had grown up in Kenya: Jaswant Singh, F.R.S. de Souza, and a lean, bespectacled 26-year-old called Achhroo Ram Kapila.

The Kapenguria Trial was the making of a singular figure, in more ways than one. Kapila, on whose deep knowledge of East African case law Pritt relied for the Kapenguria trial, went on to have an historic career. He defended many more presidents and chiefs, and participated in cases crucial to the political destiny of his part of the world.

By virtue of both his location and vocation, Kapila had a front row seat to decolonisation in East Africa. He was close to political power, though he never held it. He preferred to ride the currents of history, even when they turned against him. Most notably, this happened after Kenyan independence in 1963, when Kenya’s Africanisation policy formalised a gradual othering of the Indian community, who were seen as brokers of the colonists, not wholeheartedly invested in African emancipation.

As a lawyer, Kapila defended the values he had seen succeed in the independence movement of India, his country of birth. But when the balance of power shifted, he found himself sidelined, many times by the political powers he’d defended against British brutality. His fight was for a just world. But in a society that had been racked by staggering inequality for so long, justice meant different things to different people.

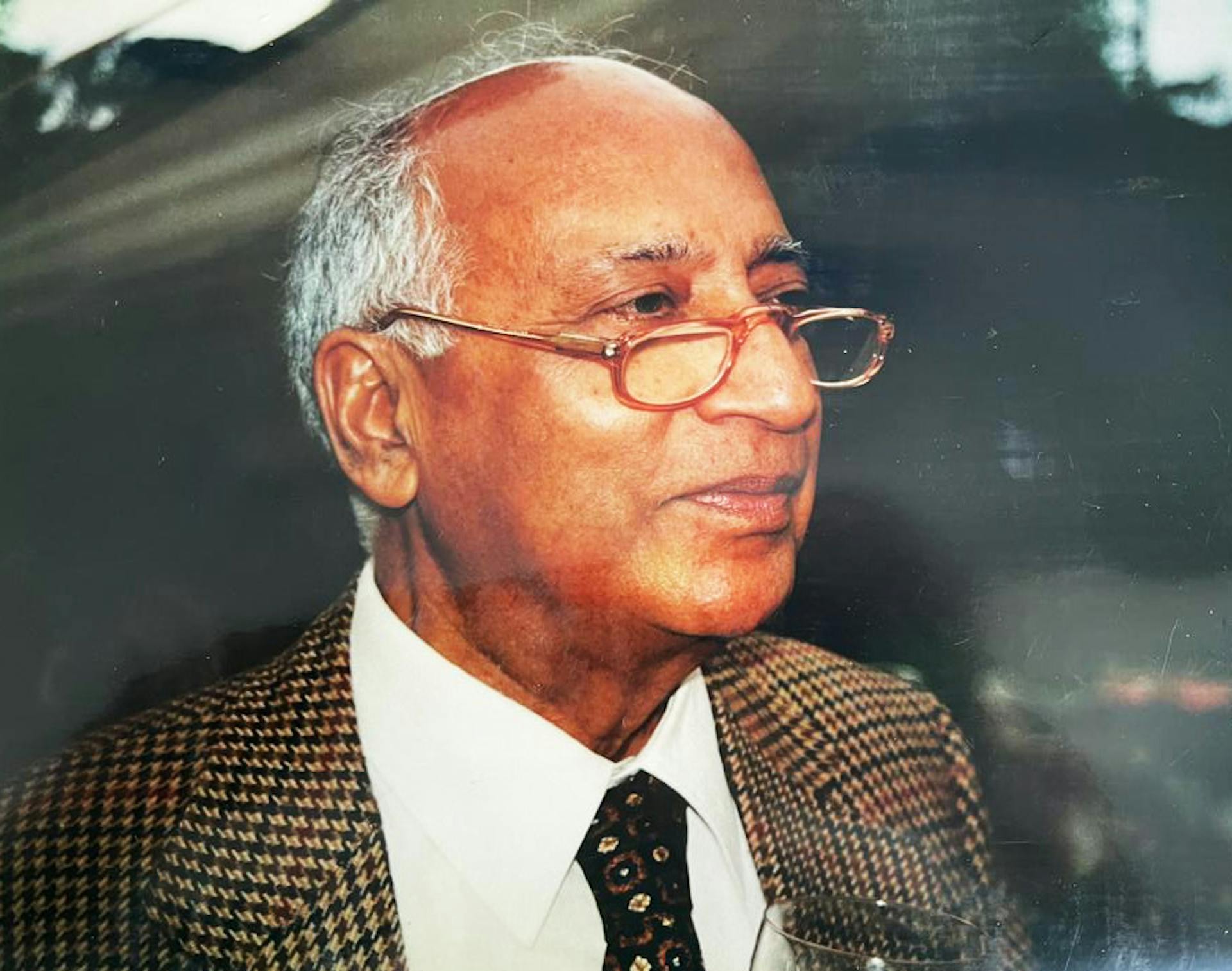

In 1997, Kapila was the first recipient of the Distinguished Service Award, awarded by the Law Society of Kenya. Credit: Sheetal Kapila.

London, Return, Segregation

doctor cousin of the Kapila family had recommended Kenya as a good place to live: good climate, fertile soil, jobs aplenty. When Achhroo was four years old, [1] his father Salig Ram moved the family out from Ludhiana to fresh pastures. It was 1930, just the beginning of a dark decade in world history.

In Nairobi, Salig Ram set up a law practice and made a name for himself defending Africans accused of race-related violations, such as breaking residential area curfews. It was a time when any act of protest was booked as dissidence by the authorities, but Salig Ram unhesitatingly took on cases involving the KAU.

Achhroo studied at the Government Indian School in Nairobi where he was touched by the nationalist fervour blazing through India in the 1930s. His son Sheetal told me about the time when his father, ring-leader of a group of boys, called for a day-long strike after the British principal ordered the removal of a portrait of Mohandas Gandhi that someone had hung next to a picture of George VI.

Achhroo followed in his father’s footsteps, though the Second World War meant that he had to begin his London law degree through correspondence. When he finally went to England in 1946, he experienced a subtler form of discrimination than he was used to in Kenya. People stood up wordlessly when he sat down next to them on the bus. Such events, he later said, “cut him more” than the entrenched segregation in Kenya.

