Three times last year, Netaji Subhas Chandra Bose vanished into thin air from Delhi’s India Gate. Officials blamed the wind, and the Trinamool Congress blamed the Bharatiya Janata Party. A drone show and projections lit up one end of the Central Vista for Republic Day celebrations. An empty canopy at the other end remained in the shadows.

The Times of India reported that a Bose hologram powered by a 30,000 lumens, 4KW projector, “suddenly went missing.” Sources in the Culture Ministry said that the wind knocked down the equipment meant to project the image. The light particle-packed Bose had made his appearance just a week earlier. To mark Bose’s 125th birth anniversary on 23 January, Prime Minister Narendra Modi unveiled the 28-foot high, 6-feet wide hologram with a click of a button. To the strains of the revolutionary song “Kadam Kadam Badhaye Ja,” pixels slowly arranged themselves into the familiar figure.

The hologram’s disappearance was a perfect metaphor for a prolonged national obsession. Is Bose really dead? In August 1945, the man dropped off the face of the earth. He had, in fact, died of third-degree burns following a plane crash in the Japanese colony of Formosa, now Taiwan. There is no serious doubt about the nature of his death among his family, historians, or even scholars in Taiwan.

At the time of his death, Bose was a phenomenon. The valiant but doomed military campaign of his Indian National Army in the jungles of Southeast Asia had captured India’s imagination, and independence was becoming more of a reality with every passing day. Rumours flew thick and fast once news of the plane crash began to circulate, with no accompanying notices of an autopsy or a funeral or even a photograph of his body. Some began to say that his Japanese allies had “helped Bose enter Russia.” This theory had takers, especially since Bose was well-known for slipping in and out of countries and disguises.

Some of those conspiracy theories have had a long life, and new ones were spawned in the decades to follow. In present-day India, the ruling BJP has used Bose’s memory and his demise to co-opt his legacy, though in his lifetime, Bose was firmly opposed to the BJP’s forebears and to the idea of Hindu supremacy.

In 2016, the Modi-led government oversaw the declassification of papers related to Bose’s death. But even as the prime minister unveiled the granite statue of Bose that replaced the hologram under the canopy, his government has yet to draw a line, firmly and publicly, under the fact of Bose’s death. In a political climate where misinformation spreads rapidly and widely, the death is still being reported as a “mystery” in many quarters. But there is closure to be found for those who look. I went looking for it in Taiwan, where the mystery supposedly begins but where, in fact, it ends.

A Historian in Tokyo

n March 2022, soon after Bose’s hologram went missing, I met Professor Chen Li-fu on the sidewalk outside his apartment where he lives in Taipei. He had just returned after a long commute from Aletheia University, where he teaches East Asian history and Cultural Policy. To get to Chen, I had written to a Taiwanese diplomat in Delhi, also named Chen, who had quoted him in an article about Bose’s legacy in Taiwan.

That afternoon, I followed Professor Chen into the recreation centre on the ground floor of his high-rise building, where senior citizens played ping-pong. From his backpack, he pulled out history books written in Japanese to show me. Amongst them was the historian Nobuko Nagasaki’s Indo dokuritsu: Gyakkō no naka no Chandora Bōsu, [1] a 1989 title with a picture of Bose, Mohandas Gandhi, and Jawaharlal Nehru on the cover.

“The students were instructed to fan out across the grounds to pick up the fallen jewels. Perhaps the Japanese thought the young girls were innocent and would not pocket them.”

In 1996, as a graduate student, Chen poked around dusty archives in Tokyo, researching how the imperial Japanese army used Taiwan as a base for their invasion of Southeast Asia. There, he first read about the infamous plane crash that would become the focus of three official inquiries in India. [2]

The Japanese Bomber plane had crashed within minutes of taking off from the Matsuyama Aerodrome, now called the Songshan Airport. Bose and his chief of staff Colonel Habibur Rahman were on board. (The latter survived to testify in front of a commission investigating Bose’s death in 1956.) “Bose dying in an air crash was big news in Taiwan, because he was seen as the highest commander of India in Taiwan under Japanese colonial rule,” Chen told me. “He was in the news a lot.”

Wang Jingwei, leader of the puppet government under the Japanese Empire, welcomes Subhas Chandra Bose to Nanjing, November 1943. Credit: Academia Historica

In the Tokyo archives, Chen read about a “rain of jewellery” following the crash. Rumour had it that Bose was carrying jewellery and seed money to revive the Indian National Army from his next base. “I found references in autobiographies of former Japanese Army officers and in books about the Nakano military intelligence school,” Chen said. He remembered reading about three girls’ high schools near the crash site. “The students were instructed to fan out across the grounds to pick up the fallen jewels. Perhaps the Japanese thought the young girls were innocent and would not pocket them.”

