This story was supported by the Pulitzer Center.

The Ken is not a long river. Its waters form in the Vindhya Hills of Madhya Pradesh and end at Chilla Ghat in Uttar Pradesh, gliding along for 427 kilometres before pouring into the Yamuna, which is more than three times its length. In the dry season, the Ken can hardly be called a river at all. Its summertime bed is little more than a series of pools that well up from underground. Even in full flow, no one would describe the Ken as mighty or swift. With the sun overhead, its waters harden into slate blue and seem to stop, as though the afternoon light has revealed the river to be no more than a painter’s brush stroke. Black cormorants poke their snakelike necks above the surface, bobbing in place with what appears to be no effort at all. The distance from one bank to the other looks about right for a leisurely swim.

Some rivers are obvious protagonists. The Brahmaputra’s chaotic immensity and the Ganga’s religious importance both demand attention, but the Ken is a kind of quiet backbone, an ephemeral ribbon that carved one of India’s most stunning landscapes and provides a base for one of the country’s wildest ecosystems. Its short length gives life to several villages, courses through a vibrant tiger reserve, and slides down a series of cliffs and gorges that shelter vultures and gharials with little habitat anywhere else on Earth.

People have lived along the Ken since before humans discovered that metal made stronger tools than stone, and the river has provided water to the cities of several kingdoms that have long since eroded. In that time, people have shaped stories about its ebbs and flows. In one of those myths, the Kolahala mountain throttles the Ken until citizens of the Chedi empire’s capital begin to run out of water. The king kicks over a peak, and sets the river loose.

One interpretation of this story is that the mountain was actually a dam that had choked the Ken to a trickle; only after the king ordered its demolition could the river run through the city again. Now, the Indian government has drawn up plans for a dam of its own, called Daudhan. That barrier will be a piece of a larger project that, by some accounts, will do much more than stifle the Ken’s flow.

Surpluses and Deficits

he National Water Development Agency’s ₹44,605 crore-project is called the Ken-Betwa link. The first part of their plan is to level hundreds of thousands of trees in the Panna Tiger Reserve. Then they will build a dam on the Ken, turning this newly barren land into the bottom of an enormous lake. That lake will drain into a 231 kilometre-canal that hooks up to another river, the Betwa, replacing water that the Betwa itself will soon lack due to a planned series of upstream dams. Those dams will serve well-developed but drought-ridden areas around Vidisha in Madhya Pradesh, at the cost of taking water from the relatively impoverished region of Bundelkhand, home to 18 million people, also parched.

“It’s like robbing somebody to pay somebody else,” said Manoj Misra, a river activist and one of several people who have challenged or are planning to challenge the legality of the Ken-Betwa link in the Supreme Court.

“These terms ‘deficit’ and ‘surplus’ are not suitable for natural systems. Surplus means that the natural landscape requires that excess water.”

Delhi justifies its plan, in part, by claiming that Bundelkhand will have a steady supply from the reservoir. The National Water Development Agency also says the Ken has a water “surplus,” while the Betwa has a “deficit.” The water-flow data that supposedly validates this claim is decades old, though even current data wouldn’t suffice, because the concept makes little sense. “These terms are not suitable for natural systems,” said Padmini Pani, a river systems expert and professor at Jawaharlal Nehru University. “We cannot say there is surplus. Surplus means that the natural landscape requires that excess water.”

Drought has starved both rivers. Changes in rainfall have seen them cycle through years of dryness capped by a season of thick downpours and roiling floods, which rush by too quickly to replenish much groundwater.

“It is a huge misconception that this dam, once it is made, will bring water security back to Bundelkhand,” Misra said.

For centuries, technocratic fascination with rerouting rivers has made environmental concerns seem backward and silly. British engineers in India began directing labourers to dig canals across the Gangetic plains in the 1800s, and by the turn of the twentieth century they had started connecting subcontinental waterways to boost irrigation. Some 50 years later, a small group of bureaucrats in the United States plotted to funnel northwestern rivers into mammoth channels that would grow the cities of the desiccated southwest. (The plan stayed on paper.)

