The history of Delhi is replete with instances of events that have changed its character almost overnight. These include plunders, agitations, coronations, assassinations, all driven by the machinations of men and women.

The history of Delhi is also a story of climate change. The city’s natural environment has changed more deliberately than its social and political character, and these transformations have been starker still. The Yamuna has altered course. The vilayati kikar has almost cannibalised the city’s native vegetation. A dystopian smog now has an annual chokehold over the early winter months. Short-sighted human decisions have played their part in these changes. They’ve always been made with a poker face, as if to exonerate our species of all accountability.

There’s one natural disaster that few in the city now remember. It arrived with the force of a gale and disappeared before people knew what hit them. Forty three years ago, a tornado ripped through the university campus in north Delhi, killing 28 people and injuring 700 others.

Maybe it’s been erased from public memory for sheer absurdity. It is difficult to believe such a thing ever happened there. It came, it destroyed, it left. Timur the Lame did the same in his fourteenth century sack of Delhi. Historians of medieval India have analysed the Mongol invasion minutely for its impact on the teetering Delhi Sultanate and the fate of the city’s citizens. We aren’t yet in the habit of framing climate events in similar ways.

Here is a closer look at the freak tornado of 1978, and how it changed those who encountered it. For witnesses, such as the writer Amitav Ghosh, it induced a new respect for the elements and transformed their relationship with the weather. For those who read about it, it was a lesson that the climate has always been capable of change. For present-day citizens of the capital, living on the brink of an ecological crisis, it is a reminder of something we often find ourselves saying to each other: “Mausam bilkul badal gaya hai pichle kuch saalon mein.” The weather has completely transformed in the last few years.

he seventeenth of March 1978 began like any other day. It was a Friday. People were milling around the university campus in north Delhi, which lies between the thorny forests of the Ridge [1] and the stagnant waters of the Najafgarh drain.

The part of the city popularly called North Campus is a sprawling criss-cross of tree-lined roads, leaf-shaded lanes and century-old colleges. While the front of the campus is neatly demarcated by the Mall Road, its southern end is occupied by Kamla Nagar, a densely-packed maze of restaurants, bookshops and clothing stores. Running down its centre and connecting the two is Chattra Marg, home to several colleges and postgraduate departments. Either side of Chattra Marg is flanked by neighbourhoods made up of a mix of residential buildings, commercial establishments and student accommodation.

On that day, as afternoon turned to evening, students were returning to their hostels, heading to the library or gravitating towards the many tea stalls. The weather was moody: thunderstorms were breaking out over different parts of the city. The sun had been eclipsed by dark clouds and the campus even saw a bit of hail. But none of this was out of the ordinary for Delhi in March. In fact, the cool breeze and the scent of rain made for a welcome change as my mother stepped out of the Central Library and made her way to the Arts Faculty building.

ive years earlier, Delhi University had established its first hostel for women enrolled in postgraduate and research degrees. In 1977, my mother Rasham Adlakha moved into a room on the first floor as a master’s student at the Shri Ram College of Commerce. Lectures were long and often stretched late into the afternoon. As one of two women in her batch, my mother was aware of the expectations that rested on her, both here and back home in Nehru Colony, Gurgaon, where my anxious grandparents awaited her phone call every evening.

She had developed a routine of heading straight to the library after classes ended. That day in March was no different. Despite the dreary weather, she ate a quick lunch at her college canteen and walked across the road to the Central Library. Rows of DU’s signature grey metal library shelves sheltered her and other students from the world outside, towering over any window that could have offered a glimpse of the brewing storm.

“There was this statue in the lawn of the founder of the college. It just came out of the ground and toppled over, pedestal and all.”

A short walk away, Dr. Suroopa Mukherjee was in the Hindu College staff room, going over her notes for a workshop she was scheduled to take at Daulat Ram College. The staff room buzzed with chatter about the weather’s turbulent turn. Should the professors advise the students to go home? Some of the other colleges, it seemed, had already done so. The rain was falling in short, sharp squalls and a thunderstorm seemed inevitable. But Mukherjee’s mind was firmly on the workshop. It was going to be one of her first panel discussions as a representative of Hindu’s Department of English. Gathering her things, she left the staff room and began making her way to the Daulat Ram campus two streets away.