Almost a year after we met in Taipei, Chen sent me a message on Facebook with a belated realisation: “Bose’s death in Taiwan is not only an individual’s private event,” he wrote, “but the first important political event between India and Taiwan.”

Our Man in Taiwan

he thought hadn’t struck Harin Shah, the Nanking-based correspondent for the Free Press of India News Service, until some Indian friends in Shanghai mentioned it. It was August 1946, and Shah was passing through the Chinese city on his way to Formosa on a junket organised by the Kuomintang of General Chiang Kai-shek, which was just about holding on to power on the Chinese mainland. This was meant to be a routine press tour, filled with tea parties and factory visits around a well-to-do island recovering from colonialism and war.

From the window of a friend’s place in Shanghai’s Park Apartments, Shah had noticed a dilapidated structure across the road. It was the erstwhile Capitol Theatre, his friends told him. Only “two or three years ago,” they said, the theatre teemed with hundreds of Indians from all over China. They were there for a “glittering reception” for Bose, with “high-ranking Japanese officers in attendance.”

“But aren’t you going to Formosa?” someone remarked. “Surely, you will find out the truth about Bose’s death in Formosa.”

That was when Shah realised that he could be the first Indian to go looking around for details about Bose’s death in Formosa. A working holiday suddenly took the colour of a national mission. A year and 12 days after Bose’s plane crash, Shah and 25 other newspapermen from America, Russia, Britain, France, and China, landed on the island on a bright, sunny day.

“It was like any other island in the Pacific whose geographical obscurity had been dusted off only by the communiques of war news,” Shah wrote in his book Verdict from Formosa: Gallant End of Netaji, that would be published in the midst of what he described as “cruel debates” over Bose’s death. In Taiwan, he was surprised to be fielding questions about a man people knew had died. Shah was featured in the local papers, and his mission to gather facts around Bose’s death got wide publicity around the island.

Over the course of a week, Shah pieced together the facts surrounding the crash. He interviewed a range of people: workers at the Railway Hotel where Bose stayed during his Taipei visits; the nurse who was by Bose’s side till his death; a Japanese surgeon; some medical students; the Director of the Municipal Bureau of Health and Hygiene; crematorium staffers, including an old man who cremated Bose.

Like Shah, it didn’t initially strike me that Taipei had a Bose connection. I was in the city to labour through an intensive semester studying Mandarin. But one day an American friend, also a journalist, remarked that there might be a bust of Bose in a city hospital.

“Didn’t he die here?” my friend asked.

A Temple in the City

he day after I met Chen, I visited what used to be the South Gate Military Hospital, the place where Bose was treated for the severe burns he suffered in the plane crash. My companion on this excursion was Yuan Chao Yuan, a Taiwanese journalism student. To get to the hospital, we used a map that Chen had put together for us.

South Gate is now the Heping branch of Taipei City Hospital. When Netaji’s nephew Sisir Kumar Bose visited the hospital in 1965, the old military hospital was still intact. By the early 2000s, when Sisir’s son Sugata Bose visited, it had become a swanky skyscraper, like so much of Taipei. Chao Yuan and I walked around looking for some or the other memory of Bose. “I have no idea who you are asking about,” a nurse said when we asked.

Chen’s map had also marked out the Nishi Hongan-ji Temple, where Bose’s ashes were briefly kept before they were taken to the Renko-ji Temple in Tokyo. Nishi Hongan-ji was a short walk from the hospital. As we waited for the traffic lights to change, I noticed the stillness of the temple’s premises from across the road: a den of calm in a hectic city. Senior citizens practised tai chi in the gardens.

At the small on-site museum, we asked an elderly caretaker our question. “I’ve been here for 40 years,” he said, “but I’ve never heard the name Bose.”

