In late 1979, a Delhi-based magazine called Probe India ran an open letter written by four law professors objecting to the decision of the Supreme Court in Tukaram vs State of Maharashtra. The matter was widely known as the Mathura case, after the minor Adivasi girl who complained that she had been raped by two constables in a police station in rural Maharashtra.

The Supreme Court had agreed that a sexual act had taken place, but thrown out the rape conviction. “There is a clear difference in law, and common sense, between ‘submission’ and ‘consent,’” the open letter stated, addressing Supreme Court Chief Justice YV Chandrachud. “Consent involves submission; but the converse is not necessarily true.” The court had established that Mathura appeared to have submitted to her ordeal. “But where,” the writers asked, “was the finding on the crucial element of consent?”

The fire lit by that letter swept through the lives of many Indian women. It changed them, and those who came after them. The movement it boosted gave Indians a vocabulary to describe sexism and misogyny that many of us still use. It attempted to unite women outraged by the rape trial of an Adivasi teenager. Its participants thought of its goal as “simultaneously” [1] fighting sexism, casteism and religious chauvinism. It was a protest against something that slides out of focus even in 2020, when police violence has become a focal point of dissent around the world: the matter of custodial rape.

Looking back at that movement gives us an unforgiving view of what the 1970s and 1980s were like for many women, as well as how little seems to have changed in the way states exercise their monopoly on violence. In the years since, many Indians, and the media they consume, have changed how we talk about consent and sexual agency. But the realities underpinning our language are stubborn. The roots of injustice persist. Inequality gets in the way, still, of the fundamental re-imagination that began for many women on the day they read that open letter.

Mathura

ibhuti Patel, aged twenty-four, picked up a copy of Probe India from a Wheeler’s bookstall at a Mumbai railway station. She was part of a loose collective that used to call itself the Socialist Women’s Group. As a sixteen year-old growing up in Vadodara, she’d joined a leftist group and participated in trade union struggles.

Her work included translating material from English to Gujarati, and organizing study circles on socio-economic matters.

She made several copies of the open letter on a cyclostyle machine and posted them, with four-rupee stamps, to fellow activists. One of these was Sonal Shukla, an educator who had grown up hearing stories about ordinary people who’d given shelter to protestors during the Quit India movement. Her home in Vile Parle, where the Socialist Women’s Group often met, was an open house for union workers and committed Trotskyists.

“I’d think, ‘why is she coming and interfering in my private domain, let her go and do the revolution.’”

Shukla herself had provided refuge to Gayatri Singh, who led group meetings and worked in labour law at the time. Shukla watched the action in these gatherings from the sidelines. “My role was just that of a supporter,” she remembered. It was how she’d met Vibhuti Patel, who came into her kitchen one day to offer help cooking for her political guests. “Initially I used to be upset,” said Shukla. “I’d think, ‘why is she coming and interfering in my private domain, let her go and do the revolution.’” But they became friends, and Sonal Shukla became actively drawn into discussions about feminist theory and women’s rights.

The Socialist Women’s Group was one among many autonomous women’s groups emerging across India. Starting in the late 1960s, women had been increasingly active in rural and regional agitations. Many of these early struggles were related to economic issues: class consciousness, landless farmers resisting economic oppression, lower middle-class women protesting against price rise in the metros.

These movements connected women with others like themselves, who refused to be passive spectators in their personal and political lives. Chhaya Datar was a homemaker in Mumbai who’d turned to social work, conducting workshops with Adivasi women in rural Maharashtra. Flavia Agnes was regaining control of her life after leaving a thirteen-year-long abusive marriage. In Bengaluru, Donna Fernandes was working on water and housing issues with women from slum communities. In Hyderabad, Vasanth Kannabiran was beginning to address gender issues with a small group of women.

The open letter about Mathura’s case caused a new awakening among some of these women, who are now among India’s most renowned feminist activists. “It made me so angry, you can’t imagine today. That’s when I felt I couldn’t be an outside supporter as I thought I would be,” Shukla told me. “So far, I was working for women, but now I wanted to work as a woman. That difference came with the Mathura case.”

n March 1972, the orphaned Mathura was between fourteen and sixteen years old. She lived with her brother in Maharashtra’s Gadchiroli district and worked as a labourer. She was in a relationship with Ashok, the cousin of a woman at whose house she sometimes worked. Likely opposed to the relationship, Mathura’s brother complained that Ashok and his family had kidnapped Mathura. The Gadchiroli police brought them all to the local station at Desaiganj to record their statements, a procedure that lasted well into the night. At half past ten, as they were about to leave, the policemen asked Mathura to stay back.