The weather seemed to worsen with each step she took. By the time she reached Daulat Ram, the wind was howling through the trees. It is the clouds she remembered most vividly. “They were unlike anything I’d ever seen, they were almost unnatural,” she told me. Most colleges in Delhi University are infamous for their rows and rows of classrooms that seem to defy organisational logic, and she was still searching for the right room when a security guard told her the workshop had been cancelled. The college had sent everyone home. In the dim light, Mukherjee made her way back onto the main road and started looking for an auto that could take her back to Vikram Nagar, where she lived at the time.

For some, the campus was home. Today, Navtej Sarna is a retired diplomat and prolific author. Then, he was a resident of Delhi University’s Jubilee Hall hostel. On a phone call, he recalled the precise moment the pleasant breeze turned into something sinister. “There was a debate at SRCC. I had just come out of the building with a friend and one of the judges, Professor Vineet Chaudhuri,” he said. “Looking towards Kamla Nagar, we saw this thing coming down the road. Professor Chaudhuri used to wear heavy glasses and, the next thing we knew, they flew off his face and hit the gate.” Sarna’s party ran back into the college and lay down in the corridor, grabbing onto pillars for support.

“Everything was flying. There was this statue in the lawn of the founder of the college,” he remembered. “It just came out of the ground and toppled over, pedestal and all.”

ewind a few minutes. Unaware of the dangers that lay outside, my mother had made her way out of the Central Library and onto the road. She walked straight into the path of the first tornado in Delhi’s recorded history.

A dark, swirling funnel of air had appeared out of nowhere. She stood rooted to the pavement as it spun steadily in her direction. After erupting in Roshanara Garden and ripping through Kamla Nagar, the tornado had spun towards Chattra Marg, the spine of the campus. A student appeared out of nowhere and grabbed my mother’s hand. He sprinted to the left and made a beeline for the Delhi University Student Union (DUSU) office, less than a hundred metres away. My mother snapped out of her shock and followed him, but not before she caught sight of the whirlwind ripping the door off a passing cab and carrying it away.

Dozens of students crowded for shelter inside the DUSU office. My mother remembered the anxious silence within and the piercing sound of the wind outside, punctuated by loud crashes and sudden bangs. Transmission lines were breaking off with a snap. Trees heaved and groaned as they were pulled out by the roots, leaving yawning gashes in the sidewalk.

Rajesh Kapoor, freshly graduated from high school, was standing at the window of his family’s fourth-floor apartment on Probyn Road, less than 500 metres from the campus, when a giant tin sheet went flying past. Aghast, he watched as more and more objects were carried off by the furious winds. On most days, two All India Radio transmission towers and a row of dense trees blocked his view of the Mall Road. Within seconds, however, the tornado had levelled everything in the way, giving Kapoor and his brother a clear view of the chaos it would leave behind.