Searching for the Searcher

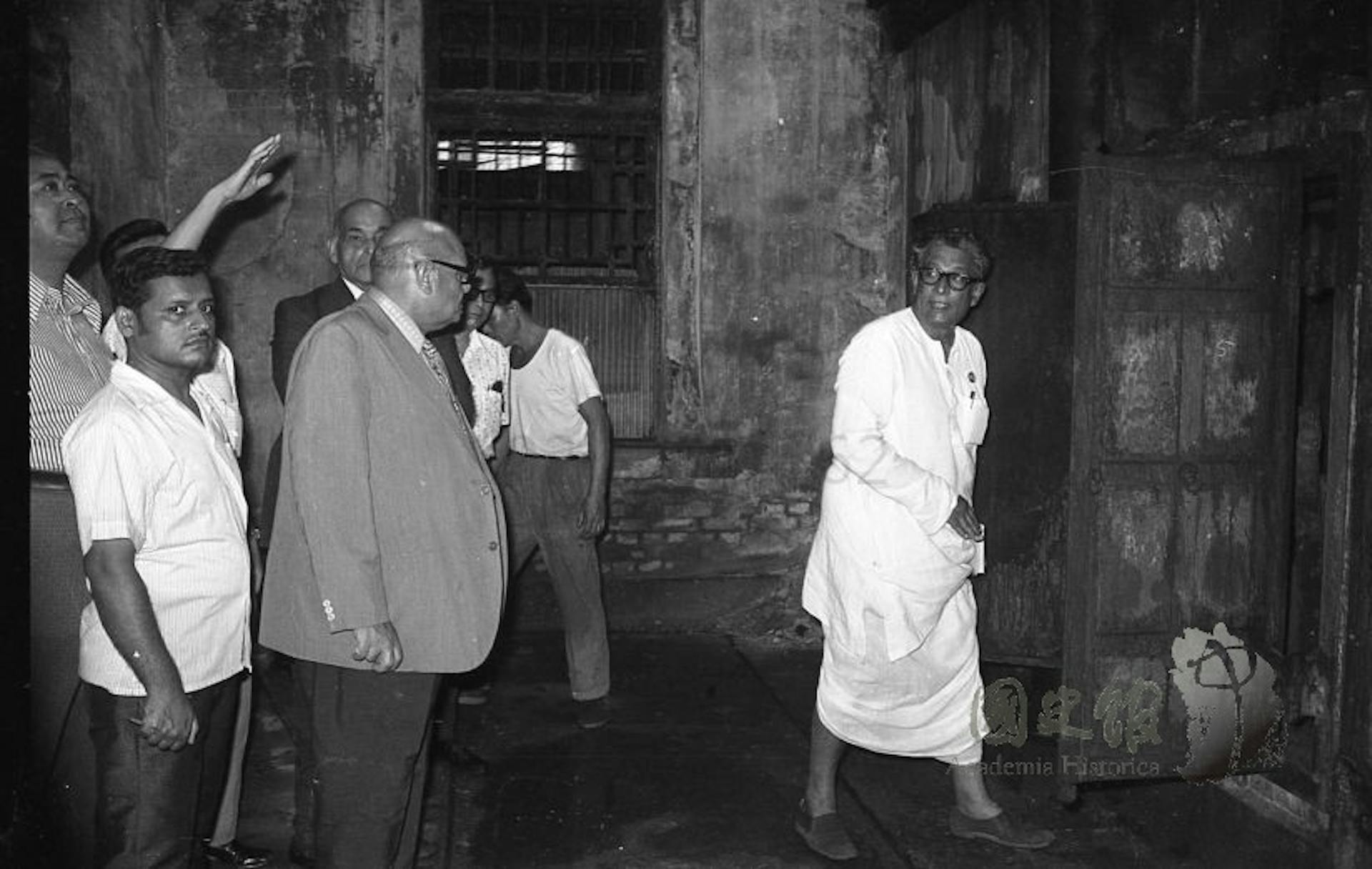

fter our walk around Taipei, Chao Yuan and I spent the week feeding the term “Bose” into Taiwan’s digital archives at the Academia Historica on Changsha Street. It was here that I first came across Samar Guha five decades after he visited Taipei. In the photograph, Guha is in a white dhoti and kurta, pointing at a crematorium. With each download, it was evident that Guha had been obsessed with solving the ‘mystery’ around Bose’s death. He was after his own holographic image of Bose.

In 1967, Guha had been elected to the Lok Sabha from West Bengal’s Contai constituency on a Praja Socialist Party ticket. In his maiden speech in Parliament, he raised the issue of making a fresh inquiry into the Netaji mystery. [3] In a few years, he would attain a position to assist the one-man G.D. Khosla Commission, which had been appointed by the Indian government to investigate the matter of Bose’s death a second time. Guha’s official title was ‘Convenor of the National Committee on Netaji.’

