“Hi, I’m Sanjana,” began my conversations with 47 strangers on the internet recently. Their names were, by and large, also ‘Sanjana.’

Sanjana Parag Desai’s mother had known what she was going to call her daughter for eight years. Sanjana Harikumar’s mother had known for nine. For Sanjana Prasad and Sanjana Hariharan, their elder sisters had made the decision before they were ten years old themselves. Arun Thomas, who named his daughter Sanjana in 2009, vividly recalls the first time he heard the name.

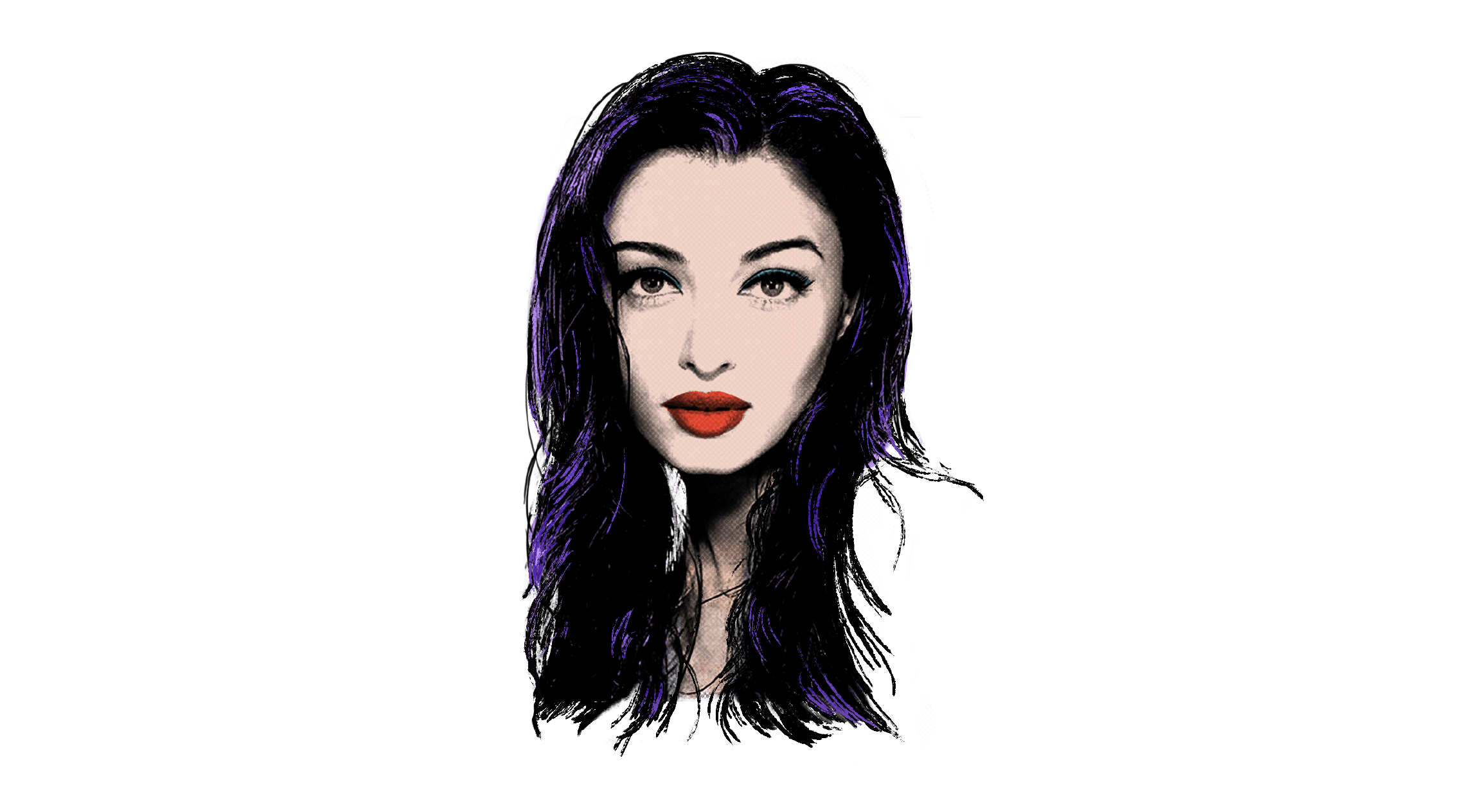

The year was 1993, and the 50-second phenomenon that had swept them up—along with the rest of the nation—was a Pepsi commercial called Yahi Hai Right Choice Baby! Starring Aamir Khan, Mahima Chaudhary (credited with her birth name Ritu) and Aishwarya Rai, the “young and popular models of the time,” as my father described them, the ad begins on a stormy evening.

A man in a brown jacket, evidently single, is humming as he plays chess with himself. The doorbell rings. It’s a beautiful young woman. She wants to know if he has a Lehar Pepsi. He’s run out, but she won’t settle for anything else. In a heartbeat, he jumps out the window and runs across the road, braving rain, traffic, and closing shop shutters, to bring her a sweating cola bottle.

Before he knows it, there’s another knock on the door. “That must be Sanju,” says the beautiful neighbour. “Sanju?!” he splutters, wondering if there’s a boyfriend in the mix—until in she comes, wearing red lipstick and wet hair.

“Hi, I’m Sanjana,” says the 19-year-old Aishwarya Rai. “Got another Pepsi?”

he first time I met another Sanjana named after a model in a soft drink commercial was in 2018. “What was my father thinking?” exclaimed Sanjana Vasudevan. “Did he think she was hot?”

It was a rhetorical question. Prahlad Kakar, the director of the ‘Sanju ad,’ as it came to be called, had very specific instructions. “I told Aishwarya: Walk in, lean against the door. Your look has to say,” said Kakar, putting on a hoarse, female voice now, “If you want me, come and get it.”

A few months ago, I wondered how many Sanjanas were like us. A clear pattern revealed itself on investigation. There were more than twice as many Sanjanas born in 1993 as in the preceding three years, according to voter rolls from the 2015 Delhi assembly elections. [1]

I put out a tweet calling for other Sanjanas, wanting to understand who was named after the ad and why. This brought forward several tales of smitten Indian families. Rai’s was the “face that launched a thousand babies,” as Kakar put it.