Independent India has flirted with a similarly transformative scheme for decades, and the Narendra Modi government is convinced that now is the time for work to begin. The Ken-Betwa link is meant to be only the first of 30 ventures that will regularise the flow of water from Assam to Kerala. Initially proposed by officials in 1982, the National River Linking Project aims to connect 37 rivers and erect roughly 3,000 reservoirs.

The Last Vultures

he thing was squatting off a narrow road, hunched and lumpy, black wings splashed a dirty white, as though another bird had relieved himself from above. His head was shorn and feathers dishevelled, like an eagle with a terrible haircut wearing a rumpled coat. But when he stretched his wings—thrust them once, twice, three times toward the ground—he transformed into an entirely new creature, powerful and light. The man guiding me through the Ken Gharial Sanctuary shouted, “Vulture!” but the bird was already gone, gliding somewhere over the trees.

As recently as the early 1980s, long-billed vultures and their cousins, the white-rumped vultures, were not rare sights. They circled above traffic, stood on street lights, swarmed the dead bodies of goats and cows. Around that time, livestock owners began using a drug called diclofenac to help with the aches of a cow’s last days. The drug stayed inside these city animals even after they died, making its way into vultures when they ate the carcass.

The birds began to drop, littering streets like black bags of trash. More than 99 percent of white-rumped vultures are gone now. In India, around 97 to 99 percent of long-billed vultures have disappeared. Slender-billed vultures, another close cousin, have also vanished. The Indian population of the three species crashed from 40 million in the early 1980s to about 19,000 in 2015. The International Union for Conservation of Nature lists each of them as critically endangered, one rung away from being extinct in the wild.