The lights of the police station were switched off and doors bolted. One of the constables allegedly raped her inside the bathroom. The other officer, intoxicated, allegedly molested her. [2] A crowd of villagers gathered outside the station brought the head constable from his house and forced him to lodge a first information report.

A medical examination about 24 hours after the assault claimed to have found no physical injuries or semen in the vagina, though there were traces of seminal fluid on her clothes as well as on those of the constable. The report further concluded that Mathura had had sexual intercourse in the past.

In the trial court, two years later, the constable argued that the intercourse occurred with consent: the absence of injury proved as much, didn’t it? The court not only ruled in favour of the constable, but declared Mathura to be a woman “of easy virtue.” She claimed rape, the judges said, because she wanted to appear virtuous to Ashok. [3] On appeal, the High Court overturned the lower court’s judgement, taking many factors into consideration: Mathura had been summoned to the station in the dead of night; she had immediately communicated the fact of her rape to the crowd outside the station; she could not have successfully resisted her assailants. But the Supreme Court restored the verdict of the trial court. In agreeing with its conclusion, it declared that “stiff resistance being put up by the girl is all false,” and that “the alleged intercourse (was) a peaceful affair.”

The year was now 1978. Six years had passed since Mathura was told to stay back on a late night in a police station in Gadchiroli.

atel’s group sent the open letter to fifty women, along with some groups. Sonal Shukla recalled that forty-nine women gathered for a meeting in Mumbai in January 1980. [4] All of them agreed on two central demands: justice for Mathura, and an amendment of the rape laws.

At the meeting, they founded the Forum Against Rape, which would later rename itself the Forum against Oppression of Women.

The new group invited people to come out in protest on 8 March, International Women’s Day. People came. Women marched through the streets of Old Delhi chanting: ‘Supreme Court, Supreme Court, against you where can we report?’ Over a dozen organisations in the capital put on skits and sang songs. There were gatherings in Surat, Hyderabad, and Bengaluru. The Forum gathered thousands of signatures in support of its demands. Women’s organizations filed a petition in the Supreme Court seeking a review of the Mathura decision, but the bench threw it out: it held that the groups didn’t have the right to demand review.

In November that year, the Forum hosted a national conference at Dharamshala, a marriage hall in Mumbai’s Khar area. “We were expecting around eighty or ninety but actually about four hundred people came,” Patel recalled. “There were artists and filmmakers and students and teachers and mine workers. Women across class, caste and cultural backgrounds had come.”

The November 1980 gathering took place in a marriage hall in Mumbai’s Khar area. Credit: Vibhuti Patel

The participants did everything themselves, from translations to cleaning the toilets. They all slept in one hall. In the mornings, they rolled up their beds and queued for the bathroom. The meetings began at 10am sharp, and those who didn’t manage to bathe joined in their nighties. [5] Sitting cross-legged on the carpeted floor with papers and notebooks, they argued, screamed and agreed as they drafted the suggested amendments to the rape laws. [6]

Vasanth Kannabiran, who travelled from Hyderabad for the conference, was delighted: she no longer felt alone. “I will never forget that. It was one of those things that you need to experience in your life,” she told me.

Emergency

t had all been building up. Less than half a decade earlier, the United Nations had designated 1975 ‘International Women’s Year.’ It held a conference in Mexico, and requested status reports from member countries. In India, a government-appointed committee put together ‘Towards Equality,’ a report that confirmed a storm of bad news for the country’s women: a declining sex ratio; systematic exclusion from the processes of modernisation and capitalism, and a lack of political representation.

‘Towards Equality’ was a milestone. It crystallized an already-developing interest in the new social movements of the early 1970s, particularly in Maharashtra. One early initiative, the Shahada movement, was spearheaded by Bhil landless labourers in the face of crippling drought and famine. Within a couple of years, the movement’s women associates started to protest gender-specific issues. They marched to liquor dens and broke pots of booze as part of anti-alcohol agitations. Later, they began to attack wife-beaters in public and force apologies out of them. [7]

Drought conditions over 1972 and 1973 had caused prices to rise sharply even in cities, and women across classes had begun to mobilize. In 1973, to protest the rising price of milk, a group forcibly entered the Aarey Milk Colony in Mumbai and stopped trucks from leaving. About thirty women gheraoed the agriculture minister in his chamber for four hours, demanding more affordable milk. In 1974, more than 8,000 women brandished rolling pins on a march in Mumbai. “Pav do, gehu do, nahi toh gaddi chhod do!” they chanted. Give us bread, give us wheat, or else get off that seat!