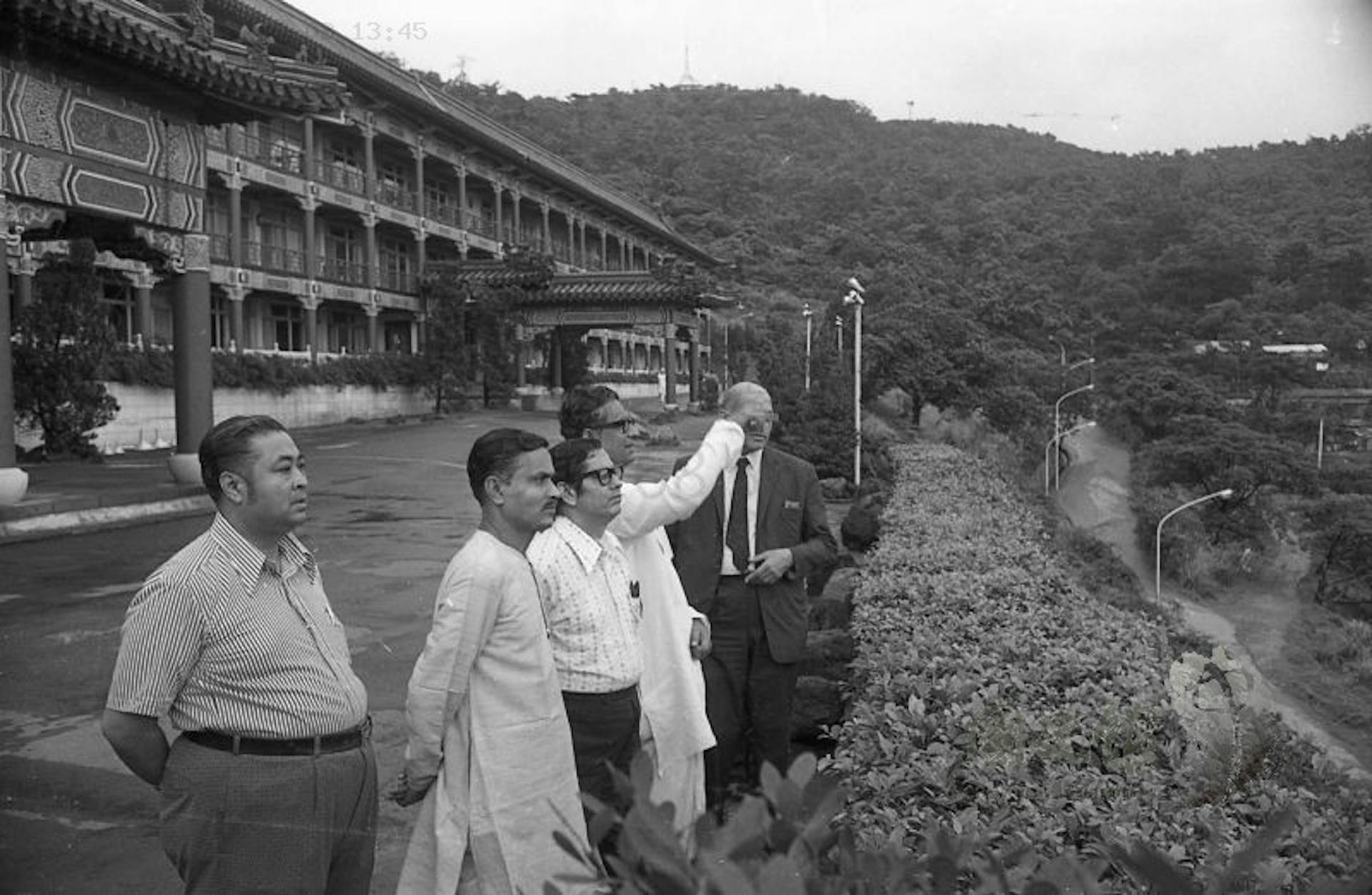

The Commission, the first Indian inquiry commission to land in Taiwan, held hearings in Taipei between 11 and 17 July 1973. Guha landed a few days earlier to line-up eyewitnesses. In this time, he also met the Foreign Minister of Taiwan, the Chief of the Southeast Asia Bureau, and several prominent members of the Taiwan Parliament.

The visit to Taiwan was only one of many journeys that Khosla, a former chief justice of the Punjab High Court, made around Asia. He also interviewed over 150 people in Japan, Singapore, Saigon, and Indonesia. After investigating alternate explanations, Khosla ultimately concurred with earlier investigators that the plane had crashed and led to Bose’s death.