Yahi Hai Right Choice Baby! also launched Aishwarya Rai. A year after the release of the commercial, she made international headlines for her victory in the Miss World pageant. Her answer to the final question, about the qualities of an ideal Miss World, charmed a generation of viewers. She would have “compassion for the underprivileged, not only for the people who have status and stature,” Rai said, tall and glimmering in her white gown.

“She signified everything, didn’t she?” said my mother, about why she chose my name. “Beauty, success, making her parents proud. Plus, the name wasn’t very common then. It sounded unique and modern.” My father, an advertising professional himself, recalled of the ad: “It was on TV, day in and day out, and it was cool, youthful and lively.” (Sanjana Harikumar’s mother had similar aspirations: “She just decided she wanted her child to carry herself with the grace and poise that Ash did.”)

This Sanjana Effect, encapsulating a generation’s desire for their daughters to channel the spirit of Rai and her public success, is well-described in the 2005 book Freakonomics: “Parents, whether they realise it or not, like the sound of names that sound successful.” The authors analysed findings on how several factors—name, race, gender, socioeconomic status—are co-related with life outcomes, and posited that baby names “suggest how parents see themselves, and the expectations they have for their children.”

After their report presented that 90% of Indian surnames reveal one’s caste, the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry recommended that candidate surnames be hidden throughout the UPSC examination process.

In India, an analysis of more than 100 million records of electoral rolls, CBSE results, and matrimonial sites suggested that names reveal a variety of information about an individual—including their gender, ethnicity, religion, caste, class, and “affluence-level.” The study established, for example, that a ‘Rhea Ahluwalia’ was likely more affluent than a ‘Panna Lal.’ [2]

Names are so strongly tied to identity and life circumstances that they function as a sort of shorthand within groups and societies. People subliminally judge names that correlate with lower socioeconomic backgrounds as belonging to lower achievers, while the reverse bias benefits those with ‘high-status’ names, further cementing disparate life outcomes.