The agitations spread to Gujarat, when thousands of middle-class women joined forces with what came to be known as the Nav Nirman movement against corruption and rising prices. [8] An anti-inflation protest could not raise the questions an anti-patriarchal movement would. Still, it represented a kind of collective public action by women that hadn’t been seen for decades after independence.

Urban middle-class feminists followed the women’s lib movement in the United States with keen interest. They were also tracking women’s participation in anti-imperialist agitations in Vietnam, China, and the Soviet Union. Meanwhile, the Progressive Organisation of Women, [9] founded by activists associated with the Maoist uprising of the 1970s, highlighted two structural problems: the sexual division of labour and the culture that rationalized it.

Then, in 1975, Indira Gandhi imposed the Emergency––and women became part of the resistance. No clear country-wide data exists to date, but we do know that over five hundred women were arrested in Maharashtra alone. [10] “People began to see the state through its instruments,” said Uma Chakravarti, noted historian and filmmaker who made a documentary about the imprisoned actor and social activist Snehalata Reddy. [11]

Some of the women who were tortured and harassed in prison began to speak up after the Emergency ended in 1977. In left-wing groups, a sense of dissatisfaction grew, as women “were feeling suffocated within the political structures of these groups,” Patel remembered. “They were used only as tools for fundraising and had to obey the orders of male leaders.” Constrained by male hierarchies and preoccupations, they began to look for spaces outside, amongst each other.

Towards the mainstream

“Women’s movements are always born out of larger movements,” Sonal Shukla told me.

When Patel’s Socialist Women’s Group organized a workshop in 1978, many women attended, eager to share ideas and improve coordination among their organisations. A printed newsletter called Feminist Network was put together in Shukla’s house. A cyclostyled Hindi publication called Stree Sangharsh, ‘Women’s Struggle,’ was born. The influential magazine Manushi began to be published out of Delhi.

“There was a joke,” Patel said. “If you meet one activist, he is an institution; if five activists meet, they start a newsletter.” In the era of cyclostyle machines, revolutions were homegrown because there was no other choice. “People had to learn the technology because there were severe curbs on freedom of expression during the Emergency.”

Two outrageous instances of custodial violence became flashpoints for these women. In Hyderabad in 1978, Rameeza Bee was taken to police custody and raped by four policemen. Her husband was beaten to death for protesting. The officers who falsely implicated Rameeza Bee of being a sex worker faced no repercussions. The incident led to widespread violence in the city and the police fired at protestors, killing a number of them. Kannabiran and a few others founded the Stree Shakti Sangathana in this period. The enquiry into Rameeza Bee’s case revealed “what it meant to be a woman,” Kannabiran wrote in her memoir.

In 1980 in Uttar Pradesh, Maya Tyagi was paraded naked by policemen and violated by a lathi in police custody. Her husband and his two male companions were shot dead. During the judicial inquiry, the policemen argued that Tyagi was the sexually promiscuous mistress of a dacoit. The officers faced no charge, because there was no penile penetration.

In the era of cyclostyle machines, revolutions were homegrown because there was no other choice.

The public outcry against custodial rapes hadn’t yet made a difference. In 1979 in Bengaluru, Donna Fernandes formed Vimochana with the aim of spreading awareness about women’s issues before an upcoming election. “There was a lot of resistance against us when we started. We were called all kinds of funny things,” Fernandes said. [12]

In 1980, the Forum Against the Oppression of Women staged a demonstration outside the police station in Turbhe, in Navi Mumbai. The women were protesting the complicity of the Turbhe police in the investigation of a rape of a construction worker. A number of them were booked for trespassing, and several newspapers carried headlines about ‘feminist hooligans beating up the police.’ Patel recalled being amused: “My weight was around 40kgs then!”

Then one day, the sentence “All Men Are Potential Rapists” was found painted somewhere on Mumbai’s Marine Drive, and the blame fell on the Forum. Members began to be accused of robbery when they helped victims of domestic violence retrieve their belongings from their marital homes.