Observers praised Khosla for leaving no stone unturned to arrive at his conclusions. He’d provided a hearing to some of the kookiest theories along the way. “His patience in listening to some tales is surely remarkable,” American historian Leonard Gordon wrote. “What could he, or anyone, have thought as he listened to the testimony of P.M. Karapurkar, agent of the Central Bank of India at Sholapur, who…claimed that he receives direct messages from Bose by tuning his body like a radio receiving apparatus.”

But Samar Guha was unhappy about Khosla’s findings. “What he produced as the report of the Commission can verily be described as an unusual specimen of a judicial chimera,” Guha later remarked in Netaji Dead or Alive? He wrote the book in jail in Rohtak years after the Taiwan trip, when he was imprisoned during the Emergency.

Guha pulled no punches. “After reaching the airport office, Mr. Khosla declined to get down from his car, refusing to personally inspect the old Taiwan runway,” Guha wrote. “Again we had to practically compel him to get into a jeep, and inspect the old Taihoku runway twice.” In Guha’s telling, Khosla had to be “dragged out of his hotel” to pursue the plan chalked out for the inquiry.

And the plan was elaborate and hectic. From Rooms 1003 and 1010 at Taipei’s Emperor Hotel, Guha and two of his colleagues painstakingly prepared a list of witnesses to be examined by the Commission. It was an eclectic bunch: a metalware manufacturer named Pritam Singh; Mr. Lu, a fruit producer and exporter; a staffer at the Ambassador Hotel, Mrs. Huang; and the Kuomintang’s director of information and cultural affairs, Professor Tsai.

Guha had even held a press conference the day after he arrived in Taipei. “Although Japan’s Domei News Agency has announced Bose’s death on 22 August, according to their inquiry, no Japanese ever saw Bose’s body,” the Lian He Pao newspaper reported on 9 July 1973. [4] Based on the evidence collected by the Khosla Commission over four years, Guha told the press, it seemed as if Bose had planned to visit Soviet Russia from Japan to oppose the British. Bose might have been imprisoned in Siberia by the Russians, he suggested. His death was a “fraud designed by specialists.”

As I clicked through pages of archival material, it appeared to me that Guha was an entire expert committee trapped inside a tall Bengali man. He was a forensics specialist, meteorologist, detective, journalist, and a politician—all at once.

“Citizens Above Middle Age”

efore the Khosla Commission landed in Taipei, Taiwanese newspapers appealed to their readers to help the visiting Indians. “If anybody knows more about the incident, please don’t hesitate to provide more clues,” one article read. When they caught wind of the news, journalists I-Han and Zheng Guang-Chen turned to “citizens above middle age” who may have been involved in security and military works in August 1945. They found that even 28 years later, people remembered the crash. It was no secret.

One such middle-aged man, Quan Zhang, ran an electrical appliances store in Taipei. But in 1945, he’d served as a Private in the Army Headquarters management department. “Quan told our journalist that he clearly remembers this event, for he stood guard 24 hours by Bose’s coffin which he said had Bose’s name on it in Japanese,” the Lian He Pao reported on 6 July 1973. “Then he pushed the coffin into a crematorium on Xinsheng North Road in Taipei with his own hands. He knew nothing after the cremation.”

Japanese officials had cordoned off the site after the crash. A sentry told Ming Yi Lan: “There were Indians dead in the plane.” He remembered his words for a long time.

Four people were stationed at the South Gate Military Hospital: Quan, two Japanese soldiers, and one Mr. Zhou. The Japanese returned home, and Zhou had died. Quan, 48 years old then, and the journalists had even visited the ward where Bose had reportedly lain. “The coffin was too big to fit in the incinerator, and they had to move the body into a smaller coffin. A white blanket covered the body,” the article read.

Lian He Pao reporters stayed with the story. There were several follow-ups over the next few days. Many readers called and provided clues:

- Chun Chang Lin, 48, forcibly recruited into the Japanese Army, worked at the Japanese Military Intelligence Bureau in Yangon, and learned of the event through an urgent encrypted telegram. It said: “5 to 6 passengers were killed instantly in the crash…” and that “the six bodies will be cremated and sent back to Japan. The military police and airport garrison collected the scattered jewellery and sent it to Japan.”

- Chuan Lin worked at the Japanese Air Force Hospital in Beitou. He vaguely recalled an Indian patient inside a ward for officers. The Indian was burnt and was said to be injured in a plane crash, but he didn’t know if he was Bose’s secretary.