This explains why, in March 2021, the Dalit Indian Chamber of Commerce and Industry recommended that candidate surnames be hidden throughout the Indian Civil Service examination process, instead of just until the written stage. [3] Their report presented that over 90 percent of Indian surnames reveal one’s caste—which may be why there’s even an app that helps you find it out, called Indian Caste Hub.

Indians often infer meaning and social standing through each other’s last names. But Indian first names are revealing of power and discrimination too. As with so much else, the seeds for this can be traced back to our earliest religious scriptures and practices.

This entrenched signalling function of Indian names has important individual and societal implications. Because names are among the first things that people learn about us, and what we learn to identify with and respond to, they form the very basis of our self-conception, especially in relation to others. Those who like their names may find it easier to fit in, while those who dislike their names can struggle with self-esteem and psychological adjustment.

The stories of everyone I spoke to for this story revealed some fundamental truths. Indian personal names reflect not only caste, class and culture hierarchies, but also the idiosyncrasies, hopes, and fears that unite us all. Zeba Noor, an Arabic baby names expert, told me about the nuances in baby-naming practices across religions. Rahee Punyashloka, a visual artist, explained how first names can be revealing of caste and class. P.R. Sundhar Raja, an astrologer, carefully demonstrated how he arrives at the perfect baby name. Diane Rai provided insights into the business of baby-naming. And, of course, the Sanjana Effect encapsulates all that parents think about while naming their children, and how names travel through pop culture, society and time.

leven days after I was born, I was named ‘Sanjana’ at my punyahavachanam, a Tamil Brahmin naming ritual that took place at my family home in Chennai. I didn’t know too many other Sanjanas growing up, but that wasn’t the experience of some of my younger namesakes. Sanjana Saxena, born in 2001, told me that “it seemed like every third girl” in her generation in Bengaluru was a Sanjana. My older namesakes, on the other hand, clearly remembered the inflection point of the commercial. Namesakes about my age recalled their parents’ self-congratulatory feelings after the ad released, whether or not they were named because of it.

My original guess about the Sanju ad was that the name was inspired by theatre actor Sanjna Kapoor. After all, the second-most popular time for ‘Sanjana’ after the early 1990s, according to the 2015 Delhi voter roll data, had been between 1986 and 1989. (Mira Nair’s Oscar-nominated film Salaam Bombay, in which Kapoor had a cameo as a Western journalist, released in 1988.)

The name had indeed been suggested by Vibha Paul Rishi, from the Pepsi marketing team, who had named her daughter Sanjana after the actor. The original names under consideration—'Vijayalakshmi' for Rai and 'Vijay' for Aamir Khan—were cast aside for no longer being "cool." Kakar also liked 'Sanjana' because it fit the brief’s requirement for a deceptive, “tomboy” nickname, which provided the twist in the film.

Many Sanjanas liked that, too. “I love the fact that ‘Sanju’ is gender-neutral,” said Sanjana Deshpande, born in 1998. “I was a big tomboy my entire childhood.” Some other Sanjanas disliked the nickname, often because of the inconvenience of sharing it with actor Sanjay Dutt. Still others, including myself, swear by ‘Sanju’ as the name we love going by the most.

Yahi Hai Right Choice Baby! was part of PepsiCo’s first campaign in India, soon after it entered the country in 1990, a year before economic liberalisation. In what was called a “historic agreement,” [4] Pepsi agreed to ‘Indianise’ itself by adding ‘Lehar,’ meaning wave in Hindi, to the brand name.

