On a summer evening in the mid-1980s, the primatologist Iqbal Malik got a phone call from Tughlakabad village in Southeast Delhi. “Madamji, come soon,” a desperate voice at the other end said. “They’re taking them away from the site.”

The site was the ruins of the fourteenth century fort that gives the village its name. When Malik got there, she found people moving small cages into a van. The cages contained monkeys that had been trapped with hand snares, metal devices that snapped shut when the animals made a move for bait.

Malik and the villagers tailed the van for 25 kilometres, all the way to its final destination: the headquarters of the Delhi Municipal Corporation, located in the town hall in Old Delhi. As the cages were unloaded by the roadside, the villagers noticed that the monkeys inside were immobile.

“That’s Kamal in the cage,” one pointed out to Malik. “Oh look, Kusum’s here, too.” They confronted the corporation workers. “Hum nahi jayenge yahaan se!” the villagers said: We’re not leaving. “Bandar waapas karo.” We want the monkeys back.

Malik was then in her mid-twenties, and India’s only female primatologist. She and her team were studying the behavioural traits of the free-ranging monkeys of Tughlakabad, and the villagers had been helping with the fieldwork. Over the course of the project, the humans had grown attached to many of the monkeys. They knew how Kusum carried her baby and how Krishna used his eyes to warn others of a threat.

When monkeys started disappearing suddenly, the locals were perplexed. Soon after, the family members of the missing animals began showing signs of distress. Until that summer evening when the locals spotted the van, even Malik couldn’t understand what was happening. At the municipal corporation, they banded together to fight it out.

“What do you want with these monkeys?” the corporation workers, variously amused and surprised, wanted to know. The people of Tughlakabad stood their ground. They left Old Delhi only after the monkeys’ release had been secured.