The FAOW needed systems and accountability. No one had been writing receipts for the group before; no one had thought it prudent to use carbon paper to make copies for records. “Through trial and error, we realised how we need to create structures and mechanisms so that women’s groups don’t get discredited,” Patel said. It wasn’t just for accounting’s sake: these were the things that would stand between feminists and unwarranted arrest.

n March 1980, the women’s magazine Eve's Weekly produced a special supplement on rape. A banner on the cover read: “It’s time we looked rape in the face.” Inside, there were articles on rape as a means of social oppression and marital rape.

“This would likely have been unthinkable even a few years earlier,” Ammu Joseph, an assistant editor with the magazine at the time, said.

Young feminist journalists such as Joseph and Pamela Philipose, to name just two, found themselves covering a movement in which they were also participants. Joseph said that this dual involvement helped journalists get activists and academics to contribute to media outlets, “which in turn helped get the message of the movement across to the public.”

None of this made consent and agency mainstream issues, even though “many of us did write and talk about it at that stage,” Philipose, who began her career with The Times of India in the 1970s, told me. “It was difficult to break the patriarchal attitude of the newsroom. Editors never saw rape as an issue worth discussing. It would never figure in an editorial, for instance.” The conceptual breakthroughs that the women were making in their own circles weren’t trickling into wider society. “Most people saw it as a fringe thing.”

The work of reaching out remained to be done.

The women made songs, theatre and art. Sonal Shukla, from a family of trained singers, composed songs about women’s feelings and demands. She was thinking of the resistance songs she had grown up hearing, made by the legendary Indian People’s Theatre Association for the Quit India Movement; songs with lyrics like “Jaga re jaga sara sansar / Angadai le ke yeh dharti uthi hai, sadiyon ki thukraai mitti uthi hai.” Awake, the whole world is awake / It rises from its slumber, after centuries of oppression the earth awakes. Another song went “Tod ke bandhano ko, dekho behnein aayi hai, naya jamana layegi”: Our sisters have broken our chains and brought with them a new era. [13]

The life and politics of the movement had altered the lens through which the women looked at their own lives. “Earlier, our definition of patriarchy was very limited,” Datar said.

In Making A Difference, Phillipose wrote that for all the apprehensions that the Forum was “blindly ‘anti-men,’” there were many––including men––who saw its transformative potential. [14] “Women activists perceived it in more personalised terms—as a platform, a network, a shelter of their own, something that everybody could claim but nobody could possess.” It was in keeping with a common theme which became clear across the newly formed women’s organisations which protested custodial rape and sexual violence. All their participants saw themselves as part of national movements.

Momentum

“But what matters is a search for liberation from the colonial and male-dominated notions of what may constitute the element of consent, and the burden of proof, for rape which affects many Mathuras in the Indian countryside”

–– An Open Letter to the Chief Justice of India

Through all this, the one unshakeable demand was the amendment of the rape laws, especially since reopening the Mathura case was off the table. At the 1980 conference in Mumbai, the legal concept of “burden of proof” became an important point of contention. Criminal cases require a complainant to prove that an offence has been committed. Many in the movement insisted that the rape law reverse this, and it became something of a fundamental demand. But trade union activists and Dalit activists resisted. Such a change would make it easy to trump up charges against men from marginalised communities, as well as activists and dissenters. Endemic as sexual violence was in India, so was caste oppression and economic injustice.

In 1983, India’s rape laws were amended for the first time in a hundred years. The Criminal Law (Second Amendment) Act added a new category of offence for custodial rape, and rape by persons in authority. Finally, women had specific legal recourse against being assaulted in jails, remand homes, women’s and children’s institutions, and hospitals. The Evidence Act of 1872 was amended to say that in certain circumstances such as custodial rape, the survivor’s word on non-consent will be presumed to be true. It was then upto the accused to rebut it. All rape trials were required to be held in-camera. It became illegal to reveal a survivor’s identity. [15]

Other demands went ignored. There was nothing to prevent a woman’s personal history from being brought up in the course of a trial. Feminists had agitated for the inclusion of rape “under economic duress” as a separate category, hoping that it would close the loophole that protected marital rape. This was not addressed. It remains a matter of serious contention in 2020.