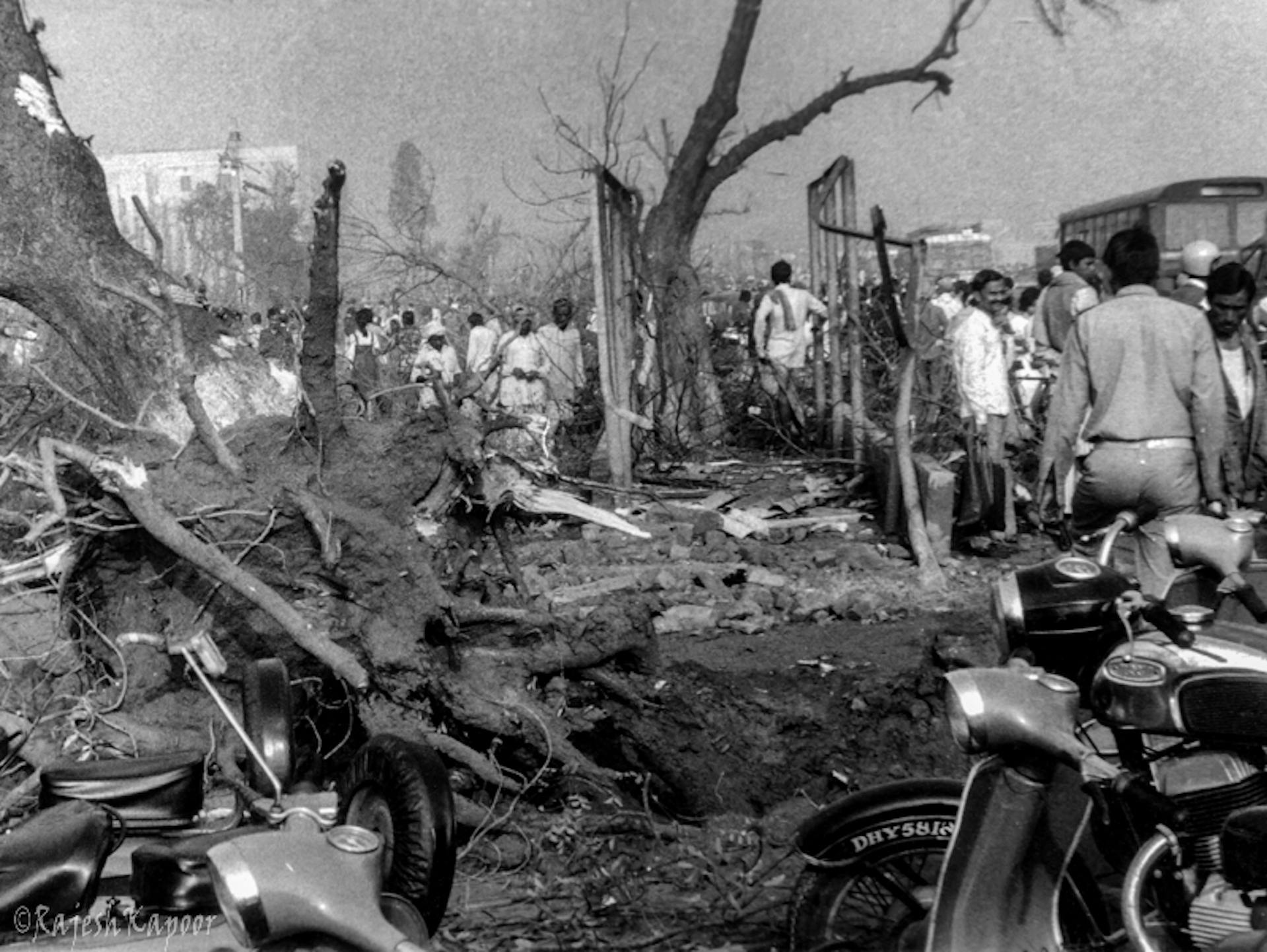

As the storm cleared, Kapoor remembered, dozens of injured people were put into passing vehicles and rushed to nearby hospitals. It is common for people to take shelter at bus stands or under the trees to protect themselves during Delhi’s andheris or dust storms.

On that day, however, it would prove to be a mistake. People crowding in bus stands and under trees were hit by falling branches and flying debris. As the Kapoors rushed out of their apartment to help the injured, they saw the transmission towers lying crumpled on the ground.

n 1978, Amitav Ghosh was a student of Anthropology at Delhi University. Like most master’s students, he spent a chunk of his time in the library. That day, however, noticing that the weather had taken a turn for the worse, he decided to head back to his place through the Maurice Nagar intersection, a route he normally never took, and one that led him towards the tornado. In The Great Derangement, his 2016 book on climate change, Ghosh recounts witnessing the exact moment the tornado formed:

Glancing over my shoulder I saw a grey, tube-like extrusion forming on the underside of a dark cloud: it grew rapidly as I watched, and then all of a sudden it turned and came whiplashing down to earth, heading in my direction.

He had to think fast. The closest shelter was an administrative building of the University. Finding its glass-fronted entrance overwhelmed by cowering students, Ghosh quickly jumped into a nearby balcony, crouched on the floor and covered his head. The eye of the storm reached him in a few seconds. As the wind rose to a frenzied pitch, it began pulling and tugging at his clothes as he pressed himself closer to the ground.

A whirlwind of dust churned above him. It carried a medley of objects the tornado had plucked—lamp posts, bicycles, bricks, water coolers, laboratory equipment, an entire tea stall. And then, just as suddenly as it had appeared, the tornado dissipated. An uneasy stillness fell over the campus.

The glass entrance of the administrative building had shattered under the tornado’s force. Several students were bleeding. The road Ghosh had been walking was completely transformed: trees were lying on their side, telegraph poles were twisted out of shape, entire walls of brick-and-mortar had been blown out. The campus was in darkness—the tornado had ripped through the power lines.