He returned to Kenya in the following, tumultuous year. India finally achieved independence in 1947, an event that had a ripple effect across the Indian Ocean and galvanised Kenya’s leaders in their own battle against the same coloniser. Nehru had emerged as a shining example of a statesman committed to progressive and modern principles. Since the 1890s, democratic arguments from Britain’s largest colony had made their way into East Africa, helped along by emigration, which some viewed as an extension of a long historical connection fostered by trade. Harry Thuku, an early Kikuyu leader, was openly inspired by India’s freedom struggle and Gandhian methods of satyagraha.

But Achhroo Ram Kapila saw that the differences between Kenya and India were stark. Colonialism’s belated appearance in Kenya had created a more unequal and segregated society. The rural economy of colonial Kenya was different, too. Here, white settlers—British, Boer, European—held vast tracts of fertile land in the Kenyan highlands and dominated the Imperial Legislative Council. Indians were concentrated in the cities like Nairobi and Mombasa. Ethnic Kenyans were subject to the stinging indignities of the kipande system—passes that regulated their entry into cities and in European settlements.

And there was hardly any intermingling between all these different ethnic groups. Sukrita Paul Kumar, a writer and translator who grew up in Nairobi in the 1950s, told me about how “invisible” Kenyan Africans used to be, even in Indian homes, where the householders could not be bothered to pick up more than a smattering of Swahili, enough to issue instructions. Her father, the Urdu writer Joginder Paul, was distressed at the treatment of African “houseboys,” as male domestic workers were called. It’s hard not to draw a parallel with the way the majority of British colonial administrators ran their own households.

The ethnic resentment against colonial expansion first grew over land. From the 1920s onward, organisations like Thuku’s East Africa Association were speaking up for political rights. In the 1940s, the resistance grew stronger, especially with the formation of the KAU. The British often embroiled KAU members in legal tangles, an old tactic to kill the momentum of dissent and break the spirit of individual activists.

Into this cauldron, newly called to the London bar, stepped Achhroo Ram Kapila. By the time he joined his father’s practice in Nairobi, he knew the world had changed forever. The war had beleaguered European colonial powers, and Kenya was bubbling with hope, resentment and repression. Father and son went to work defending political prisoners and outspoken dissenters.