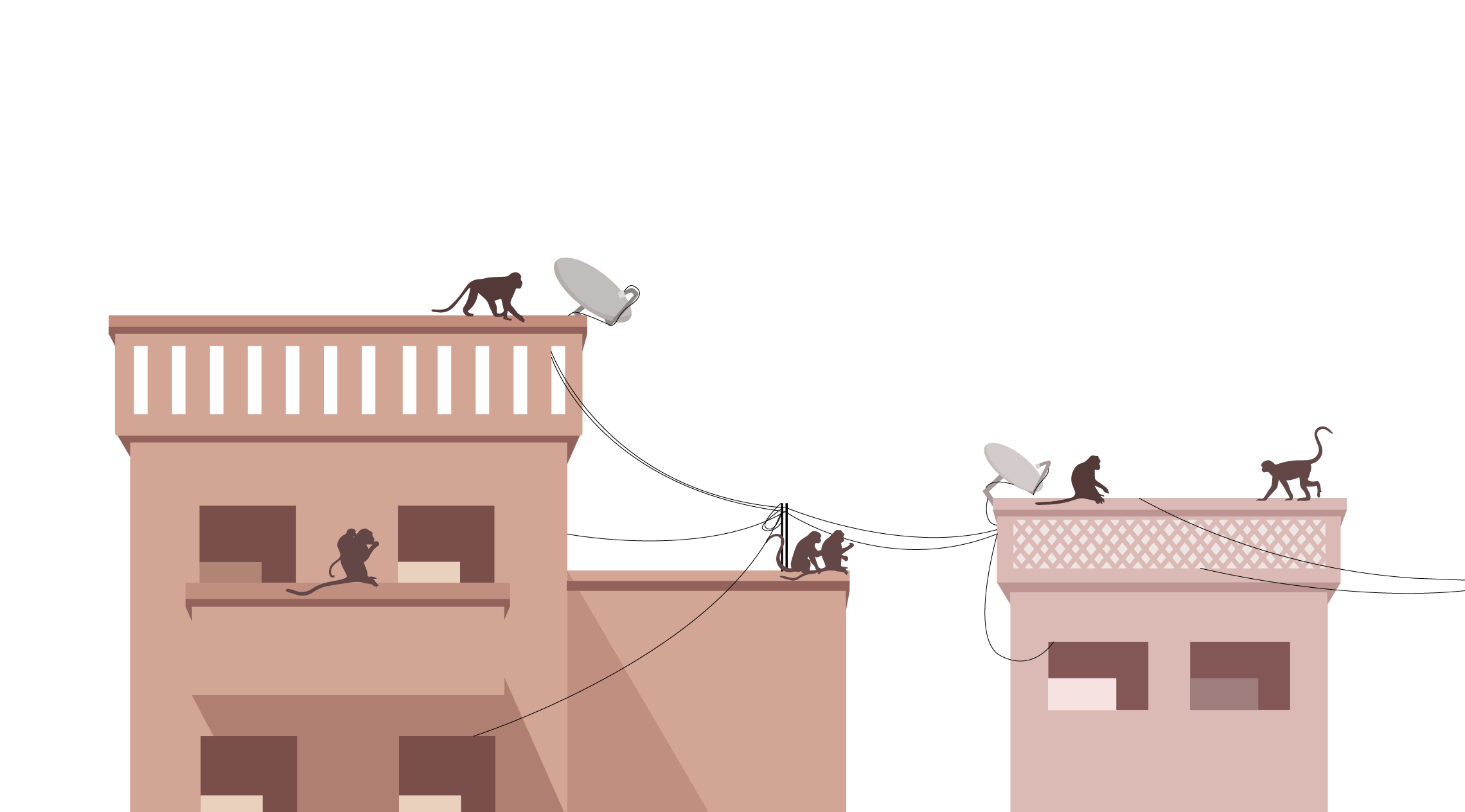

s India has urbanised over the last few decades, so have monkeys. It’s common to spot them in crowded cities now, hanging from electric wires, confidently traversing compound ledges, even entering homes in certain colonies. Monkeys haven’t just adapted to the built environment; they’ve done so by mimicking humans. This is why cases of monkey-human conflict have increased exponentially across the country. Reported numbers suggest increased incidences in various parts of India, including Himachal Pradesh, [1] Uttar Pradesh, Rajasthan, Karnataka, Tamil Nadu and the National Capital Region.

Most people will agree that the animals deserve protection. But for years, there’s been very little will to address the human motives that underlie loss of animal habitat. Civic authorities aren’t proactive about conflict management, and even their neatest solutions tend to be marked by a lack of engagement with animal behaviour, ecosystem management and human psychology.

The monkey isn’t quite as frightening or as magnificent as the leopard, another animal that finds itself at odds with humans in urban settings. But it is a beloved creature. Many devout Hindus revere it as an incarnation of Hanuman, and as a reminder of the loyal simian army from the Ramayana.

Monkeys are also a part of Delhi’s story. They belong in its landscape and its memory. The descendants of the monkeys that once roamed the forests of Raisina Hill continue to hang about the area, occasionally catching the attention of the high and mighty that rule modern India from this enclave. [2] Today, those forests endure only in a patchy arc from north to south as the Delhi Ridge. The city’s taming of the wild has had some disastrous consequences. These include psychological ones. 2021 marks two decades since the collective psyche of Delhi was gripped by the hysteria of a predator known as Kaala Bandar, the Monkey Man, whom eyewitnesses variously believed to be red-eyed, vulpine-snouted and eight feet tall.

Humans have to coexist with monkeys. But as I discovered while reporting this story, we really don’t know how to do so anymore, if we ever did. Where the issue has been headlined, as it was in Himachal Pradesh, results have been discouraging. In a last-ditch bid to assert our primacy, we’ve turned to methods of monkey population control. But sterilisation, air guns, rubber bullets, ultrasonic repellents—nothing has really worked.

I tried to find out why.

n 2007, S.S. Bajwa, then deputy mayor of Delhi and vice president of the Bharatiya Janata Party’s Delhi unit, fell from the balcony of his first-floor house after being attacked by a troop of monkeys. He later died of injuries sustained from the fall. Bajwa’s tragic death galvanised the Delhi High Court to direct the authorities to round up monkeys and move them to Asola Bhatti, a 33 sq. km wildlife sanctuary on the Delhi-Haryana border.

The Delhi government, then under the leadership of the Congress party, consulted Iqbal Malik. She advised the authorities to sterilise the monkeys before releasing them into the wild, and recommended fencing off the area with a sheet of fibreglass or jointless ply. The authorities did put up the fibreglass. To hold it together, however, they relied on a 15-foot network of iron rods and bars. Malik had predicted what would happen. Sure enough, the monkeys began to use the iron joints of the fence as a ladder to get in and out of the protected area.