It was into the dark that my mother, steeling her nerves, stepped out from the DUSU office. She crossed the battered landscape of North Campus on her way to the hostel, making her way around fallen trees and occasionally hearing the crunch of broken glass underfoot. The girls in the hostel were miraculously unscathed: shattered window panes and minor injuries, but no fatalities. None of the phone lines were working. Cut off from the world outside, the girls passed the long night huddled together in their rooms.

n the morning of 18 March, Rajesh Kapoor ventured out of his flat with his camera.

His black and white photographs of the aftermath depict scenes straight out of a disaster movie: a car flat on its back like a poisoned bug, a bus that flew off the road and into the garden of Khalsa College, an entire bus stand levelled to nothing. Campus residents can be seen milling about these carcasses. Some are trying to figure out what to do, others are just taking it all in. My maternal grandfather might have been somewhere in this crowd of bewildered faces. As soon as the news reached him, he had rushed to the University to bring my mother back home.

“A car flat on its back like a poisoned bug.” Courtesy: Rajesh Kapoor

“One image which is etched in my mind is of the Miranda House College building, on the side facing Khalsa College, where the road-facing wall was totally blown out,” Kapoor told me. “From the road, I could see the innards of the room on the first floor with twisted fans hanging from the ceiling.”

Further down the road, Navtej Sarna was also clicking pictures of the devastation. One shows a hastily scribbled signboard outside Miranda House college, informing students that classes for the day stood cancelled.

By this time, the media had shown up as well. A TV station was interviewing survivors and eye-witnesses. One man, Kapoor remembered, was recounting how the wind had physically lifted him up. The man had tried to grab the door handle of an Ambassador parked nearby, but the tornado had simply ripped the handle off and him along with it. It then sent him flying through the air, depositing him 20 feet away. (Such cross-depositing is a common feature of tornadoes around the world. Often, flying debris can cause as much damage as the twister itself. Sarna mentioned how a motorcycle on Mall Road had found its way to the rooftop of Khalsa College. A soft drink kiosk at the Arts Faculty was found, crushed like a can of soda, 500 metres away.)

For the witnesses, one question remained unanswered: what had that been? It was certainly nothing like any storm they had seen. It wasn’t until the next day—the 19th of March—that the newspapers found the right word for it, courtesy the meteorological department. One man from the department, in particular, would become the chronicler of the event.

H.N. Gupta was Chief Forecaster at the Meteorological Office at Delhi’s Safdarjung Airport, 14km south of North Campus. On 17 March, his team had been monitoring the capital’s weather conditions as a matter of routine. And though they had noticed a low pressure area forming over the north-west of the country, they thought the worst of it would be a thunderstorm. But by 6:30pm that evening, it became clear that something altogether different had occurred. That is when Gupta set out for north Delhi.