In 1950, an Indian communist and activist named Makhan Singh triggered the British authorities by organising Kenya’s Trade Labour Union on multiracial lines. Singh opted for a long jail term over deportation, and it was Kapila, as Singh’s lawyer, who mediated with the authorities. The year of that case was also a personally meaningful one. When he was being driven around Nairobi by a friend, Kapila glimpsed his future wife at a bus stop. Krishna was 18, from the Assanand family that owned a chain of music shops in Mombasa, Nairobi, and Dar es Salaam. They would go on to marry and have three children: Sheetal, Ishan and Madhvi.

Kapila’s legal career, meanwhile, was marked by a series of firsts. In one matter, he defended a Kikuyu man who had been assaulted by Chief Makimei, a British loyalist. It was the first instance when a chief, a figure venerated in Kenyan societies, had been summoned to a British courtroom. In October 1952, Kapila defended those accused of assassinating Chief Waruhiu, yet another loyalist. Gathuku Migwe, one of the two men given a death sentence, was Kapila’s client. He was shattered: Kapila was, and remained, a lifelong opponent of the death penalty. Sheetal told me that when Kapila visited Migwe in prison, the convicted man had to console his feisty lawyer.

But it was just few weeks after the Waruhiu assassination case that Kapila would get embedded in a case that changed his fate—and that of the nation.

Kapenguria, Mau Mau, Spectacles

omo Kenyatta, Bildad Kaggia, Fred Kubai, Kung’u Karumba, Achieng’ Oneko, and Paul Ngei: these were the Kapenguria Six. They had been arrested during the nationwide ‘Jock Scott’ operation on 20 October 1952, [2] undertaken to stifle dissent against the regime.

One of the charges levelled against the Six was that they were members of the Kenya Land and Freedom Army or the Mau Mau, a guerrilla organisation committed to resist British rule with violence. The prosecution alleged that it had evidence that the Six had participated in the Mau Mau’s dramatic oath-taking ceremonies. The ceremonies had taken on a vivid significance to colonists: the oath was marked by the ritual slaughter of a domestic animal and smearing oneself with its blood. Members promised to never betray one another, nor to sell land to a white man, and to use violence if commanded.

The charismatic Kenyatta had studied at the London School of Economics and returned to his homeland in 1946, a year before Kapila. The two had struck a friendship of sorts in the 1940s, no doubt necessitated by the frequent arrests of KAU members and the need for a brilliant lawyer to defend them in court. Kenyatta was often in Kapila’s chambers, then one of the few places in segregated Nairobi where non-white people could meet informally. [3]

The Six claimed that they had no connection with each other. Still, they were arrested—and Kapila was the obvious choice to defend them. All his experience so far had led up to this test. The arrests, he thought, were a final attempt by the threatened regime to tighten the grip on its privileges. In every aspect, the trial mirrored the changing world order. To Kapila, it offered the tantalising glimpse of a just and equal postcolonial world.

So it came to be that he found himself in a car with the famous Denis Pritt on New Year’s Day in 1953, heading towards Kapenguria, an “obscure village in a wilderness.” [4] The car skidded and overturned near Eldoret, about 70km southeast of Kitale, the nearest town to Kapenguria. Pritt suffered minor injuries; Kapila was unharmed but he couldn’t save his black-framed, thick-lensed glasses. While Pritt was treated by a doctor in the closest town, Kapila made the seven-hour journey to Nairobi for a spare. He was back the next morning.

The British did everything they could to inconvenience the defence team. They surveilled them as they travelled on dusty, unpaved roads. On one occasion, a team of motorcycle riders armed with shotguns accompanied their car from Kitale. Often, the lawyers heard the drone of light aircraft overhead. [5] The men found no accommodation in Kitale until an Indian businessman offered them his home.

The hostility spilled over into the legal process. The British did not provide case papers to the defence team, which was allowed to meet the clients only for a brief half-hour at the end of every court day. They had limited prior information about the witnesses—bribed and tutored—that the government would call.

Meanwhile, the campaign against the Mau Mau continued unabated. Reports of Mau Mau attacks on settler families prompted brutal retaliation. But casualties among ethnic Kenyan groups were far higher. Entire communities were separated and moved into detention camps. Santha Rama Rau, writing for The New York Times, noted seeing one such detention camp from the terrace of a friend’s Nairobi home.