The women’s movement of the 1980s saw all forms of rape as an act of power. [16] But from the beginning, feminists also contended with the concept of “power rape,” proposing its inclusion in the law as a separate category. In their note of dissent to the Joint Committee on the amendment bill, the Marxist parliamentarians Geeta Mukherjee and Suseela Gopalan defined this as “where a woman is raped under economic domination or influence or control or authority….”

It's hard not to think of endemic caste-based violence against women, which continues to go unacknowledged at every level of government, including the highest, forty years after this definition was first introduced in Parliament.

“After the initial experience we realised that although everyone condemned rape, the reasons were poles apart,” Flavia Agnes wrote in 1993. [17] “For the opposition it was an issue with which to embarrass the party in power as it questions the ‘law and order’ situation. For community organisations, it was a tool to increase their local support and mass base. For the liberals and moralists (the judiciary included), it was a question of ‘violation of her honour and chastity,’ the most prized possession of an Indian woman. The reaction to a rape would change from case to case depending upon the power balance between the rapist, the victim and the community. Hence condemning rapes by police was simpler than taking a position in rapes within class, caste, community or the family.”

What feminists in the 1970s and 1980s achieved was momentum. Never again would the question of women’s issues, gender violence, and inequality be out of the public eye. Violence within families, epitomised by grisly dowry deaths, gained more attention. So did campaigns against sex determination, which preceded sex-selective abortions. The state of Maharashtra, where Mathura’s ordeal occurred, instituted gender-sensitivity training for police officers, and support cells for women in distress. When a second nationwide feminist conference was organised in Mumbai in 1985, the issue of personal laws took centerstage.

