The year is 2003. It’s a regular Sunday evening in Pune. A six-year-old sits glued to the TV. On screen, a silhouette of five people is accompanied by a hair-raising jingle. It is the start of Mission Everest on National Geographic Channel, and the girl can’t wait to see who gets eliminated this week. She is rooting for someone a magazine article would describe as “the oldest contestant and mother of two who left behind an ailing child to fulfil a dream.” [1]

The girl knows the “ailing child” referenced in the article: it is her brother, who had a fever at the time and was susceptible to seizures. And she obviously recognises Shubha Mehrotra, her adventure-loving mother, who’d left home three months ago and hadn’t been heard from since. The six-year-old girl, dear reader, is me.

The four other finalists of Mission Everest were from varying demographics: Kamakshi L.K., a college lecturer from Bangalore, was a shy 23-year-old who’d never seen snow; Akshay Randeva, a third-year student at IIM Calcutta, had almost missed his exams for the selection; Mandar Jadhav, a computer science graduate from Mumbai, was incredibly passionate about the armed forces; Gaurav Bajaj aka Golu, the youngest contestant at 19, was from the hill state of Uttarakhand.

Together with my mother, they’d been handpicked from a field of over 30,000 contestants to accompany a joint expedition of the Indian and Nepali armies to Everest, to commemorate the fiftieth anniversary of Edmund Hillary and Tenzing Norgay’s first ascent of the highest peak on Earth.

The selection process was gruelling: a preliminary longlisting round in one of the metro cities, followed by successive elimination rounds at the Nehru Institute of Mountaineering (NIM) in Uttarkashi. The trek would be even more exacting, a true test of physical fitness and patience. The final five would accompany the expedition from Lukla village to Everest Base Camp (17,600ft), from where the army people would proceed to the peak. This whole thing would be shot, edited and broadcast as a ten-episode adventure-reality TV show on Nat Geo. The show aired on Sunday evenings in the summer of 2003, from 20 April to 16 June.

For about a decade prior, network executives had been betting on the idea that Indians loved watching ordinary people on screen. The quiz-show format was an obvious winner. What started with passionate school students in Derek O’Brien’s Bournvita Quiz Contest in 1992 had evolved into the glitzier game of Kaun Banega Crorepati in 2000, franchised from the British show Who Wants To Be A Millionaire? In between the quiz shows, the 1990s birthed multi-season singing-and-dancing talent shows that became staple primetime entertainment: Antakshari (1993), Sa Re Ga Ma (1995), Boogie Woogie (1996).

Mission Everest represented a new kind of reality TV. There were no professional actors, pre-decided scripts or captive audiences. It was one of the first Indian reality shows to be shot almost entirely outdoors. The show’s plot points were often products of spontaneous exchanges between executives, camera crew, and serving and retired soldiers.

But with reality comes unpredictability. From inception to broadcast, the show ran into a number of unforeseen—and unforeseeable—challenges. Some were logistical. Others were induced by the demands of the reality TV genre. Conflicts surfaced between participants and camera crew. Tasks were stretched a little too far. Drama was solicited and sometimes manufactured. It was nothing like the raucous reality TV landscape of today. But it contained its seed.

What follows is an oral history of one of India’s earliest ventures into reality TV proper, told in the words of those who were a part of it.

“We can spin this around”

ilshad Master (Senior Vice President, National Geographic Channel, India): It all came about because of my father-in-law, Colonel Bull Kumar. [2] You must have heard of him. He was the first man from India to climb Everest and the first one on the Siachen glacier. We were at the Delhi Gymkhana one evening, and he told me the Indian Army was sending an expedition to commemorate 50 years of the first climb to Everest. He said to me, ‘See, my boys are going to the top of Everest, what are you going to do about it?’ I said, ‘If your boys take five of our people along with them, then I will make a TV show and telecast it on Nat Geo.’ So he said ‘Done’ and I said ‘Done’ and we both chugged our beers.