The prosecution witnesses were not the only ones to be allegedly coached. The British had persuaded Ransley Thacker, the presiding judge, to come out of retirement. Later reports established he had been bribed heavily to pass a harsh sentence. [6] The testimony that sealed the jailed men’s fate came from a man named Rawson Macharia, who claimed he had been part of a Mau Mau oath-taking ceremony conducted by Kenyatta, who’d exhorted the use of violence. All six defendants were convicted, and sentenced to seven years in jail.

Yet, the trial of the Kapenguria Six burnished the credentials of the accused and their lawyers. Kapila, in particular, was lauded by the KAU. John Githongo, a Kenyan journalist, told me that Kapila’s “moral courage and his formidable intellect won him great admiration.” Pheroze Nowrojee, a leading Kenyan lawyer who once worked as Kapila’s junior, told me that the senior came out of Kapenguria with a deeper appreciation about the place judicial processes had in a campaign for political and civil rights.

Kapila and Pritt went on to do more work in high-profile political cases. In 1958, they defended Jaramogi Oginga Odinga, Tom Mboya, and Daniel arap Moi, who were among the first African members of the Legislative Council, against charges of political activity. The three leaders had boycotted the Council to protest against “racial-based” electoral reforms. That same year, in a sensational case, Kapila appeared for Macharia, the witness who’d appeared to seal the case against Kenyatta and the others at Kapenguria: Macharia confessed to lying at that trial. (He received a sentence for perjury.)

Kapila also wrote the legal briefs when Pritt defended Julius Nyerere, whose publication had been charged with deriding the colonial government in Tanzania. Nyerere, like Daniel arap Moi, went on to lead his country’s government after decolonisation. It wasn’t the first time Kapila was defending future presidents, and it was not to be the last.

