Half a decade before Wuhan became ground zero of a deadly global pandemic, it was the site of Indian basketball’s greatest miracle. On a warm, sticky evening in 2014 at the Wuhan Gymnasium, the men’s team faced hosts China in the FIBA Asia Cup. [1] Despite missing some key players, China were among the tournament favourites. It wasn’t the same for India, who had never defeated their neighbours in a major international.

But the few thousand home fans in the arena were in for a surprise. As the clock ticked towards the close, their vuvuzelas and balloon clappers fell silent. In the hush, each squeak of a sole on the wooden floor reverberated across the gymnasium.

The decisive moment came with four minutes to go, as India held a 55-52 lead. India’s Amjyot Singh Gill—six-foot-eight—escaped his defender to find himself with space under the rim. He had one eye on the opponents behind him, and the other on his teammate Vishesh Bhriguvanshi.

The next instant, in what seemed like a single smooth movement, Gill caught Bhriguvanshi’s pass mid-air and slammed it into the basket, completing the spectacular ‘alley-oop’ dunk. The Indian bench erupted in cheers, throwing towels in the air. China never recovered.

An American coach, Scott Flemming, had masterminded the ‘Wonder of Wuhan’. But Gill, who top-scored in the win, and several other players on the roster, had learnt the fundamentals of basketball from a homegrown legend. Unfortunately, Dr. Sankaran Subramanian of the Ludhiana Basketball Academy was not around to see the day.

A slight Tamilian man whose Punjabi apprentices towered over him, Subramanian only spent a brief period of time as India’s national coach and never won prestigious honours like the Dronacharya award. But he had an outsize influence on the history of Indian basketball, dedicating much of his life to the development of the game. To his players, Subramanian was coach, warden, even a parent away from home. For decades, he cherished one dream: to see his sport succeed in India, and for the country to have its own full-fledged professional league.

This is the story of what happened to Indian basketball, and what Subramanian made of it.

ubramanian was born in 1938 in a village called Pirancheri in Tamil Nadu’s Tirunelveli district. He played basketball in school and college, and then went on to join the Air Force in the late 1950s. After that, he moved into coaching, first with the Air Force and the Services Sports Control Board and then with the National Institute of Sports (NIS) in Patiala.

After a brief stint as one of the coaches of the national team, Subramanian moved to Leipzig in Germany to pursue his doctorate in anthropometry, the scientific study of the measurements and proportions of the human body. For his doctoral research, he analysed hockey players in Germany and developed a method to extrapolate a player’s height and potential from the ages of 10-16.

These scouting methods came in handy when he returned to India. While height isn’t the whole story in basketball, it is a crucial factor, especially to protect the basket from the opponent’s scoring attempts. As Gill’s alley-oop in Wuhan showed, it also comes in handy during spectacular offensive plays.

“We wanted to find new talent. Our theme was ‘Tall and Talented Players.’”

The average Indian, however, is likely to be shorter than a global counterpart. (A recent paper based on National Family and Health Survey data concluded an alarming decline in the height of Indian adults, citing food intake, standard of living, and healthcare as possible reasons.) But in the villages of north-western India, men and women turn out to be taller than the national average. It is one of the reasons Punjab is the nursery of Indian basketball, and Ludhiana Basketball Academy, housed in the Guru Nanak Stadium, [2] is its centre of gravity.

A player practising his shooting on the indoor court of the LBA. Picture Credit: Karan Madhok

Decades of history connect basketball with Punjab’s largest city. In 1951, Ludhiana hosted India’s first ever basketball nationals. At the time, Teja Singh Dhaliwal was a young boy growing up in Duley, a village about 17km southwest of Ludhiana. He hadn’t watched the tournament himself, but he still recollected stories of its most memorable matches.

From an early age, Dhaliwal knew his future lay in basketball. “I was not a top-class star,” he told me about his playing days. “But I wanted to do something for the game which I could not achieve.” In the 1960s, he got involved in basketball administration. In 1991, he was appointed secretary-general of the Punjab Basketball Association (PBA).