Her other suggestion was that the animals be left at a site with fruit-bearing trees: imli, khair, siris, kachnar, carissa and berberis. Asola’s vegetation mix failed to keep the monkeys occupied. Seventy percent of the sanctuary is covered by vilayati kikar, an invasive species that prevents the growth of fruit-bearing trees and is particularly unsuited to the NCR’s forested areas. [3] (As of January 2018, the Delhi government was spending nearly ₹8 lakh per month to purchase 2500 kilograms of fruits and vegetables to feed the primates at Asola Bhatti.)

Both Asola Bhatti and Tughlakabad form the southern part of the Ridge area. Over the years, portions of the Ridge, once referred to as the city’s ‘green lungs,’ have been steadily replaced by hotels, hospitals, roads and public parks. “The condition of the Ridge is poor,” Pradip Krishen, environmentalist and author of a book on Delhi’s trees, explained. “It’s a place which should have 70-80 species of trees, 60-70 types of shrubs and grasses. Not even 15 percent of that exists anymore.”

This squeezing and transformation of natural habitats is why monkeys venture out into neighbouring habitats in the first place. In that mid-1980s summer when Iqbal Malik was working in Tughlakabad, she was told that the monkeys were being rounded up because of complaints from the Air Force Station near the fort, even though the station and the monkeys had coexisted for a long time before that.

“How do we begin to fix anything until we know how big the problem is?”

Then, human activity in the area intensified. A school popped up nearby, temples appeared, a water canal dried up and disappeared, the Archaeological Survey of India began excavations. Just 200 metres from the fort, the camp had everything in abundance—water coolers, waste food from the mess, trees to hang around in. The monkeys had found a new paradise.

Cut to 2021. The little that remains of the wild is not enough for the city monkeys.

Asola Bhatti simply can’t hold all the monkeys that Delhi wants to relocate. Malik said its capacity was 15,000. From 2007 to 2014, more than 18,000 monkeys were moved to Asola Bhatti. Over 1500 monkeys have been moved in the last three years, according to an official of the South Delhi Municipal Corporation (SDMC). As of 2020, a total of 25,000 monkeys have been relocated to the sanctuary.

Malik was exasperated: the authorities were simply running a transportation programme. “There is no rehabilitation element,” she said. “Too many steps are missing in between. The catching process is also harsh and unscientific.”

The common monkey or rhesus macaque is a protected species under Schedule 2 of India’s Wildlife Protection Act. Local authorities and the forest department often argue over responsibility. The SDMC official, who did not want to be named, gave me a simple explanation. The civic body is responsible only for removing monkeys on the basis of complaints, and dropping them off at Asola Bhatti. Ensuring that monkeys don’t leave the sanctuary is beyond their remit or expertise: that’s the forest department’s job.

There’s a significant casualty of this jurisdictional battle: the sterilisation process. Mohammad Akram, a monkey-catching contractor, [4] told me that, in practice, there is no veterinary process between catching monkeys and leaving them at Asola. “We take the monkeys to the corporation office,” Mohammad said. “Then, we complete some paperwork and head straight to the Asola area.” The corporation official, on his part, told me that sterilisation is the forest department’s responsibility.

This confusion, coupled with the city monkeys’ living conditions (easy availability of food; absence of natural predators; more time to procreate and care for the young), has created a perfect storm for a population explosion. Alarmingly, no reliable population data or estimates exist. “How do we begin to fix anything,” Wasim Akram, deputy director of special projects at Wildlife SOS, asked, “until we know how big the problem is?”

he problem is very big in Himachal Pradesh, particularly in tourist areas like the hill-town of Shimla, about 350 kilometres from Delhi. In July 2019, the town’s biggest hospital was reportedly seeing eight to ten cases of monkey bite daily. In 2014-15, a survey conducted by the state government found that monkeys caused an annual loss of ₹200 crore to agriculture and horticulture.