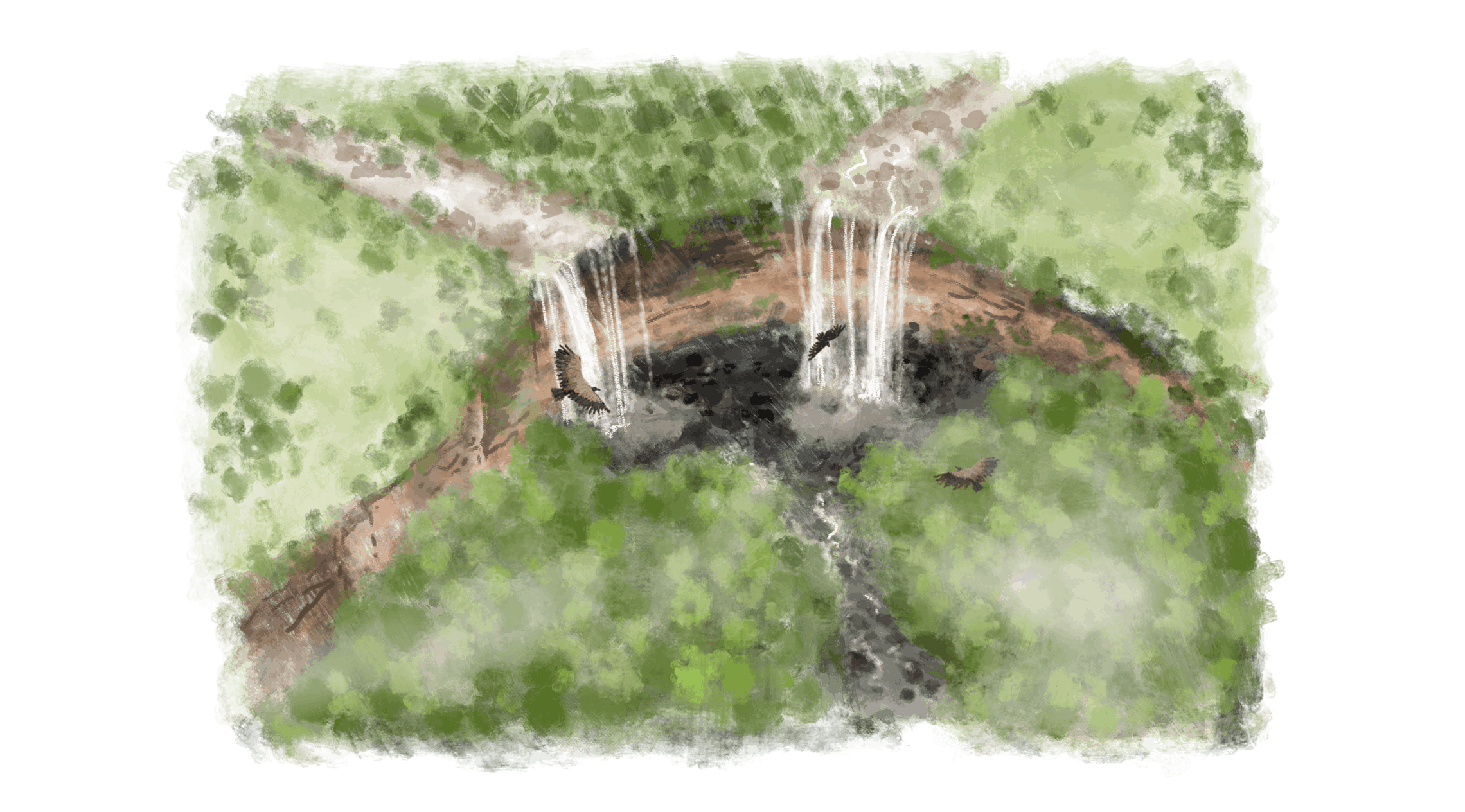

Long-billed vultures and their relatives have found refuge in some parts of the Panna Tiger Reserve. Near a bend in the Ken, around 13 kilometres from the proposed site of Daudhan Dam, monsoon runoff spills over a half-moon cliff called Dhundua Falls, spooling like silk into twin pools. Water sprays back up toward strips of stone that look like layers of chocolate and peanut butter. In the mornings, long-billed, white-rumped, and Egyptian vultures shuffle and shake out their feathers along notches of rock, like commuters fidgeting as they wait for the train. As the day warms, currents lift off the water. After two, maybe three hours of sunlight, the birds drop into open space, riding the rising air in effortless loops.

If the Ken-Betwa link is built, its dam will stand at 74 metres in the middle of the reserve. Water will pool until it drowns the area’s craggy outcroppings, flooding around 50 vulture nests at Dhundua and several hundred more along the river. “That kind of habitat you won’t find anywhere else in Panna Tiger Reserve,” said Orus Ilyas, a conservation biologist at Aligarh Muslim University who has studied the link’s potential impact on biodiversity. “It will be a scattered, fragmented population.”

The birds will fly off as the Ken swallows the cliffs. Some of them will find trees to nest, others might land on a barren hill with just enough ledges. They’ll eke out an existence largely on their own, snapping up what dogs don’t devour, swerving around new power lines that get strung up all the time.

Cotton’s Dream

he statue of Arthur Cotton outside the museum dedicated to him in Andhra Pradesh’s Rajamahendravaram shows an elderly man whose head looks a touch too big for his body. Dressed in a wide-brim hat, suit jacket, bow tie, and holding a cane, he peers out on his visitors with a dour pout.

You’d be hard-pressed to find a Brit more admired in modern India than Cotton, the historian Sunil Amrith wrote in Unruly Waters. Born in England to a family of 11 children, he took a surveyor’s job with the East India Company’s Madras Engineers in 1819. By the 1840s, he was re-engineering the subcontinent’s waterscape, restoring a dam at Kallanai along the Kaveri River and building another across the Godavari at Dowleswaram.

Cotton and his contemporaries came from an island nation where rain fell on days it was supposed to fall and the routes of rivers were as unchanging as the monarchy. India was not like this. Northern rivers scooped up enormous amounts of silt as they rolled down the Himalayas, dumping it at random and forcing the water behind to lash off in a different direction. Riverbeds that were little more than scorched dirt in one year could shapeshift into inland seas after a season of never-ending storms.