His efforts bore fruit. Through to the late 1990s, players from Punjab formed the backbone of national team squads. But Dhaliwal was unsatisfied with how the sport was developing on ground. “We wanted specialised training, not just average results,” he explained. “We wanted to find new talent. Our theme was ‘Tall and Talented Players.’”

Meanwhile, after more than a decade at NIS Patiala, Subramanian returned to his home state at the other end of the country: Tamil Nadu. He dreamt of starting an academy there. Tamil Nadu also happened to be a powerhouse of domestic basketball, having won two men’s national titles earlier in the decade. But the Tamil Nadu Basketball Association, unenthusiastic at the time, asked Subramanian to coach in schools instead.

Slighted, he decided to return to Punjab.

The rest is history. In 2002, Subramanian joined forces with Dhaliwal and PBA president R.S. Gill to launch the Ludhiana Basketball Academy. Ludhiana was the perfect choice, an urban centre that connected all corners of Punjab, and home to marquee Indian businesses like Mahindra & Mahindra and Hero Cycles. (The academy found it easy to procure bicycles, kits, basketballs and other forms of sponsorship in Ludhiana.)

Here, the ‘Tall and Talented’ formula was put into practice. Led by Subramanian, the LBA recruited heavily from rural and semi-rural Punjab, focusing on the development of adolescent players. Over the next ten years, Yadwinder Singh, Jagdeep Singh Bains, T.J. Sahi, Amritpal Singh, Satnam Singh Bhamara and Amjyot Singh Gill, alongside other top internationals, all shaped their game at the LBA. [3]

ubramanian only enjoyed a brief stint as the head coach of India’s national side. That was in the early 1980s. It came on the back of a relatively successful decade for India, including a fourth-place finish at the 1975 FIBA Asian Basketball Championship in Bangkok—the country’s best-ever performance at the continental level.

In 1980, due to an accident of international geopolitics, the men’s basketball team had found itself as an unlikely participant at the Moscow Olympics. The United States had boycotted the Games to protest the Soviet Union’s invasion of Afghanistan. Many of its then allies followed suit, including four Asian countries with higher-ranked basketball teams: China, Japan, South Korea and the Philippines. Politically non-aligned India—the fifth-placed team in the 1979 FIBA Asia Championship—got its shot at glory.

India, coached by Lt. Col. Makkolath Rajan, lost all seven games in Moscow. Yet, the Olympic campaign marked a high point for basketball in the country. From that point, the trajectory has been mostly downhill. Since 1989, the men’s team has never finished higher than sixth in Asia’s top tournament. [4]

These sobering facts fog the optimism of the early 2000s, when it was thought that India could potentially follow China’s footsteps as basketball’s next goldmine. Both countries have a billion-plus citizens and were predicted to become economic superpowers at the turn of the century.

The similarities ended there. China has a rich history with the game: basketball has been one of its two national sports since 1935. [5] At the global level, they are no pushovers; at the continental level, they are positively giants. China has won 16 gold medals in the FIBA Asia Championships, more than all other winners combined. The Chinese Basketball Association, launched in 1995, has grown to become the premier pro league in Asia.

Perhaps the most famous fillip for China’s basketball came in 2002, when seven-and-a-half-footer Yao Ming was drafted into the Houston Rockets, a top franchise in America’s National Basketball Association (NBA). Yao’s superstardom in the world’s most valuable and glitzy basketball league meant that China increasingly featured in the NBA’s commercial plans, with pre-season tours, development academies and merchandising deals. The country had a seat at basketball’s global table.

ndians took in the growing influence of China with a mix of envy and inspiration. It seemed that only big names and deep pockets could give basketball the commercial push it needed to professionalise. There was some progress on that front: in 2010, Harish Sharma, the influential secretary-general and CEO of the Basketball Federation of India (BFI), managed to secure a partnership with Reliance Industries Limited and IMG, a behemoth in the sports and entertainment business.

The deal was supposed to kick off a new professional league within three to five years. In exchange, IMG-Reliance would have commercial rights to the game in the country, including most aspects of sponsorship, broadcasting and merchandising. The terms of the deal were not officially disclosed, but a former employee of the federation confirmed to me that the BFI was set to receive approximately ₹10 crore annually.

