I

In February 2019, a man who’d once been a soldier entered a basti in Baihata Chariali town, about an hour’s drive north of Guwahati, to serve a notice to an alleged illegal immigrant. Mohammed Sanaullah was now a sub-inspector in the Border branch of the Amingaon Superintendent’s office in Kamrup Rural district. He’d joined the Border Police after retiring from the Indian Army’s Electrical and Mechanical Engineers corps.

Now, as an inquiry officer, his main task was to identify suspected foreigners and conduct a preliminary documentation check. The task came with a sense of urgency. Sanaullah said there was pressure from Delhi—from the Union Home Minister’s office, no less—to round up ‘untraced foreigners’ from Bangladesh. 1.3 crore residents of Assam had submitted documentary proof of their citizenship to make it to the final list of the National Register of Citizens (NRC), and it was due for release in five months.

By this time, Sanaullah had spent several days trying to track down the 100-odd ‘untraced’ individuals on the list sent by the superintendent’s office. In many cases, the Gaon Burahs, village headmen, insisted that no person by the name had ever lived in the vicinity. Finally, it seemed, he ran into luck in the Baihata basti. He was at the door of a woman who had been declared ‘illegal’ by a Foreigners Tribunal several years ago.

The 35-year-old was distraught when Sanaullah told her the reason for his visit. She’d been under the impression that the case was dismissed: the tribunal lawyer had told her she’d been granted relief. She was Goria, a category of Muslims considered native to Assam. She’d fallen out with her natal family and had no support from her father in Bongaigaon; her uncle had even occupied land she owned in Jalukbari. She had a husband and young children, she pleaded.

Sanaullah’s heart went out to her, but duty compelled him. The woman was served notice to appear at the police station and advised to secure bail to avoid being detained.

“I think she was Indian only,” Sanuallah told me in November last year. “I knew what was happening was unjust, but I had to go by the order. There were spelling mistakes in her documents that she hadn’t paid attention to. Just like me.”

s Sanaullah was working through his list of untraced persons, he was living his own nightmare. A few months earlier, in July 2018, he’d discovered that he was one of 40 lakh persons whose name had been excluded from the draft list of the NRC. The reason given was that a ‘foreigner case’ had been pending against him for years. His children—two daughters and a son—had also been excluded from the list because of the case.

All this was news to Sanaullah. When he first heard about it, he put it down to nothing more than a clerical goof-up: an incorrect spelling, a mistake writing down a date. It could be nothing major for someone with 30 years of service in the Armed Forces. His papers were in place. There was a school certificate from the Assam government; tax receipts for land from before he was born. He was safe.

On 27 May 2019, just three months after his visit to Baihata basti, Sanaullah was asked to report to the Amingaon police station at 8am. It was not for a briefing about his next assignment. He was to be questioned and, later, arrested for being an illegal foreigner.

Two days afterwards he was on every news channel in Assam, being shoved into a police vehicle and to be taken to Goalpara detention centre. “This is the reward I got after serving 30 years in the Indian Army,” Sanaullah told the press in an unwavering tone. “I am heartbroken. I am an Indian, very much an Indian and will forever remain an Indian.”

In August 2019, the final version of the NRC was released. Sanaullah’s name was not on it.

II

n more ways than one, the Border Police has parallels with the Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agency, supervised by the Department of Homeland Security, in the United States. But there is a key difference. While ICE arrests, detains and deports undocumented immigrants, the Border Police surveys those presumed to be citizens because they are on voter lists. Such individuals are not undocumented.

Three other states that share a border with Bangladesh—Meghalaya, Tripura and West Bengal—have their own forces, all of which are substantially underwritten by the same scheme of the Union home ministry that funds the Border Police. But what is special about Assam is that its force is backed up by the Foreigners Tribunal apparatus. Together, they are the pillars of the legal architecture that the Union has put in place to manage the state’s unique demographic politics. The reason for their existence is rooted in one question: who is Assamese?

Assam’s history has been one of continuous migration. It has assimilated ethnic and linguistic groups from regions as varied as Kashmir, the Gangetic plains, Myanmar and China. The smelting of cultures into a singular Assamese identity has created a mosaic of entitlements and contestations. That’s why the state has historically needed arbiters, on maps, and in person.

After the British administration took over the tracts of northeastern India in 1838, they encouraged the migration of Muslims from the East Bengal delta region for agricultural reasons. In less than a century, the colonisers were pondering the demographic fall-out of their own ‘settling the frontier’ logic.

In 1931, the administrator C.S. Mullan wrote a report in which Bengali Muslims were described as an ‘invading army’ and a ‘large body of ants.’ In a passage that went on to be quoted approvingly in several official reports in independent India, Mullan prophesied that, except for Sibsagar district—the northernmost of the four districts of the Brahmaputra valley—the Assamese would not find themselves at home in Assam. The cat was set among the pigeons.

No sooner was India independent than refugees were complaining of state resistance against inclusion of their names in electoral rolls. Prime Minister Jawaharlal Nehru rebuked Assam, saying it was getting “a bad name for its narrow-minded policy.” The Assam officials’ hesitation, scholar Sanjib Baruah has written, “ran counter to the mainstream opinion in post-Partition India.”

The National Register of Citizens may have entered primetime Indian consciousness only in the last few years, but it has a long history in Assam. The first-ever NRC was ordered in 1951, in the run-up to free India’s first general election, under the charge of R.B. Vaghaiwalla, superintendent of census operations for Assam, Manipur and Tripura. Communal clashes, floods and a massive earthquake limited the scope of that exercise. Completed in 20 days, it was considered replete with irregularities.