The British were in India to make money as quickly as possible, which meant shipping goods with machine-like efficiency and irrigating “wasteland” that could be turned into taxable farms. The subcontinent’s mercurial waterscape did nothing to help with these missions. “Taming the river, which could also stabilise India’s revenue prospects, symbolised the colonial empire’s might,” Arupjyoti Saikia, an environmental historian and author of The Unquiet River, wrote to me in an email.

It was Cotton’s rival, Proby Cautley, who gave the colonisers the symbol they craved. Beginning in Haridwar and stretching more than 1100 kilometres when it opened in 1854, the Ganges canal was the “largest of its kind in the world,” but Cotton’s ambitions were still more profound. He dreamed of linking the Himalayan rivers with the waterways of the Deccan plateau, a seamless, mechanised waterscape that would forever alter life on the subcontinent.

Versions of that vision have also fascinated Indian politicians for generations. In 1970, K.L. Rao, an irrigation minister favoured in his time by Jawaharlal Nehru, was working on a plan to connect the Brahmaputra and the Ganga with rivers in the south. During a speech in 2002, then-president Abdul Kalam said that a project such as this could stabilise the country’s water supply. Within months, the Supreme Court issued a direction to the government to see how it might work. In 2018, speaking before a group of students at the Smart India Hackathon, Prime Minister Narendra Modi talked about how India is constantly threatened by the twin disasters of flooding and a lack of water.

“If there is inter-linking,” Modi said, “the problem can be solved.”

Crouching Tigers, Hidden Gharials

ight of us were sitting in a jeep overlooking the Ken when our guide got a call. There was a tiger nearby. Suddenly we were swerving around turns and ploughing over chunky stones as we clawed our way uphill. We stopped at the crest. Everyone stared into the thicket of brush and teak. Our guide got on the phone, made some inquiries. “Someone heard growling,” he said.

The forest was too quiet; no cawing peacocks or deer honking in terror. “Growling,” our guide said, reminding us. Silence. Minutes passed. Then, like a trumpet blast, a sambar deer called. Everyone whispered. “Tiger, tiger,” the driver said, pointing at where it should be. Again the trumpet blast. We forced our eyes wide. More minutes passed. Our guide looked down and started fiddling with his phone.

Who knows, maybe there had been one lurking around. Panna’s tigers have made a comeback because there is enough room and food to carve out individual territory, and they have no reason to show themselves. The park had no tigers 14 years ago, but after seven of them were released there from 2009, the reserve now has more than 70. “Many people wonder what is the magic that happened with Panna,” said R. Sreenivasa Murthy, the park’s former field director. “The magic that happened is we had a very secure area and they procreated.”

Miles downstream from the tigers, in the Ken Gharial Sanctuary, the river slices through a canyon that rises grey out of the water before brightening into sun-baked colours. Just beyond Raneh Falls, this stretch of river belongs to crocodiles and their cousins, gharials—alligator-like reptiles with snouts that look thin enough to wrap a fist around. On a winter afternoon a couple months ago, half a dozen crocodiles were draped over smooth boulders that curved out of the water, looking like wet laundry tossed outside, their mouths open like expectant baby birds. The gharials—something like two dozen of the world’s estimated 800 in the wild—were nowhere in sight.

Gharials are like long-billed vultures in that the Ken provides one of their last habitats on the planet. The adults eat only fish, and the river hosts a steady stream of carp, mahseer, sucker fish, and other species. Park officials reintroduced gharials to the Ken in 2007 and once more in 2019, when they released 20 females and five males, hoping they would breed on their own this time.

“We have spent so much money for translocation of tigers. Whatever we have saved, whatever we have developed, we are going to destroy all these things.”

If the Ken-Betwa link comes to fruition, the government’s cultivation of gharial and tiger habitat will appear pointless. “We have spent so much money for translocation of tigers,” Ilyas said. “Whatever we have spent, whatever we have saved, whatever we have developed, we are going to destroy all these things.”