- Sen Song Chu said he saw Bose’s cinerary casket in Nishi Hongan-ji Temple in February 1946. He recalled the casket was made of cypress, wrapped with a white blanket, and placed on the right-hand side on the second floor of the temple’s main hall. Its size was larger than others, which grabbed Chu’s attention. Bose’s name in Japanese was printed both on the casket and on the white blanket. The depositor was the Army Hospital.

- Ming Yi Lan, who worked for the Japanese Military as an overseer for the construction of Song Shan Airport, said he witnessed the crash. He served at Army Group no. 12807. Japanese officials had cordoned off the site after the crash. A sentry told Lan: “There were Indians dead in the plane.” He remembered his words for a long time.

- Tao Yung, president of the Sino-India Cultural and Economic Association, said they had received some phone calls narrating how the plane accident took place. The men who called, who had been forced to join the Japanese Army, had been put to work near Song Shan Airport.

Nothing Official About It

amar Guha felt he had been played by his own government about the Khosla Commission’s Taiwan visit. In 1973, the political circumstances in Taiwan were very different from Harin Shah’s 1946 visit. The Chinese Communist Party had won their long-running civil war against Chiang Kai-shek’s Kuomintang, and now held sway over the entire mainland, calling it the People’s Republic of China. The KMT and their Republic of China were confined to the island of Taiwan. The reversal of their fortunes meant that India and Taiwan lacked formal diplomatic relations.

Yet the compulsions of international travel required visas from host countries, especially when the trip involved hearings to solve a death mystery. As early as December 1970, an internal document issued by Taiwan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs discussed “how to leverage on the event” of the Khosla Commission visit. “Indian MPs who are friendly to our country suggest that we leverage this opportunity to stress the Indian Government to compromise on political issues, thus establishing a relationship between the two governments,” the document noted.

The Taiwanese wanted to know what was in the inquiry for them. In exchange for allowing the Khosla Commission’s visit, they wanted the Indian government to promise “to issue a visa for our citizens and officials to visit India or to attend international conferences from now on.”

The inquiry party at the crematorium on Xinsheng North Road, where Bose was cremated. Samar Guha is in the white dhoti and kurta, July 1973. Credit: Academia Historica

Letters and telegrams went back and forth between the Delhi-based India-Free China Friendship Committee (IFCFC) and the Taipei-based Sino-India Cultural and Economic Association. The Indians used placatory language as a diplomatic tool. Handwritten additions to Guha’s biodata made a case for his anti-PRC credentials: these included “Opposed to Communist ideology and opposed to Red China’s policy” and “Trying in India for developing good relations with the Republic of China.”

The Indians finally travelled on tourist visas, but a scathing editorial in the Taiwanese newspaper Zhong Yang Ri Pao best summed up the mood: “Currently, we don’t maintain diplomatic relations with India, and regarding Bose’s personal history, we have no particular reason to pay too much attention to his whereabouts.”

“Frankly speaking,” the editorial continued, “if the air crash took place within China, and the Indian government later sent a Commission attempting to enter the area now occupied by Mao, the members could possibly have been refused a visa.”

A week after the Commission returned to Delhi, on 25 July, Guha wrote a letter to Prime Minister Indira Gandhi. He accused her government of interfering in the investigations. He was angry that they had not obliged Taiwan by seeking formal permission for the visit. Three weeks later, Guha’s Unstarred Question No.3325 in the Monsoon Session of the Lok Sabha sought further clarification. He wanted to know whether a secret directive had been issued to purposely disrupt the investigation.

Surendra Pal Singh, the external affairs minister, denied the allegation. “In view of the fact that we have no diplomatic relations with Taiwan,” Singh explained, “it was suggested that the Commission may make independent inquiries without enlisting the formal cooperation of any official or non-official body in Taiwan and make its own arrangements on a private basis.”

“He spoke about Bose almost every day!”

Oh my god!” Sreemati Ghosh, Samar Guha’s daughter, exclaimed over the phone, “He spoke about Bose almost every day!” As a young girl, she didn’t pay much attention when her father spoke about his beloved Netaji. But recently, during the Covid-19 lockdowns in 2020, she stumbled on her father’s papers. She has since revised some of his books and translated them into English.

Guha, the three-time member of parliament, had a day job as a chemistry professor. Born in 1917 in Dhaka, he had been recruited to the Indian freedom struggle at a young age. “I think my father did see Bose once,” Ghosh said. “Probably when he was 17 or 18 years old, but from a distance. He didn’t meet or talk to him, but his guide Leela Roy,”—the Leftist politician— “who he would call Didi, was a close associate of Bose.”