The campaign established Pepsi’s connection to its target audience in India—the youth—and was a massive win in its new, exciting chapter of international cola wars against Coca-Cola. The immediate reaction to the commercial was so overwhelming that the makers had to disconnect their phone lines. “Everyone aged 12 and above was calling to ask, ‘Who is this Sanju?’” Kakar recalled. He later adapted the ad for Pakistan, Bangladesh, and the Philippines. [5]

“With liberalisation bringing a new age of consumption in India, marketing to the youth, who are most likely to adopt new habits, was an obvious choice given Pepsi’s international positioning already,” said Santosh Desai, a former vice president of marketing at Pepsi. [6] “Globally too, while Coke was about being inclusive and always-happy, the Pepsi brand was about youth and irreverence.”

Pepsi and Kakar had picked up the pulse of a liberalising India, aspirational and outward-looking, but still comfortable with the rhythms and rhymes of the native. There was the Hinglish slogan for the campaign, the Americanisms (“You okay in there?” Mahima asks Aamir at one point), and the hot, confident girl who knows what she wants.

Advertising, unlike cinema, is not commonly a source of inspiration for baby names, Desai explained, but the Sanju ad was an exception. “At that moment, it was the first time we were seeing that kind of advertising at such a scale.” It wasn’t just about the stars and products but the ads themselves, Desai said. “We were thirsty—for advertising!”

And with the starring role of Aamir Khan, the Sanju ad had a clear cinematic connection. In 1998, a year after both Aishwarya and Mahima made their film debuts, the female lead in Pyaar Toh Hona Hi Tha was called Sanjana. Through the next decade—to the mixed feelings of many of us Sanjanas—we were fulsomely represented on screen: Kim Sharma in Mohabbatein (2000), Bipasha Basu in Raaz (2002), Kareena Kapoor in Main Prem Ki Diwani Hoon (2003), Amrita Rao in Main Hoon Na (2004), Katrina Kaif in Welcome (2007).

“I’m a very filmy person, so I take a lot of pride in the fact that there are so many Sanjanas in the movies,” said Sanjana Hariharan, born in 1993. “But ‘Sanjana, I Love You!’ irritated me so much,” said Sanjana Pai, referring to a song from Main Prem Ki Diwani Hoon. In this sentiment, she echoes Sanjana Mohan, whose parents liked the name’s filmy, “bold” connotations, though Mohan believed it didn’t quite suit her. Sanjana Chakraborty, born in 1993, told me that the “Manic Pixie Dream Girl trope” the name took on in films in the early 2000s didn’t help.

Sanjana Roda’s parents decided to change her name, originally ‘Haryali,’ after the release of Raaz. Meanwhile, Sanjana Ganguly’s parents almost named her Bipasha. Data suggests that both ‘Sanjana’ and ‘Aishwarya’ rose in popularity after 1993. This points to an interchangeability in markers of aspiration between character and actor. It was the aura—the ‘vibe’—that parents were going for.

Rea, Myra, or, say, Ivana, which is possibly of Russian or European origin,” Diane Rai told me, are some of the popular names parents are choosing in 2021. People like their “non-traditional roots and global sound.”

Rai is the editor of the parenting site BabyCenter India, a web resource for new and existing parents. [7] The trends she’d observed resonated with what an author named D.D. Sharma proposed in a 2005 book called Panorama of Indian Anthroponomy, subtitled ‘An Historical, Socio-Cultural and Linguistic Analysis of Indian Personal Names.’ Sharma argued that selecting a name outside of traditional religious and linguistic groups—and borrowing from Persio-Arabic or Indo-Aryan influences—historically signified a liberal and global attitude.

“Divinity-based names which were so popular amongst upper classes till the last century are being replaced with names that are shorter, melodious, associated with abstract concepts, or even devoid of known semantic connotations,” Sharma wrote. He does not seem to have entirely approved of the growing trend of “pan-Indian and secular” names attempting to bridge modernity and tradition. “There seems to be no limit,” he writes, “to parental idiosyncrasies and innovative impulses.”

“You’ll see Krissh instead of Krishna, Shivansh instead of Shiva. Maybe the names will reference scriptures, like Ved or Atharv, instead of gods directly.”