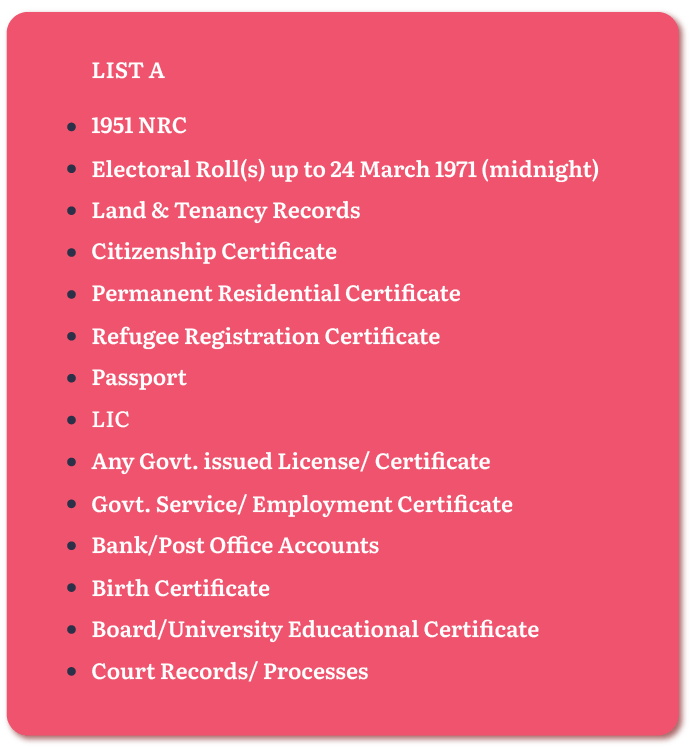

Vaghaiwalla intended this first NRC to be a ‘permanent record’ of residency, routinely updated. (Now, proof of a parent or grandparent’s citizenship in the 1951 NRC can be a crucial document in a Foreigners Tribunal case.) Then, in 1964, four of the first Foreigners Tribunals (FTs) were established by a statutory order under the auspices of the Foreigners Act, 1946. A quasi-judicial body, the FT offers a pathway to those excluded from the NRC to make their case.

The 1960s is also when the story of the Border Police, Sanaullah’s employer, begins. The Border Police was set up to detect and deport all ‘illegal foreigners.’ Between 1961 and 1966, they detected more than 215,794 such persons, and deportation notices were served or prosecution was started against 215,355 people. (Of these, a 2012 white paper prepared by Assam’s home department claimed, an estimated 40,000 persons never left India.)

Meanwhile, civil war was brewing south of the border. In East Pakistan, Bengali-speaking Muslims were asserting their linguistic and cultural distinctiveness, defying their systemic oppression by an Urdu-speaking political elite based in West Pakistan. As the civil war gained steam, the Indian states bordering East Pakistan received waves of refugees from Dhaka, Mymensingh, Sylhet and the Chittagong Hill Tracts. In Assam, migrants came to the lower part of the Brahmaputra and Barak valleys and the Lushai Hills. [1] The Border Police swung into action.

In 1979, IPS officer Hiranya Kumar Bhattacharya, the first deputy inspector general of police (DIG) of the Border branch, detected 47,658 “illegal migrants” in the voter list of Mangaldoi constituency. [2] The news caused an uproar amongst indigenous Assamese, legitimising their worst fears about the extent of unchecked migration.

Social tensions flared. A clutch of nativist organisations—led by the All Assam Students’ Union (AASU)—kicked off a civil disobedience movement against the influx of illegal immigrants. They claimed their fight was against all bidexis, foreigners, irrespective of their religion or language. Over the next few years, the groups organised civilian protests, oil and gas labour strikes, mass picketing and election boycotts.

By 1980, Bhattacharya had detected 587,000 foreigners in six Lok Sabha constituencies. In his autobiography, he wrote that Border Police officials persuaded AASU leaders to mobilise local units to file objections with the Election Commission. But the exercise did not result in any kind of substantial deportation or even voter list reorganisation. [3]

Then, on 18 February 1983, the agitation turned against the residents of Nellie town in Nagaon district. A mob of indigenous Assamese slaughtered almost 2000 Bengali-speaking Muslims, purportedly angered by their participation in the assembly elections. Now the movement that claimed to be based on jatiyotabad—Assamese regional patriotism—had taken on a communal character. [4]

The Assam Agitation lasted six long years. Finally, in 1985, the Union, state and AASU broke the stalemate by signing the Assam Accord. The Accord identified a cut-off date for citizenship: 25 March 1971, the day the Pakistani military began its crackdown on the liberation movement in East Pakistan. Later, the state government would officially confer the status of “martyrs” on the 855 people (AASU’s figure is 860) who died “in the hope of an infiltration free Assam.”

he 1971 cut-off date was not acceptable to everyone. Many Assamese nativists drew their own dividing line at the beginning of British rule in the area. The researcher Makiko Kimura, who has studied the Nellie massacre, wrote that “only the descendants of the population who started to live in Assam before the British occupation were regarded as indigenous.” Large sections of the Assam Movement agitators were, in fact, upset that the citizenship cut-off date in Assam was 1971, instead of 1950 like in the rest of the country.

My own reporting of the citizenship issue over the last couple of years suggests that the high standards of documentary proof required by FTs to establish citizenship are applied inequitably. They are not applied to caste Assamese and indigenous tribes in the manner they are to Bengali-speaking Muslims and Hindus.