One of the major causes of the rise in human-monkey conflict in Himachal was poor ecosystem management. More specifically, it was down to the monoculture plantation of pine trees, Anita Chauhan, an assistant professor at Shoolini University in Himachal Pradesh, told me. The nuts, fruits, and flowers disappeared and were replaced by more inhospitable trees. Hungry and restless, monkeys moved out of forests.

The transformation was stark in the hills around Jakhu Mandir, a temple located on Shimla’s highest peak. Until the early 1990s, the hills around the temple were wild with forests of chestnut, deodhar and rhododendron: key pillars of the biodiversity of the Himalayan foothills. To compensate for the loss of green cover due to development projects, the HP government launched an afforestation programme in 1993. Like many governments throughout history, it chose to see a complex problem as a simple one: it simply replaced the lost trees with a monoculture of commercially viable pine.

Monkeys began to hang around in the Jakhu temple complex, lured by the easy availability of food—roasted gram or white makhana handed over by devotees, and leftovers of snacks in garbage bins. In 2004, Shimla’s municipal corporation banned the feeding of monkeys in public places except on temple premises. Authorities had to be careful not to run afoul of religious sentiments. Jakhu was particularly sensitive given a mythical connection: in the Ramayana, Hanuman is said to have rested at the site during his search for the miracle cure, the sanjeevani booti.

Chauhan was echoed by Dr. Honnavalli Kumara, one of the experts at the Salim Ali Centre for Ornithology and Natural History, Coimbatore (SACON), which operates under the aegis of the Union environment ministry. Dr. Kumara helped the wildlife wing of HP’s forest department design and conduct a monkey population survey in the summer of 2015. “The sterilisation programme was well-organised and scientific,” Kumara said. A laser operation or a human-like vasectomy or tubectomy reduced the recovery period from three weeks to three days. Monkeys could be released within a week of the operation.

“But things are not great on the ground,” Kumara said. “The monkey catchers are professional at capturing monkeys but they are not professionals at understanding the species.” In the absence of any proper monitoring or tagging system, it was difficult to ascertain which monkey was captured from which location. The monkeys also got smarter—they would disperse after being alerted to the sound of the catching truck by one of their own.

“You take a monkey away from the family and the group equilibrium falls apart.”

Animal behaviour is often a blind spot for government-run programmes. There’s a marked lack of commitment to invest in robust scientific surveys to understand group dynamics among animal populations. Monkeys, for instance, run together in collectives that are like human families. “There’s an alpha male and female, their subordinates, and babies,” Vivek Ranjan, project associate at the Wildlife Institute of India, told me. “You take a monkey away from the family and the group equilibrium falls apart. Eventually, this leads to a rise in stress levels and aggressive behaviour.”

So, despite successful sterilisation procedures, random targeting and thoughtless relocation can exacerbate the problem. That is what happened in Himachal. “Monkeys have become way more aggressive than before,” Chauhan told me. When she conducted research in the early 2000s, she came across many cases of food-snatching but not a single case of monkey bite.

In 2016, the Union environment ministry had to step in. Under an exception in the Wildlife Protection Act, it declared the rhesus macaque to be ‘vermin’ in non-forest areas in certain districts of HP. This allowed monkeys to be hunted and killed on private land, such as agricultural property. “It was understood that people would cull the monkeys as it was a nuisance for the farmers and locals,” Kumara said. But here again a complication arose. “People were not ready to kill the Hanuman form,” Kumara told me, “so they asked the forest department to take steps.”

One individual involved with the SACON study, who asked not to be named, told me that farmers have, in fact, been killing monkeys by poisoning. “That is also why there has been a sharp decline in population over the last few years,” they said. “But if you check the records, you won’t find any application to claim the prize money the government has announced. It’s simply because if they disclose killing or poisoning a monkey, they will fall off the social structure.”

Unsurprisingly, a large proportion of monkey incidents in Shimla continue to be reported from the Jakhu area. Back in Delhi, if anyone has watched and learned from the Himachal experience, they don’t have the results to show for it. “Authorities copy measures from here and there,” Kumara told me. “They don’t address the real issue.”

he Delhi Development Authority (DDA) colony in Badarpur is about seven kilometres from Tughlakabad fort. Here, 69-year-old Rajendra Singh Pawar spends his evenings in the newly-constructed park, discussing politics and post-pension life with his friends.