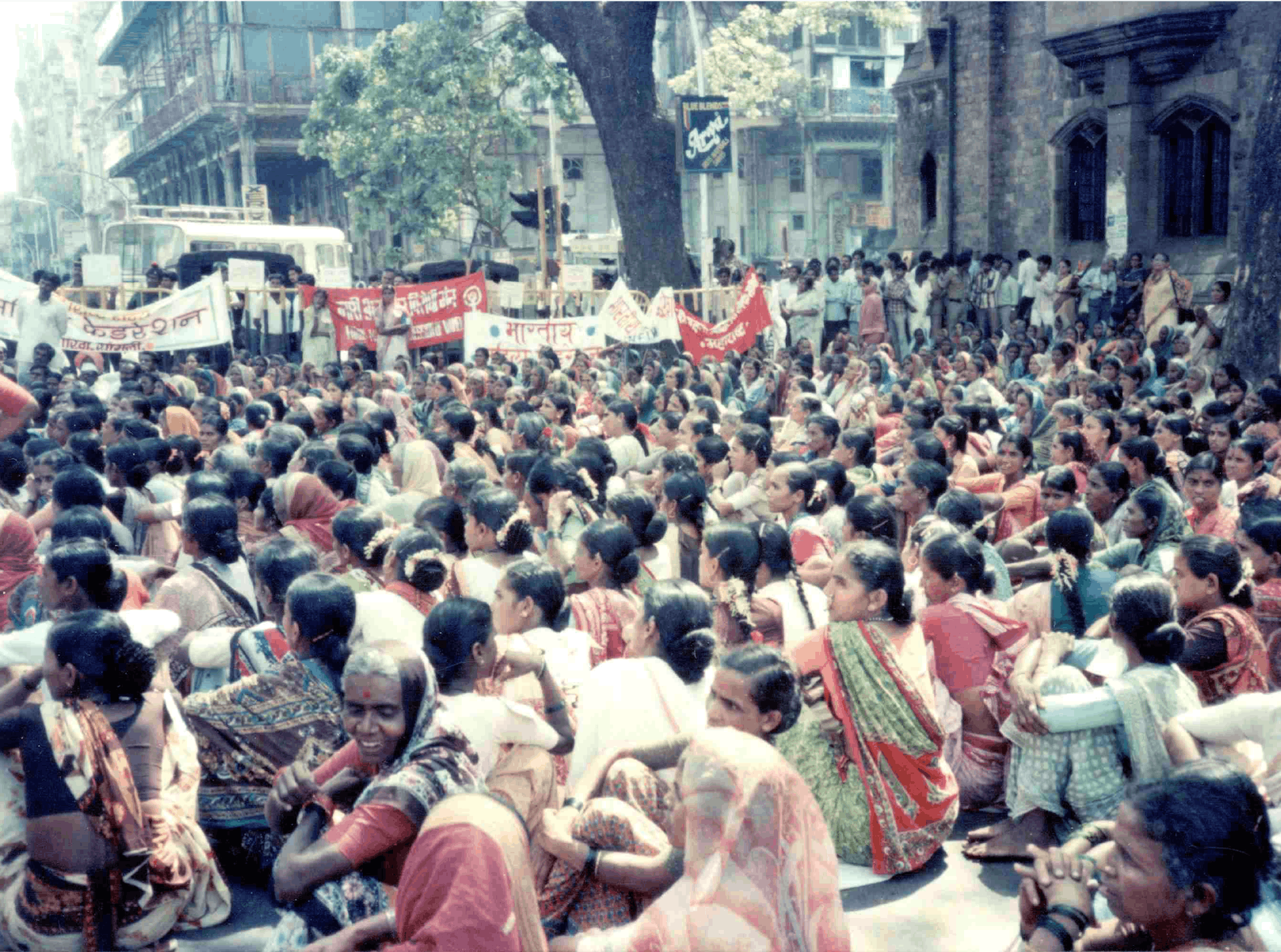

A public meeting to demand reopening of the Mathura case, in Mumbai’s Kala Ghoda area in March 1980. Credit: Vibhuti Patel

After that, the mobilization continued in pockets. There was a broadening in the spectrum of what were considered “women’s issues.” In Maharashtra in 1986, the Shetkari Sangathana, a farmer’s organisation, organised a peasant women’s conference at Chandwad. Around the same time, a large meeting of Dalit women took place in Bhusawal.

Women began to participate in large numbers in the Adivasi movement in Maharashtra, consolidated under the Shoshit Jan Andolan, the ‘movement of the oppressed.’ Ecological degradation linked to dam construction emerged as a big issue. [18] Anti-communalism rallies took place in several parts of Maharashtra. In 1988, large numbers of rural activists went to a women’s conference called the Nari Mukti Sangharsh Sammelan in Patna.

Sonal Shukla went on to found Vacha in Mumbai, a feminist library and cultural centre. Donna Fernandes continues to run Vimochana in Bangalore which now works with female survivors of violence. Vibhuti Patel contributed significantly to women’s studies as an educator at institutions like SNDT Women’s University and the Tata Institute of Social Sciences (TISS). Vasanth Kannabiran started the Asmita Collective, a resource centre and advocacy group for women. Chhaya Datar headed the women studies unit at TISS for many years. Flavia Agnes became a lawyer and founded the Majlis Legal Centre. She is one the country’s best-known practitioners of family law.

“You’re not supposed to know about the women’s movement as some glorious past,” the filmmaker and writer Paromita Vohra told me. Vohra’s work builds on the discussions that the movement began. “You look at it as the history of conversations, as a history of debates, as a history of making mistakes, admitting to those mistakes and learning from them. And a history of people making tangible their imagination of how they want the world to be.”

The energy of that struggle has now scattered. [19] The internet contributes to the feeling of diffusion. On issues like consent and intersectionality, it encourages nuance, but also oversimplification. Social media amplifies many marginal and original voices, but also the illusion of change. The collective nature of the movement that sustained women in the 1970s and 1980s seems unattainable to many. Can this still be called a movement, in the strict sense of the term?

“I do feel that the women's movement exists. Not in the same way, but it’s still existing,” Shukla told me. “And there are debates going on both at the ground level by small groups as well as at the intellectual level. It’s continuing.”

What is a movement?

n The Struggle Against Violence, Chhaya Datar tried to address a fundamental question: What constitutes a movement?

“When one major section of society understands the injustice it has to face and gets ready to change the social structure in a fundamental way, all the activities leading towards it constitute a movement. The movement may not lead towards progressive changes. It could be obscurantist. The essential element is that people participate in it in large numbers. They aspire for change.”

Well, people did. But its successes and failures aren’t recognised as an important source for the way we think and talk about gender, not just in activist circles, but in mainstream media discourse. Without the open letter and its nuanced distinction between “submission” and “consent,” the conversations that became possible in the 2010s would have had no forerunner.

1970s and 1980s feminism was a product of its time, born of the dominant caste and class roots of some of the first responders to gender violence: young women in a young country, having direct and visceral responses to political and economic ferment. We’re now in the age of interiority, encouraged by technology, favoured by the impersonal, even necessitated, now, by a pandemic. Caste and class consciousness is still a work in progress.

“We have a legal system and society that thrives on impunity.”