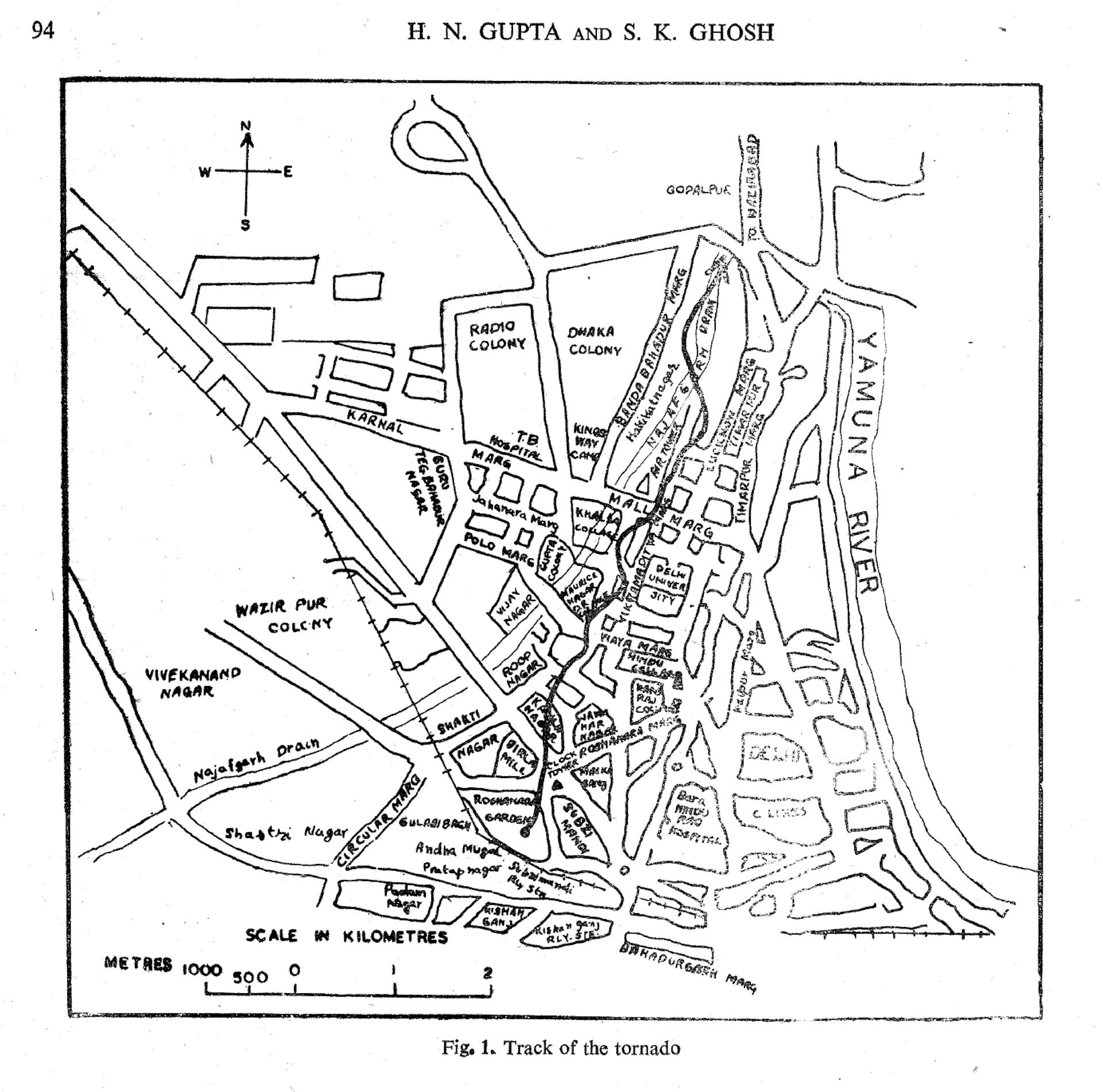

The result of Gupta’s observations was a paper on the origins and path of the Delhi tornado. It was co-authored with his colleague S.K. Ghosh and published in Mausam, the Indian Meteorological Department’s quarterly journal, in 1980. It is the most detailed account of the tornado available today.

The paper notes that the tornado was the result of two thunderheads (towering storm clouds packed with water vapour) from the south colliding somewhere near Roshanara Bagh, a seventeenth century Mughal garden.