“It’s interesting to see how names referencing venerated gods have changed over time,” said Diane Rai. “Earlier, names would be direct references to gods, like Karthik or Shiva, but now it’s more subtle. You’ll see Krissh instead of Krishna, or Shivansh instead of Shiva. Maybe the names will reference scriptures, like Ved or Atharv, instead of gods directly.” [8]

“You even see an anglicisation in nicknames,” Santosh Desai pointed out. “You no longer hear of Bablus and Bittus; it’s all Bits and Bubbles!” Ironically, the class of Indians seeking indiscernible names are likely least in need of buttressing their identity. It is privileged folks for whom “the next rung of aspiration is westernised and globalised,” Desai believed. “Perhaps they want to settle down abroad, or to have names that can blend in anywhere.” As far back as 1997, on Rendezvous with Simi Garewal, the actor Shah Rukh Khan explained the rationale for picking his son’s name: he could be ‘Aryan’ at home, ‘Aryaan’ in Islamic countries and ‘Arien’ in other countries abroad.

The desire to blend in is not exclusive to the Indian elite, and arguably matters as much, or even more, to those outside it. One of my batchmates from IIM Calcutta told me it was common for students who wanted to hide their caste identity to drop or change their surnames to “neutral” ones, like Kumar, Singh or Chaudhary. Rahee Punyashloka, a visual artist and filmmaker, pointed out that even ostensibly straightforward aspects of a person’s name can be loaded with meaning about sociocultural standing. “In Maharashtra, which has been a hotbed for Ambedkarites and Buddhism,” Rahee said, “names like ‘Milind’ or ‘Gautam’ could indicate you belong to a certain class or caste”—chosen to revere the Ambedkarite connection to Buddhism and implicit rejection of caste Hinduism.

“There have been many attempts within our communities to twist or drop surnames altogether, like the Periyar movement,” Rahee explained. “There is one now to change area names based on castes, because village names tend to be caste-markers.” [9] Both Rahee and my classmate identified small changes to spelling and new, modernised addendums—spelling Riya as Rhea, for instance—as potential markers of a certain class of elite, typically urban, Indian.

Indeed, personal names in India have historically been discriminatory. “Names in the upper strata were taken from legendary sources and composed of more than one constituent,” D.D. Sharma observed, “whereas those from menial or lower strata were short, mono-morphic, and pejorative, like Kallu, Buddhu, Hariya…” In Tamil Nadu and Karnataka, dominant-caste names were borrowed from higher-status gods—like Shiva, Narayan, Shankara—while oppressed-caste names adopted more local, tutelary versions of deity names—like Ayappan or Murugappan. These observations are unsurprising in light of this diktat from the Manusmriti: “For the Brahmin, the name should connote auspiciousness; for a Kshatriya, strength; for a Vaishya, wealth and for a Sudra, disdain.” [10]

Over generations, changing personal names reveal shifts in socio-cultural attitudes. To D.D. Sharma, this was exemplified by ‘Ram,’ once a frequent component of Brahmin names (Ganga Ram, Tula Ram), falling out of favour after it was adopted by people from oppressed castes in the Uttaranchal region. [11] Indian sociologists historically identified this phenomenon as Sanskritisation, the practice of disadvantaged social groups seeking upward mobility by emulating dominant-group practices, only for the latter to discard those aspirational markers in favour of new signals.

But Rahee pointed out the limits of that concept in describing the path to upward social mobility. “It isn’t necessarily about appropriating ‘upper-caste-ness,’” he said, “but about obfuscating the original disadvantage, the differentiation.”

s any number of Sanjanas who were named for what their parents thought was an auspicious Sanskrit name linked to the sun can tell you—nature is a common source of inspiration for Hindu baby names. “Meanings related to blooming, dawn or the sun are often chosen,” Rai explained. “You also see ingrained gender roles play out when boys are generally given names that mean strong, valiant, or brave.” While girls do have names that connote strength and daring—such as Durga after the goddess—they are generally given names with more “soft-natured connotations like beautiful, harmonious, and gracious.”