“When I was young, I used to go to these picnics with my father. There were politicians, advocates, and academics,” Ghosh said. (Guha was an initiate of the Deepali Sangha, Roy’s political group.) “My father’s group always felt that the plane crash did not happen.”

Her father often shut himself up in his large study full of books. “It wasn’t just about Netaji,” she said. “He did lots of other work too. He was on committees for atomic energy, education, and would discuss matters related to the flood-prone areas of his constituency.”

Guha nursed his obsession with Bose up until his death in 2002. “He could never speak about anything light,” Ghosh said. “Until 2001, people came to my parents’ house. There was a big meeting in our living room. I think they were discussing the Mukherjee Commission.” To enlist support, he’d sent missives to at least three Indian prime ministers, one Indian president, numerous MPs and even to Soviet leader Mikhail Gorbachev.

“How the Indian people wish that the Nobel Peace Prize be presented to you, and you be hailed as the Man of Peace and Progress of the world!” Guha wrote to Gorbachev in November 1988, before placing an “earnest request” to reopen the mystery about Bose’s fate. His appeal to Gorbachev was part of a push for the formation of an expert committee to investigate stashes of secret documents believed to be lying in the USSR, UK, Japan, and the US.

Ghosh remembered that her father often invoked Bose when explaining his motivation for participating in public life. “He would say that in the West, politicians think of their work as a profession,” Ghosh said, “But Netaji repeatedly said you should love your motherland and become emotional about it. Don’t take this as a way to promote yourself; you should dedicate your life to public service.”

Sugata Bose, Bose’s grandnephew, believed that Guha, while obstinate on the point of Bose’s death, hadn’t misled people deliberately. “I think he was completely deluded on that point, and no amount of presentation of facts would work with him, but if you take out that delusion, he had genuine respect for Netaji.”

The Theories

even decades ago, Harin Shah wrote that some people in India “periodically provided the fuel and traded in the myth” of Bose’s death. The phrase rings true even in 2023.

Sisir Kumar Bose’s son Sugata served as a member of Parliament between 2014 and 2019. He is an historian at Harvard University, whose books include a biography of his legendary granduncle. “Most theories are absurd,” he said, about the death conspiracies. “But the worst, of course, is the utterly disgusting Gumnami Baba fabrication. It’s a cynical fabrication, calculated to demean and denigrate Netaji.”

The myth of Gumnami Baba—also referred to as Bhagwanji—has proved to be the most enduring one. The rumour was that Bose was living in disguise as an ascetic called Gumnami Baba. Advocates of the theory claimed that he’d been seen around various locations in Uttar Pradesh. It was also suggested that he chose to communicate only through devoted followers.

Wild tales proliferated about Bhagwanji. The last official enquiry into the ‘Baba Theory’ listed six hunches: he was one Krishna Dutt Upadhyay, a fugitive accused of murder; an Anand Margi; a CIA agent; a blind follower of Bose; Bose’s imposter set up by the Intelligence Bureau; and Bose himself.

Anuj Dhar, a Delhi-based author, and former journalist, has been one of the most prominent supporters of the Gumnami Baba theory in public. [5] In July last year, he appeared on YouTuber Ranveer Allahbadia’s channel, which has almost five million subscribers, for a lengthy conversation about the ‘Bose Conspiracy Theory.’ When I phoned him, he made his conditions clear. “I only talk about his death,” he said.

Dhar admitted to establishing the narrative about the Gumnami Baba theory in the early 2000s. Before that, he said, there were “too many helter-skelter” theories on Bose’s death. “Now, there are three theories of his death: the plane crash theory, the theory that he was killed in Russia, and the theory of the so-called Gumnami Baba.” In his 2012 book India’s Biggest Cover-Up, Dhar suggested that an ascetic living in Ram Bhawan, Faizabad was, in fact, Subhas Chandra Bose. “Justice Manoj Kumar Mukherjee’s inquiry did a lot of work on this angle,” he claimed. “In the report, they concluded that there are credible eyewitness accounts that this Gumnami Baba was Bose.”

“Since I was following the story for a long time, I came to know from sources that there was something wrong with the government reports.”

The public record suggests that Justice Mukherjee, who conducted the third official inquiry into Bose’s death in 1999, dismissed the Gumnami Baba angle, after the DNA test of the Faizabad ascetic’s teeth did not provide a match. Mukherjee had also travelled around India dismissing claims that Bose was a Mauni Baba of Sitapur, or one Sadhu Jyotirdev from Madhya Pradesh.