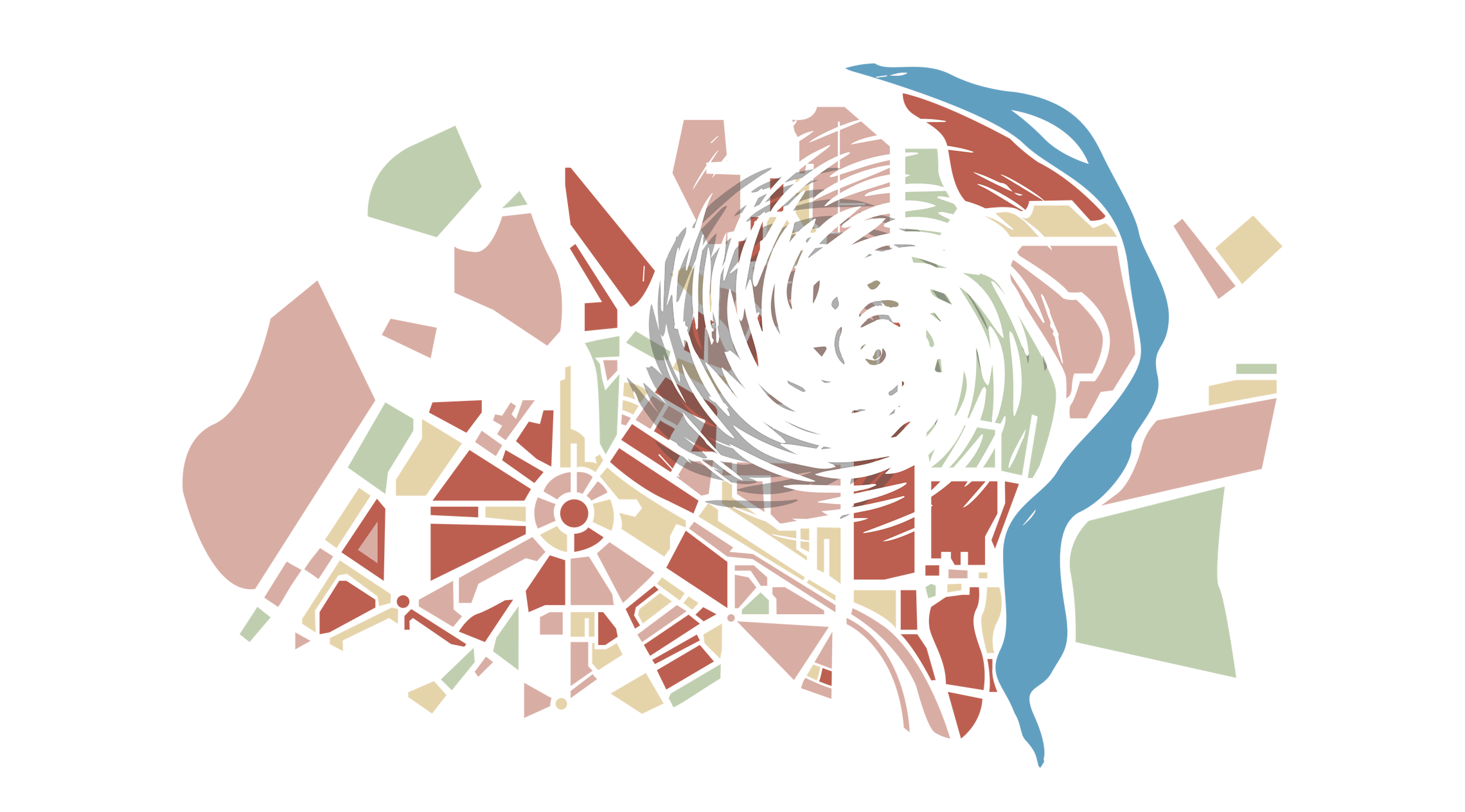

In Gupta’s meticulously-labelled map of North Campus, an unsteady black line cuts through the landscape, denoting the tornado’s path.

The resulting tornado began its rampage from the Roshanara Fire Station, where it forced a fire engine out of the shed and dashed it against the Police Station. Gupta then goes on to offer a blow-by-blow account of the damage caused at each of the twister’s pit stops. The south side of the Kamla Nagar Clock Tower lost its glass and both hands; the boundary wall of the Birla Higher Secondary School was toppled, killing a student; three buses were knocked onto their backs near the Maurice Nagar intersection; 12 were killed when the military barracks on Probyn Road collapsed; a private bus with 70 passengers was plucked off the Mall Road and deposited into a nearby nullah, killing two people. Total damages amounted to more than ₹1 crore.

Accompanying the detailed survey is a hand-drawn map of the tornado’s trajectory. The antecedent of the cartographic exercise may have come from closer home than the authors may have realised. A study published by the Indian Institute of Tropical Meteorology, Pune, in 2019 claimed that the first person to document a tornado’s path was an Indian scientist. In 1865, Babu Chunder Shikur Chatterjee was an employee of the Surveyor General of India. That year, he published a paper titled ‘Note on a whirlwind at Pundooah.’ It documented the path, scale and rotation of a tornado in Hooghly, West Bengal.

The authors build on the format Chatterjee used. In their meticulously-labelled map of North Campus, an unsteady black line cuts through the landscape, denoting the tornado’s path. Ghosh and Gupta’s research would prove invaluable to later meteorologists researching tornadoes in the subcontinent. The map couldn’t help me find a way to them: Ghosh has since passed away and calls to Gupta’s purported landline went unanswered. But it did lead me to another expert who could answer my questions.