The link’s reservoir is likely to entomb the park’s core tiger habitat. According to Ilyas and Murthy, the deer will scatter as soon as the lumber trucks roll in. The tigers will follow until it becomes clear that the reserve’s outskirts don’t have enough space to support them. “They’re all going to lose their places moving this way and that, disturbing settled tigers in other areas,” Murthy said.

Many reserves across India are connected by ‘wildlife corridors’—protected woodland highways that allow animals to cross from one park to another without bumping into people or cars. To compensate for the area the reservoir is expected to submerge, the government has said they will link Panna with the nearby sanctuaries of Nauradehi, Ranipur, and Durgavati. This was confirmed to me by Bhopal Singh, the director general of the National Water Development Agency.

So far, the corridors exist only on paper. Even if they come to pass, those woodland highways won’t prevent the gharials’ stretch of the Ken from thinning to a creek. The reptiles have already suffered from reduced water velocity caused by farming and sand-mining. Maybe, as the river shrinks, they’ll be forced to spend more time in view of the tourists, searching for any carp or mahseer that manage to splash their way out of the new reservoir. For a while, it could seem like there are more gharials than before.

Pipe Dreams in the West

ike the British in India, engineers in the United States were enthralled by how their ideas and the labour of others could transform their country’s rivers. In the first half of the twentieth century, the US was trying to grow cities such as Phoenix and Los Angeles across an enormous dusty plain, and a group of secretive technocrats thought dams alone weren’t up to the job.

One of them was Mike Strauss, a former journalist from Chicago who’d married into a family that owned an island off the coast of Maine and who’d elbowed his way into leading the Bureau of Reclamation. Another was William Warne, who was horrified by deserts and outraged by rivers that spilled unused into the Pacific. Stanford McCasland, the third member of the trio, had moved from the US to Colombia in search of giant rivers he could wrangle into routes he found more suitable. The three of them came together to spearhead the United Western Investigation, a planned series of continent-warping river diversions that the author Marc Reisner called “the best-kept secret in the history of water development in the West.”

The basis of the plan was to take “surplus waters of the Northwest” and pour them into “water-deficient areas elsewhere.” They thought about channelling northern waterways through mountains, piping them along the ocean floor, diverting them around hills, and using gravity to funnel the water south into California through a combination of tunnels and aqueducts.

If the engineers had written up their ideas a decade earlier, some of them might have come to pass, but by the mid-1950s, big works of water engineering were falling out of favour in the upper echelons of US government. Plus, McCasland was driving the plot. According to Reisner, he was too much of an asshole to make nice with everyone who might help him reshape half the country.

Their plan wound up shelved in a small bureau office in Salt Lake City. Now, its spirit is being revived in a country some 12,000 kilometres away.

Marking Territory

havna Kumari lives along the river she’s trying to save, just a few kilometres from where it enters the park. The Ken glides below the ₹15,000 per night lodge she runs with her husband, Shyamendra Singh, the grandson of a local prince. Just after noon on a recent Wednesday in January, she walked up to the entrance calling after her black and brown wiener dog, Chubby, who was barking obligatory warnings as he waddled up to a small group of intruders.

Kumari is from Himachal Pradesh but has lived along the Ken for more than three decades, and she got wind of the river-linking project nearly 10 years ago. Not long after, she, along with her husband and a group of villagers from nearby Madla, showed up uninvited to a meeting that irrigation officials were holding in a village called Silon that was in line to be submerged.

Person after person spoke seemingly rehearsed lines about the good the project would do for the area around the city of Panna. When Kumari tried to speak, it was impossible for anyone to hear her over the drumming coming from men who seemed to be with the irrigation department. When the drummers stopped, others shouted over her.

To residents of the 10 villages that the project will put underwater, this was suspicious. Most of them didn’t know anything about the Ken-Betwa link—officials hadn’t bothered to mention that they were going to be evicted, several people told me—but now they wondered why no one had been allowed to debate the plan’s merits.

“Even the Britishers didn’t behave in the manner that the government and their officials are behaving with those whose homes are being ruined,” wrote Amit Bhatnagar, a Panna-based activist, in a recent letter to the government that he drafted with protesting villagers who then marched it to the local collector’s office. “We will not tolerate the killing of constitutional rights.”