Siddharth Bahuguna (Cameraman and Series Producer): I was just done with Channel V Popstars when I got a call from Dilshad saying the Indian Army is going to Everest, can you embed with them. I said yaa, why not. The idea was to spend three months with them and capture this expedition: it didn’t start off as this reality show concept. I got to Delhi and we started talking about it, and then the sales guys from Nat Geo got involved and said, ‘Hey we can spin this around, get more advertising. Why don’t we get normal people along with the army?’

Ramon Chibb (Executive Producer, National Geographic Channel, India): The problem was that there was not much precedent to this. What happens in a normal documentary is that you go with one camera, follow the subject, do research, and then decide ‘I want this shot, that shot.’ But this was different. We studied a few international reality shows, I think one of them was Survivor. That’s when we realised that if we want to show real emotion, we need to capture every moment. That became the driving force.

It also became a logistical nightmare. We ended up taking some seven cameras, unlimited tape, and shot literally everything that happened. We came back with some 500-600 tapes, which was an editing nightmare!

Siddharth Bahuguna: Even before Mission Everest, Channel V was commissioning a lot of adventure shows which were taking common people out of their comfort zone and putting them in uncomfortable situations: shows like Patli Gali, [3] Gone India, [4] and [V] On the Run. [5] They were just not marketed as ‘reality TV’ yet.

Then, in 2000, Channel V Popstars changed all that. For the first time, the word ‘reality’ came into play. Marketing and advertising stepped in. Hoardings were plastered all over the country, thousands queued up for auditions.

Abhinandan Sekhri (Producer, Highway on my Plate, Jai Hind with Rocky and Mayur): It’s not like India discovered reality TV by itself. In 1992, when cable TV first came to India, there were four main channels: Prime Sports, MTV, BBC and Star Plus. Star had a very successful run because it was the only entertainment game in town. But by the early 2000s, there was some solid competition. There was Zee TV, Sony and Colors, and as a result, Star completely lost market share. [6]

But then they made Kaun Banega Crorepati in 2000, which was a xerox of Who Wants To Be A Millionaire. It was a big gamble: Bachchan was rumoured to have been paid an obscene amount of money, something like ₹18 lakh per episode. And the gamble paid off. After KBC, Star became number one again. This started the whole ‘See what has succeeded in the West and paste it here’ trend. After KBC, there was Dus Ka Dum, Indian Idol and Bigg Boss, all copied from the West. People started injecting the ‘reality’ element into everything.

“To really understand what was possible, all of us used to do rounds of push-ups at the Nat Geo office in Noida.”

Dilshad Master: Nat Geo was a new channel in India then, and all our money would go towards dubbing English shows into Hindi. Mission Everest was Nat Geo’s first TV show for a primarily Indian audience. We structured the entire channel around this show, gave it a prime slot on a Sunday night, bookended it before and after with great content, and advertised the hell out of it on radio and TV. We worked so much those three months. I ended up sleeping in the office most nights and asked Zubin, our Managing Director, to buy me a bean bag. But he said we didn’t have the budget for that.

Ramon Chibb: We held initial selections in four cities: Mumbai, Delhi, Chennai and Kolkata. But we were still unsure of the criteria. That’s where Colonel Bull Kumar came in. We picked his brains, and decided to weed out contestants army-style. In the initial selections, we had one day in the city to winnow the top 50 contestants out of thousands. So we made them run, do push-ups and a few other physical exercises. To really understand what was possible, all of us used to do rounds of push-ups at the Nat Geo office in Noida. It was like, okay, I can do 50 and he can do 60. So accordingly, we set the criteria. And then we had the girls, who needed to have their own parameters. So we told Dilshad, ‘Chal, you also do push-ups.’

“They were in a putty parade”

andar Jadhav (Finalist): It was mainly the Indian Army that got me into this. I really wanted to join the armed forces, and this was my chance to interact with some of these army guys. Initially, we had thought they were going to take us all the way to the peak. If you see the ads for the show, they all say, ‘Youth of India! I will see you at Everest.’ So of course, you think you’re going all the way to the top. Who thinks all this rigmarole is just for basecamp?