“That is where it happened,” Pawar said, pointing to one of the metal benches in the park. “I was sitting here when a troop of 10-15 monkeys was passing by. Some of them were carrying babies, glued to their stomachs. I was just a witness to their show.”

On that evening last summer, he’d felt a hand touch his shoulder. A monkey attacked him just as he turned. A second monkey lunged at him as he called out for help. Soon, it turned into a free-for-all. “I was crying for help, but no one came to rescue me. Everybody was scared. What could they have done?”

He freed himself after a struggle, but the monkeys left bites and scratches all over Pawar’s back. He had to be rushed to AIIMS hospital in south-central Delhi for treatment. He got a total of five injections over a period of a month. (They were free at AIIMS, but private clinics charge anywhere between ₹500 to ₹1200 per dose.)

“Even 10-15 years ago, we could see only a few monkeys here,” D.C. Dey, who’s lived in the colony for more than four decades, told me. “Now, they are everywhere at any point of time.” Earlier, Dey said, they would appear mostly in the mornings and early afternoon, never at night. “But now, there are no such timings. They are always here: sleeping on terraces, playing with rubbish bags, tearing clothes––and attacking anyone, sometimes without reason.”

Wild monkeys have adapted quickly to town and city life. Trees in urban areas can be far apart, so monkeys use poles and wires to get from one place to another. Often, this leads to electrocution. But they have learnt to live with this too, said Vivek Ranjan. “You must have seen a lot of handicapped monkeys. That’s not a coincidence. Monkeys have been known to cut off their own paralysed hands once they understand that infection can spread through the body,” Ranjan said.

When American anthropologist Dr. Daniel Allen Solomon came to India in 2007 to study monkey management in Shimla, he was taken aback by how monkeys behave around humans here. [5] For instance, Solomon explained, monkeys don’t have a natural understanding of the concept of ransom. “They learnt the concept of ransom and stealing by living among humans.”

A few decades ago, and perhaps inadvertently, the clinical research industry played a role in helping avert human-monkey conflict. Monkeys are often used in drug trials because they are close relatives of humans, sharing over 90 percent of our genetic make-up. Until 1978, India was the biggest exporter of ‘research monkeys’ to the US, sending about 20,000 of them annually at $50 each. [6]

Later that year, exports were banned for good after India found that some of the monkeys were being used in biological weapons testing. Now, pro-farmer activists in Himachal Pradesh are actually advocating to lift the ban to keep monkey populations in check. Bhaskar Ganguly, head of clinical research at a company specialising in animal care, told me that subjecting stray or street monkeys to clinical trials may not deliver the most accurate results. Trial subjects need to be nurtured and kept in tightly controlled conditions. Street monkeys, on the other hand, are exposed to several factors that may interfere with immune response to a drug or vaccine.

n March this year, I met Shahrukh, a 26-year-old monkey catcher based in Dilshad Garden in East Delhi. Shahrukh does not get a fixed salary. His bounty is tied to Delhi’s class divide. “If I catch a monkey from posh South Extension, I’m paid ₹2,400,” Shahrukh said. “But if I catch a monkey from Hindu College or Kashmiri Gate, I am paid half of that.” He mostly receives calls from Kashmiri Gate or the Delhi University North Campus area. “When we keep returning to certain areas, the monkeys start to recognise us. They are very smart. So then we wear headscarves or monkey caps.”

A young monkey catcher like Shahrukh is typically trained by a contractor like Mohammad Akram, an old hand in the business. Forty-two-year-old Mohammad grew up in the Bhalswa Dairy area, close to the Haryana border. He is from a family of madaris or animal trainers, originally from Rajasthan. “I learnt the art on a visit to Rajasthan some 25 years ago,” Mohammad told me. “We grew up with monkeys, so it was not so difficult.”

Over his long career, Mohammad has had innumerable stitches and injections as a result of monkey attacks. He told me about a specific instance about “eight to ten years ago.” The municipal corporation had sought his assistance to capture a notorious monkey that had instilled fear among the people who used the Ghanta Ghar-Tis Hazari route in North Delhi. Locals referred to the individual as khooni bandar—the bloodthirsty monkey. There was a bounty of ₹21,000 for its capture.