The NRC rules contain a separate category called “original inhabitants”: an amorphous phrase that is informally understood to mean indigenous residents of Assam. For this category, producing documentary evidence is not essential if the registering authority is “otherwise satisfied” about eligibility. (India’s Supreme Court endorses this: in 2017, it handed down an order proclaiming the ‘tea tribes’ of Assam to be included as OIs. [5] )

Waves of migration from East Bengal in the twentieth century have, indeed, caused a significant demographic shift. At the beginning of the century, Assam’s Muslim population was 12.4 percent. At the start of the twenty-first century, it was 30.92 per cent. This rate of growth is compared with the rest of India to make a case for unchecked illegal migration from Bangladesh. That is why being a Bengali-speaking Muslim in Assam is a presumption against being an ‘original inhabitant.’

III

ost Muslims in Kalahikash village in the Boko block of Kamrup Rural district in the Brahmaputra valley trace their legacy in Assam to the colonial era. Pejoratively, they’re called ‘Miyas.’ One of them is Mohammed Sanaullah.

“I have a tax receipt from 1942 that my father paid on the land where a mosque stands today,” Sanaullah said. “It’s not like Bangladesh sent a telegram to make a receipt in Mohammad’s name.”

In Kalahikash, where vast swathes of paddy fields run along the Kulsi river, the past is remembered as a history of slights. The years between 1979 and 1985, the period of the Assam Agitation, are particularly haunting.

For the indigenous communities of Assam, those years are somewhat suffused with the nostalgia of revolution, a time when cries of ‘Joi Ai Axom’—long live Mother Assam—reverberated across the valley. But for Sanaullah and his neighbours, it was a time of madness and terror. They recalled agitating crowds of hundreds and thousands, comprising Assamese and tribal communities.

Sanaullah’s parents used to tell stories about riots that had broken out earlier, in 1951. That was the first time they heard the call that would continue to define Assamese politics for decades to come: drive away the Bengali-speakers to where they came from.

Anwar Hussain Mullah shifted from Barpeta to Boko in 1975 to become the headmaster of Champupara High School. He’d lived through police harassment in 1962 after the language agitation. [6] That was when he learnt that it was only papers that separated people like him from Bangladeshis. “It was in the middle of the day, around noon,” Mullah, who is now in his sixties, recollected. “They were going to everyone’s homes. When they came to check our papers, we showed them our NRC document, [7] the land deed, voter lists.”

Mullah told me they had seen trouble from the “opposite party,” referring to the ethnic Assamese, even in 1962. “They wanted to remove Muslims, who were seen as migrants from Pakistan back then,” Sanaullah said. “It didn’t matter what the person’s nationality really was. If he was wearing a lungi, if he was a Miya, he became a target.”

At the movement’s peak in the 1970s and early 1980s, AASU leaders like Prafulla Kumar Mahanta and Bhrigu Kumar Phukan demanded 1951 or the first NRC as the cut-off date. “But at the time, no one asked us since when we’d been living here,” Sanaullah told me. “Even we were saying that those who came after 1971 must go back. But I never saw a Bangladeshi in my village—not then, not now.”

Anwar Hussain Mullah, former headmaster of Champupara High School. Picture credit: Prakash Bhuyan.

After the carnage in Nellie, all bets were off. In the winter of that year, 1983, there were riots and arson in Champupara. Both Sanaullah and Mullah recalled the details with startling clarity. It was a Saturday, Sanaullah said, and people who’d gone to Boko for the weekly market hadn’t returned. Soon, rumours began to fly that unknown mobs had killed them.

Crowds gathered around the mosque in Champupara market. As the day wore on, a mob had gathered on the other side of the Kulsi. “Things were heating up,” Sanaullah said. “The air was thick with rumours of andolan breaking out at any moment.”

But what was andolan—revolution—for the Assamese and some of the tribes meant gondogol, trouble, for native Bengali speakers. By evening, the crowd on the opposite bank numbered over a thousand. “We didn’t know these people,” Mullah said. “We were told that they came from Boko and Chaygaon. They were armed with everything from lathis to guns.”

For the next three days, families took refuge in the premises of the Champupara High School. Outside its walls, marauding mobs burnt down homes and shops. Sanaullah alleged that he saw “Adivasis” and people associated with AASU roaming about with lathis. His family home was gutted like most in the village. Peace was restored only when the Central Reserve Police Force came along.

uslims of Bengali origin are among the most disadvantaged communities in the state. On parameters like female literacy, the community has historically lagged well behind the national average. Things have improved in the last couple of decades, largely due to lowering fertility rates and rural students pursuing higher education. This has led to the emergence of a new Miya middle-class, eager to reclaim the community’s identity through intellectual engagement and poetry.

Among the Assamese Hindu middle class, there is some wariness around the attempts to shift the Miya narrative away from the old stereotypes of char-dweller, construction labourer and rickshaw-puller. [8] Even as they agree that deportation is no longer a realistic option, leading Assamese intellectuals and writers believe that Miya assertion through poetry goes against the spirit of Assamese nationalism. [9] Earlier this year, one such writer told me that the NRC was “a futile exercise.” He didn’t want to come on record because the issue was too “emotive” for the Assamese.

Nani Gopal Mahanta, head of the political science department in Gauhati University, told me that the 1985 Accord had little relevance in 2021. He pointed to the construction labourers working in his building, all from East Bengal-origin communities. “We need them,” he said. “They’re not like the African Tutsi clan that we can subjugate”––referring to the ruling minority in Rwanda, targeted for genocide by the country’s Hutu leaders. “Who will do this house construction? Assamese tribals prefer to go and stay in Bangalore as security guards.”