The Indian baby-naming industry starts at home with opinionated family members, who provide their services for free. It extends to parenting brands and their portals, online baby-name finders and tools, and, for a large proportion of Indians, to professional astrologers and numerologists. Both babycenter.in and in.pampers.com—which receive millions of visits per month—get more than 90 percent of their traffic from search queries like “typical Indian names,” “Indian boy names,” and “Indian girl names.” [12] Brands marketing to prospective parents realise that helping people name their children is solving one of their biggest problems.

“It’s interesting to see how trends fluctuate,” Rai said, “but perhaps more so to see how some things are very well-cemented.” One trend that stands the test of time is names starting with ‘A.’ “They form about a third of the names in our Top 100 lists,” said Rai. She corroborated an analysis that suggested that 25 percent of girls and 20 percent of boys had names starting with A, in a sample of 80,000 schoolchildren in 976 of Delhi’s private schools. “It’s good for parents worried about roll-calling at school,” Rai said. “But A is also considered a good start for those who are not looking at initial syllables or nakshatra.”

The nakshatra is the star sign in a birth chart, determined by the moon’s position, and is the starting point of the naming process in many Hindu communities. It is a crucial ingredient for Lucky Baby Names, an astrology-based baby-naming service run by P.R. Sundhar Raja.

Raja has a keen understanding of the parental anxiety his job can resolve. “The right baby name brings success in [sic] your child’s Health, Education, and Happiness,” reads a line on the homepage of his website. You will find it underneath his title—Dr. P.R. Sundhar Raja Ph.D. (Astrology)—and above a tool called the Lucky Baby Name calculator.

After you enter your details in the ‘calculator,’ you are taken to a page with his consultation rates. Starting at ₹1,800 for name suggestions—along with lucky colours, days, and gemstones—it goes to ₹3,000 if you want career guidance, and all the way up to ₹11,000. For that last service, Raja promises to use both astrology and numerology to suggest Lucky Baby Names.

It was this transparent rate card that set him apart in a crowded market, Raja stressed on our phone call. “In astrology, like in any other profession, there are good people and bad people,” he said. “I have seen astrologers misuse calamities and medical emergencies to cheat and charge more.”

I asked him how he goes about choosing a Lucky Baby Name. “Let’s take your name, Sanjana,” Raja said. “Detach yourself from it, and close your eyes.” He continued, “It has a beautiful and elegant sound with nice vibrations, you see? Names like that, or Aaradhna and Kaira; all these are nice names.” But certain names, he said, will have a break. “Tirubhovanasundhari!” he thundered suddenly. “Now, a typical south Indian girl might be called that, but it isn’t possible for it to be pronounced properly. Vibrations will be off!”

Vibrations mean different things to different people. The practice of consulting astrologers for baby names is mostly restricted to Hindu communities. “In Muslim cultures,” Zeba Noor explained, “fortune-telling by the stars or time and place of birth is frowned upon.” Zeba worked as an Arabic baby names expert for a popular Indian parenting blog that wishes to remain unnamed.

The blog hired Zeba to serve a market they hadn’t initially considered. After receiving multiple requests from parents to provide content relevant to Islamic culture, it published some compilations, but received critical feedback. They’d never use the names suggested, Muslim parents said. That’s when Zeba’s boss, a Hindu, realised that she needed to hire someone with knowledge of Islamic naming culture and customs.

Social discrimination among Muslims on the subcontinent, based on whether or not they belonged to the Prophet’s lineage, is common. The highest division of subcontinental Muslim social order, the Ashraf class, claimed to be linked by bloodline to the Prophet. Where social mobility was restricted by birth, oppressed Muslim groups practised varying strategies to improve their standing, “including,” as the researcher Rémy Delage wrote, “some practices equivalent to ‘Sanscritisation.’”

In 1947, Muhajir communities seeking refuge in Pakistan often adopted last names such as ‘Sayyid’ and ‘Qureshi’ to claim Ashraf status for their families. While personal names among Muslims may also offer clues to status, some naming practices are common across social order, history, and region. Typically, Allah’s 99 names, the Prophet’s name or the names of those who fought for Islam—these are “timeless classics,” Zeba said. Names belonging to such figures foster solidarity amongst Muslims and the belief of a righteous life.

