I

n 1947, Partition cleaved the Indian subcontinent into fragments and disputed territories: Pakistan, split between West Pakistan and East Bengal; and India in between. Villages were torn, birthplaces and graves left abandoned, territories were disputed.

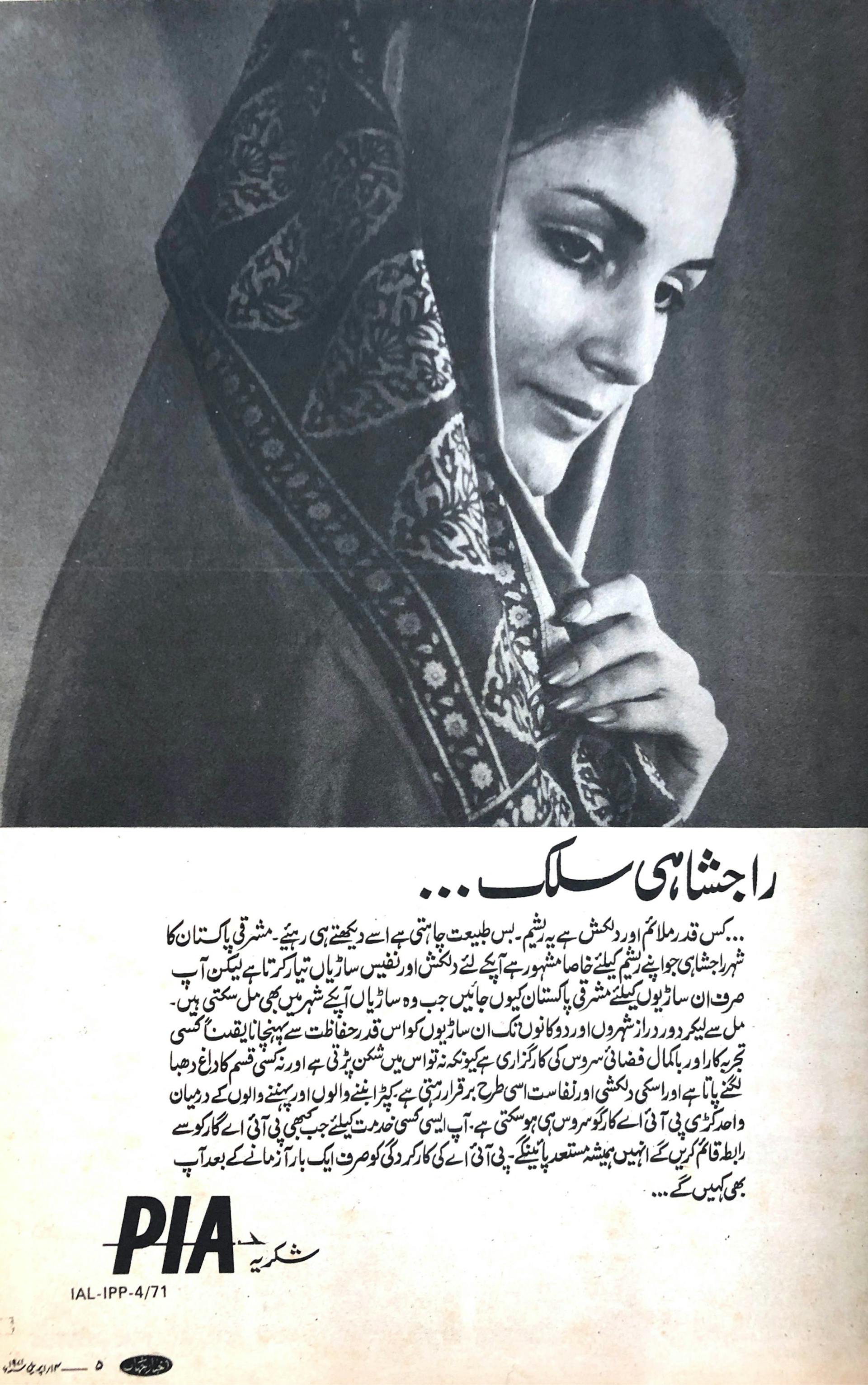

The refugees who came to West Pakistan set about rebuilding their lives in a place that was wholly unprepared and under-resourced. In Pakistan’s early years, the sari was everyday wear for Hindus and women from Bengal. Zoroastrian women in Karachi and Lahore wore saris, just as they had in undivided India. Their high-profile role in urban Pakistan’s private education system is the reason many Pakistanis associate saris with their teachers.

Daywear in West Pakistan was shalwar kameez. A 1947 photograph by the acclaimed Life photographer Margaret Bourke-White,

shows nearly everyone at a women’s work meeting in Karachi dressed in shalwar kameez and plain dupattas.

If there was one ethnic group that would become associated with the sari in West Pakistan, it was Muslim Mohajirs. The term ‘Mohajir’ loosely refers to migrants from regions like Uttar Pradesh, Madhya Pradesh, Bihar and Hyderabad. They settled in the cities of Karachi and Hyderabad in Pakistan’s Sindh province. In their trunks and memories were the garments of their previous lives: these included the gharara and the sari. Mohajir women continued to wear the sari at home, to go out shopping, and, as the country began to find its bearings, to work, at schools and in banks and at companies.

So the sari became daywear for women in Karachi, the first capital of Pakistan, and was worn without comment. “Women mostly wore saris casually—cotton saris, chiffon and georgette,” said Mohammad Azam, who runs Saree Centre in Karachi’s Bohri Bazaar. If women weren’t wearing saris, they wore ghararas, like Ra’ana Liaquat Ali Khan, the wife of the first prime minister, or Fatima Jinnah, a key society figure and the sister of Pakistan’s founder Muhammad Ali Jinnah.

In other provinces in West Pakistan, things were different. In Balochistan, the North-West Frontier Province and the tribal areas now known as Khyber Pakhtunkhwa, women wore trousers and tunics with traditional embroidery. For Punjabi Muslim refugees, saris would only have been a customary part of the trousseau—the jahez from their family’s side, or the bari, the gifts given by the groom’s family.

Punjabi women typically wore the shalwar kameez with a dupatta.

The shalwar kameez became the garment of West Pakistan. But soon after Partition, regardless of ethnic identity or familial connections, Pakistan’s new and old elite, its landowning families, and the wives of bankers and business executives, adopted the sari as formal wear. Begum Nasim Aurangzeb, the daughter of the military ruler General Ayub Khan, a Pashtun who seized power in a coup in 1958, often wore the sari on official visits abroad.

In the 1960s, upper-class families began going to photography studios for wedding and family mementoes. In these images, women are often wearing chiffon and silk saris.

Shahid Zaidi’s family founded Zaidi’s Photographers, one of Lahore’s oldest photography studios. “After Partition, there was a dull period of several years when people didn’t have enough money,” Zaidi, who is 78, told me.

“In the 1970s, a trend began. It was to take a ‘couple photo’ after the valima in a studio,” Zaidi told me. “That carried on for a good 20-25 years, that was the period when people came to the studio as a ritual, almost as a part of getting married.” The wearing of saris was very elitist, Zaidi said. But it wasn’t just for wedding portraits in a studio. People also wore saris to feel good about themselves and for specific occasions.