The map published with the article in ‘Mausam,’ the IMD’s quarterly journal. Courtesy: H.N. Gupta, S.C Ghosh, under Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International License

n my search for Gupta and Ghosh, I came across the work of S.C. Bhan, a scientist at the India Meteorological Department, New Delhi. Bhan specialises in operational meteorology, the technical term for weather forecasting. In 2016, Bhan and his colleagues at Mausam Bhavan published a meteorological analysis of tornadoes over north-western India and Pakistan. The paper compared data for 15 reported cases of tornadoes in the region over a period of 110 years. Interestingly, half of these occurred in March alone. What is it about March and tornadoes, I asked Bhan after I managed to track him down.

Tornadoes are what meteorologists call a meso-scale phenomenon: weather events that take place in areas that are too small to show on the sweeping weather maps that you see on the evening news. Typically, a tornado is a contained event. It occurs in a very small area over a very short period of time. In fact, as Bhan told me over the phone, the weather conditions that cause a thunderstorm are the same conditions that cause a tornado.

In India, the period from March to June is known as the pre-monsoon. During this time, air in the lower atmosphere becomes warm and moisture-laden. The Arabian Sea is at its warmest and the westerly winds blowing over it often cause weather disturbances in the north-western part of the country.

Over 30 minutes, Bhan took me through the basics of a thunderstorm. The science is relatively simple: the increase in temperature causes the air near the surface to become warmer because of which it starts rising, forming what is called an updraft. As it rises and reaches cooler temperatures, the water vapour in the updraft begins to condense and forms a cumulus cloud. The cloud gets denser and darker as more water droplets form and more condensation occurs, releasing even more heat inside the cloud.

Eventually, however, the updraft of warm air is no longer enough to hold the water. This creates a downdraft: the technical term for the rain and cool air that begin to descend from the cloud. The combined cycling of the updrafts and downdrafts causes the cloud to expand into a cumulonimbus cloud or thunder cell. Lightning and thunder usually begin at this stage.

In most cases, a thunderstorm’s downdrafts eventually outpower its updrafts and it begins to dissipate after anywhere between 20 minutes to an hour of rain. Occasionally, however, if the winds in a small geographical area vary sharply in their speed or direction, [2] the updrafts of air inside the storm cloud begin to rotate at high speeds.

Bhan explained that this rapidly rotating horizontal funnel of air is what is called a mesocyclone: a cyclone trapped inside a cloud. In some cases, a continuing updraft can push this horizontal mesocyclone and tip it over into a vertical funnel which starts sucking up more warm air from the ground. In rare instances, this funnel cloud continues to grow vertically. Eventually, it touches the ground to become a tornado.

When meteorologists looked back, they realised that the weather conditions on 17 March ticked precisely these boxes. [3] Low atmospheric pressure had been building across the northwest and wind speeds had been unusually erratic over Punjab and Delhi.

ore outlandish theories about the provenance of the day’s extraordinary events exist in Delhi folklore. One of them can be found in author and journalist Sam Miller’s book about the city, Delhi: Adventures in a Megacity. Its source is Professor S.K. Trikha, a former professor of astrophysics at Delhi University. Trikha believed that the tornado was actually a visit by an Unidentified Flying Object (UFO):

[Trikha] told me how he had walked around on the DU campus on the evening of the devastation with his own Geiger counter, and the highest levels of radioactivity were precisely those that had suffered the most damage. He believes this could have only been caused by a nuclear-powered aircraft, spinning on its central axis so as to hover ten feet above the ground. Because it was spinning, it created a vacuum which sucked up everything beneath it, and its directional nozzles[...]were responsible for slicing off the tops of the trees.

There are no other mentions of Trikha in the literature around the Delhi tornado. Despite multiple attempts, I was unable to find a way to contact him. Miller also mentions a second theory from a book by the historian and journalist R.V. Smith. [4] In The Delhi That No-One Knows, Smith wrote about a trio of ‘tornado graves’ outside the Defence Institute of Fire Research on Probyn Road. [5] The Institute was among the last places the tornado visited in its marauding path.

The story goes that the land on which the Defence Institute is built used to be the headquarters of a colonial cavalry regiment called Probyn’s Horse, commanded by British officer Dighton Probyn. In 1947, when the country was partitioned, Probyn’s regiment, comprised largely of Muslims, was allotted to Pakistan. The regiment packed up its belongings and made the move. The only thing left behind was the grave of a pir who had been buried at that spot along with his wife and son.