Assam needed an environment that allowed the Bengali-speaking Muslims to prosper economically, Mahanta suggested. But it would also have to be one which limits their political influence to districts that have already been “taken over.” “They’re like a little brother, a new entrant,” Mahanta said. “But this new guy cannot become the head of the family.”

Mahanta’s view is arguably the relatively moderate one among caste Assamese. In Kalahikash, I’d asked Mullah what he feels about the hardliners, who view Bengali-speaking Muslims as infiltrators and sworn enemies of the jati, the community. To my surprise, he said the anger was justified.

He couldn’t blame the Assamese for holding a grudge, he said: most Bengali Muslims marry young and rear big families. “My anger is primarily at my own community for producing so many offspring without the security of a job or land.” Orthodoxy, according to him, had been the community’s greatest enemy. But there were exceptions like Sanaullah, people who went into service and educated their kids well. Such people, Mullah said, need to become the norm.

IV

he Border Police is substantially paid for by the Union. The scheme was first proposed in 1962 by B.P. Chaliha, the Congress chief minister of Assam. The Prevention of Infiltration into India of Pakistani Nationals scheme—Border Police’s formal name—was then approved by the Union home ministry. (The PIP scheme was later renamed the Prevention of Infiltration of Foreigners scheme—PIF.)

The Border Police is therefore older than the Border Security Force, which is currently India’s first line of defence on the Bangladesh and Pakistan border. Before the BSF was established in 1965, more than 1900 PIF personnel monitored infiltration from 159 watch posts, 15 patrol posts and six passport check posts. In 1987, the Union allocated 1280 additional officers to the force—806 came from Assam. [10]

Most recruits enter the Border Police through a welfare scheme for ex-servicemen run by the Kendriya Sainik Board Secretariat, which operates under the Ministry of Defence.

Brigadier (Retd) N.D. Joshi, who heads the Sainik Board in Assam, told me that ex-servicemen were a natural talent pool for recruitment in the Border Police. “Since they are already trained in combat, you don’t need to spend more than a month training them to carry out Border Police work,” he told me.

A thorough background check is carried out before retired servicemen are picked for the programme. “Our office sees their pension order,” Joshi said. “We see his service record in the form of his discharge book, which has all his details right from his date of birth, when he joined the army, his training, his postings, family details and performance during service as well as any disciplinary action taken against him.”

Ultimately, though, and likely by design, the Border Police operates in a grey area in terms of accountability. It is operationally supervised by Assam’s Home and Political Department, though I was told anecdotally by a Border Police official that 90 percent of its funding comes from Delhi.

In response to my Right to Information request about the Border Police’s funding and operations, the Union home ministry wrote that “the information does not pertain” to its office and “may be treated as NIL.” My subsequent appeal application was transferred by the ministry to the office of the Assistant Inspector General at the Assam Police headquarters. The document conveying this information noted that the ministry provided “NIL Information” to the original application “since funding of the Assam Police Border Organisation is not done by MHA.”

But Assam’s Appropriation Accounts for 2018-19 shows that a total grant of ₹ 9,544.57 lakh for ‘Checking of Bangladeshi Infiltration’ was ‘Reimbursable from Government of India.’ The Assam Police budget for the same financial year shows ₹8,719.54 lakh under ‘Checking of Bangladeshi Infiltration’ to be reimbursable.

Moreover, in March 2015, in a reply to an unstarred question raised in the Lok Sabha, then minister of state Kiren Rijiju noted that the home ministry had “sanctioned a total of 3153, including 1280 additional posts” under the PIF scheme “to assist the state government and Border Security Force….” A 2009 ‘pink book’ published by the ministry—allocating responsibilities among its divisions—assigns the PIF reimbursement function to the “Finance-IV Desk.” [11]

Assam’s Political department, on its part, responded to my RTI appeal to the Home department with partial information on the Illegal Migrants (Determination by Tribunals) Act cases and FT cases, only from December 2020. [12] For my queries on Border Police references from 2006 to 2020, ‘Doubtful Voters’ declared foreigners and my request for a copy of the police inquiry reports, they directed me to the Office of the Special Director General of Police, Border. For information on central funding, I was directed to the Home department.

A response from the Office of the Special Director General of Police, Border, said the information cannot be furnished as the Assam Police Border Organisation was exempted from the purview of the RTI. [13]

n 2005, the Border Police recruited a former sergeant named Chandramal Das under the ex-servicemen scheme. Das had served for 30 years in the Indian Air Force. In 2015, Das retired from the Assam Police after serving out his ten-year term. But while stationed with the Border branch in Boko police station in 2008, he claimed to have met a 50-year-old daily wage labourer named “Md Sanaullah.”

On 23 May 2008, Das filed a statement purportedly sworn and signed by “Md Sananullah.”

“My birth as I have heard was in Kasimpur village in Dhaka district of Bangladesh. I don’t remember the police station,” the statement reads.

“My father was also born there.”

Further, it goes on: “I don’t have any land or property in my name. My father took me along, moving from one place to another and at last, settled down in Kalahikash permanently. Perhaps, he doesn’t have any land in his own name. But we are staying in government land.” Sanaullah had never voted, the statement claimed. It was signed with a thumb impression.

The case record contains a second statement that was filed more than a year later, on 27 July 2009. In it, Sanaullah ostensibly admits that he could not produce the documents to prove his citizenship even though he committed to do so earlier. In the same statement, the signer also concedes that he was not an old resident of Kalahikash village.