Akshay Randeva (Finalist): I was in IIM Calcutta at the time, and a bunch of my friends were going. You know how college life is—on any given day you have nothing better to do, so I tagged along. The way we were looking at it was very much that this is a paid trip to Everest with Nat Geo. We did see the cameras when we got there, but it didn’t really register.

Shubha Mehrotra (Finalist): The moment we started running, we noticed the cameras everywhere. They didn’t make any difference to me really. It was just like, yaa okay, whatever, there is some TV element to all this. I was just focused on the selections. I did see a lot of people who were nice and stylish, who the cameras were attracted to: people with nice running shoes and branded gear. I remember thinking that if they are looking for glamorous, hep-kinda people, I have no chance here.

Neeraj Rana (Vice Principal, NIM, in charge of selections): Nat Geo wanted 20 finalists to make their way to some mountaineering institute for the final selection and rejection. They gave us an initial plot line, and we gave them all the technical help.

Shubha Mehrotra: They took us to NIM to narrow us down from 20 to five. Now at the bottom of this hill, they suddenly stopped the bus and ordered all of us out with our bags. From there, the whole tone seemed to shift. Until then, it had been nice and fluffy. We were playing games, singing songs. As soon as we reached NIM, the whole military discipline thing started.

They were all like ‘Get down,’ ‘Fall in line.’ Our first ‘task’ was to pick up our bags and run uphill to the NIM entrance. I didn’t have a proper rucksack or anything. I had a handbag with two handles, so I put those handles around my back like a sack. There were some people who had gotten suitcases: they literally put them on their heads and walked up. That was the first big shock, an indication of what was to come.

Akshay Randeva: My formative years were spent in Rashtriya Indian Military College, right? I have dealt with fauji instructors. It was no surprise to me. But for all the civvies, it was quite shocking, quite suddenly the Full Metal Jacket sort of treatment, if you’ve seen the movie. They were in a putty parade [7] and had no idea what was going on!