Harambee, Uhuru, Domination

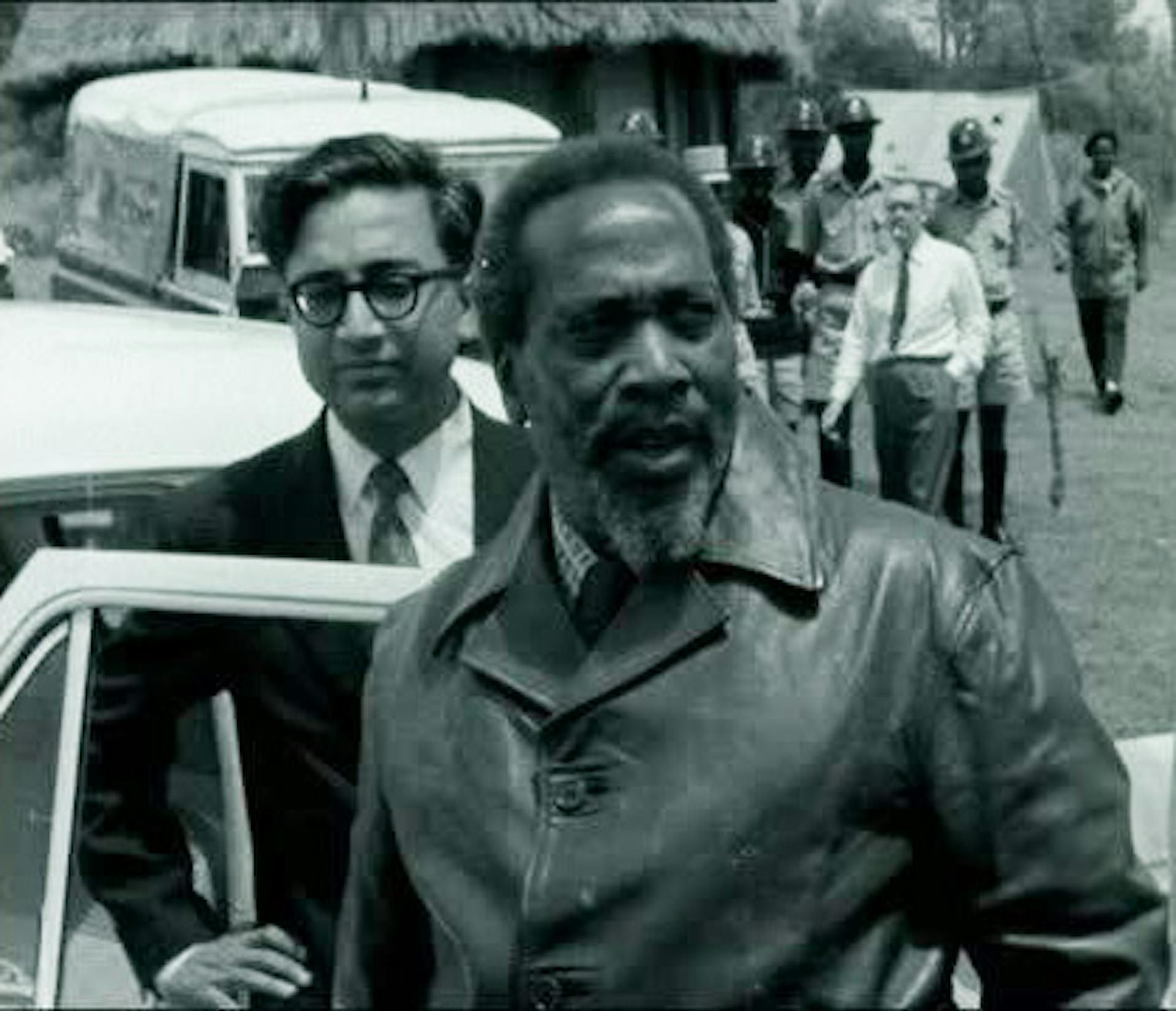

n 11 April 1961, Kapila was on Kenyatta’s right at the latter’s first press conference at Maralal, in central Kenya. At this press meet under a makeshift tent, [7] Kenyatta called for African unity and an end to violence. On 12 December 1963, Kenya finally achieved Uhuru: the freedom that the KAU and others had been fighting for since the 1940s. To build the young nation, Kenyatta declared, the need of the hour was harambee—Swahili for “pulling together.”

Kenyatta and Kapila in Maralal on the day of the press meet in April 1961. Courtesy: Suman Mahan’s collection.

Post-independent Kenya had to grapple with societal complexities and mend many fractures. KAU was renamed the Kenya African National Union, or KANU; Kenyatta, as leader of the party and now country, sought to govern by compromise and accommodation. As in many post-colonial societies, this was hard to put into practice.

Not long after, the government officially adopted the policy of “Africanisation,” with most ministries being divided between the different ethnic groups of Kenya. The minority Asian community—primarily Punjabis, Sindhis and Gujaratis who had migrated from undivided India—were materially more prosperous than the Africans. Relative to their economic contributions, they felt themselves underrepresented in the new scheme.

The historical background to this was that the community had split down the middle in the run-up to Uhuru. During the constitutional negotiations held in Britain between 1960 and 1963, the two main Asian representative groups—the Kenya Indian Congress and the Kenyan Freedom Party—failed to reach agreement on the future status of Asians.

The historian Sana Aiyar, who studied the Indian community in Kenya, explained there was a clear generational difference on such matters among Asians. The younger lot, who became politically conscious from the 1940s onward, saw themselves as committed Kenyans. Most among the older generation of Indians, while supportive of independence, were largely seen as collaborators and enforcers of the empire. Their scheme of gradual political reform included land-related privileges on par with the settlers, and greater representation of Asians in the Legislative Council.

Kapila’s was a rare position as a voice of conscience—and, starting from the mid-1960s, it was a somewhat uncomfortable one.

As KANU drilled down on its power, Kenya became a de facto one-party state. Opposition to Kenyatta’s Kikuyu-dominated regime by other groups and sections of the military was quickly suppressed. On some occasions, in unmissable irony, the clampdown was aided by British army regiments. Outspoken critics and challengers to Kenyatta were assassinated. One of them was the Goan journalist and KANU member Pio Gama Pinto, who was fatally shot in February 1965.

These developments may not have taken Kapila by surprise. From the first day of independence, he had an inkling that both him and Kenya were heading into an uncertain future. In his unpublished memoirs, he notes the time that senior KANU leader Joseph Murumbi arrived at his house in December 1963 to warn him of his absence from the guest list for the independence handover ceremony. The man behind this omission was Charles Njonjo, soon to be the all-powerful attorney general of Kenya.

Kapila took Kenyan citizenship after Uhuru, [8] but declined an offer for judgeship. It’s possible to speculate that he preferred not to be co-opted into the new system. His political masters would be men he’d defended and once considered allies, but that did not put him above danger. Whatever his reasons, this turned out to be a shrewd decision.