The same year, the BFI helped IMG-Reliance identify eight teenage basketball players—all 14 or under—for a scholarship programme at the IMG Academy in Florida. Among them was a teenager who’d picked up the game under the watchful eye of Subramanian in Ludhiana: Satnam Singh Bhamara. By 14, Bhamara stood at seven-foot two in his patched-up size-22 sneakers. (Ironically, his nickname was ‘Chotu.’)

The NBA, by this time, had taken note of India and its demographic potential. From the late 2000s, the league flew down prominent players for visits, kicked off grassroots programmes, paid salaries of foreign coaches and signed a new broadcast deal to improve live coverage. In 2011, it even set up an office in Mumbai.

Over the next few years, the sport enjoyed a brief ‘golden period,’ including the Wonder of Wuhan. In 2016, India defeated China again at the FIBA Asia Challenge in Tehran. They finished seventh in that tournament, their best showing at the Asian level in 27 years.

But trouble was brewing in the BFI. Harish Sharma’s death due to brain tuberculosis in 2012 had set the stage for a power struggle between two politically-backed factions. On 27 March 2015, the BFI held its Annual General Meeting (AGM) in Bengaluru to elect its new executive committee. The very next day, another group elected a different set of office-bearers at their own AGM in Pune.

The Bengaluru faction chose then Congress minister K. Govindaraj as its president. The Pune faction elected Poonam Mahajan, a Member of Parliament from the ruling Bharatiya Janata Party. Roopam Sharma, Harish Sharma’s widow, was voted in as secretary-general. Team Mahajan had control over the BFI’s central office in Delhi and the relationships with IMG-Reliance. Team Govindaraj had the blessings of outgoing BFI president R.S. Gill—co-founder of the LBA—and FIBA recognition.

By June that year, things had gotten so messy that the national sports ministry derecognised the BFI as a National Sports Federation. The implication of this was that all official basketball activities in the country would have to be halted until the issue was resolved. The two sides have been embroiled in legal wrangles ever since. IMG-Reliance’s funding, too, has since been paused.

It may be tempting to write this off as some inherently Indian dysfunction. But in the same year that Reliance-IMG formalised their association with the BFI, they also signed a deal with the All India Football Federation for the Indian Super League, an annual franchise-based professional football competition. That league is now in its eighth season.

Through many of these developments, until the summer of 2013, Subramanian continued to put players through the paces at the LBA. In January that year, less than a month after taking up the head coach job, Scott Flemming made a trip to Ludhiana to watch the nationals, where he picked up bhangra moves from Punjab’s state team, and met Subramanian.

“I was so impressed by him,” Flemming told me. “He was instrumental in making the Ludhiana Academy what it is today. There are many very good players all over India, but Punjab has been the standard.”

ndia’s most visible NBA connection is not with an athlete, but with a businessman. It started in 2013, when Mumbai-born software tycoon Vivek Ranadivé became the majority owner of the team Sacramento Kings. Six years later, Ranadivé was instrumental in bringing the NBA’s preseason matches to India: his Kings took on the Indiana Pacers in a pair of sold-out games at the Worli Dome in Mumbai.

The ‘India Games’ were meant to showcase the opulent and high-stakes world of the NBA. (The league’s top players earn an average of $8 million a year.) Canadian rapper Drake lent Air Drake, his $185 million custom plane, to the Kings for their flight to India. Billboards announcing the event loomed over major intersections across Mumbai. Stars from the Hindi film industry, like Priyanka Chopra and Farhan Akhtar, were spotted court-side.

To those involved with the sport in India, the event provided an up-close view of an alternate reality. In stark contrast, even the best players in India don’t receive a regular salary from the federation—or elsewhere—for playing basketball. Instead, they rely on public sector employment under the sports quota, or short-term leagues like the 3BL and the now-defunct United Basketball Alliance.