“I looked for such names because I wanted to raise a man who would treat women kindly.”

But the mother of one of my Muslim classmates provided anecdotal evidence of this changing, at least among urban, white collar Muslims. “I see Muhammed being used less and less with each generation,” she said. “My grandparents’ generation had it in their names; my father didn’t; now, it’s declining all the more—for obvious reasons.” Indian Muslims, in her experience, are resorting to “common, universal names” like Sahil, Sameer, Suhail, Rehaan, or, if it is a girl, Zoya or Zara. “I do not want to do this, though,” my friend’s mother said. “I would like to call my son whatever I want to, and not hide my identity.”

As part of her job with the blog, Zeba studied Qur’anic names to understand their meanings and religious associations. She said she needed to, because websites would claim any Arabic-sounding name means ‘beautiful.’ Who was going to cross-check meanings beyond a point?

“The day I felt like an expert was when my sister came out of the operation theatre and asked me what she should call her son” said Zeba. “Shehzaan was a name I loved and had in mind, but as soon as someone heard it as ‘shaitaan’”—meaning the devil—“it was dropped.”

A similar fear caused Zeba to almost change her own son’s name. Issues with health or personality are the most common reasons to change names, she explained. “My son would throw tantrums and bang his head a lot whenever he wanted something. I wondered if something was wrong, because I had been very stressed when I was pregnant with him.”

Zeba decided not to change her son’s name after consulting a religious leader. “It was taken from the Quran,” she said. The leader told her it couldn’t be wrong, especially as she had chosen it “for its meaning of kindness and compassion.”

“I looked for such names because I wanted to raise a man who would treat women kindly,” said Zeba. Her abusive husband had left her when she was pregnant, and she wanted to ensure her son wouldn’t behave similarly in the future. “Whatever the name is,” Zeba said, “is what the person becomes.”

n 2017, journalist Sohini wrote about the aura evoked by another naming trend, given the handy catch-all ‘First World Yoga Names’ by a former colleague of hers. In her widely-read essay “The Class of Kyra, Shyra, and Shanaya in Bollywood,” Sohini observed that FWYN were mainstream Bollywood’s cool new names, replacing the Nehas, Poojas, and Anjalis of the 1990s. Never longer than three syllables, floating on “coolness and lightness,” they carried an “unmistakable aspiration to be global.” Seemingly unmoored from place, community, or any kind of identity—other than class—characters with FWYN had glamorous professions and were played by actresses who “looked the part.”

“Typically Alia Bhatt or Shraddha Kapoor might have these names,” Sohini told me on a call, “but not, say, Vidya Balan or Sonakshi Sinha [13] or Bhumi Pednekar. So the names sum up aspirations in multiple ways—through not just class, but also looks.” [14]

Sohini was inspired to write about FWYN after observing that many of her Chinese classmates adopted an anglicised first name that would help them assimilate in new, global cultures. For both India and China, she thought, the anxiety to blend in had heightened around the time of liberalisation. “With the breaking up of the USSR in 1989,” observed Sohini, “there was now only one undisputed First World, the so-called international MTV-cool-culture to aspire to.”

I was keen to hear from someone with a FWYN. Shanaya Patel’s story, in more ways than one, encapsulated an India opening up to the world. In March 2000, Shanaya’s parents were at a café in Vadodara, Gujarat, when some Shania Twain tunes came on: she was also the artist who had been playing when her father saw her mother for the first time, “during their whole arranged-marriage-thing.” [15] Finally, after eight months of “baby” and “munna,” Shanaya’s parents had found a name for her.

But “to make it different,” Shanaya’s parents changed the spelling of her name slightly. “Before me, all my cousins were named from this or that religious book,” she said. “When my parents didn’t want to go down that road, the elders were all ‘How can you do this!’—but my parents fought for it. There was a small controversy in the family.” (After actor Alia Bhatt played the archetypal ‘Shanaya’ in the 2012 movie Student of the Year, “everyone picked up that song and teased me with it,” said Patel.)