On the same day, Das seems to have obtained three almost-identical witness statements from 'Md. Amzad Ali,' 'Md. Kuran Ali' and 'Md. Subahan Ali.' All three statements have this exact line: “Sanaullah, the son of Mohammad Ali, is not a permanent resident of our village. So I don’t know anything about his citizenship.”

On that July day, Sanaullah the army man happened to be in Manipur, serving in the 28 Divisional Headquarters in Leimakhong in the Kangpokpi district. His brigade was involved in the cross-border operation called Hifazat, which had been combating Naga and Manipuri insurgents since the 1980s.

When Das’s inquiry reports came into the public eye a decade later, the media began to ask questions. At this point, Das said that the man he investigated in 2008 was not the one taken to the Goalpara detention centre in May 2019.

V

mjad Ali first heard of the case when Sanaullah’s brother, Barek, confronted him in the village, demanding to know why he had reported him to the police. “I was enraged by the allegation. I asked Barek if his head was in the right place,” Amjad, who earns his living as a farmer, told me in April.

The two other witnesses had a similar reaction when they heard, on the news, that their names had been used to open a bidexi case against Sanaullah. He was a senior from school; they knew he’d joined the Central Reserve Police Force, or what most residents in the interior villages of Assam refer to as “CRP.” [14]

Kuran Ali said that he wasn’t even in the village at the time of the alleged inquiry. Back then, he was working as a Grade 4 employee in the Pollution Control Board in Guwahati. “This case is a total lie,” Kuran told me. Kinship ties bind all the four men in one way or the other. “It came as such a shock to me because Sanaullah is my sister’s son,” Kuran said. [15]

While he was working in Guwahati, Kuran said that he’d come home on the weekends to spend time with family, returning to work on Monday mornings. The day Das had allegedly recorded their witness statements was a Monday.

The three men registered separate forgery complaints in the Boko police station, but the police has made no headway in the investigation. “Apparently, Chandramal told the Investigating Officer that he wrote the statement sitting in my house,” Kuran said. “He should come and show us the part of the house where he sat and wrote this statement.”

Amjad Ali said he only found out what Das looked like when he appeared on TV channels in the summer of 2019. “Can Das identify each one of us by name in a line-up?” he asked.

It took me an hour to track down Das himself. He lived in Boko town, just a short distance from the police thana. But he refused to speak to me, making it clear that he was upset that I’d landed up at his place on a Sunday afternoon. “I don’t trust anyone. Do you understand that?” he told me in English. “The truth will soon come out.”

VI

s a soldier, Sanaullah spent much of his career in the Indian Army on field postings, including tenures in Delhi, Kashmir, Manipur, Jodhpur and Secunderabad.

On the field, given the dangers involved, he had to remain combat-ready at all times. His parent unit, the 26 Rashtriya Rifles, was often entangled in deadly encounters with Pakistan-backed militants. (He clarified that he hadn’t fought in the Kargil War, as many Indian outlets had rushed to report when he was arrested.)

For exemplary service, he’d been awarded the President’s Certificate in 2014 and been promoted to the rank of Junior Commissioned Officer. When he retired from service on Independence Day in 2017, it was as a Subedar Honorary Captain. In August 2018, he sat for the ex-servicemen entrance examination for enrolment into the Border Police. This was only a few weeks after he found himself excluded from the NRC draft.

According to a list released by the Assam Police, 721 candidates appeared for that entrance test. One candidate was not accepted on the grounds that he “could not produce original documents.” This suggests that the police did, in fact, vet documents submitted by ex-servicemen. Sanaullah had cleared the process.

At the end of August 2018, Sanaullah went to the Boko police station on NH 37 to fish out the notice which neither he nor anyone at home in Kalahikash had received. When he couldn’t find anything there, Sanaullah went to the office of the Superintendent of Police. There, he managed to get his case number. He used that to start digging through the heaps of files stored in FT No. 2 in Boko town. [16]

FT No 2 in Boko, Kamrup district. Picture credit: Prakash Bhuyan.

The result of the entrance exam was still pending when he appeared for the first hearing in the FT in September 2018. Then, he asked for some more time to produce a written statement and certified copies of his documents. His son-in-law Sahidul Islam, a Guwahati-based lawyer, appeared as his counsel. The results of the entrance exam came out in October. Sanaullah had cleared it and was required to undergo a month-long training programme at the Mandakata Police Academy. When he was at the training academy, Islam appeared in the FT to request a date for January 2019.

A training batchmate, who spoke to me on condition of anonymity, told me that Sanaullah kept to himself over the entire month they were in Mandakata. “Which was quite unlike the rest of us, who’d be exchanging our service stories or our plans for the future in a group,” the batchmate said. “Mostly, he was just lost in his world, like his mind was preoccupied with something else.”

VII

n 31 August 2019, retired Subedar Mohammed Azmal Hoque found his name missing from the final NRC list. Like his cousin Mohammed Sanaullah, he had also served in the EME corps of the Indian Army for three decades.

Two years earlier, he’d received a summons from Boko’s FT No. 2. But, unlike Sanaullah, Hoque immediately raised the issue in the local and national press. After investigating the matter, the Border Police put out a statement admitting there had been a case of “mistaken identity due to the close similarity in the names of the JCO and the suspected foreigner.” [17]

The brouhaha around the Hoque case reached the Assam chief minister as well as Army officials. In 2018, the FT member (as the judge in the tribunal is called) released Hoque from the proceedings on the grounds that he’d been “wrongly identified at the time of investigation.”