In 2017, I saw then cricket captain Virat Kohli get mobbed by fans at the Delhi airport while traveling with his Indian Premier League team. It was hard not to contrast this to the time, just months earlier, when I’d shared a three-tier train coach with the captain of the men’s national basketball team, Vishesh Bhriguvanshi, who went unrecognised and anonymous on an overnight trip to Dehradun. At six-foot five, Bhriguvanshi had to negotiate with fellow passengers for the lower berth so he could stretch out his long legs.

Basketball hardly even figures in the battle for what some journalists often refer to as the Anything But Cricket, or ABC, category. That race for eyeballs and corporate funding is playing out between sports like badminton, football, kabaddi, hockey and wrestling, all of which have or have had a pro league system in place. This has disproportionately put the onus on the success of individual basketball players, who have provided a glimmer of hope over the years. The most famous of these is Satnam Singh Bhamara.

n the summer of the year that the federation was splitting apart, Bhamara’s time at the IMG Academy in Florida had come to an end. He hadn’t performed well enough academically to secure a scholarship to a US college. So, the 19-year-old took an ambitious gamble: he declared his name for the 2015 NBA Draft.

That draft took place on a June evening at the Barclays Center in Brooklyn. After the top players were picked and many seats in the arena had been vacated, the NBA’s deputy commissioner Mark Tatum took the stage to announce the evening’s fifty-second pick (out of 60) by the Dallas Mavericks. With a joyous smile, Bhamara rose from his seat and walked to the stage to take Tatum’s hands into his own giant palms.

It was a watershed moment for Indian basketball. At any given point, there are only around 450 active players in the NBA: Bhamara, who had once ploughed the fields in his father’s farm in the small village of Ballo Ke, was now part of this exclusive club. In almost all his media interactions following the draft, Bhamara repeated one name: Sankaran Subramanian. In an interview with The Hindu, Bhamara said, “It was his dream to see one of his trainees play in the NBA someday. If I have reached this far, it is because of his hard work and good wishes.”

Bhamara was eventually unable to make the final leap to the highest level and play in the NBA itself. He spent his years in North America turning out for the Mavericks’ affiliate G League team, [6] and then with a team called St. John’s Edge in Canada’s pro league. [7] (In September 2021, Bhamara substituted the hardwood court for the squared circle, signing with American professional wrestling company All Elite Wrestling. In this, he followed the footsteps of a fellow Punjabi giant: Dalip Singh Rana aka The Great Khali.)

Just after Bhamara was drafted to the NBA in 2015, journalist Saurabh Duggal decided to visit the player’s old stomping grounds in Ludhiana. Duggal painted a picture of stark contrast to the world-class infrastructure that Bhamara now enjoyed abroad. He flagged a number of concerns at the LBA, including toilets without doors, non-functional air-conditioners, bathrooms without water taps, and a general sense of disrepair.

While the residential conditions have been somewhat upgraded since his report, Duggal stressed that the academy still had a long way to go. “The cycle of bringing in top players has to be continued,” he told me. “First, they just wanted to make a presence in Team India. Now their target is to aim for the NBA, to aim for America. The facilities will have to change with these expectations.” [8]

“When we get a result of one star player from that academy,” said Duggal, “the question is, ‘When is the next guy coming?’”

In 2017, a new option emerged for these ‘next guys’—funded, as it were, by the riches of the NBA. The NBA Academy India is tucked within the secluded borders of Jaypee Greens, a 450-acre township deep into Greater Noida, a couple of hours drive from the heart of Delhi. [9] Here, the NBA houses a few dozen of India’s most talented teenaged male basketballers.

“Whatever player he recruited, Subramanian figured out every weakness, every strength.”

Here, international coaches—including former national coach Flemming—closely track the players’ development, from their dribbling ability and shooting action to their fitness and diet. The players hope to ride on the NBA’s support to avail better opportunities as student-athletes abroad. Over a dozen young men and women from the NBA Academy or its affiliate women’s programme have already committed to play in US colleges or academies.

One standout prospect was Princepal Singh, a six-foot nine forward who became only the third Indian to play in the G League. After getting his start at the LBA, Princepal moved to the plush academy in Noida. From there, he went to the NBA Global Academy in Canberra, Australia. His move suggested that India’s top players now had a training option beyond the LBA.