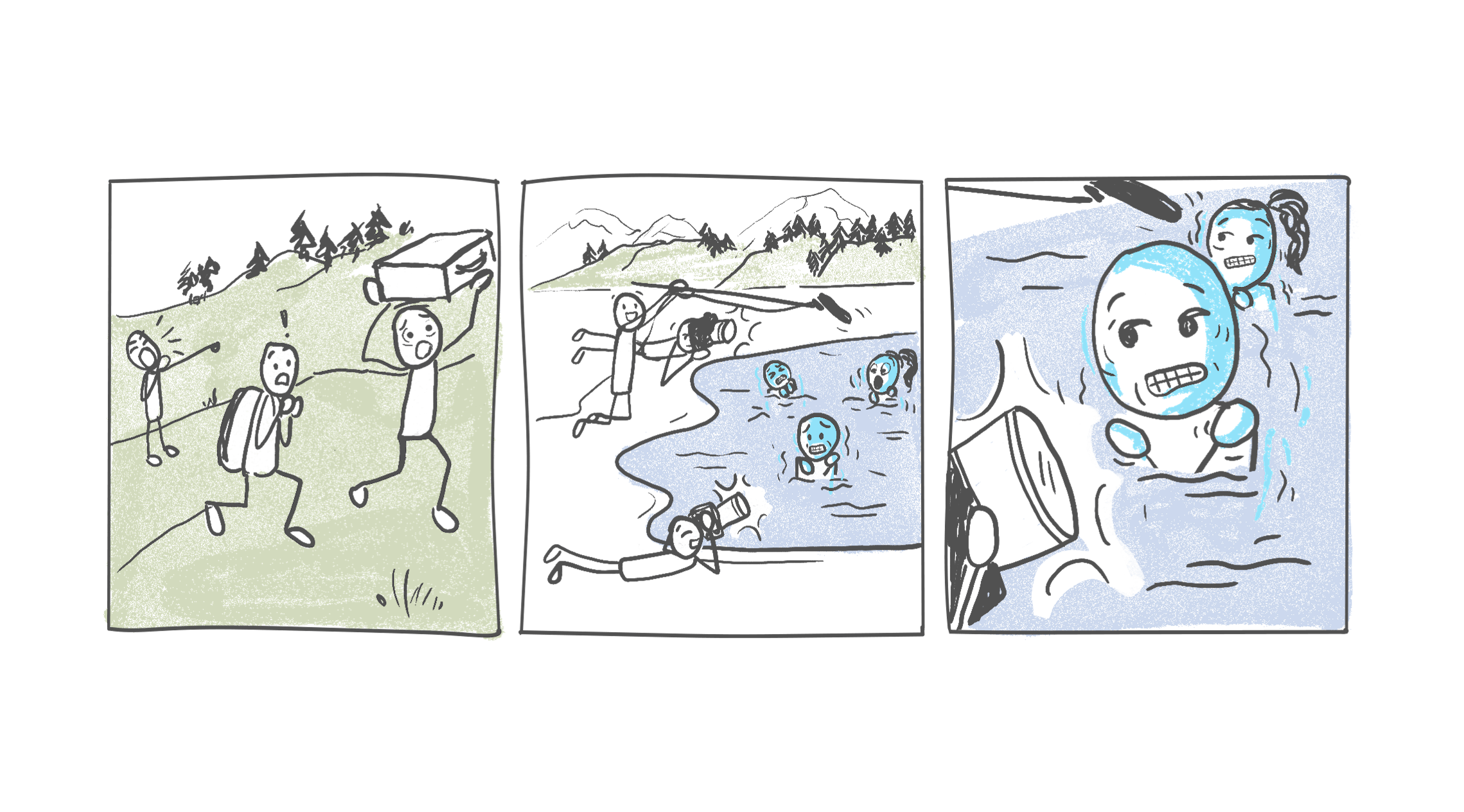

Kamakshi L.K. (Finalist): The next day, they woke us really early and made us jump into a freezing lake. Like, you’re getting people here from South India, people who have lived on a beach all their lives, and making them jump into a freezing lake in sub-zero temperatures. And on top of that, when we were all wet and shivering, they thrust the camera in your face and asked, how are you feeling?

“The cameramen were not here because of us. We were here because of them.”

Mandar Jadhav: The cameras were extremely irritating. It’s early morning and we’re in freezing water, and there’s a cameraman in front of you going, ‘Aapko kaisa mehsoos ho raha hain, how are you feeling?’ Or when you’re doing push-ups, and you’re already thoroughly tired and just can’t do another: ‘How are you feeling?’ I mean, what kind of a question is that!

One thing I realised early on was that this was a show. The cameramen were not here because of us. We were here because of them.

Akshay Randeva: The reality came out very quickly: this was not going to be as much of a walk in the park as we had thought. They wanted it to be a show, and for a show, they needed to get a rise out of us.

Mandar Jadhav: I remember the first elimination. After the first day of training, we had an interview with Neeraj Rana, who asked us, what do you think of so-and-so teammate? And when it turned out that nobody liked this one or that one, we realised that ‘Oh, what the hell. These guys are using this information to conduct eliminations.’ They were turning us against each other—you know, he said this, and she said that, those kinds of things.

Kamakshi L.K.: It was so rude. No ‘Good job,’ no ‘Good try,’ just ‘You’re not good enough, so please leave.’

Akshay Randeva: The elimination was never done when you expected it. It was always during a bus ride, or when you got up in the morning. They could have chosen different processes to conduct those eliminations but they chose this random shock value thing. So I felt it was more to get some reaction out of everybody else. There were some tears-vears, which they might not have gotten if it was more organised.

Mandar Jadhav: All this used to happen during ‘Ragdaa’ mode, that’s what we called it. Ragdaa mode. Hardcore mode.

Neeraj Rana: I was the villain for all of this. Naturally, when you’re responsible for selecting and rejecting people, you become the villain. Everyone called me Butcher Major.