A year on, however, the NRC portal continued to show that a case was pending against him. “The FT had not given a clearance until then,” Hoque told me. “When I took the matter to Pompa Chakravarty”—the FT member who had also declared Sanaullah a foreigner—“she said my case was pending because they hadn’t been able to trace the original suspect who was reported by the Border branch.” In effect, the failure of the authorities to find the suspect continued to officially cast a shadow on Hoque’s own citizenship status.

The District Superintendent told Hoque that the matter was out of his hands even as Border Police officials assured him that his name would be included soon. Hoque then wrote to Defence Minister Rajnath Singh and General Bipin Rawat, then chief of army staff. His name finally appeared in the list later that year.

Hoque thought that Sanaullah dug himself into a hole by not speaking up about his case. “His fault is that he remained mum. He should have brought the truth out to the public much earlier,” Hoque said. “That too, he was in the Border Police. He could have raised the matter with the SP long ago.”

After Hoque won relief in the tribunal, he started volunteering with lawyer Aman Wadud. His work involved helping poor and illiterate residents in rural Assam with their foreigner cases. He told me that he offered to help his cousin, but Sanaullah didn’t want to go public because he feared he would lose his job.

The training batchmate was also surprised that Sanaullah hadn’t approached colleagues or friends from the forces. “He knew the system so well he could have nipped it in the bud. Even today, when we talked, he didn’t tell me about his case hearing in the High Court.”

Hoque put it down to the kind of man Sanaullah was: a straight arrow, but a guy who’d rather keep his head down than raise eyebrows. “I remember an incident from school. We were all protesting the appointment of an incompetent teacher for Advanced Mathematics,” Hoque said. “While we were putting pressure on the headmaster to change the appointment, he chose not to get involved. For us, it was important to speak up. Sanaullah thought, ‘Why bother.’”

VIII

he term ‘Foreigners Tribunals’ sounds weighty, but they are not, on the whole, grand settings. Located in some of Assam’s most nondescript locations, they have a ramshackle quality to them. Many of them are housed in administrative offices inside crumbling traditional houses, or in dimly-lit government buildings where the odour from the bathroom overpowers all other senses.

Four tribunals in Guwahati—officially Kamrup Metro Nos 2 to 5—are located on the ground floor of a lawyers’ residential complex. Washed laundry billows in balconies above; pressure cookers go off as suspected foreigners rehearse answers to questions about their family tree.

The public is not allowed to enter any of the FTs. I’ve only ever managed to get a peek inside a tribunal once (Kamrup Rural No. 3) on a day when the member was away attending hearings in Boko. It was on the ground floor of a telephone exchange building used by BSNL. The member’s chair was on an elevated platform, and there was a small wooden enclosure where the accused takes the stand. Apart from that, there was only enough space to accommodate the lawyers and stenographer on welded steel chairs.

Until the Union’s September 1964 order establishing tribunals under the Foreigners Act, infiltrators were being deported by the Border Police without any involvement of a judicial authority. The order, which made it mandatory for every case to be examined by a judicial authority before eviction, was put in place in the wake of pressure from civil rights organisations and adverse publicity in the international media.

According to the Assam government’s 2012 white paper, as many as 35,080 persons had been referred to the four FTs by the end of August 1965. By the late 1960s, there were nine FTs in all: Tezpur, Guwahati, two in Nowgong, Sibsagar, Goalpara, Dhubri, Barpeta and Jorhat.

Then, in 1985, 21 new Determination of Illegal Migrants Tribunals (IMDTs) were established, based on an act of the same name that had been passed by Parliament in 1983. This was in addition to the 11 existing FTs. [18] (The IMDT Act was initially applicable only to Assam, with the Union having to notify its applicability in other parts of the country.)

The law’s highlight was that it reversed the burden of proof. Unlike the Foreigners Act regime, now it would be on the State to prove that the suspect was indeed a foreigner. The legislation was meant to rein in police impunity. There would be a Screening Committee to reject frivolous complaints. A maximum of 10 private complaints could be lodged by an individual who suspected a foreigner residing in their local area.

In the late 1990s, the Asom Gana Parishad government, the political offshoot of the AASU, kicked off a campaign against the IMDT. In this, they had the support of the Bharatiya Janata Party. In November 1998, the BJP-appointed governor Lt Gen S.K. Sinha (Retd.) authored a report that stated, unequivocally, that there had been a demographic invasion of Assam by Muslims from Bangladesh.

Sinha’s report alleged vast logistical burdens caused by the new burden of proof system: “Often by the time a complaint is received or the Police initiates inquiry against a suspect, that individual shifts to another location and is not traceable,” he wrote. “When the individual is available, he insists he is an Indian national and while the Police tries to collect evidence, he often disappears.” [19]

In 2000, a former AASU president named Sarbananda Sonowal challenged the constitutionality of the IMDT Act in the Supreme Court. He won the case in 2005. A bench found the legislation unconstitutional on the grounds that it violated Article 355, which calls upon the Union to protect every state against “external aggression and internal disturbance.” Since the provisions of the IMDT Act made it virtually impossible to expel foreigners and encouraged infiltration, it amounted to “external aggression against India.” (Sonowal became chief minister of Assam in 2016, when the BJP came to power.)

The judgement effectively meant that, once again, the burden of proof fell on the defendant. The lawyer Prashant Bhushan wrote in Outlook magazine that he was yet to “come across a judgement that is so illiberal, authoritarian…uses such a fantastic interpretation of the Constitution…and shows such a lack of sensitivity to human rights and basic human values.”