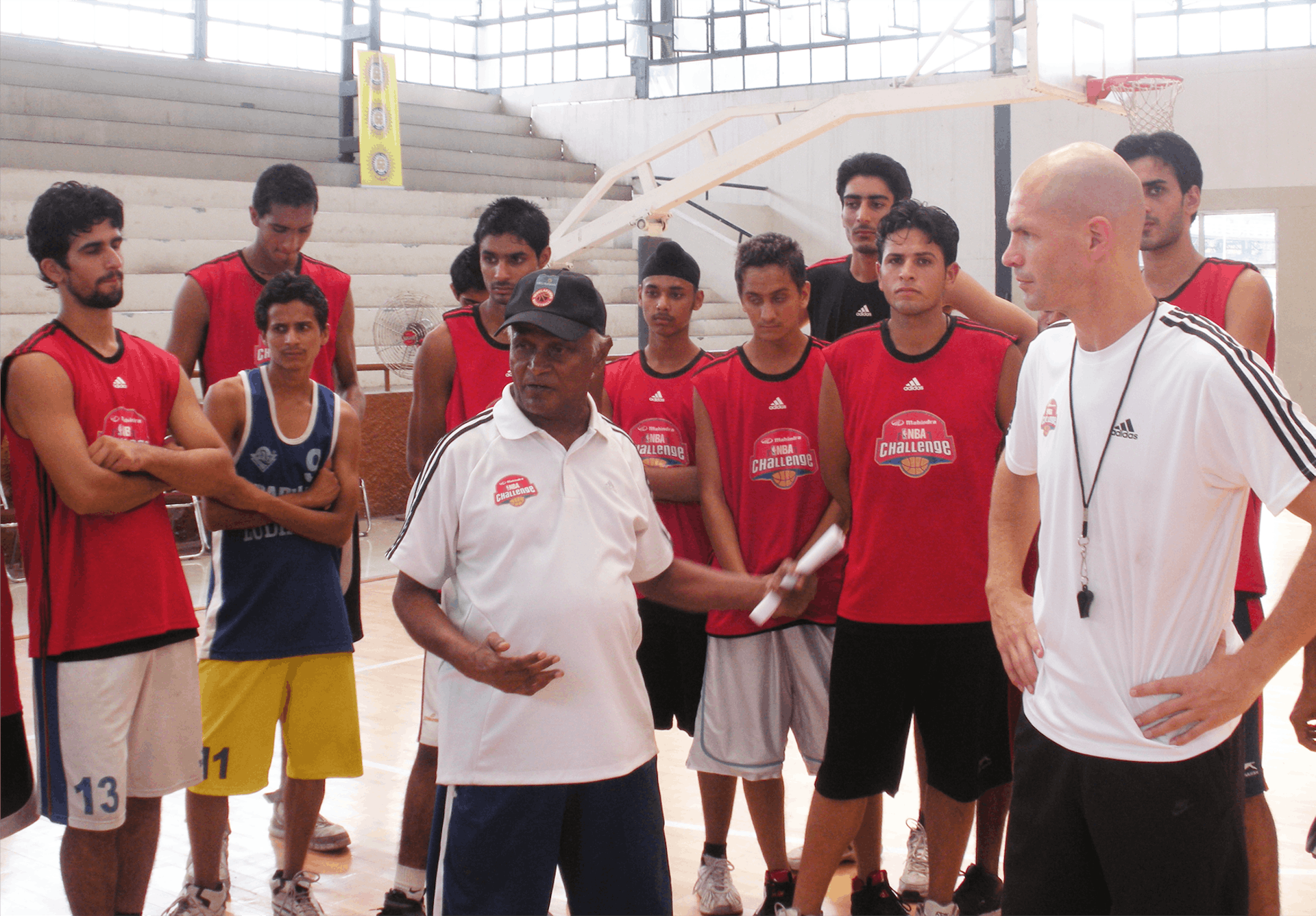

Subramanian (centre, with cap) speaking to a group of players at the LBA. Picture Credit : Karan Madhok