Before FWYN entered mainstream Hindi films, filmmaker Farhan Akhtar had named his daughters Shakya and Akira in the years 2000 and 2007. What celebrities call their children has always had social cachet, particularly among the Indian elite. ‘Aaradhya’ was found to be amongst the most popular Indian baby names [16] after the original Sanju, Aishwarya Rai, named her daughter that in 2011. And after it was chosen by actor Akshay Kumar and actor-turned-author Twinkle Khanna for their son in 2002, ‘Aarav’ now consistently appears on BabyCenter India’s lists [17] of most popular Indian baby names. [18]

ot all of the 47 Sanjanas had the same celebrity-inspired origin story as mine. Many parents remembered the name because of the Pepsi ad, but liked it for other reasons.

Arun Thomas didn’t want to give his daughter a “typical Malayali” name. He settled on Sanjana when he realised it meant ‘in harmony.’

Sanjna Vijh from Faridabad told me her name was a portmanteau of her parents’: Sandeep and Anjana. They had known of a Vedic connection and that it meant harmony, but Vijh said she didn’t relate with either meaning. Instead, the missing ‘a’ was what was unique about her name. (Vijh’s portmanteau origin story was shared by Sanjana Saxena, Sanjna Verma, and Sanjana Kavathalkar.)

The earliest meaning of Sanjana appears to trace back to characters from the Rigveda, where ‘Sanjna’ or ‘Samjna’—also ‘Saranyu’ or ‘Sandhya’—was a goddess and the wife of Surya, the sun god. Reading about her “tragic life story” in an Amar Chitra Katha comic helped Sanjana Srikumar, born in Delhi in 1994, connect with her name. Sanjana Prakash, also born in Delhi in 1994, was christened by her grandfather, who told her the name also meant “a beautiful tendril.”

Sanjana Parag Desai was told that her name meant—what else?—“first ray of sunshine.” “But when I Googled it,” Desai said, “I found no trace of that meaning. Instead, I found ‘gentle,’ ‘patient’ or ‘creator,’ all of which I fit with more.”

My quest even led me to Sanjana Hattotuwa and Sanjana Sugathadasa, both Sri Lankan men, who told me their name is pronounced ‘Sanjan-er.’ Hattotuwa’s father came across the name in an astrology book, while Sugathadasa’s parents chose it because it meant “clear or good vision.”

The fact is that baby names reveal something fundamental about parents, even more than they do about the children. Although the factors influencing parents may be as diverse as pop culture, phonetics, caste, class, divinity, nature, gender and religion, “very often the underlying commonalities, be they of Arabic or Biblical origin, are the meanings,” Rai said. Ultimately, a name is the vehicle that carries the parents’ wishes for their child.

These aspirations and pressures are reflected in a scene from the hit 2020 web series Panchayat. Two parents in a village are arguing about what to call their newborn son. The mother likes the traditional-sounding ‘Aatmaram,’ but the father wants ‘Aarav,’ after Twinkle Khanna and Akshay Kumar’s son.

“You only tell me what sounds better,” the man demands of his wife. “Mother of Aarav? Or Mother of Aatmaram?!”

“Mother of Aatmaram!” she replies defiantly.

“Well… well… I want to be Father of Aarav!” he splutters.

“That is not going to make you Akshay Kumar.”

Before she can lash out at the village secretary in whose office this debate is unfolding, the official defends himself: “All I did was supply your husband a modern name when he asked me for it!”

Sanjana Ramachandran is a writer and marketer who has worked on brands like Tide, Ariel, The Ken and The Caravan, amongst others. An electronics and software engineer by training, she loves writing about everything business, tech, and culture. Her writings can be accessed on her website.

Corrections & Clarifications: An earlier version of the story suggested that the naming of Rai’s character was not inspired by the actor Sanjna Kapoor. The error is regretted.