I didn’t feel bad about it. Actually, while shooting, I didn’t fully realise what was going on. And then one day I was travelling from Dehradun to Delhi in a Shatabdi, and I noticed people staring at me. Am I not wearing my tie correctly or something, I thought. And then finally one 14-year-old girl came up and asked, ‘Are you the Major from Mission Everest?’ That’s when it hit me that people had recognised me from the show, but no one had the guts to walk up to me.

Akshay Randeva: I actually thought I wouldn’t make it to the final five. I’m not a good on-camera guy. I spent most of my time trying to avoid the cameras, and I don’t think they got a lot of emotional output from me. Personally, I thought Shubha and Kamakshi were definitely in. It was a beautiful story, right? A housewife from Pune, no connections, going all the way to Everest. Then there was Kamakshi. She was naive, innocent, had never seen snow in her life. That’s ideal, na? Take a South Indian to Everest!

Out of the guys, I felt like it could have been any of us. I think they wanted people from different backgrounds, different age groups. They built a group they can do TV around. I don’t think it was purely based on capability.

“If there’s no drama, what’s the fun?”

hubha Mehrotra: So the final five were selected, and the hike to basecamp began. Neeraj Rana was no longer there: it was just us and the camera crew. Those guys would come up to us and ask: What are we finding hard? How are we feeling? Sometimes it was purposely emotional stuff. My son Dhruv was sick. They would bring that up, and ask me stuff like ‘Are you missing home?’ I remember this one time I was almost ready to cry, and they sensed they could get some good byte here. They came and asked me some questions about my ability to do all this. But I just turned my back and controlled myself. I refused to give them what they wanted.

Kamakshi L.K.: In the middle of the trek to basecamp, we decided to strike, all five of us. We refused to move forward till they provided us with better equipment. Warm blazers, better shoes. We were all dressed in our old, flimsy sweaters and tracks. None of us had anything warm enough for basecamp. So in the middle of the hike, they bought us some tracks and blazers, just from a local shop on the side of the road. They bought us shoes too, but they were such bad quality that they fell apart even before we reached basecamp.

Akshay Randeva: At NIM, the Nat Geo guys could take a step back, because the NIM guys were doing the ‘ragdaa.’ When the actual trek started, there was this second shift of gears where the camera people now had to take control, and basically, they overdid it. A couple of them said a couple of things to a couple of us that pissed us off.

If you ask me, we didn’t really need the gear as much as we needed an apology. Siddharth had overplayed his hand. They had to shoot, they had to finish the show, they had nothing to hold over us anymore. If we decided that we didn’t want to do this anymore, they were screwed right? Somewhere on that trek, we realised that the power equation was not what they were making it out to be.

Siddharth Bahuguna: The girl from South India was getting very edgy about the food, and at one point, we came to loggerheads. There was a complete breakdown, where all five of them ganged up on the three of us camera people, saying that they wouldn’t go forward. When you’re physically tired and hitting high altitudes, your irritation levels are always higher. So small things become big things.

Now it was at this point that I had to point the camera at myself and explain what was going on. That see, ‘I am the director and this is what is happening inside the show.’ That became part of the episode. It had to.

Mandar Jadhav: It was two camps before basecamp, just before we halted at Kala Patthar. That is the time this Siddharth character started poking us. He was like, ‘No no, you should not go forward, you should demand that things be supplied to you.’ Now, when you see the episodes, he himself is giving a soundbite on camera, that these contestants are demanding these things which we are unable to supply, when in fact, it was his idea for us to do that. That guy was a character, man. After seeing the episodes now, I’m just like, this guy was a prick.

Siddharth Bahuguna: Okay yaa, it’s possible that I could have started this drama. I needed a fast point. We had to make a series, yaar. If there’s no drama, what’s the fun. Everyone’s just walking. Yes, I’m 200 percent sure if somebody mentioned that I had started this strike-vike, it must be true.

Ramon Chibb: Dirty politics, it was all dirty politics. I don’t want to go there. Keep it a happy article about the first adventure reality show!

I will tell you honestly, after the final selections at Damdama, it was just a cake walk. There were no conflicts to make an episode really. What were we supposed to shoot? So certain conflicts you want to create.