Without Subramanian around, things are not exactly the same in Ludhiana. “Whatever player he recruited, Subramanian figured out every weakness, every strength, everything he needed to work on,” 34-year-old Yadwinder Singh, one of the LBA’s earliest recruits, told me. “He gave them their individual attention. Now, this is not happening.”

rincepal was preceded in the G League by Amjyot Singh Gill, another Subramanian find. Gill was already enjoying an accomplished career for the national team when he was drafted into OKC Blue—NBA team Oklahoma City Thunder’s G League affiliate—in October 2017. The G League is, quite literally, a different ballgame to the NBA. The average G Leaguer earns less than one percent of an NBA counterpart. There are no private jets or luxury hotels for when players are on the road. But for a Chandigarh boy like Gill, it was an unprecedented leap forward.

In two seasons with OKC Blue, Gill played fewer than 10 minutes per game. He hardly scored a point or two in each contest. But even this limited experience made him one of India’s most successful basketballers. It was not the first time he was treading new ground: along with fellow LBA graduate Amritpal Singh, Gill had already become one of the first two Indians to play in Japan’s minor leagues. [10]

Years before any of this, however, he was one of the standout recruits at the LBA. When he was 19, Gill had earned playing time for the Punjab team at the 2011 National Games in Ranchi. In the final, he made a couple of unforced errors and was substituted out by Subramanian. “I got angry on the bench,” Gill said, “because I didn’t get my chance to shine over other players. I shouted at him; but Coach, very nicely, told me to calm down in front of everyone.”

Punjab went on to win the final handily, but Subramanian didn’t forget the moment of disrespect. “He used to get really angry at times,” Gill said. “And when we returned”—to Ludhiana—“he hit me a lot. He used to slap players if he needed to discipline us. We were like his kids.” Other players told me that even though Subramanian mostly spoke in accented Hindi, he had enough Punjabi swear words to get his point across.

In Indian sports, this sort of questionable familial relationship isn’t uncommon between gurus and shisyas—trainers and students. At the LBA, players adopted Subramanian as their parent away from home. Until his death at age 75, he was the all-round lifeline of the academy: the head coach drawing up tactical plays, the groundsman locking up the door every night, the administrator filing office paperwork.

“I used to say, ‘You're dying there all the time, in that heat, day and night, living in that small, dingy room.’”

In a loose-fitted polo t-shirt, track-pants and a baseball cap, he was a ubiquitous presence in and around the stadium. He was reserved in the presence of most outsiders but his big booming voice echoed across the halls of the indoor court when he addressed the young players.

“He was everything for the kids,” said Dhaliwal. “Sometimes he would be there for months without going back to his own family.”

Indira Bali, Subramanian’s daughter and a performance arts professor at the Punjabi University in Patiala, said she often used to ask her father what the point of it all was. “I used to say, ‘You’re dying there all the time, in that heat, day and night, living in that small, dingy room,” she told me. “All the other big sports—cricket, tennis, badminton—are all so glamourised. Where is basketball?’”

Often, Bali said, her father would pick fights with administrators on behalf of his players. “He could be very blunt,” said Bali. “He wanted transparency in selection. He wanted to run the place at an international standard, like it is in America.”

erhaps Subramanian could have had a wider influence on selection policy if he’d taken up the top job in the 2000s. But in his later years, despite his clout at the LBA and in Punjab basketball more generally, Subramanian never served as head coach of the national team.

A number of interviewees confirmed that this was Subramanian’s own decision; he refused the job despite being offered the opportunity. “He was more interested in ‘making’ players, and not in taking the credit for their success,” said Gill.

Over the years, the national team has experimented with a rotation of coaches, some Indian and some from abroad. Many of these choices have been potential ‘quick-fixes’ before a major tournament. Bali felt that her father could have been the homegrown solution. “If he did so much for Ludhiana and Punjab, imagine what he could’ve done for the national team. But he was a proud, stubborn man and wouldn’t change his mind. In 2012, so many people coaxed him to apply for the Dronacharya Award. [11] But he wouldn’t ask for it.”