Nearly 15 years later, constitutional law expert Faizan Mustafa, writing in The Indian Express, warned that the FTs, having “divorced all canons of fair trial,” had become “almost another arm of the BJP government in Assam.” Mustafa made a key observation about appointments. Earlier, the government was supposed to pick retired individuals of district or additional district judge rank. Now, even a retired civil servant “with judicial experience” or an advocate who has practised for seven years or more can be appointed as a member. [20]

Not everyone finds this questionable, especially scholars and intellectuals from Assam. Sanjib Baruah, for one, has written that the IMDT Act was unfair because it insulated illegal foreigners from India’s ordinary citizenship law. Baruah censured the private complaint provision of the IMDT Act, too, arguing that it guaranteed an illegal alien “fairly solid protection” since “the solidarities based on local and residential and ethnic networks were likely to trump the distinction between citizens and foreigners.” In other words, residents are unlikely to report people with whom they share a close ethnic kinship.

Opponents of the IMDT Act also complained that the Screening Committee was not referring enough cases to the tribunals. As per information about “detection and deportation of foreigners (illegal migrants) W.E.F 1985 to 19th July 2005,” shared by the Political department in response to my RTI, out of 414,255 inquiries referred to the Screening Committee, only 112,791 inquiries were forwarded to the new tribunals. [21]

Now, the Screening Committee, consisting of representatives of Assam’s home department and the Border Police, has a different purpose: it evaluates those FT opinions which declare a person to be Indian, and then recommends which of these decisions should be appealed in the High Court by the state government. On 20 July this year, The Assam Tribune reported that the state government had been sitting on 700 such orders that were recommended for appeal. The lack of action, the report noted, indicated a “lack of intent in resolving the illegal foreigners issue.”

IX

anaullah was cross-examined by the FT in January 2019. The public prosecutor opened by asking him when he came from Bangladesh. When he said that he’d been born and brought up in Assam, the prosecutor asked when his father had crossed the border.

A high school friend of Sanaullah’s, now deceased, came in as witness. He was asked if he knew Sanaullah’s father, to which he replied in the negative. The father passed away in 1973, when Sanaullah and his friend were six years old. How could the tribunal have expected his friend to know his father personally, Sanaullah wondered.

A second witness was the current principal of Champupara High School, who was senior to Sanaullah by a few years. The principal knew Sanaullah’s father’s name. But when he was asked if he could recognise his father, he said no.

“I was confident that I would be cleared by the FT. I had all the valid documents on me,” Sanaullah told me. Admittedly, he said, there was a series of typographic errors. “In my birth certificate, issued by the Government of Assam, my name is spelled ‘Sana’ and ‘Ullah,’ with a space in between. But I’ve always written my name as Sanaullah. This was one mistake,” he said. “My voter ID says ‘Sonaullah,’ for which I had submitted an affidavit for correction.”

His date of joining the Army had been incorrectly recorded by the stenographer at the hearing. “He made the mistake of writing 1978 instead of 1987,” Sanaullah said. “He could have asked me then and there, right? How could I have joined the Army at the age of 10? But he didn’t bring it up.”

Neither Sanaullah nor his lawyer knew about the mix-up in the joining date until they saw a copy of the order, five months after the hearing, on 25 May 2019. Islam told The Indian Express that they could have not opposed the error earlier “because Sanaullah’s signature was first taken on a blank paper on which his testimony was later printed out.” [22]

t’s now fairly well-known that the performance of tribunal members is judged on the number of foreigners they declare. When the contracts of 19 members were terminated in 2017, they challenged the decision in the Gauhati High Court. One of the grounds was that there is a conflict of interest in the Home and Political Department being involved in judicial appointments when they were the opposing party in citizenship cases.

In a June 2019 investigation, Arunabh Saikia of Scroll found that the terminated FT members declared fewer foreigners even though their case disposal rate was higher than many other members who were greenlit. That same month, Vice News published a report that was based on journalist Rohini Mohan’s RTI applications to FTs: Rohini found that data from four tribunals in a Hindu-dominated district suggested that more Muslims than non-Muslims had been declared foreigners. In April 2020, two of the members whose contracts had been terminated told The New York Times that they faced pressure to declare more Muslims as foreigners. [23]

In April this year, the Gauhati High Court passed a rare order setting aside an FT opinion that had declared the petitioner as a foreigner. In its judgement, the Court highlighted a fundamental procedural lapse that plagues FT cases: the lack of charges. All the tribunal does is inform a person, “through a mere notice or summon,” that it is alleged that they are not an Indian citizen. In such a circumstance, the defendant is “totally in the dark about what exactly they are being tried for or how they can make a case for themselves.”

In 2020, my friend and fellow journalist Anupam Chakravartty filed RTI requests with the FTs in Dhubri and Jorhat. Dhubri wrote back saying it was barred from sharing the information under the ‘contempt of court’ and ‘personal information not in public interest’ exceptions laid down in Section 8 of the RTI Act. He appealed twice against the response—the second appeal is to the Central Information Commission—but to no avail.

Earlier this year, I filed RTI requests with the FTs in Bongaigaon, Boko and Hajo, requesting to look at copies of police inquiry reports for specific periods—2004, 2008, 2015 and 2017. None of the FTs shared any documents.

X

he closest that Sanaullah got to Bangladesh was when he was taken by his former colleagues to the Goalpara jail, which houses a detention centre within its premises. Just 20km away, a purpose-built detention centre is in the works, spread over 10 acres in a rubber plantation. There’s a stream flowing nearby. Behind the 20-odd feet wall, 3000 inmates will have access to a hospital, dining area, a recreational area, six toilet blocks and a school for children. About 200 inmates will be lodged in each of the 15 four-storey structures.