Word of the project began to creep through the towns of Ghughari, Kharyani, Palkoha, and others. Kumari started speaking about it to whomever she could. Government types marched into Panna Tiger Reserve and plopped down a red concrete stump meant to mark the centre of the future reservoir. Kumari and other locals—many of them work as informal labourers, others raise cattle—protested in front of the district headquarters in Panna.

Sometime in 2017, four men checked into two rooms at Kumari’s resort to demand that she keep quiet.

“You don’t know who you’re dealing with,” they told her.

“Tell them they don’t know who they’re dealing with,” Kumari replied.

The squabbling settled into a stalemate for years, but the work now seems to be gathering momentum. In December last year, villagers in the reservoir area discovered sheets of paper stuck to the walls of their homes—eviction notices written in Hindi, a language many of them can’t read. The letters gave residents 60 days to get out, but no guidance on where to go or how to get there.

The villages in the flood zone are in and around the park, often kilometres away from any main road, and no one owns a car. Now, some residents have begun to publicise a list of concessions that they want from the government before they’ll consider moving: ₹30 lakh per voter, irrigated land or equivalent compensation, plots for those who don’t own any.

Tanks Running Empty

n paper, the Union government can argue that the benefits of the Ken-Betwa link outweigh whatever will be lost. Bhopal Singh typed them out for me unprompted after I asked about something else: irrigation for one million hectares across two states; drinking water for 6.2 million people; 103 megawatts of hydropower. “This project will definitely bring economic prosperity to this backward area due to increased agricultural activities,” he wrote, reproducing—verbatim—the justification in the Ken-Betwa link project report, published in 2010.

Singh claimed that farming will flourish in Bundelkhand once the link is complete, but Seema Ravandale, an infrastructure researcher at the People’s Science Institute, told me that irrigated land around the canal will likely extend just a kilometre on either side. Farmers will only pump two to five inches of water through their fields, which is enough to wet the topsoil but far too little to replenish the groundwater there or anywhere beyond. Once the entire project is finished, the only districts that are likely to end up with more water are Bhopal, Vidisha, and the surrounding areas that will benefit from the new dams along the Betwa. That region is nestled in Bharatiya Janata Party heartland and is already far more economically developed.

“Tank irrigation would not be sufficient for ensuring the water security in parched regions of Bundelkhand.”

The Modi government is facing many more problems from droughts, floods, and heat waves than its immediate predecessors. The desire to find a one-off fix is understandable, but the mechanised solution proposed by the National River Linking Project will have massive, unforeseeable consequences that may well magnify India’s climate problems rather than make them manageable.

There is already some evidence for this. According to Subimal Ghosh, who co-authored a paper about river-linking’s potential impact on regional climate, there are way too many variables to predict how manmade lakes and shifting rivers will affect what happens in the clouds, but there are signs that more irrigated land could mean less rain. Irrigation cools the atmosphere, which often leads to low clouds that provide little more than shade.

If the Union government wanted to give Bundelkhand some water stability, Ravandale told me, it could revive the decrepit tanks found across the region. Singh wrote that he believes this kind of irrigation “would not be sufficient for ensuring the water security in parched regions of Bundelkhand” but Ravandale has seen it work. She knows farmers who have irrigated their plots by digging talabs—ponds—that cover about 10 percent of their land.

I didn’t see too many animals in Panna. No tigers, no gharials, not even any langurs. Animals living in the reserve have enough space to spend their days away from camera-toting tourists, but if the Ken-Betwa link is built, the silence that surrounded me might become permanent. The park may well turn into another lifeless landscape, emptied of the tigers, gharials, deer, and people who live there. Beyond it, Bundelkhand will shrivel up gradually, until there is nothing left to squeeze out of the ground.

Colin Daileda is a freelance journalist in Bengaluru, India. He has written for Atlas Obscura, Longreads, The News Minute, and many others, and has lately been writing about humanity’s often confrontational relationship with water. When he is not doing that, he is maybe playing basketball or eating a doughnut.