Subramanian drew inspiration not from the figure of Dronacharya, but another life-coach from the Mahabharata.“ “He was fond of saying ‘Karam karo, fal ki chinta mat karo,’” said Bali. “Which is what Krishna told Arjun.” Act as you must, and don’t worry about the outcome.

Indeed, her father was an incorrigible workaholic. “Some people are happy with a nine-to-five job,” said Bali, “but he wasn’t like that. Sometimes, he would stay awake till two in the morning, watching videos, making plans.” In the pre-YouTube days, Subramanian had procured VHS tapes of basketball games and drills from around the world: Philippines, Dubai, the United States. Books on kinesiology and biomechanics shared space with tournament schedule charts on his office shelves.

Subramanian was very clear about the need for a bigger basketball nursery—not just limited to Ludhiana, but for the national level. “He wanted India to have a big professional league,” said Yadwinder. “But now, even eight years after his death, not much has happened.” [12]

ubramanian’s achievements—and his death— predated India’s social media boom. Even until a decade ago, Indian basketball news was a niche interest, known to a closed circle of participants involved with the game in some way or the other. Tales about legendary performances were only passed on by word of mouth. Local newspapers published drab box scores without any detail or analysis.

In fact, the most celebrated basketball game played in India was arguably a fictional one. In one of many basketball scenes from Kuch Kuch Hota Hai (1998), actors Shah Rukh Khan and Kajol played a full-court, one-on-one game at a children’s camp, flirting in the way of schoolyard crushes.

KKHH, and other urban college capers from India’s various film industries, have depicted basketball as the ultimate ‘cool’ sport, typically played by jocks and sneakerheads with international ambitions. In more recent times, the NBA has served basketball in India with a side of American hip-hop culture, trying to push a kind of fashionably gritty ‘street’ credential.

To promote the ‘India Games’, the league hired graffiti artists to paint walls around public places in Mumbai. For their 2019 ‘Hoop Nation’ series, they sent rapper Kaam Bhaari to the LBA to shoot a video. Social media influencers regularly promote the NBA on their platforms.

As a result, a subculture of sneakers and apparel has sprouted among India’s urban-centred basketball fan base. A promo video featuring YouTube star Bhuvan Bam and TV personality Rannvijay Singha has racked up 4.3 million views on the NBA India channel. By late 2021, the NBA even launched an India-specific fashion page on Instagram—@NBAStyle_in—and appointed Hindi movie star and fashion icon Ranveer Singh as the league’s brand ambassador in India.

The irony is that this sort of spotlight is rarely shined on India’s top basketballers. Many successful players come from less-than-humble means, and often, their best-case scenario has been the stability of government employment. Their journeys are often unpredictable and don’t fit into neat narratives.

Yet, they strive. Take Amritpal Singh, for instance. Nineteen is an age when most of the world’s top prospects are already finished products. Amritpal, at that age, had never heard of basketball. He grew up as a farmer’s son in Fattuwal near Amritsar. “In the village, I had no job,” he said, “and the only option was farming.”

But Amritpal was tall (6’10”), and that was enough. That year, his mother’s brother took him to a different village near Ludhiana, one that had a court. From there, he was taken to the LBA. “My coaches told me that if I play basketball, I could get a job,” he told me. “I was told that I had a chance to win medals, and I could even represent India.”

Over the next four years, Amritpal made rapid progress on both his game and physique. By 2014, still only 22, he was captain of the national team. After a year of playing pro in Japan with Gill, Amritpal’s career peaked when he became the first Indian to play in Australia’s top-tier league, the NBL. Now close to his thirtieth birthday, he is employed by the Punjab Police and continues to star for the national team.

“In the village, I had no job, and the only option was farming.”