In 2020, women who continue the dialogue that began nearly half a century ago must account for challenges specific to new ways of life: social media harassment; gaslighting and emotional abuse; sophisticated and manipulative forms of workplace abuse. In some metropolitan circles, the #MeToo movement peeled back the patriarchy and power dynamics that women experience in relationships and at workplaces. By going “beyond the law,” it represented a definite evolution in origin and form. It highlighted patterns of male behaviour—some of which aren’t strictly justiciable in court—and its effects on women and queer people.

But we, too, have been limited by the social position and geography of the women who got to participate in this vital discussion. Beyond big cities and English speakers, complex discussion around consent and sexual violence looks and sounds very different. The fundamental gains women made in fighting custodial rape and state violence remain theoretical for a majority of people. India remains haunted by the ghosts of the 1980s.

“We’ve deluded ourselves into believing that all women are the same and that the category of women is a homogenous category,” Nikita Sonavane, lawyer and co-founder of the Bhopal-based Criminal Justice and Police Accountability Project pointed out. “This is why we are in a situation right now where there are women who cannot identify with #MeToo or any other movement that comes up.”

The feminist scholar Uma Chakravarti believes that there has never really been a strong enough articulation of the fact that all of Indian society is based on the bedrock of a caste-based patriarchy. “We have a legal system and society that thrives on impunity,” Chakravarti told me. “Caste power gives you impunity. Patriarchal power gives you impunity. The state gives you impunity. The academic community gives you impunity. Impunity is built into the way law operates in India. So, in that scenario, what will you do? You’ll have to challenge that.”

In a report published in 1999, Human Rights Watch highlighted a pattern in cases of attacks against Dalit women. The documentation indicated “the use of sexual abuse and other forms of violence against Dalit women as tools by landlords and the police to inflict political ‘lessons’ and crush dissent and labour movements within Dalit communities.”

Seven years later, in 2006, four members of a Dalit family were violently killed by a mob in Maharashtra’s Khairlanji village. Several fact-finding committees concluded that the mother and daughter had been raped repeatedly and tortured in heinous ways after being paraded naked. The rape provisions were not invoked in trial court; nor did the judge consider it a caste atrocity.

The civil rights activist and academic Anand Teltumbde contextualized the crime in his book Republic of Caste. The family had gained a certain amount of economic independence, Teltumbde explained: the children had made academic progress (the daughter cycled to college), and the mother had been assertive in confronting caste harassment. Together, this was considered a violation of the caste norms of the village.

This September, a Dalit teenager was allegedly raped and murdered in Hathras, Uttar Pradesh. It was, among other things, a reminder that we are stuck in a repeating pattern. As the case progressed, the state’s violence was put on display in full glare of TV cameras. The police delayed filing an FIR; authorities failed to ensure adequate medical treatment; and the police burned the body in the dead of night, in the absence of kith and kin.

Until 2014, the National Crime Records Bureau (NCRB) only considered police custody as a category while collecting data for “custodial rape” and reported one case each year between 2011-2013. Since then, it has expanded the “custodial rape” category to include incidents in judicial custody, hospitals, and other institutions. According to the latest report, 47 cases of custodial rape were registered across the country in 2019.

But cases remain severely underreported and improperly investigated. So does custodial violence in general. A spate of startling data was highlighted by the press in the aftermath of the June 2020 deaths of P. Jayaraj and his son J. Bennicks following police torture in Tamil Nadu’s Sathankulam town. Between 2001 and 2018, there have been only 26 convictions in connection with a total of 1727 custodial deaths.

The conversation around consent and state accountability that Indians carry forward today uses a language that became mainstream because of the women’s movement of the 1980s. More recent watersheds, from #MeToo to Hathras, no longer call for amendments. The laws exist, but they are no longer enough. “Nobody has easy answers to this,” Sonavane says. “But the point is to ask better questions, ask complex questions, and involve more diverse voices to truly make the space inclusive.”

”People may not have (a) coherent, comprehensive understanding of the changes they want,” Datar wrote at the end of her attempt to define a ‘movement’ in The Struggle Against Violence. “But leaders do develop a 'world view' about the future society. This ethos encourages people to experiment with cultural practices and helps new value systems to emerge. If this definition is accepted, one would say that the women’s movement has begun.”

Sarita Santoshini is an independent journalist reporting on gender, social justice, and global health & development. You can read more of her work on her website.