Africanisation, Immigration, Presidents

s his practice grew, Kapila moved to a house in Nairobi’s Lower Kabete area, a place that once had coffee plantations. He threw himself into things forbidden in more segregated times; he played tennis and golf at formerly white-only clubs, he sailed and learnt to fly a plane from a Polish veteran of the Battle of Britain. For the rest of his career, Kapila stuck to his forte of criminal defence.

Some influential functionaries of KANU, especially a cohort led by Attorney General Njonjo, saw him as a threat, but there was no denying his legal talent. In fact, he was viewed as a contender for leadership positions precisely because of his mastery of the court craft. His private practice boomed in the post-independence years, and people thronged the courtrooms to hear him speak and cross-examine witnesses in his measured, gravelly tones. His flamboyance and idealism sometimes went hand-in-hand. When appearing for cases in neighbouring Uganda, for instance, he flew his own plane down.

In a speech in May 1965, Kapila’s former client Tom Mboya, now a minister for economic planning, singled out the Asian community as disloyal neo-colonialists who were impeding economic growth and national integration. [9] While writing this essay, I recognised how interchangeable the idea had become with majoritarianism for a generation of Kenyans of Indian origin: speaking of the period, Pheroze Nowrojee described it to me as “Kenyatta-Kikuyu” domination; the author and editor Zarina Patel called it “Kenyanisation.”

The Kapila house in Nairobi’s Lower Kabete area. In pre-independence times, it was the site of coffee plantations. Credit: Sheetal Kapila.

Asians were accused of taking away jobs and other opportunities from deserving Kenyans. Asian civil servants were removed from their positions, and their contracts not renewed. Small businesses and merchant firms had to secure licences to operate, which were invariably delayed by the authorities. Kapila, along with several others from the community, petitioned against the onerous licence requirements, but to no avail.

Indians who held British passports were asked to become Kenyan citizens. Many Asians, influenced by what Sana Aiyar described as “push” as well as “pull” factors, sought a move to Britain. In contrast to Kenya’s new hierarchism, they saw themselves as part of a thriving multicultural Britain. Sukrita Paul Kumar recalled that hers was among the few families to return to India: most Kenyan Asians saw India as “backward” and “undeveloped.”

But Britain, on its part, was not so thrilled by the prospect of hosting Asians from East Africa. The subtle form of racial discrimination which Kapila experienced as a young law student in the 1940s took the form of legal euphemism. The Commonwealth Immigrants Act of 1968 kept Asians out without expressly saying so: free entry into the country now required a connection to a grandparent born in Britain.

In Kenya, Kapila and younger colleagues like Rasik Shah petitioned the British government, questioning delays in issuing visas. In a magazine article in 2004, Shah recalled the occasion when a young Indian couple was refused a visa by the British High Commission, and the guard on duty assaulted the woman. Kapila advised them to register a case against the guard. The matter was hushed up, and the visa issued promptly. [10]

At this time, Kapila was appearing for Milton Obote, the president of Uganda. Both Obote and the chief of the Ugandan army were accused of providing arms to rebels in Congo in exchange for gold. Kapila managed to secure an acquittal for Obote, but his co-accused was not exonerated. Yet, Obote continued with him as army chief. It was an ill-considered decision, because the army chief, Idi Amin, overthrew Obote in a coup three years later. One of Amin’s first decrees—the expulsion of Asians from Uganda—had a direct precedent in Kenya’s “restrictions” on Asians.

In Seychelles, an archipelago 1500 kilometres off mainland East Africa, Kapila and Nowrojee represented Albert René, then leader of opposition and future president. René had been charged after a bomb had gone off at the new international airport, weeks before its inauguration by Queen Elizabeth II. (Later, Kapila travelled with René to negotiate the country’s independence from Britain.) In Somaliland, he took up the case of army officers who were charged with orchestrating a coup.

There was a cheeky, contrarian side to him, Sheetal told me. One of the clients he delighted in representing was a globetrotting numismatist who was often apprehended with foreign currency. “He’d come out of prison and call my father,” Sheetal said, “When asked if he’d finally learnt his lesson, he would say, ‘Achhroo, just one more deal and I’ll settle down.’”