“If I catch a monkey from posh South Extension, I’m paid ₹2,400. But if I catch a monkey from Hindu College or Kashmiri Gate, I am paid half of that.”

Mohammad and his team reached the site and set up a bait of bananas in a cage. The monkey took its time but eventually entered the cage. Just when it was time for Mohammad to lock it, the monkey broke the cage and attacked him. “Soon there was blood everywhere. The monkey had ripped open my skin with teeth and nails. Nase bahar aa gayi thi meri,” remembered Mohammad. My veins were popping out. The monkey managed to escape.

Mohammad was rushed to the nearby Hindu Rao hospital. “For about one year, I had to go to hospital. I had to leave work and survive on loans.” He did not receive any government aid or compensation. His hands are still weak, and he can’t make as many catches as he used to earlier.

f the monkey needs to be shooed—and not caught—there are efficient ways to do it, Mohammad explained. One is to make langur noises to scare the monkey. Another is to spook the monkey with a real langur.

Mohammad has had to scrap the latter approach after he came under the radar of the forest department. “I had a langur before. But then the forest department people came, took away the langur and filed a case against me. I lost my investment of ₹5,000 for the langur and I also had to shell out money for bail.” For his langur duties, Mohammad was paid ₹15,000 a month directly by the residential societies and colonies that availed his service.

The wildlife biologist Ranjan called these methods “opportunistic capturing.” “Until a group or troop of monkeys are not studied properly in a region, it is difficult to come up with a lasting solution,” Wasim Akram of Wildlife SOS told me. A recurring theme in my conversations for this story was the idea that such a “lasting solution” should be underpinned by long-term tolerance rather than short-term empathy. “What do you think happens to monkeys in tourist places in the off-season?” asked Dr. Anish Andheria, president of the Wildlife Conservation Trust. “During the season, people go to such places with high euphoric energy. They get emotional when they spot a monkey staring at their food, and offer them a bite.”

The ordinary upper-class, urban-dwelling citizen’s view on the monkey problem often demonstrates the Not In My Back Yard or NIMBY syndrome, said Ashish Kothari, co-founder of an environmental NGO called Kalpavriksh. “People are happy conserving wildlife and forests,” he pointed out, “but not at their expense. City dwellers find it easy to revere the animal but do not want to peacefully coexist with it.”

“Monkeys can be shooed away by throwing some water, but people choose to attack them, run behind them,” Wasim said. “We receive phone calls at Wildlife SOS when people simply spot monkeys on trees and buildings. People have very low tolerance.”

Ever so often, English newspapers in India and abroad, mesmerised by the monkeys of Lutyens’ Delhi, will point out that our coexistence with monkeys is fraught, and that we should do something about it. Elite concern for human-animal relations doesn’t use words like pests, menace and vermin. But it does see animals as a threat to the human stranglehold on land, food and ecosystems. “Who is a menace for whom?” Dr. Kumara asked. Humans created monkeys’ problems.

We did the same with pigeons, who were flown out of their natural habitats, and then got cosy in our air-conditioning units, terraces and concrete tower blocks. They’re now seen as disease-causing vermin that haunt the great cities of the world, from Washington to Paris to Mumbai. But they wouldn’t have proliferated at their extraordinary rate if cities, and humans, hadn’t been so hospitable in the first place.

India has culled nilgai and wild pigs before, trying to prevent them from encroaching what humans have demarcated as their own property—but in the hinterland, reports of loss of property because of these animals is still common. There’s no silver bullet. In fact, despite its failures, the Himachal model of animal control may be as good as it gets: Kumara thinks it’s among the best out there. Thailand, Indonesia, and the Philippines, among others, are currently trying similar methods to control their monkey population.

All human settlements began in coexistence with animals, and also in competition with them. Mentions of naughty monkeys may be found in literature as far back as the Sangam era of Tamil culture. But something has changed in the last 30 years in India, with more reports of human-animal trouble than at any other point in history. While no researcher I spoke to agreed on solutions, every person, from Mohammad Akram the monkey catcher to Honnavalli Kumara the scientist, suggested that it was no good seeing this as a winnable war. If we exchanged our environmental tolerance for development, they felt, there would never be peace in our time.

Monika is an independent journalist and writes about agriculture, sustainability and the environment.