Akshay Randeva: This is a discussion I had with Siddharth also, that they should have continued with the eliminations all the way to basecamp, and had only one person reach the top. Because then, they would have had something over us and we would have behaved ourselves over the course of the trek.

Shubha Mehrotra: On 1st April, I thought, let’s fake altitude sickness and pull an April Fool’s prank on these camera guys. Because they used to keep asking us, is anyone feeling sick? I think they were hoping that someone would get altitude sickness. They had already told us all the symptoms, so I just put my sack down and repeated the symptoms. That I can’t breathe, my head is spinning, I feel nauseous. So for most of the day, Sid walked with me carrying my sack. Once we reached our destination that evening, I told them that see, this was April fool. ‘Ask Kamakshi, nothing has happened to me. I just made you carry my bag.’ We had a good laugh, and that was all there was to it.

But then I saw that they ended up using this bit in the show. They made it out like I’m actually struggling and I have real altitude sickness!

Mandar Jadhav: It’s only in hindsight that I can see all this clearly. At the time, I was so overwhelmed that I didn’t even know what’s happening. Every time I talk to Ramon about Mission Everest, he always has this naughty smile on his face. So I know something was wrong. I was just a dumb 19-year-old, I hadn’t seen anything of life, I had never even ventured out of Bombay.

“Today’s reality TV has no lines”

bhinandan Sekhri: For reality TV, one of the main elements is contrived drama. Maybe in the beginning, the genre wasn’t so contrived. But look at Bigg Boss, Season 1 to Season 8. In the beginning, it was good enough just to see people compete. Then it became more and more insane, and it wasn’t just that it was scripted in, which I’m quite certain that it was. It was also that the performers knew that their relevance was only based on how outrageous they could be. If you’re a rational, sane voice arguing a point in a rational, sane way, you don’t make for compelling TV.

Akshay Randeva: Back then, people were still figuring out the boundaries and how much they could push them. Siddharth was naughty, but he was also careful about lines. Today’s reality TV has no lines. It takes a certain kind of person to put yourself out there like that, and one thing I realised after Mission Everest is I’m definitely not that kind of person. I don’t think I could do it today. Because the show would be very different today.

Siddharth Bahuguna: Now, it’s scripted reality. I am literally telling people, ‘I want you to do this, behave in this way, react in this way.’ They’re sketches. In between the stunts, I will have a bit of scripted reality, and everyone will know exactly what they have to do. It’s all a game of numbers, of getting more eyeballs. In the industry, they’ve even come up with a new name for this: Factual Entertainment.

Abhinandan Sekhri: Reality TV became garbage, yaar. They just change these nomenclatures for respectability.

Ramon Chibb: See, we may have used a few of these tricks, but for the most part, it was real people, real situations, real life. Before Mission Everest, reality shows gave tangibles, like one crore in prize money. You play Kaun Banega Crorepati and win one crore, or you become a Channel V Popstar and record an album. But we gave people an experience which eventually built careers. Mandar finding his calling as a defence officer and becoming one of the best fighter pilots in the Air Force was a very proud moment for us. As you know, adventure changes a person’s personality. It really builds character, makes a different person out of you. So we would like to believe that we did something real.

Mandar Jadhav: When I came back from basecamp, I got a call back for a Mahindra British Telecom [8] job. The interview lasted an hour and a half, out of which one hour I spoke only about Mission Everest. I got the job, worked there for a while, and then one fine day, I just stopped going to work. I wanted to join the army and that was that. In a way it’s true, Mission Everest really changed the course of my life.

Shubha Mehrotra: There were rumours at the time that the final five would get Hero Honda motorbikes. You know, because Hero Honda was one of the sponsors for the show. The five of us used to keep speculating about this. What will we get at the end? Because after such a long selection, we should get something, no? Even in all those Saa Re Ga Ma shows, the winner gets some big thing at the end. All those sponsors, and in the end, we got absolutely nothing out of it.

Okay, I guess we got to go to Everest. That was enough for me.

Neha Mehrotra is a freelance journalist who divides her time between Pune and Delhi, and tweets @nehamehrot.