Njonjo, Forex, Prison

y the mid-1970s, Charles Njonjo had become a key power centre in the Kenyan establishment, and the standard-bearer for Africanisation. Tom Mboya had been murdered in 1969. Jomo Kenyatta, in these years, had become increasingly “distant” and “erratic” and some of his powerful associates used the judicial system to settle scores with opponents. [11]

Kapila remained one of the few lawyers who challenged the government on civil rights. Politicians still sought his advice when they got into trouble. “Not being a politician assured him safety from a killing,” Sheetal told me, “but not from incarceration.” [12]

Trouble came home—literally—in February 1977, when the police landed up at the Kapila residence. An amount of 26 British shillings and 15 American dollars was found in a suit of Kapila’s, and he was arrested for violating the exchange control rules. Soon after, an incriminatory cheque was added to the charges: a post-dated cheque issued by the Iranian charge d’affaires, Kapila’s neighbour, who had run up a bill at the Nairobi casino and wanted Kapila to settle matters discreetly.

To Sheetal, the subsequent trial was proof of how far cronyism had crept into the judiciary. Kapila, with Nowrojee as his junior, defended himself doggedly. He believed that the judgement against him had been drawn up even before charges had been framed. The judge Preet Singh Brar sentenced Kapila to 18 months in prison. Sheetal also believed that Brar was a puppet in the hands of Njonjo and of Sharad Rao, the prosecuting lawyer, who’d ingratiated himself with Njonjo by bringing him stories of how Kapila had openly mocked him.

When Nowrojee went to visit Kapila in prison, his senior remarked on how he had become a victim of the same system he had fought for so long. Nowrojee told me about the letters he wrote his sister, Kanta, then in Delhi. The tone of those was stoic, philosophical and detached. They contained notes and observations on his ordeal, but they read as if he was objectively remarking on someone else’s life. Despite this, Sheetal said, his father’s time in jail had brought on considerable stress and fatigue. On 3 October 1977, on a fresh appeal, the court reduced his jail term to two months on health grounds and imposed a fine.

His rivals were not yet done, and attempted to suspend his licence to practise law. Kapila had to leave the country in notionally voluntary fashion. He went to Oxford University to study and write. But he was back in a year. In 1984, Kenyatta’s successor, Daniel arap Moi, set up a judicial inquiry against his own bête noire for abuse of power and corruption. The nemesis in question was Charles Njonjo. Kapila, now assisted by Sheetal and the Crime Investigation Department, amassed reams of incriminating material. The charges were upheld, and Njonjo left the government in humiliation.

Music, Morals, Life

he plane was not his only indulgence. Kapila had a lifelong affair with Hindustani classical music and Urdu poetry. In a magazine piece in 2004, his son Ishan described watching his enraptured father at recitals: head bowed, eyes closed, his hands weaving imagined patterns in the air. He made frequent visits to India to attend concerts, and heard singers such as Begum Akhtar, Sheila Dhar and Ram Narain. [13]

At the music store owned by his wife’s family, Kapila once encountered Ustad Vilayat Khan. The sitarist would often be a guest at the Kapila home. Sheetal told me about some early mornings when Khan would walk unannounced into his hosts’ bedroom to share a raag-based composition that had just inspired him. Kapila also took sitar lessons from Ustad Basharat Hussain Khan of the Lucknow gharana.

By the close of the century, he had become a sort of grand old man of the law in Kenya. In 1998, when he was honoured by the nation’s Law Society, he self-deprecatingly described himself as “a remnant of an archaeological age.”

His moral compass was fashioned from the ideals of the Indian freedom struggle, particularly Gandhian non-violence, and from the values of the Arya Samaj, which had attempted to liberalise Hinduism in the nineteenth century. In the crucible of the twenty-first century, those ideals are undergoing some of their most severe tests. But in Achhroo Ram Kapila’s century, they represented standards of tolerance, and ways to understand the decisions that people made in changing and conflicted times. They served Kapila well in his career and his life.

In 2003, Kapila was made senior counsel by the Law Society, a rare honour for a lawyer in Kenya. He died that same year, aged 77, having lived and made a name for himself through times when sweeping change occurred in the blink of an eye, and where loyalties were like shifting sands. Yet, he remained true to himself, his family and his work, even when the times made it challenging. For Kapila, courage was both “physical and moral,” defined by the choices one made when confronted with a difficult situation. He told the filmmaker Donald McWilliams that he thought of a crisis as a great advantage. “You discover truths around you which you take for granted,” he said, “and there is a kind of spring cleaning in your life.”

Anuradha Kumar's nonfiction pieces have appeared in Scroll.in, thejuggernaut.com, The India Forum, and other places. She lives in New Jersey, and has degrees in history, management and creative writing. This is her second piece for Fifty Two.