“Since I was following the story for a long time, I came to know from sources that there was something wrong with the government reports,” Dhar said, when I asked about the DNA tests. “And then Justice Mukherjee confirmed that the DNA test was fudged, but he could not prove it. He told me; he told my friends.” (I could not find a public record of Justice Mukherjee himself suggesting the DNA test was fudged.) [6]

Samar Guha with the inquiry party at the crematorium, July 1973. Credit: Academia Historica

At present, Dhar said, “there is hardly anyone else working on this” apart from him and a writer named Chandrachur Ghose. “Netaji’s death mystery has always been interesting since the matter is in the realms of state secrecy,” he said. “Not everybody has time. It is such a complex matter.” In 2016, both Ghose and Dhar deposed in front of the Justice Sahai Commission, which was the last in a series of official inquiries into the ‘Baba’ theories. Justice Sahai concluded that Bhagwanji was an “admirer of Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose but whenever rumour started spreading that he was Netaji Subhash Chandra Bose, he immediately changed his house.”

Dhar was angry about being termed a “crank” and a “conspiracy theorist.” He argued his research was credible enough to have earned him a lecture tour of America’s east and west coasts. “When I start removing the obstacles, the people on the other side start changing the goalposts,” he said. “By ‘other side’, I mean people who support the plane crash theory, including members of the family who have, all their lives, opposed the plane crash theory, but now they are supporting it.” [7]

Ashes to Ashes

o celebrate Bose’s 126th birth anniversary in January this year, the Indian government held a two-day event at Delhi’s Jawaharlal Nehru Stadium. On offer were a military show and tribal dancing. Tickets could be booked for free on the BookMyShow app. Bose’s family, based in Kolkata, disassociated itself from a birthday celebration held by the RSS at the city’s Shahid Minar.

They had their own commemoration planned at the Netaji Research Bureau, founded by Sisir Kumar Bose in 1957. The Bureau is in the house where Bose lived on Elgin Road. A programme was planned to focus on the equality and unity in the Indian National Army. “We will partly draw on my mother’s book where she features many of the people who were close to Netaji,” Sugata Bose told me before the event. “I will be personalising them. They were drawn from all different religious communities, linguistic groups, all genders and so on.” As part of the celebration, the KM Sufi Ensemble from Chennai also gave a concert.

In December 2022, I’d joined a line of school students wandering around the permanent exhibit on the first floor of the Bureau. We peeped into glass casings that held pages of Bose’s diaries and the uniform he wore as the INA’s Supreme Commander. In the Asia Room, I saw a magnificent samurai sword gifted to Bose in Tokyo in November 1943.

Later, I asked Sugata why the exhibit ended with Bose’s last public sighting: exiting a Japanese military plane in Saigon. There was no talk of his death. “My father wanted to keep the focus entirely on Netaji’s life and work,” he told me. “When he founded the Netaji Research Bureau, it was the terrain of conspiracy theorists telling fanciful tales. He wanted to avoid delving into all that.”

Over the years, the family had made trips to Japan and Taiwan, looking for closure. “My father went in 1965 and was very moved when he visited the spot where Netaji breathed his last,” Sugata said. “My mother had read about Taiwan in Harin Shah’s book soon after her marriage. She said she could not sleep or eat for days after she had read his account.”

The clamour to bring Netaji’s ashes back from the Renko-ji Temple in Tokyo has never really died out. In an ideal world, Sugata told me, the ashes would be brought home. “But if this is to happen, it must take place in a dignified way,” he said. Last year, Chandra Kumar Bose, another of Bose’s grandnephews, appealed to the government to bring back the ashes and order a DNA test. “Because of this procrastination in bringing back the ashes,” Chandra Kumar had said, “weird stories continue to circulate which demean the might and reputation of Netaji, including in films.”

Family members are not the only ones thinking about closure. Professor Chen, for instance, suggested that a small ceremony take place at the Nishi Hongan-ji Temple in Taipei. For Sugata, though, the issue of bringing back Bose’s ashes is relatively less important. “What is more needed in today’s India is following his ideals of equality and unity,” he said.

Sugata, the historian, has his own way of describing Bose’s death: “I felt I had to take a stand based on the historical evidence,” he said. “And I have faith that the younger generation of Indians and South Asians will be mature enough to accept the mortal end of a deathless hero.”

Sowmiya Ashok is an independent journalist and writer based in Chennai. She tweets @sowmiyashok.