The cell inside Goalpara detention centre was actually a hall, 60 feet long and 14 feet wide. It housed 50 inmates, including convicted criminals and declared foreigners. The toilet area was inside the hall—it had a single door that couldn’t be bolted. Sanaullah spent 12 nights in his cell, sleeping in a foetal position for lack of space.

He stayed there until he was granted interim bail in June 2019, which has been periodically extended. He now divides his time between Kalahikash, where he’s building a new house, and renovating his home in Satgaon, in the eastern part of Guwahati.

Since the release of the final NRC in 2019, the Border Police have not made any fresh inquiries against suspected foreigners. The status of 19.7 lakh citizens hangs in limbo as politics over the NRC continues to derail its final acceptance or rejection. [24]

The BJP was re-elected to power in Assam earlier this year. One of their more successful promises to voters was the partial re-verification of the NRC in border and interior districts. The campaign was, nonetheless, a tightrope act for the BJP.

It had to be constantly alive to the discontent unleashed by a law championed by its own central command quite recently.

In December 2019, India’s BJP-dominated Parliament passed the Citizenship Amendment Act, whose stated purpose was to simplify the citizenship path for non-Muslim minorities who arrived in India from neighbouring Muslim-majority countries—Afghanistan, Bangladesh and Pakistan—before December 2014.

In Assam, the constantly bubbling anti-bidexi sentiment boiled over when the CAA was passed. The Assamese saw it as a law that offered non-indigenous residents a new pathway to citizenship. A sea of protestors, many adorned with the traditional red and white gamusa, took to the streets, chanting Joi Aai Axom and calling for the law’s repeal. Anti-CAA protests erupted in other parts of India too. But there was a key difference: those protests saw the CAA as a nakedly anti-Muslim law.

In Assam, there was a sense of being let down by the BJP. [25] In response, the party’s gambit was to shift focus to the large number of NRC inclusions from the border districts, dominated by Muslim settlers from the Sylhet and Mymensingh districts of Bangladesh. The strategy worked. Not only did it serve to highlight the BJP’s commitment to the jatiyotabad cause, it did so while furthering its broader Hindutva agenda. Except for Akhil Gogoi—who contested the election from prison after he was arrested under the Unlawful Activities (Prevention) Act—none of the leaders at the forefront of the anti-CAA protests won an assembly seat.

Women line up at the lower primary school in Kalahikash to vote in the assembly election, earlier this year. Picture credit: Prakash Bhuyan.

Still, in Assam, the BJP continues to tread especially carefully around the CAA. “Until the government forms the rules under CAA, the rules under the Citizenship Act, 1955 are still in effect,” an official told me. Meanwhile, persons excluded from the NRC, even those with pending appeals, are being denied Aadhaar cards and passports. The fate of the 200 FTs set up to deal with appeals is up in the air. While the appointed members continued to draw a salary from September 2019 until June this year without examining a single case, 1600 support staff [26] are yet to receive their appointment letters.

A source in the government, who asked not to be named, told me that both the Border Police and the Foreigners Tribunals function according to the whims of the Union home ministry. [27] “Former chief ministers like Prafulla Mahanta and Tarun Gogoi would still stand up for the state,” he said. “But not this government.”

anaullah’s case was supposed to come up before the High Court early this May, but non-urgent matters were postponed until further notice because of the deadly second wave of the pandemic. Sanima Begum, his wife, lives in perennial fear of her husband being hauled off to a detention camp.

Sanaullah still believes that the Indian Army will come to his rescue. “Overnight, my pension and other documents used in the police verification went viral,” he told me in a conversation last year. “That wouldn’t have happened if they hadn’t supported me. Even General Rawat said they’d provide all the needful.”

A source in the Armed Forces, who asked not to be identified, said that the matter was effectively out of their hands after it reached the FT. While admitting the army relies on police verifications in its own recruitment process, [28] he maintained that it would be difficult for the army to comment on the order since the tribunal follows its own standards for documentary proof.

N.D. Joshi told me that the record office of every regiment has a copy of all the original certificates of its personnel. “There’s no question of the documents with the record offices being fake,” he said. “The recruitment office also sends the documents to universities and other issuing offices to verify their authenticity, apart from the police verification.”

When I asked Joshi whether the tribunal order undermines the verification conducted by the Indian Army, he tread carefully around the question. “Once the case is in court, we cannot get involved,” he said. “We have to keep faith in the judicial and constitutional system.”

After years of living by ‘Follow the order,’ Sanaullah now believes in satyamev jayate: truth alone triumphs. “In my case, the government got caught,” he told me. “The flaw in the system was revealed. How did the member declare that I’m a post-1971 foreigner when a school certificate issued by the Assam government says that I was born here in 1967?”

I asked him if he ever wondered how someone like him—far from an illiterate daily wage worker—became the target of such an exercise. He hesitated to answer at first. Then, he admitted, it felt like a deliberate move. The FT had sent a copy of the order to Border Police officials even before they sent one to him. It was quite clear, he said, that they didn’t want to give him a chance to apply for bail.

“Only for jatiyotabad.”

Note: The masthead image, photographed by Prakash Bhuyan and treated by Akshaya Zachariah, is of Sanaullah at his residence in Satgaon, Guwahati.

Correction: A previous version of the subhed of this story referred to Mohammed Sanaullah as an ‘engineer.’ Sanaullah was part of the engineering corps. The editors regret the error.

Makepeace Sitlhou is a Guwahati-based independent journalist covering India’s Northeast for several national and international publications. She has received several media fellowships and awards including the National Media Award, the South Asian Journalism Award and the Laadli Media Award for Gender Sensitivity.