Amritpal’s story is inspirational, a reminder of the ability that exists in India’s grassroots, and the work that scouts and coaches continue to do, even if in an unstructured fashion. But Amritpal’s case is also a marker of the kind of talent that India continues to let slip by. The size advantage is one of basketball’s unteachable tenets, but there are potentially skilful and athletic players all across the countryside. Many discover the game too late; most don’t discover it at all. “I meet many people who crossed their age, who were above 6’6”, 6’9”, 7-feet,” Dhaliwal said. “No one had thought about training or finding them.”

While Dhaliwal oversees the LBA’s management framework, it is head coach Rajinder Singh who now serves as the day-to-day custodian and tutor. Much like Subramanian did, Rajinder often visits small towns and villages around Punjab, looking for the next generation of prospects. “It’s common in these small towns to address the students at morning assembly, and then look over in front to see which ones are rising tall above the rest,” said Rajinder.

Rajinder admitted that some families find his pitch outlandish: to train for a sport they know little of, far away from their homes. “But the youngsters are very tech-savvy now,” he said. “They know all about the sport and are excited to come to Ludhiana. More than basketball, our promise to families is of future employability, of a way out of the farms and villages.”

In this light, the LBA’s achievements are staggering. In less than two decades of its existence, 45 of its graduates have played for the national team. “It has been a tremendous response, up to the ones that made it to the G League,” said Dhaliwal. “Honestly speaking, we’ve produced these players from slums, not luxury. But even now we’re working hand to mouth—without much support.”

Both Rajinder and Dhaliwal complained that the central government has ignored requests for equipment and facility upgrades in Ludhiana. “The tragedy of basketball in Punjab is that there is no central government help,” Dhaliwal said. “There is not a single Sports Authority of India (SAI) court in the state. I think it is discriminatory. It’s shocking. This is the state that is producing all the basketball players, but you are not helping.”

n the summer of 2013, American sportswriter Pete Thamel visited India for a story on a teenaged Bhamara and the wider basketball scene. After meeting Subramanian in Ludhiana, Thamel called him “the wise sage of Indian basketball coaches.” At the time, Subramanian had recently returned to work after recovering from a brain haemorrhage.

“I want to die on the basketball court if possible,” Subramanian said to Thamel. The story was published in Sports Illustrated on 6 May that year. Sixteen days later, as he watched his players run laps in the scorching summer heat, Subramanian collapsed on one of the outdoor courts of the LBA. The coach was rushed to the hospital. “But it was too late,” Dhaliwal said. “Only his dead body came back. It’s just like he told the American magazine.”

His daughter and her family are still hoping to immortalise Subramanian’s legacy. One of the first steps, she said, is to continue campaigning for a posthumous Dronacharya. “Being a South Indian man making a difference in Punjab, it was a big deal,” Indira Bali said. “I want the LBA to be called the Dr. Subramanian Basketball Academy.”

That would indeed be a fitting tribute. Despite its flaws, the indoor court at the Guru Nanak Stadium is a luxury for the average Indian player. It has wooden floorboards, plexiglass backboards, thick nets that make a satisfying ‘swish’ sound with every perfectly-executed basket. Posters of Amritpal, Yadwinder, Gill, and Bhamara adorn the walls around the bleachers to inspire the next generation of recruits.

The main office of the LBA is close to this court. It is officially designated to R.S. Gill in his capacity as president of the PBA. Now, Dhaliwal and Rajinder also share the same space. When he was around, this is where Subramanian, too, would spend much of his time. The wall facing the main desk has portraits of PBA presidents past, right from 1948. Behind the desk, I saw flags of the PBA and BFI flanking the centrepiece—a photograph of Dr. James Naismith, the Canadian-American physical educator who invented basketball.

It was only when I turned around, back towards the door, that I found what I’d been looking for. Dr. Sankaran Subramanian stood in a large framed photograph, wearing his trademark baseball cap and a white collared t-shirt. He looked into the camera not with a smile, but a sense of impatience. As if he’d rather be anywhere else but there. As if all that India’s greatest ever basketball coach wanted to do is get back to the court.

Karan Madhok is a writer and founder/editor of The Chakkar, an Indian arts review. His debut novel A Beautiful Decay will be published by Aleph Book Company in October 2022. You can find more of his creative work at karanmadhok.com.