To atone, the panicked contractor immediately built a replica of the three graves under a tin shed. It remains a part of the Institute compound today. Every Thursday, local devotees and Institute employees visit the shrine to pay homage to the pir and keep future tornadoes at bay.

hese alternate explanations may read straight out of a work of fiction, but so does the event which inspired them. In their recollection, every eyewitness I interviewed used words like “unbelievable,” “unimaginable,” and “absurd.” Ghosh himself repeatedly grapples with improbability when describing his experience in The Great Derangement. (The book is dedicated to the Delhi tornado.)

The events of that March evening had no connection to globally rising temperatures. Even today, scientists do not believe there is any conclusive evidence linking global warming, and a warmer planetary climate, with more frequent tornadoes. But the tornado is important because it ruptured people’s sense of familiarity with the weather.

The tornado forced city-dwellers like Ghosh, seemingly immune to climate catastrophe, to face the fact that some moist air and a few winds blowing in opposing directions are powerful enough to tear down buildings and kill people.

“An entire bus stand levelled to nothing.” Courtesy: Rajesh Kapoor

Over the last decade, Delhi’s relationship with its troposphere has grown increasingly fraught. Every winter, a thick layer of pollution creeps over the city. The air quality deteriorates beyond measure. A privileged minority takes refuge indoors, protected by an array of air purifiers. But for the rest, the smog has become a fact of life—an occupational and residential hazard.

“A pattern will not emerge till it has maybe become irreversible. It will be 15 or 20 years before we realise what we have done.”

The fact is that the air in Delhi is insidious throughout the year. That the rest of the year seems less toxic is simply a matter of optics: the city is less visibly polluted in those months. Yet most of us can’t help but think that it’s temporary; that at some point in our lifetimes, nature will reset. What we don’t realise is that the climate isn’t changing—it has changed. Extreme weather events are our new normal.

The first official assessment, Climate Change over the Indian Region, was published by the Ministry of Earth Sciences in 2020. It estimates a temperature rise of 2.7°C by 2040 and 4.4°C by the end of the century.

The monsoon as we once knew it has ceased to exist. What lies ahead are fewer rainy days, but higher levels of rainfall and flooding. Coastal areas will have to bear the brunt of severe cyclonic activity, while the northern plains are hurtling towards land degradation and possible desertification. Delhi alone is projected to have 22 times more extremely hot days and more than 23,000 climate-related deaths annually by 2100. [6]

he streets of Delhi are usually carpeted with flowers after a March storm. The rain and the wind pluck the blooms off the amaltas and semal trees and scatter them across the city. The morning after is a sight to behold.

Writer and naturalist Pradip Krishen spoke to me fondly about Delhi’s rainy spring. He is a keen observer of the city’s natural environment—from its groundwater to the tops of its trees. It used to be a “city of cycles,” he told me in a phone interview. He recollected a time when cars found themselves stuck behind massive bicycle jams at traffic signals.

Today, it is a city of fumes and mortar. Its seasons have wholly transformed. The monsoon is shorter and more impatient. The winter frost no longer scorches the grass. The sparrows have fallen silent. A lot of it is a consequence of a diseased climate, and a weather change that—unlike a tornado—is being wrought over decades, not minutes.

Krishen explained the link between the city’s trees, the weather and its climate. A change in heat or moisture is a cue for a young tree to start flowering. Repeated signals of this kind tell the tree that it is time for cross-pollination. By the time the monsoon comes around in June, it is laden with fruit.

The technical term for this process is ‘entrainment.’ Through a process of trial and error, a tree is coached by the elements to fall in with the ways of nature. Weather patterns must repeat themselves for the tree to understand the climate. So, you can imagine a tree’s confusion when seasons mutate. A single overeager summer or lethargic monsoon can begin to chip away at a rhythm that has been achieved over ages.

That is why we may not recognise what we have lost until it’s too late. “A pattern will not emerge till it has maybe become irreversible,” Krishen told me. “It will be 15 or 20 years before we realise what we have done. Today, it will simply look like a single tree has keeled over and we will go on with our lives.”

Annika Taneja is a freelance editor, writer and translator based in New Delhi.